What 2018 Taught Us About Everything Human

Throughout 2018, anthropologists have contributed to the world’s knowledge by exploring ancient caves and firepits to reveal clues about our deep history and evolution, journeying into obscure corners of the planet to study modern cultures, and analyzing the chemical makeup of our bones and the nature of human consciousness—just to name a few examples. More than this, anthropologists have done the much-needed work of exploring the complexities around climate change, gender struggles, gun violence, migration, genetics and race, and the rise of authoritarian governments. Here, SAPIENS takes a look at some of the major contributions of the field this year, from the current events that anthropologists have helped us understand more fully to the discoveries that brought new insights into what it means to be human.

First ancient-human hybrid identified

Paleogeneticists made headlines around the world when they reported the stunning find of a first-generation cross between two distinct human groups this August. The team’s analysis of a 90,000-year-old female bone from a Siberian cave showed that the individual’s mother was a Neanderthal and her father was a Denisovan (two extinct lineages of humanity). The researchers nicknamed her “Denny.” Thanks to the study of old bones and modern genomes, scientists already knew that different human groups met and mated throughout history. (Consumers can even pay to find out what percentage of their genome might be Neanderthal or Denisovan.) But finding a distinct first-generation hybrid was unprecedented and a welcome reminder of humanity’s ongoing tendency to meet, mingle, and meld rather than to live in distinct, isolated populations.

U.S. immigration put in the spotlight

U.S. President Donald Trump’s first State of the Union address this January set the stage for a troubled year of controversial immigration policies by calling for restrictions on family-based immigration and increased border security, among other things. In April, U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced a new “zero-tolerance policy” to step up criminal prosecution of people caught “illegally” crossing the border. By mid-year, troubling reports began to emerge of horrifying issues regarding detention centers, including children being separated from their families—actions sometimes supported by the inappropriate use of X-rays to determine if someone is an adult rather than a minor. Against this backdrop, the work of anthropologists aiming to document and highlight the struggle of migrants continues to put the situation in sharp relief and suggest better ways forward. One social anthropologist from Guatemala, for example, published an open letter to Trump urging him to reform U.S. foreign policies and support anti-corruption efforts, which would help to stem the migration tide and spread wealth in Central America.

