How to Resurrect Dying Languages

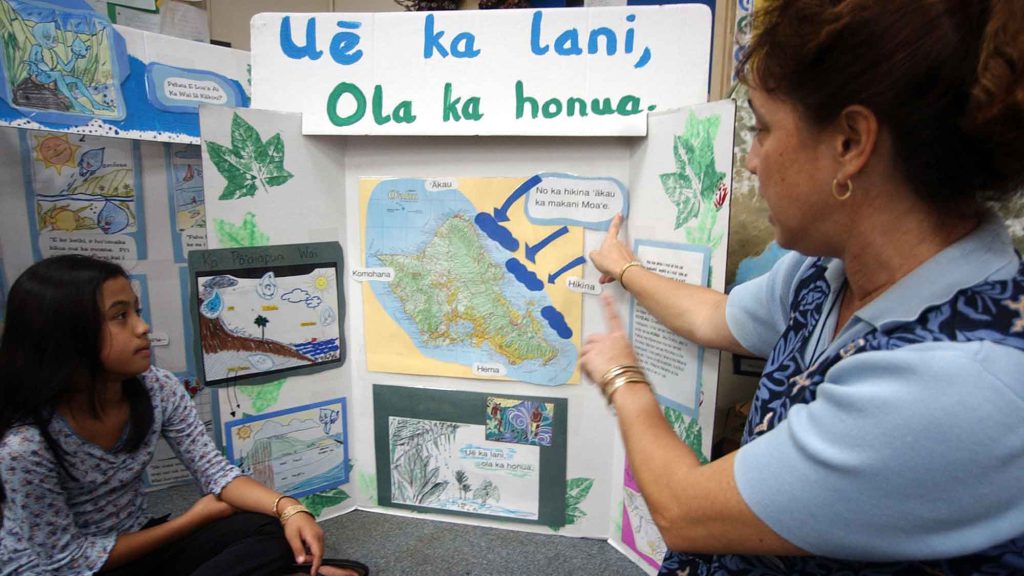

In the 1970s, the Hawaiian language seemed poised for extinction. Only about 2,000 native speakers remained, and most were over age 60. Then a dedicated group of advocates launched immersion schools, a Hawaiian radio program, and an island-wide movement to resuscitate the melodious language. Today more than 18,600 people speak Hawaiian as fluently as they speak English.

Around the world, other Indigenous languages are experiencing revivals. More and more children are being raised as native speakers of Euskara in Spain, Māori in New Zealand, and Quechua in Peru and Bolivia. Activists are making street signs, public maps, news programs, films, publications, websites, and music available in various heritage languages.

Some people are even resurrecting “extinct” languages. In southwest England, Cornish—whose last native speaker died in 1777—was taken off UNESCO’s list of extinct languages in 2010 and is enjoying a small but proud reawakening, thanks in part to the internet.

We live in a pivotal time for language revitalization. More than half the world’s languages are in danger of being swallowed up by dominant languages within this century. In November, the United Nations—which named 2019 the International Year of Indigenous Languages—approved a draft resolution declaring 2022–2032 the International Decade of Indigenous Languages.

A growing movement of language activists, cultural stakeholders, and scholars are finding new ways to foster generations of speakers through everything from digital dictionaries to drum circles. These programs are elevating the status of heritage languages in the public eye, providing opportunities for people to connect, and helping marginalized communities address longstanding discrimination.

But turning the tide of language extinction is no easy feat, and many languages being revived are still considered threatened.

As a linguistic anthropologist and program director for the Living Tongues Institute for Endangered Languages in Salem, Oregon, I have conducted fieldwork in the Americas and Pacific Islands, and spoken to language activists around the world about their successes and setbacks. Which strategies for revitalizing languages work? What hurdles are communities facing? And what creative solutions are groups using to nurture threatened languages or to bring dormant ones back to life?

“We know that to keep languages alive, you have to create a robust immersive environment,” says Philippe Tsaronsere Meilleur, executive director of Native Montreal, an Indigenous learning center in Canada. Many anthropologists and linguists agree that total immersion offers the best path toward fluency, though each community has different needs, and language revitalization goals are best steered by local stakeholders.

