Huh? The Valuable Role of Interjections

This article was originally published at Knowable Magazine and has been republished under Creative Commons.

LISTEN CAREFULLY TO a spoken conversation and you’ll notice that the speakers use a lot of little quasi-words—“mm-hmm,” “um,” “huh?,” and the like—that don’t convey any information about the topic of the conversation itself. For many decades, linguists regarded such utterances as largely irrelevant noise, the flotsam and jetsam that accumulate on the margins of language when speakers aren’t as articulate as they’d like to be.

But these little words may be much more important than that. A few linguists now think that far from being detritus, they may be crucial traffic signals to regulate the flow of conversation as well as tools to negotiate mutual understanding. That puts them at the heart of language itself—and they may be the hardest part of language for artificial intelligence to master.

“Here is this phenomenon that lives right under our nose, that we barely noticed,” says Mark Dingemanse, a linguist at Radboud University in the Netherlands, “that turns out to upend our ideas of what makes complex language even possible in the first place.”

For most of the history of linguistics, scholars have tended to focus on written language, in large part because that’s what they had records of. But once recordings of conversation became available, they could begin to analyze spoken language the same way as writing.

When they did, they observed that interjections—that is, short utterances of just a word or two that are not part of a larger sentence—were ubiquitous in everyday speech. “One in every seven utterances are one of these things,” says Dingemanse, who explores the use of interjections in the 2024 Annual Review of Linguistics. “You’re going to find one of those little guys flying by every 12 seconds. Apparently, we need them.”

Many of these interjections serve to regulate the flow of conversation. “Think of it as a tool kit for conducting interactions,” says Dingemanse. “If you want to have streamlined conversations, these are the tools you need.” An “um” or “uh” from the speaker, for example, signals that they’re about to pause but aren’t finished speaking. A quick “huh?” or “what?” from the listener, on the other hand, can signal a failure of communication that the speaker needs to repair.

That need seems to be universal: In a survey of 31 languages around the world, Dingemanse and his colleagues found that all of them used a short, neutral syllable similar to “huh?” as a repair signal, probably because it’s quick to produce. “In that moment of difficulty, you’re going to need the simplest possible question word, and that’s what ‘huh?’ is,” says Dingemanse. “We think all societies will stumble on this, for the same reason.”

Other interjections serve as what some linguists call “continuers,” such as “mm-hmm”—signals from the listener that they’re paying attention, and the speaker should keep going. Once again, the form of the word is well suited to its function: Because “mm-hmm” is made with a closed mouth, it’s clear that the signaler does not intend to speak.

Sign languages often handle continuers differently, but then again, two people signing at the same time can be less disruptive than two people speaking, says Carl Börstell, a linguist at the University of Bergen in Norway. In Swedish Sign Language, for example, listeners often sign “yes” as a continuer for long stretches, but to keep this continuer unobtrusive, the sender tends to hold their hands lower than usual.

Different interjections can send slightly different signals. Consider, for example, one person describing to another how to build a piece of IKEA furniture, says Allison Nguyen, a psycholinguist at Illinois State University. In such a conversation, “mm-hmm” might indicate that the speaker should continue explaining the current step, while “yeah” or “OK” would imply that the listener is done with that step and it’s time to move on to the next.

WOW! THERE’S MORE!