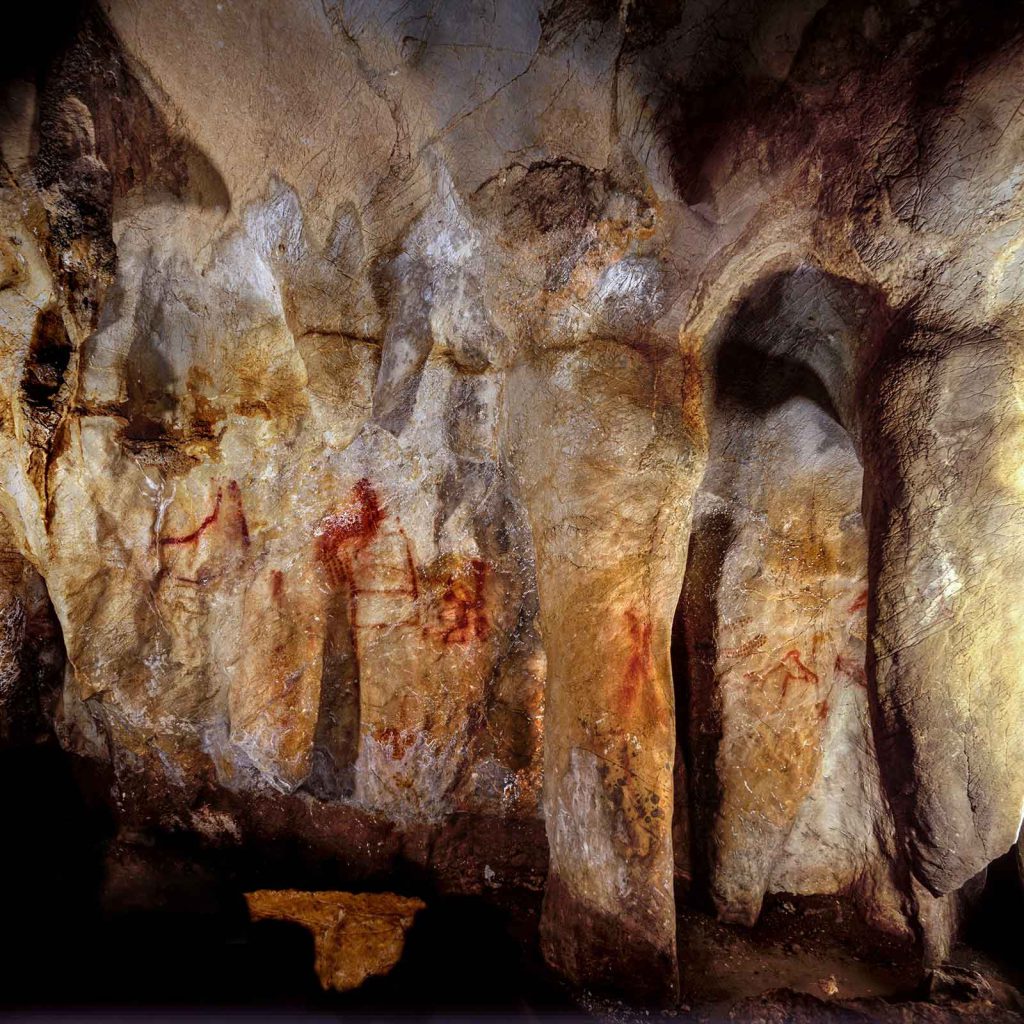

Oldest art found … twice

In February, researchers reported cave paintings—ladder-like patterns, dots, and handprints—in Spain that date to more than 65,000 years old. That makes them about 25,000 years older than the previously oldest-known cave paintings and means they were made by Neanderthals long before Homo sapiens even arrived in Europe. Then, in September, researchers reported some 73,000-year-old crosshatching marks found on a rock in Blombos Cave in South Africa—a new contender for the oldest drawings by Homo sapiens. The entire concept of art, of course, is much older yet—researchers have found abstract engravings on shells going back hundreds of thousands of years. The tracing of art’s evolution helps us to better understand the core nature of humanity and helps to chip away at the old stereotype that Neanderthals were dim-witted and artless.

Alternative consciousness explored

In October, Canada became the latest country to legalize marijuana for recreational use and sale (only Uruguay before them had similarly liberal rules on the drug). Anthropologists have played a vital role in Westerners’ ongoing explorations with consciousness-altering drugs, from psychoactive marijuana to mushrooms, peyote, and ayahuasca. American anthropologist Michael Harner, for one, who passed away this February, founded the Foundation for Shamanic Studies in part after his own experiences with hallucinogens in South America. He is widely credited with bringing shamanism to Westerners, teaching practitioners to change their state of consciousness at will, without drugs. As the new science of psychedelics and hallucinogens grows, and more U.S. states legalize the use of marijuana, anthropologists will continue to help navigate the space between “policies of prohibition and new subcultures of psycho-spiritual therapy,” as panelists at the recent American Anthropological Association meeting put it.

Yet more Pompeii artifacts uncovered

The remains of the ancient city of Pompeii were first found by a surveying engineer 270 years ago; since then the site has become a massive tourist destination, subject to intense archaeological exploration. Yet even after hundreds of years, the eerily preserved remnants of the Roman city, enshrined in ash by Mount Vesuvius’ eruption in A.D. 79, keep on giving. In 2018, the site’s overseers opened up one section, left dormant for decades, for further excavation. This has yielded new plasters and frescoes unadulterated by earlier restoration efforts, a skeleton dramatically pinned beneath a rock, and a dated charcoal inscription suggesting that the eruption happened months later than once thought. Other excavations on the outskirts of the city also revealed the remarkable full remains of a horse. The site seems destined to reveal yet more surprises and treasures for years to come.

Oldest bread crumbs swept up

The toasty crumbs of a flatbread baked some 14,500 years ago were found in the remains of a stone fireplace in Jordan. Researchers had previously seen evidence for flour-making, but most would have put the beginnings of bread somewhere around 11,500 years ago in the fertile crescent (stretching from the Nile Valley to Mesopotamia). The new find—a multigrain bread made with wild barley, einkorn, oats, and tubers—shows that people began making bread thousands of years before the development of agriculture. Perhaps a love of bread was the thing that drove people to cultivate flour-making crops, the researchers speculate. Deconstructing ancient peoples’ menus helps to reveal the details of this critical step in human history.

Clovis child’s birthday revised

A mystery surrounding one of the most famous skeletons in North America—an infant boy found on a private Montana ranch some 50 years ago—was put to rest this year. The child, dubbed Anzick-1 by archaeologists, was long thought to be a part of the early Indigenous tradition in the Americas known as Clovis. Anzick-1 was found in a gravesite along with ochre-stained stone tools and antlers dating to about 13,000 years ago—the right timeframe for a Clovis site. But carbon-dating tests of Anzick-1 himself have come out much, much younger—perhaps thousands of years more recent than the surrounding artifacts.

This year, researchers re-tested the bones with a different method less prone to contamination. The result: The boy belonged to the Clovis era. The resolution supports the idea that the first Americans came from Siberia: Anzick-1’s genome has been sequenced, showing that he was a close relation of both early Siberian populations and modern Central and South American groups. But the tangled history of how and where modern humans arose, and how they eventually spread to the Americas is still an ongoing debate.

Tribal remains like those of Anzick-1 have also raised questions for many researchers about how best to work in collaboration with Indigenous peoples and other stakeholders: Various researchers spent years attempting to locate and talk with the appropriate tribes to discuss how the boy’s bones should be (and had been) studied, but there was no clear consensus. The idea of coproducing knowledge with scientists, Indigenous groups, and other stakeholders acting as partners remained a hot area of discussion and a source of controversy in 2018.