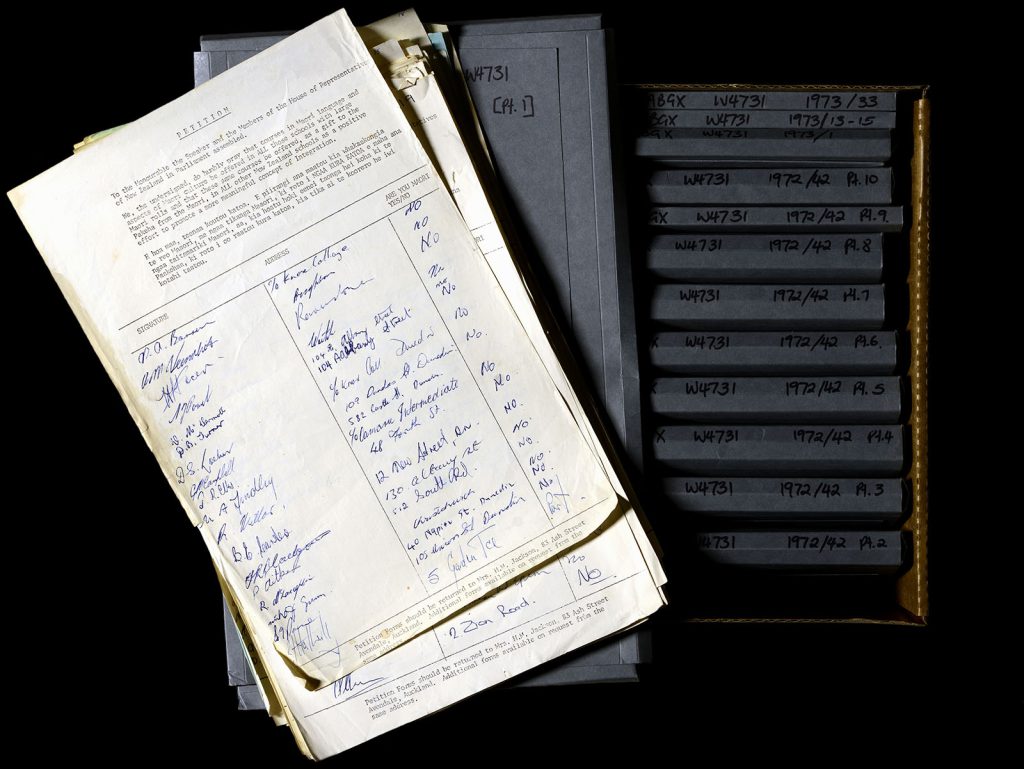

The immersion method is exemplified by “language nests,” where toddlers and other beginners learn from fluent or semi-fluent elders on a regular basis. One of the first language nests was started in New Zealand in 1982 by Māori elders who worried that their language, culture, and even pride were disappearing. The elders decided to teach children their native tongue through culturally relevant song and play, “like a bird looking after its chicks,” as Māoris say—hence the term “language nest.”

The language nest model was so successful it migrated to Hawaii and then throughout the world. Language nests are typically physical spaces but can also be found online, such as this Cherokee version.

Language nests and other community-based approaches encourage parents to embrace speaking their heritage language(s) at home. But to involve parents, programs must be adaptable. “If you are a single mom and trying to learn your Native language, we have to be accessible for [you],” Meilleur says. “We need child care. We need flexible schedules for parents and weekend schedules. The location and timing of our courses are really important for our success.”

While immersion programs can have excellent outcomes, they require significant funding and resources to remain sustainable over time. “The lack of capacity makes it hard: not enough content, training, and teachers,” Meilleur says. “People don’t realize the cost of revitalizing languages and what it would cost to run entire educational systems in these languages. To establish the institutions, to train the people, [and to] make sure the proper techniques are in place to write and read in our languages is a huge challenge.”

That’s especially true in regions where numerous Indigenous languages are spoken. At Native Montreal, for example, instructors teach languages such as James Bay Cree, Inuktitut, Kanien’kéha, and Mi’kmaq.

Areas where one Indigenous language is predominant—such as Māori or Hawaiian—may have an advantage because they begin with a fairly large speaker base and can focus funding, teacher training, and resources on that language. (There are, however, dialectical variations that should be preserved and taken into account as well.)

