Tackling the Impossibility—and Necessity—of Counting the World’s Languages

As a scientist who has researched language diversity for a decade and a half, I recently joined a team to work on a task that even some linguists think is “ultimately unobtainable”: helping catalog and count the world’s complex and ever-changing languages. I am part of an international team of experts assembled by UNESCO to create a World Atlas of Languages. This catalog will hopefully generate updated estimates of the number of active languages and information on how these languages are being used.

Typically, when I present research, one of my gimmicks is to begin with a rough estimate of the number of natural languages in use today: between 7,000 and 8,000. My point is to communicate that there are many languages and, therefore, an incredible diversity of ways humans think, reason, and feel. But pinpointing a more precise number opens the door to all sorts of problems.

For example, the Central African Republic hosts about 70 languages. The speakers of many of these languages live deep within roadless rainforests in villages that are very difficult for government representatives and other researchers to access. It’s hard to fathom how resource-intensive it would be to form an accurate linguistic picture of this country alone.

Of course, our project is far from the first to attempt to categorize and quantify languages. Many groups and individuals have done this in the past and continue to do so.

My task set me on a path to understanding the history and craft of counting languages. While I expected to read a dull sequence of estimates, I instead found a riveting tale involving Christian missionaries, post-war idealists, a colonialist opium agent, and more. I also gained even more appreciation for the potentially impossible task of counting languages.

WHY COUNT LANGUAGES?

Every year, roughly three languages cease to have active users. This leads to negative outcomes for communities, including the loss of unique cultural knowledge. As linguist Kenneth Hale put it, losing a language is “like dropping a bomb on the Louvre.”

Researchers, institutions, and governments need to document the number of languages to develop and assess policies aimed at enhancing the vitality of dwindling languages. They also need to translate information to ensure as many people as possible can access various resources. Therefore, they need an accurate picture of the number and location of languages in a region.

In addition, scientists use language statistics to understand why languages and cultures are distributed the way they are across the globe. Their insights have revealed a number of intriguing parallels between biological and cultural diversity. For example, languages seem to follow Rapoport’s rule, which in ecology states that plants’ and animals’ geographic range grows the farther you go from the equator. Similarly, the farther from the equator a language is, the wider the spatial range of its users.

Studying linguistic diversity also offers insights into the way languages influence cognition. By extension, this research shows how the broader understanding of fields such as science, medicine, and technology are limited and biased due to the almost exclusive monopoly of a few languages that dominate these arenas.

THE CHALLENGES OF COUNTING LANGUAGES

To define a system of communication as a distinct language—as opposed to a dialect or variety of a language—it must be sufficiently unintelligible from other languages. Sometimes the boundaries between languages are clear-cut; other times, they are blurrier.

For example, there are differences in the accent, vocabulary, and grammar of English spoken in Chicago, Belize City, Glasgow, Mumbai, Nairobi, and Cape Town. Yet these are typically labeled as varieties of English because, presumably, their speakers can manage to understand one another. But caveats apply. There are times when two native English speakers from different countries can struggle to comprehend each other.

A commonly brought up rule is that if speakers of two different communication systems can understand 70 percent or more of what each other is saying, they are speaking two varieties of a language rather than two separate languages. But even this gets convoluted.

Take, for example, the 1986 Men’s FIFA World Cup in Mexico, which featured the most amazing goal in the history of football (or “soccer,” depending on which variety of English you speak). Some Brazilian TV channels dubbed the games in Portuguese. Others left the interviews with players and the official communications in their original Spanish.

Researchers have estimated that Brazilian Portuguese speakers comprehend around 60 percent of Spanish. But that figure was based on university students’ comprehension of texts that covered a meager number of literary genres and varieties of Spanish. It’s easy to imagine scenarios in which that percentage would drop to almost zero—for example, if a nonspecialist Portuguese speaker listened to someone reading a paper on string theory in Spanish.

By contrast, communication in sports tends to be stereotypical (“we played a good game,” “the other team was tough”) and supported by visual cues that convey meaning. One might presume, then, that many Brazilians watching the 1986 World Cup in Spanish understood well over 70 percent of the broadcast. This example illustrates the complications of using a single number to estimate intelligibility.

Politics also comes into play when asking communities or countries to codify languages. Given sufficient political will, two highly mutually intelligible languages can be treated as separate entities across national and state borders. Textbook examples include Indonesian and Standard Malay, Dari and Persian, and Bosnian-Croatian-Montenegrin-Serbian, which lost its hyphens after the Balkan War in the 1990s, giving rise to two to four languages, depending on who you ask.

Conversely, some forms of spoken Chinese, including Mandarin and Yue, are not mutually intelligible. But they are often regarded as variants or dialects of Chinese rather than different languages due to China’s relatively strong sense of ethnolinguistic identity, common cultural heritage, and widely understood written system.

