Unpacking the Mead–Freeman Controversy

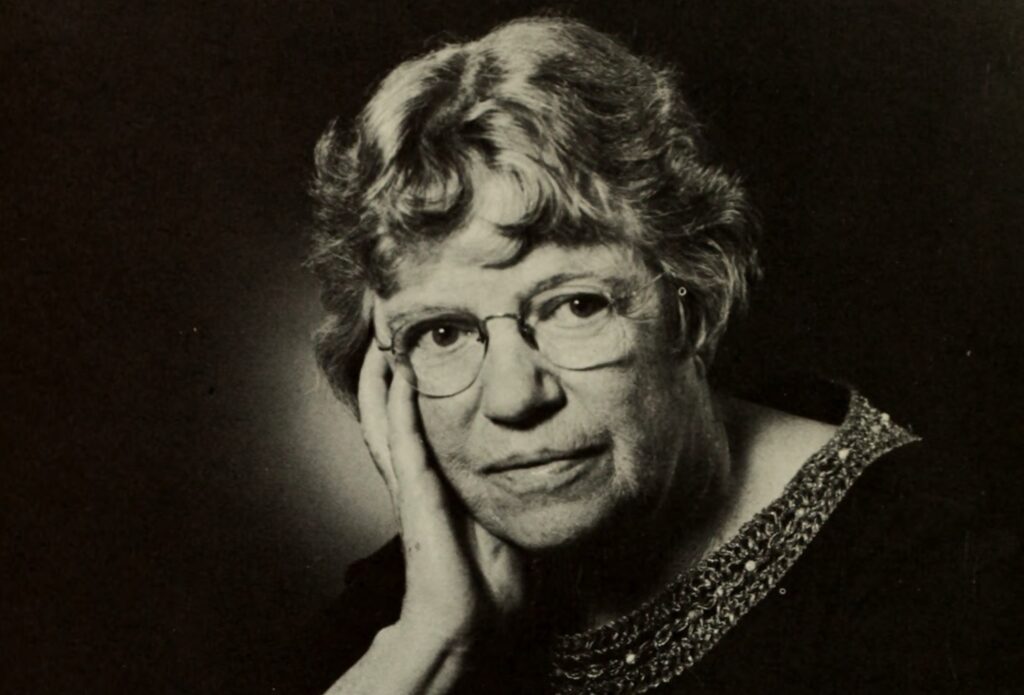

In this unit (to accompany SAPIENS podcast S6E6), students will revisit the Mead–Freeman controversy in depth, reassess how Derek Freeman critiqued Margaret Mead, and then study the consequences of the dispute within the field of anthropology. Students will apply lessons from the controversy to current research and theories.

- Summarize the timeline of the Mead–Freeman controversy.

- Review the key points of the controversy.

Could Group-Organized Violence Be Rooted in Empathy?

Compassion Sets Humans Apart

An [un]Heroic Journey

Snapshots of Losing Jenna

What Vietnam’s Scarred Lands Reveal About Modern Warfare

Why Do Swallows Fly to the Korean DMZ?

When Calls for Vengeance Go Online

A Poetics of Liberation: An Imagined Archive

The First Space Launch for Mauritius

Were Twins the Norm in Our Primate Past?

Lessons From Lucy

For Families of Missing Loved Ones, Forensic Investigations Don’t Always Bring Closure

Why I Talked to Pseudoarchaeologist Graham Hancock on Joe Rogan

Excavating the Coexistence of Neanderthals and Modern Humans

Shading U.S. Empire in Puerto Rico’s Ballroom Scene

“Stop This Invader!”—The War on Spotted Lanternflies

Fighting for Justice for the Dead—and the Living

An Order for My Backpack and Three Stages of Nowhere

Doctors Are Taught to Lie About Race

Are People Projecting Racist Stereotypes Onto Squirrels?

-

Written or spoken communication or debate.

- Derek Freeman was trained in cultural anthropology and fully immersed himself in Borneo’s Iban culture in 1940–1943. Only after studying anthropology for more than two decades did he begin to question the validity of cultural anthropology and study more biologically based subjects, such as psychology, ethology, psychoanalysis, and neuroscience, in building an interdisciplinary background and perspective to view cultures. Discuss this change in perspective.

- Before making public criticisms of Margaret Mead’s work, Freeman’s colleagues often found disagreeing with him tedious and difficult and pointed out that his “vehemence and persistence beyond a decent point of disagreement often outweighed the virtue of what he had to say” (Hempenstall, Truth’s Fool: Derek Freeman and the War Over Cultural Anthropology 2017, 116). Explore this statement with students.