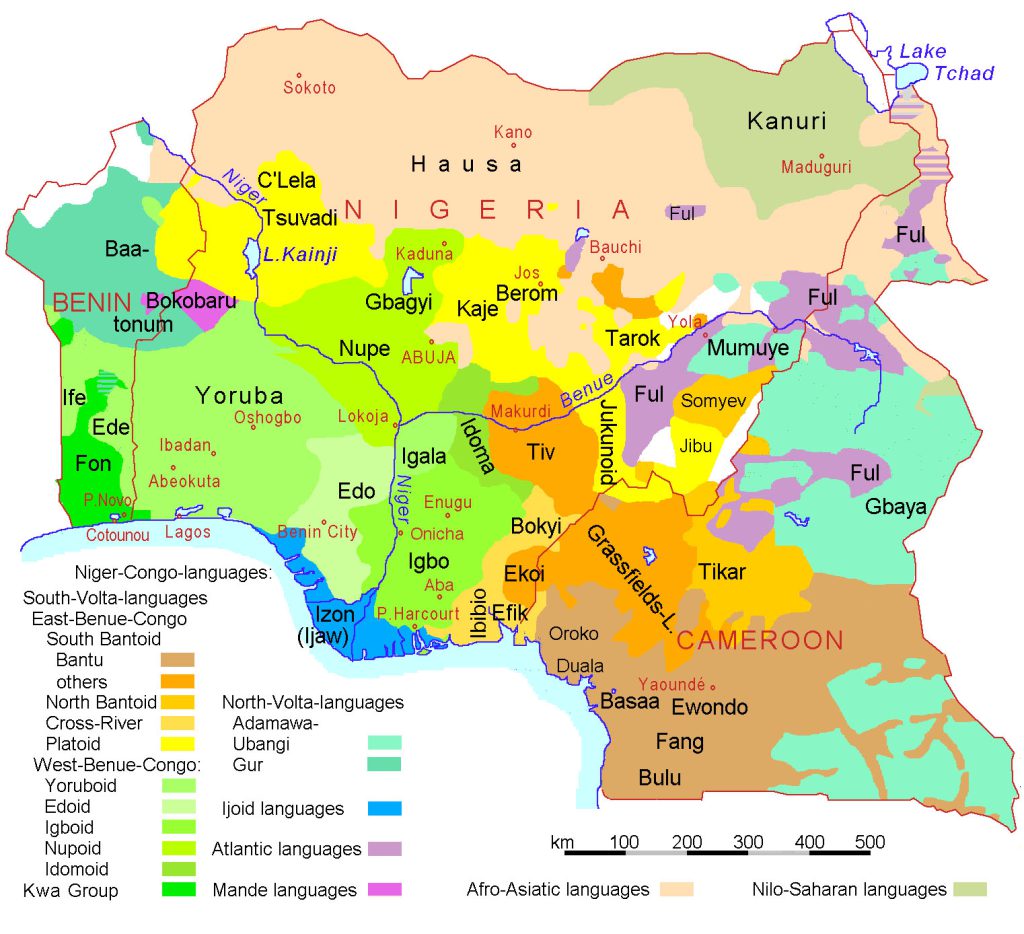

But countries with a high level of linguistic diversity face a serious challenge in the coming decades: How can small languages thrive if speakers gravitate toward using dominant languages instead of their own ancestral tongues?

Bolanle Arokoyo, a Nigerian linguist based at the University of Ilorin in Nigeria, knows that the problem of language erosion in her country is complex. “Nigeria has about 500 languages, most of which are affected by local and global languages,” she notes. “The loss of a language translates into the loss of an entire system of knowledge, communication, and beliefs—hence the need for revitalizing Nigerian languages.”

Arokoyo is dedicated to documenting and reviving Nigerian languages such as Olùkùmi and Owé (a dialect of Yorùbá). She says active community involvement in language revitalization is a crucial component in long-term success. “In Olùkùmi communities, Olùkùmi names are now given to help young people connect to their roots. Conscious efforts are also made by the elders to ensure that the children speak the language.”

Those efforts are supported in local schools by creating accessibility to an Olùkùmi dictionary and other educational materials that Arokoyo has produced in collaboration with fluent speakers, with support from Living Tongues Institute for Endangered Languages.

Around the world, communities are also creating cultural events such as traditional culinary workshops, nature walks, language retreats for adults, language camps for teens, language arts festivals, film screenings, and contests where newcomers and experts can connect with a particular language and cultural group.

Arokoyo says radio is also a great community resource for transmitting endangered languages. Owé speakers launched an “Owé on the Radio” program on Okun Radio, a Nigerian station that is broadcast locally and disseminated online for members of the Nigerian diaspora.

Thanks to radio’s relatively low cost and ability to provide important local information, Indigenous radio stations are thriving around the world, including in countries with high language diversity, such as Canada.

In addition to radio, television is helping languages stay relevant by having a daily presence in the lives of speakers near and far. In Wales, a dedicated Welsh language television channel broadcasts hit dramas to the region’s 874,700 speakers. Peru has TV programs dedicated to the Quechua, Asháninka, and Aymara languages.

In some places, such as Latin America, launching such community-based approaches can be an uphill battle. For example, a passage in Mexico’s Federal Telecommunications and Broadcasting Law stated that all Mexican mass media channels should be broadcast in Spanish, the national language. In 2016, Mexico’s Supreme Court found that passage to be unconstitutional, ruling in favor of representing the country’s linguistic diversity in Mexican media.