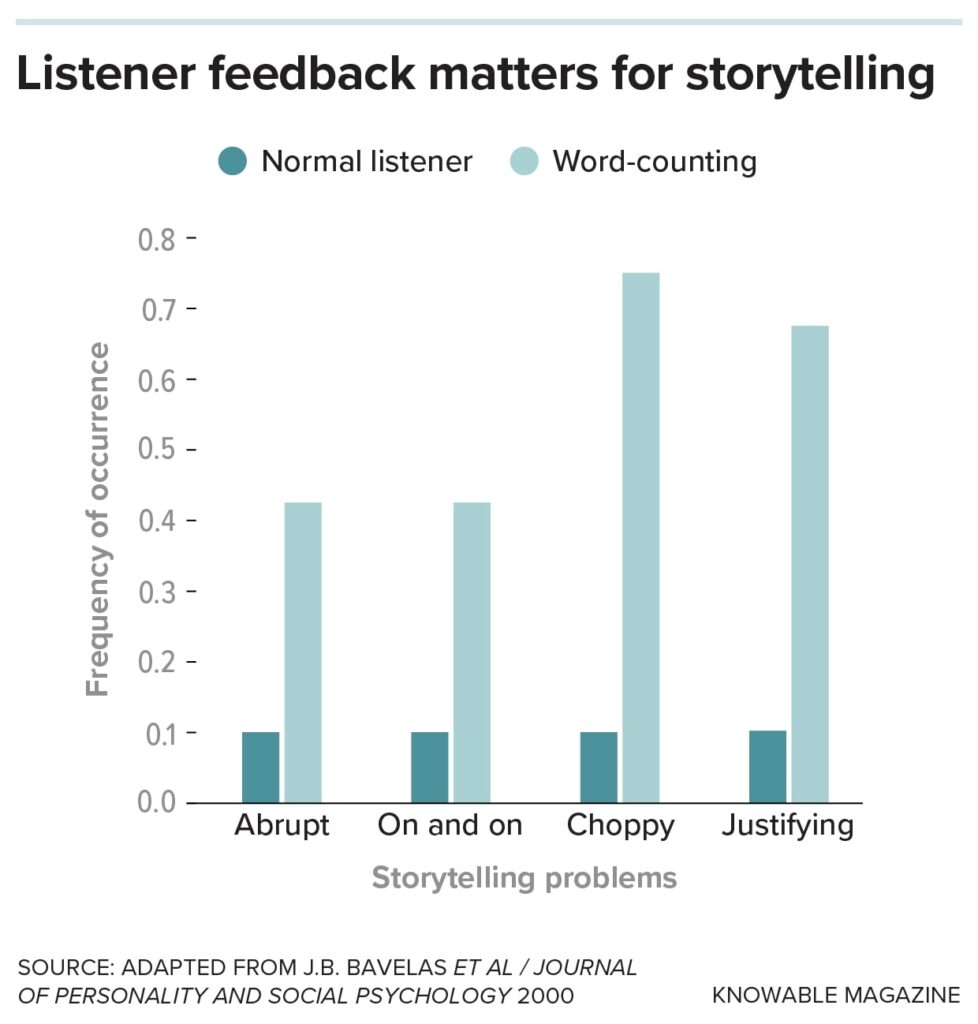

Continuers aren’t merely for politeness—they really matter to a conversation, says Dingemanse. In one classic experiment from more than two decades ago, 34 undergraduate students listened as another volunteer told them a story. Some of the listeners gave the usual “I’m listening” signals, while others—who had been instructed to count the number of words beginning with the letter “t”—were too distracted to do so. The lack of normal signals from the listeners led to stories that were less well crafted, the researchers found. “That shows that these little words are quite consequential,” says Dingemanse.

Nguyen agrees that such words are far from meaningless. “They really do a lot for mutual understanding and mutual conversation,” she says. She’s now working to see if emojis serve similar functions in text conversations.

The role of interjections goes even deeper than regulating the flow of conversation. Interjections also help in negotiating the ground rules of a conversation. Every time two people converse, they need to establish an understanding of where each is coming from: what each participant knows to begin with, what they think the other person knows, and how much detail they want to hear. Much of this work—what linguists call “grounding”—is carried out by interjections.

“If I’m telling you a story and you say something like ‘Wow!’ I might find that encouraging and add more detail,” says Nguyen. “But if you do something like, ‘Uh-huh,’ I’m going to assume you aren’t interested in more detail.”