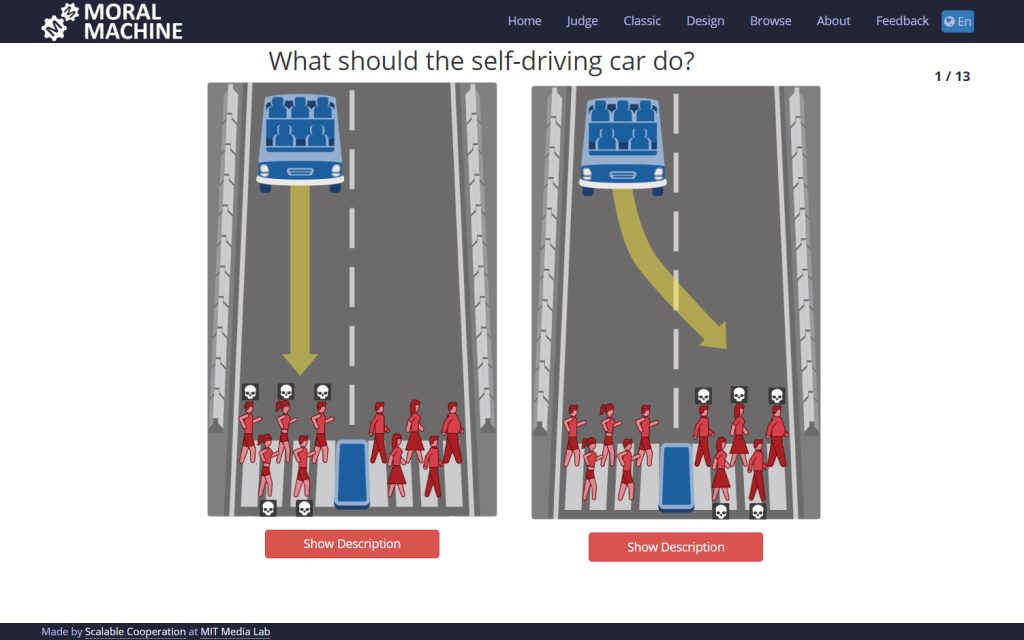

The Moral Machine data crunched

A global survey of 2.3 million people published this October revealed fascinating differences in the ethical decision-making of people from more than 130 countries. The Moral Machine project, hosted by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Boston, aims to gather a “human perspective on moral decisions made by machine intelligence, such as self-driving cars.” The effort is designed to help inform programming when future machines encounter ethically fraught moments—like whether a car should swerve to avoid killing a pedestrian, even if that results in the death of the car’s driver. How do you weigh one life against another? Do you make decisions based on which action will likely kill the fewest people, the oldest, or the poorest? Is it better to kill through inaction, by not turning the wheel, than through action, such as intentionally steering into someone? Does a machine have an ethical duty to specifically protect its owner? (Visitors to the website can play around with some scenarios for themselves and contribute to the project.)

The work, informed by anthropologists, economists, psychologists, and computer scientists, revealed that people from countries with strong governing institutions, such as Japan, were more likely to choose to hit people acting illegally, like jaywalkers. Those from countries with a bigger gap between rich and poor, like Colombia, were more likely to choose to hit people with lower social status, like a homeless person. Though the scenarios were stark, and the results of virtual games might not reflect people’s decisions in reality, the main point stands: Morality is culturally flexible.

Brazil’s treasures burned

In September, a tragic fire gutted the largest natural history museum in Latin America. The flames took with them irreplaceable treasures, including an estimated 20 million artifacts. Among them were the only known audio recordings of now-extinct Indigenous languages, the 200-year-old palatial building itself, and the paperwork of untold ongoing research projects. Of course, this is not the first time that historic objects have been lost—valuables have been taken by flames, theft, war, and even climate change in other parts of the world. But Brazil’s tragedy was a stark reminder of the urgent need to invest in record-keeping. Brazil’s National Museum had been starved of funding and care; it had termites and reportedly no sprinkler system to protect it.

It is still unclear how much has been saved and what will happen next. There are ongoing efforts to collect digital scans or photographs that visiting international researchers or tourists took at the museum in the past. But the recent election of far-right Jair Bolsonaro as president in Brazil has left little hope that a new museum, or science, will receive funding priority.

Ebola outbreak tackled

As the year comes to a close, an outbreak of the deadly Ebola virus in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) has become the second largest in history, with more than 500 people diagnosed and 289 deaths (and counting). Although that’s still far from the 2013–2016 tragic body count of more than 11,000 people in West Africa, the outbreak has experts concerned and scrambling for solutions. Health workers know that both vaccination and communication efforts are imperative—in May, at the very start of the current outbreak, the Africa Centres for Disease Control sent anthropologists into the DRC to help with their efforts there. An Ebola Response Anthropology Platform compiled useful information from previous outbreaks about how, for example, to best contain the risk of disease transmission during traditional burial practices. Surveys in Sierra Leone and Cameroon both showed that a ban on hunting, selling, and eating so-called “bushmeat” during the 2013–2016 crisis did little more than create a climate of mistrust of officials, eroding public faith in all disease-prevention messages. Understanding how people respond to disease outbreaks, and the rules and regulations designed to minimize them, will be essential to preventing future tragedies.