The internet can serve as connective tissue that links speakers together over vast distances.

The ruling was a victory for Indigenous language broadcasters, as well as artists, writers, commentators, and journalists who create content in Indigenous languages for radio, TV, and other mass media. It also set the stage for language revitalization efforts to gain more national recognition and opportunities for dissemination.

Languages that are under threat must also have a strong presence in digital spaces, Arokoyo says. In Nigeria, Owé still has a large speaker base, but young people have only partial fluency. The dialect is fading from usage in daily life. So, Owé speakers started a Facebook group where learners discuss words, proverbs, and idioms, plus ask questions and address social issues.

The internet can serve as connective tissue that links speakers together over vast distances. In Cornwall, the “new generation of Cornish speakers … found one another online and leveraged digital spaces to speak on a daily basis,” language activist Daniel Bögre Udell noted in a recent TED Talk. “From there, they organized weekly or monthly events where they could gather and speak in public.”

In addition, Bögre Udell co-founded Wikitongues, an online network of language proponents from more than 70 countries. The website Rising Voices offers microgrants, mentoring, and networking opportunities. Language-learning apps and a mobile-friendly Talking Dictionary app by the Living Tongues Institute for Endangered Languages help communities create and access language resources online.

It is also important to increase the visibility of minority languages in spaces such as streets, schools, and the local and national press. While Canada still has a long way to go in elevating the languages spoken by First Nations peoples, the City of Montreal recently changed the name of Amherst Street to the Indigenous Kanien’kéha (Mohawk) term “Atateken,” which loosely translates as “brotherhood” and denotes peace and fraternity. This tiny act of decolonization helps roll back the influence of colonialism and highlights the original linguistic landscape that characterized the city.

The experience of seeing, hearing, and reading words and phrases in endangered languages celebrates their existence and longstanding historical presence. It also helps dismantle oppression, improve well-being, and increase speakers’ self-esteem by reinforcing the fact that they have the right to speak their languages.

Another way for Indigenous communities to reclaim their ancestry following centuries of colonization and cultural assimilation is by bringing a language back from extinction. When it comes to dormant languages (those that have lost their last speakers decades ago but still retain some social uses), creating an entirely new generation of speakers is difficult but not impossible.

In Louisiana, the Kuhpani Yoyani Luhchi Yoroni (Tunica Language Working Group) is revitalizing the Tunica language, whose last speaker died in the mid-20th century. Linguist Andrew Abdalian, a member of the working group, says the project’s goal is “reintroducing Tunica as a language of the home, with intergenerational transfer.” The team has published children’s books, created a standardized spelling system, compiled a textbook, held weekly classes for tribal youth, and hosted a language and culture summer camp.

The Tunica-Biloxi Tribe of Louisiana recently received an Administration for Native Americans grant for a mentor-apprentice program, which will cover the costs for five tribal members to study their ancestral language full time for three years. “This will help expand the tribe’s teacher base, as well as provide more vectors of language transmission,” Abdalian says.

Meanwhile, Dr. Marvin “Marty” Richardson, director of the Haliwa-Saponi Historic Legacy Project in North Carolina, has worked for decades to reconstruct and revive the Tutelo-Saponi language using legacy materials, recordings, interviews, and linguistic publications.

“Bringing back our language is very important because it is essential to our identity and maintaining our traditional culture,” Richardson says. “Through colonialism, most of our traditional culture has been lost. But with commitment and effort, we can revitalize many aspects of our culture and teach it to the next generation. Language is a central aspect of our tribe.”

One way members of the Haliwa-Saponi Indian Tribe integrate and elevate their language is by writing song lyrics in Tutelo-Saponi. “Drum groups such as Stoney Creek, Red Clay, and others make songs in the language to preserve [it] and to be able to communicate to the dancers and to honor individuals,” Richardson says.

Richardson composed the song “Lone Eagle” in honor of his friend Aaron “Lone Eagle” Montez, a member of the Chickahominy Indian Tribe who died tragically several years ago. The lyrics are “no:na yį’ki so:ti yamąhiye hu:k witaxé: yą:ti itą’:” (“Young strong singer, a friend to all with a big heart, spirit”). Writing such a powerful piece of art carries Montez’s memory forward and creates a new anthem for young singers to embrace.

Languages are a fundamental right and the cornerstone of humanity’s diverse cultural identity. Speaking a dominant language does not mean communities have to give up their right to maintain and promote their ancestral language locally and globally. With public support, funding, access to tools, and recognition, speakers of endangered and dormant languages can change the course of history and reclaim their ancestral tongues for generations to come.