A key part of grounding is working out what each participant thinks about the other’s knowledge, says Martina Wiltschko, a theoretical linguist at the Catalan Institution for Research and Advanced Studies in Barcelona, Spain. Some languages, like Mandarin, explicitly differentiate between “I’m telling you something you didn’t know” and “I’m telling you something that I think you knew already.” In English, that task falls largely on interjections.

One of Wiltschko’s favorite examples is the Canadian “eh?” “If I tell you you have a new dog, I’m usually not telling you stuff you don’t know, so it’s weird for me to tell you,” she says. But “You have a new dog, eh?” eliminates the weirdness by flagging the statement as news to the speaker, not the listener.

Other interjections can indicate that the speaker knows they’re not giving the other participant what they sought. “If you ask me, ‘What’s the weather like in Barcelona?’ I can say, ‘Well, I haven’t been outside yet,’” says Wiltschko. The well is an acknowledgment that she’s not quite answering the question.

Wiltschko and her students have now examined more than 20 languages, and every one of them uses little words for negotiations like these. “I haven’t found a language that doesn’t do these three general things: what I know, what I think you know, and turn-taking,” she says. They are key to regulating conversations, she adds: “We are building common ground, and we are taking turns.”

Details like these aren’t just arcana for linguists to obsess over. Using interjections properly is a key part of sounding fluent in speaking a second language, notes Wiltschko, but language teachers often ignore them. “When it comes to language teaching, you get points deducted for using ums and uhs because you’re ‘not fluent,’” she says. “But native speakers use them because it helps! They should be taught.” Artificial intelligence, too, can struggle to use interjections well, she notes, making them the best way to distinguish between a computer and a real human.

And interjections also provide a window into interpersonal relationships. “These little markers say so much about what you think,” she says—and they’re harder to control than the actual content. Maybe couples’ therapists, for example, would find that interjections afford useful insights into how their clients regard one another and how they negotiate power in a conversation. The interjection “oh” often signals confrontation, she says, as in the difference between “Do you want to go out for dinner?” and “Oh, so now you want to go out for dinner?”

Indeed, these little words go right to the heart of language and what it is for. “Language exists because we need to interact with one another,” says Börstell. “For me, that’s the main reason for language being so successful.”

Dingemanse goes one step further. Interjections, he says, don’t just facilitate our conversations. In negotiating points of view and grounding, they’re also how language talks about talking.

“With ‘huh?’ you say not just ‘I didn’t understand,’” says Dingemanse. “It’s ‘I understand you’re trying to tell me something, but I didn’t get it.’” That reflexivity enables more sophisticated speech and thought. Indeed, he says, “I don’t think we would have complex language if it were not for these simple words.”

CAN AI LEARN TO USE INTERJECTIONS?

To make artificial intelligence sound more natural, developers are building interjections into its responses. Google’s NotebookLM, for example, offers the option of summarizing information—say, one or more scientific papers—in the form of a podcast hosted by two AI-generated hosts.

On first hearing, the program does a pretty good job: The hosts joke, laugh, and insert “mm-hmm” and “wow!” at superficially appropriate times. But to the ears of a trained linguist, there’s something amiss. (Listen to an example.)

“They almost work but not quite,” says theoretical linguist Martina Wiltschko of the Catalan Institution for Research and Advanced Studies. “They kind of remind me of AI art, where there’s too many fingers. You don’t see it at first, but if you look carefully, you see that something’s wrong.”

One tell is that when the listener mm-hmms or laughs, the speaker pauses while they do so, lending a slightly creepy note to the simulated conversation. “To me, it’s almost like the uncanny valley,” says Wiltschko. “It’s close, but it’s not quite close enough.”

The biggest deficiency, though, is a robust sense of who knows what in the conversation. The AI hosts seem to flip back and forth on which one knows which pieces of information.

“It’s not just what they’re saying, it’s who’s talking in what context, and who knows what,” says Wiltschko. “I would be really surprised if the AI could ever handle that—and human beings handle that with ease.”