Asking individuals about language distinctions is also delicate because of differing notions of what counts as a language, who should speak which language, and other ethical considerations. There are plenty of recorded instances of people denying they know a language, then speaking it fluently with their peers under the puzzled gaze of a linguist.

The opposite also happens. In French Polynesia, Pierrot Faraire is considered the main living authority on the Rapa language, which was displaced by Tahitian and French. But elders’ testimony and documentary evidence suggest his Rapa is mostly a new concoction.

These are just skin-deep descriptions of some of the issues with counting languages. But the message is clear: Delineating languages is not merely a scientific or technical exercise, and there is ample room for opinion and bias. So, claiming to know how many languages exist with precision can be considered an act of extraordinary scholarship—or folly. Or both. But that hasn’t stopped people from trying.

COUNTING LANGUAGES FOR COLONIALISTS AND WATCH COMPANIES

Leaving aside a handful of early documented attempts to describe the world’s known languages, the first resource-intensive initiatives to count and map languages were commissioned in the late 1800s and early 1900s for the explicit purpose of colonial administration.

Perhaps the best-known example is the Linguistic Survey of India, which involved a colossal network of government officials around the country. The survey’s main mastermind, Sir George Abraham Grierson, was one of the British Empire’s opium agents in India. (He was also a linguist, although this is a much less surprising fact about him.) He expected the deed to take three years. The survey actually took close to 30, and it was not without shortcomings.

The first large-scale effort to conventionalize language names worldwide dates to the post–World War II era. In 1947, the International Organization of Standardization was founded with the intention of concocting globally applicable standards in engineering, measurement, and beyond. This became particularly pressing amid impending Americanization and efforts to regenerate international trade. The democratic and egalitarian nature of this organization was enshrined in its short name: ISO. While it might appear to be an acronym, it actually combines the first letters of the institution while recalling the Greek word for “equal,” isos.

In 1967, the organization completed the ISO 639. Its goal was to streamline communication between international experts in science and technology. So, it was less concerned with celebrating the planet’s linguistic diversity than it was with creating convenient one- to two-letter labels for languages (such as E for English, F for French, and Zu for Zulu) that could be used, for example, in documents at conferences. The ISO 639 provides the following hypothetical situation to explain why their language labels could be useful:

A well-known watch factory encloses with its five-language catalog an introduction in only one of the five languages, according to the request of the addressee. These interchangeable introductions are held together by tapes which are only marked by one of the five letters E, F, D, I, or S.

Picking a “well-known watch factory” as a main example is much less mystifying when you take into account that these ISO meetings took place in Geneva, Switzerland.