- In 1964, Freeman published “Psychiatry, Anthropology and the Doctrine of Cultural Relativism.” It was the beginning of his decades-long mission to refute the emphasis anthropologists placed on the influence of culture on human behavior. He believed culture was “projections of the human animal’s impulsive phylogenetically given nature,” whereas human nature was foundational and drove culture (Hempenstall 2017, 131). Lead students in discussing this statement.

- Freeman met with Mead at the Australian National University on November 10, 1964, and attended a seminar with her the following day. Based on Freeman’s comments during the seminar, some speculate that he was caught off guard. Explore how conflicting accounts of the emotions held by Freeman and Mead worked their way into modern literature and how Mead supporters claimed she “won” by pointing to her unshaken stature and composure at this time.

- Based on his diary entries, an apology letter to Mead, and comments in a 1996 interview about meeting her, Freeman expressed respect for Mead and thought their 1964 meeting was productive. In the letter, he stated that she made some mistakes in her Samoan work, and that he planned to research her errors. Mead responded with her now well-known phrase, “Anyway, what is important is the work” (Shankman, The Trashing of Margaret Mead: Anatomy of an Anthropological Controversy 2009). Explore this exchange with students.

- Mead rose to popularity long before Freeman published his critique of her work. An anthropologist and former student of Freeman described her as “successful, optimistic, with a fervent belief in the future, [and] she reaffirmed the hope of all Americans that through education everyone could become what he or she wanted to be” (Hempenstall 2017, 194).

- In her work, Mead “acknowledged adolescent stress but argued that the lives of Samoan adolescent girls were relatively less stressful than the lives of American girls in the 1920s” (Shankman 2021, 180). She acknowledged that puberty was a universal biological experience but positioned her argument into how the process was “managed” among differing cultures. Yet Freeman labeled Mead an “absolute cultural determinist” (Shankman 2021, 176).

-

Freeman, Derek. 1966. “Social Anthropology and the Scientific Study of Human Behaviour.” Man 1 (3): 330–342.

-

Scheper-Hughes, Nancy. 1984. “The Margaret Mead Controversy: Culture, Biology, and Anthropological Inquiry.” Human Organization 43 (1): 85–93.

-

Shankman, Paul. 2000. “Culture, Biology, and Evolution: The Mead–Freeman Controversy Revisited.” Journal of Youth and Adolescence 29: 539–556.

-

Shankman, Paul. 2021. “The Mead–Freeman Controversy Continues: A Reply to Ian Jarvie.” Philosophy of the Social Sciences 48 (3): https://doi.org/10.1177/0048393117753067.

- If Freeman began to question Mead’s work after his 1943 trip to Samoa (as described by Hempenstall [2017] and in various interviews), why did he not publish his misgivings until 20 years later?

- Freeman attributes the events at Kuching in Borneo as career-altering in terms of his intellectual pursuits; it was after this, however, that colleagues and other professionals saw him in a mentally unstable light. If Kuching’s events had not occurred (or were kept quiet), would the field of anthropology have been more accepting of Freeman’s new ideas? How much does “mental stability” and how an individual expresses their ideas play a role in accepting those ideas?

- Read the SAPIENS debate articles under “Why Are Humans Violent?” Do any of the essays sway your thinking in answering the question more than the others? Why?

- Why has the Mead–Freeman controversy lasted decades, with works discussing it still published?

- New research continuously changes the way people think about the world. Take the revelation that Homo floresiensis did not light fires (see “Extinguishing the Idea That Hobbits Had Fire”). How is this change similar to the Mead–Freeman controversy? How is it different?

- Read Freeman’s New York Times obituary, by John Shaw, under Additional Resources. How did the New York Times explain Freeman’s work and his controversy with Mead? Now read a letter to the New York Times editor from Louise Lamphere, published on August 12, 2001. Discuss how the media played a role in developing and prolonging the controversy between Mead and Freeman.

- In a group setting, split the students into Mead supporters and Freeman supporters. Ask each group to present their anthropological points regarding Samoa and the controversy.

- Select a current controversial topic and citing credible sources examine both sides of the debate. Write what both sides have to say about each position. Consider if the media or advocacy groups played a role in promoting one or both sides. Is there a clear “winner”? Why or why not?

-

Article: John Shaw’s “Derek Freeman, Who Challenged Margaret Mead on Samoa, Dies at 84”

-

Book: Derek Freeman’s Margaret Mead and the Heretic

-

Video: Documentary Educational Resources’ Odyssey Series’ “Margaret Mead: Taking Note. PREVIEW”

Catherine Torres, Freedom Learning Group

The Influence of Freeman and Mead