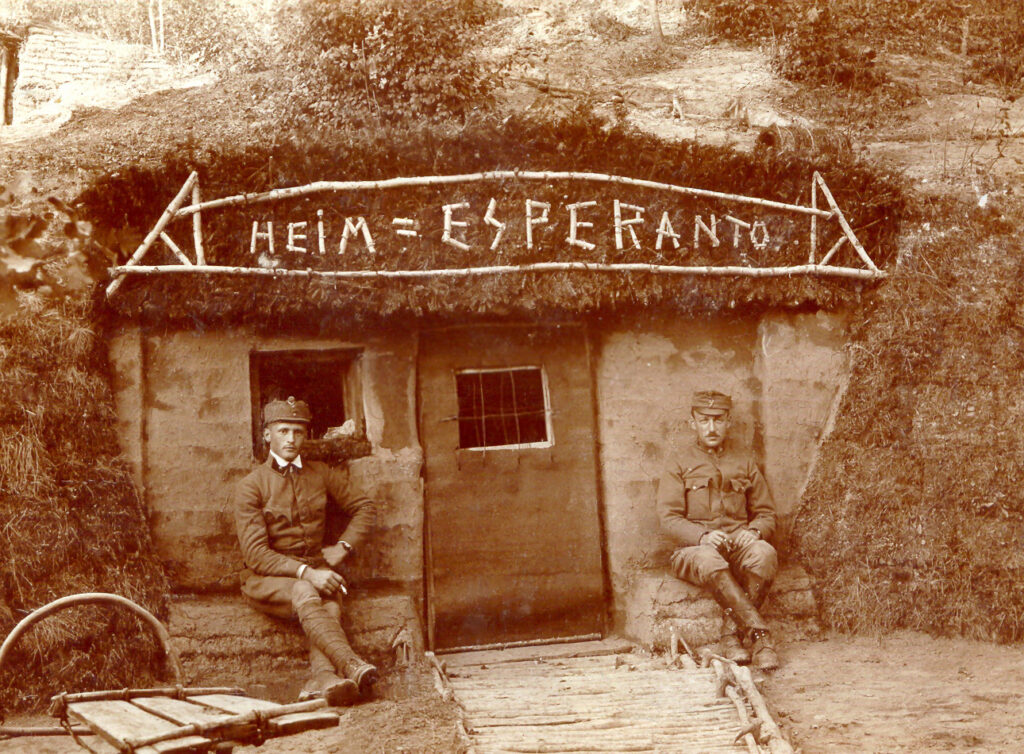

The ISO created labels for 183 languages. Perhaps the most striking inclusions are the constructed languages Esperanto, Volapük, Interlingua, and Ido. Back then—when the gigantic human loss brought by WWII was fresh in people’s minds—the idea that humans needed to establish a shared language made more sense than it does today, when English has fought its way (sometimes literally) to the top as the world’s lingua franca.

Fast forward to 2007, when the ISO 639-3 documented more than 7,500 languages, including ancient languages and languages that have no current users. To compile this catalog, ISO joined forces with an independent effort to name and count the world’s languages: Ethnologue, which has its own peculiar history.

SPREADING THE GOSPEL IN ALL LANGUAGES

Ethnologue’s story begins with a missionary: William Cameron Townsend.

In 1918, Townsend was spreading the gospel in the Guatemalan highlands. The institution he served had outlined a plan in Spanish. But the region’s Indigenous peoples spoke many other languages. Townsend became attached to the Kaqchikel people, learned their language, and after 14 years, finished the first translation of the New Testament in Kaqchikel.

During the process, he founded Camp Wycliffe, named after one of the first translators of the Bible into English. The camp gave young missionaries a crash course in linguistic documentation. Shortly after, Townsend abandoned most of the religious symbols and historical baggage, rebranding the organization’s efforts in the light of scientific and humanitarian causes.

This strategy allowed Townsend, and those who followed his footsteps, to gain access to places and languages that would have been impenetrable to traditional Christian missionaries. As part of this endeavor, he rechristened Camp Wycliffe the Summer Institute of Linguistics (SIL), a name devoid of Christian connotations. Now known as SIL International, this institution runs Ethnologue.

For the last couple of decades, Ethnologue has been the de facto main reference for naming and counting languages, determining the number of speakers of each language, and (controversially) assessing languages’ vitality status. They are not shy to say so. In its 25th online version, Ethnologue claims to be “the most authoritative resource on world languages, trusted by academics and Fortune 500 companies alike.” I do not claim to have any insights into advertising strategies, but I presume it’s compelling to know you are tapping into the same linguistic knowledge pool as John Deere and Foot Locker.

Linguists also rely on SIL for their research, such as finding reliable contacts in the communities they’re studying or obtaining relevant software for their fieldwork. However, the main mission of SIL International is still to translate the Bible. This task might sometimes be at odds with the preservation of linguistic diversity. Spreading the Bible emphasizes reading over the Oral Traditions that are essential to some communities. And translating the Bible into a particular language variety in a region might endow it with extra prestige, to the detriment of other languages.

THE FUTURE OF COUNTING LANGUAGES

At the moment, there are few true alternatives to Ethnologue. Perhaps the best known is Glottolog. This online database is free, thanks to the department of cultural and linguistic evolution at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany. It claims to be a “comprehensive catalog,” and it promises that “any variety that a linguist works on should eventually get its own entry.”

“Eventually” does a lot of work here. Glottolog is run by a few linguists who curate the site out of passion. This feat deserves praise, but it’s not the most sustainable solution. Glottolog’s decisions about what counts as a language and how languages are related to one another is based on the “best guess by the Glottolog editors.” There is no public paper trail outlining how each decision was reached, but the site acknowledges that more than 250 people “provided confirming and/or clarificatory information.”

It is unclear what would happen if Glottolog’s editors were unable to continue this work. That’s perennially a concern given the paucity of funding for such endeavors.

Given all the technical, conceptual, ethical, and financial challenges involved in creating language catalogs, it is not surprising that some believe the endeavor is ultimately pointless. In a 2013 conference, linguists Stephen Morey and Mark Post argued that attempts to standardize linguistic diversity were “doomed” given the dynamic nature of languages: They just don’t behave the way we wish they would.

I am not entirely unsympathetic to the feeling expressed here. But I wonder what our collective understanding of linguistic diversity would be without these faulty and limited catalogs.

How would we know that New Guinea’s population of over 12 million speaks more than 800 languages, while Europe’s estimated 750 million people speak only about 200? How else would we have reconstructed the cultural history of entire human lineages and fragments of ancient vocabularies? And how can we track and potentially reverse language loss around the globe except by continuing to count languages, even if they don’t behave the way we want them to?