Can This Indigenous Language Thrive in a Digital Age?

On any given day, people throng the busy market in Concepción, Paraguay. Shoppers peruse the multicolored array of fruits and vegetables and occasionally pause to chat with the vendors or inquire about a price. Old women eye up potential buyers of yuyos, traditional medicinal herbs that they assure will cure any ailment, from hangovers to high cholesterol.

As people shop, gossip, and barter, they speak overwhelmingly in Guaraní. The most widely spoken Indigenous language in the country, it is used by more than 5 million Paraguayans. In a country of 6.8 million people, that’s a substantial number.

Guaraní is unique for several reasons. It’s the only Indigenous language in the Americas spoken by a majority of the non-Indigenous population. It has also survived centuries of colonialism and repression.

But beyond the streets or rural areas, Guaraní is conspicuously absent. Although written works in Guaraní exist from the 17th century forward, today it is primarily considered an oral language. And that, says anthropologist and Guaraní activist David Galeano Olivera, is a problem, particularly as societies become increasingly digital.

“We all live in two worlds: the concrete world and the virtual one,” Galeano says. “We have to think about what would happen if, in the virtual world, everything happened in Spanish and nothing in Guaraní. For me, that would mean that Guaraní didn’t exist anymore.”

“It’s impossible to understand Paraguay without Guaraní,” says anthropologist David Galeano Olivera.

Galeano has refused to allow the language to rest on such shaky foundations and so is working hard to bring the language into the digital realm, as other language advocates have done. In 2013, for example, he, along with Guaraní speakers from state and private groups, created a Guaraní version of Mozilla Firefox, or Aguaratata, as it is known in the Indigenous language. The effort represented more than two years of work and required translating some 45,000 terms.

Galeano’s work and collaborations with academics and enthusiasts around the world have a common goal: to keep Guaraní alive. Guaraní is not just a language but an integral part of being Paraguayan, he believes. “It’s impossible to understand Paraguay and its past, present, and future without Guaraní,” he says.

This digital effort marks just one chapter in this resilient language’s history. But it could be a model for how other Indigenous or threatened languages the world over could survive in the age of the internet.

Today it is impossible to visit Paraguay without having to speak Guaraní. Traditional food and drink, such as an iced maté drink, tereré, and a typical bread called chipa, have retained their Guaraní names. There is even a Guaraní version of the Paraguayan national anthem.

“The situation in Paraguay is unique,” says linguist Shaw N. Gynan, an emeritus professor at Western Washington University in Washington state. “In no other New World country does the vast majority of the non-Indigenous population in the entire country speak one Indigenous language.”

During the War of the Triple Alliance in the late 19th century, which saw Argentina, the Empire of Brazil, and Uruguay in league against Paraguay, generals of the Paraguayan army sent messages to one another in Guaraní so their enemies would be none the wiser if they were intercepted. Today Paraguayan football players still use this tactic to baffle their opponents.

Unlike hundreds of Indigenous languages that have been wiped out in South America since the period of European colonialism began in the 1500s, Guaraní has survived. Several factors contributed.

In 1524, Spanish colonists reached the isolated region of South America that is now Paraguay. Instead of fighting, they made contact with the Guaraní people, whose chiefs realized that if they let the Spaniards marry their daughters, they and the conquerors would become tovaja—a Guaraní word meaning brother-in-law. Once they gained this status, they were safe from harm, as their new family members would not kill them.

Spaniards amassed 10 to 20 wives each, which in time resulted in a huge mestizo population (people of mixed European and Indigenous heritage) who grew up speaking Guaraní. In just one generation, a bicultural demographic grew to match the number of Spaniards in the region, and two centuries later, they outnumbered the Guaraní people.

But the language was hardly fostered by the Spanish Empire. In 1770, King Carlos III of Spain issued a decree that prohibited the use of Indigenous languages in his colonies.

And even after independence in 1811, Paraguayans had a complex relationship with their country’s tongues. In 1967, the National Constitution recognized Guaraní and Spanish as national languages. However, the Indigenous language was still excluded from certain official realms, such as in judicial and administrative contexts. Some Paraguayans today still remember being forced to kneel on salt grains and maize for hours as a punishment for speaking Guaraní at school.

In more recent decades, the Paraguayan government has tried to restore pride in the Indigenous language that is spoken by so many in the country. To further promote the use of Guaraní, the government created the Languages Law in 2010, which, among other stipulations, requires that all public officials learn Guaraní and that children start school in their first language, as opposed to forcing all students to speak Spanish.

However, Galeano says, such efforts are still not enough. Monolingual Guaraní children still struggle at Spanish-only schools, and Guaraní speakers still find it difficult to access public services in their language. “Guaraní has been stigmatized … since the beginning of contact,” Gynan says. He describes it as “the underdog language.”

In response, Galeano has spent 34 years fighting for Guaraní to be seen in a positive light, in Paraguay and beyond. In 1985, he founded the Institute for Guaraní Language and Culture to promote the language.

The institute, which has no state funding, has helped change attitudes toward the language, Galeano says. Just a few decades ago, radio DJs and their guests would have had to ask permission before speaking Guaraní. Now such requests are unnecessary, and monolingual Guaraní media is much more prevalent.

These changes don’t mean the battle is won, however. “Compared to the time when people were beaten, the punishment has disappeared,” Galeano said. “But still—and we have to recognize this—there are people who don’t like it. There is a sector, an oligarchy … and they have power.”

Upper-class Paraguayans often attend expensive private schools where they learn English, not Guaraní. The current president of the country, Mario Abdo Benítez, only speaks a few phrases of the Indigenous language but capitalized on them to gain the support of the rural working class, the majority of which uses Guaraní as a first language. The class divide between the languages remains a barrier to Guaraní speakers participating in government, high-paying industries, and other powerful sectors of society.

One way to give lower-class Guaraní speakers a leg up in society is to insert their language into the digital sphere. “Forty percent of Paraguayans are still monolingual in Guaraní, so these online tools are extraordinarily useful for them,” Galeano says.

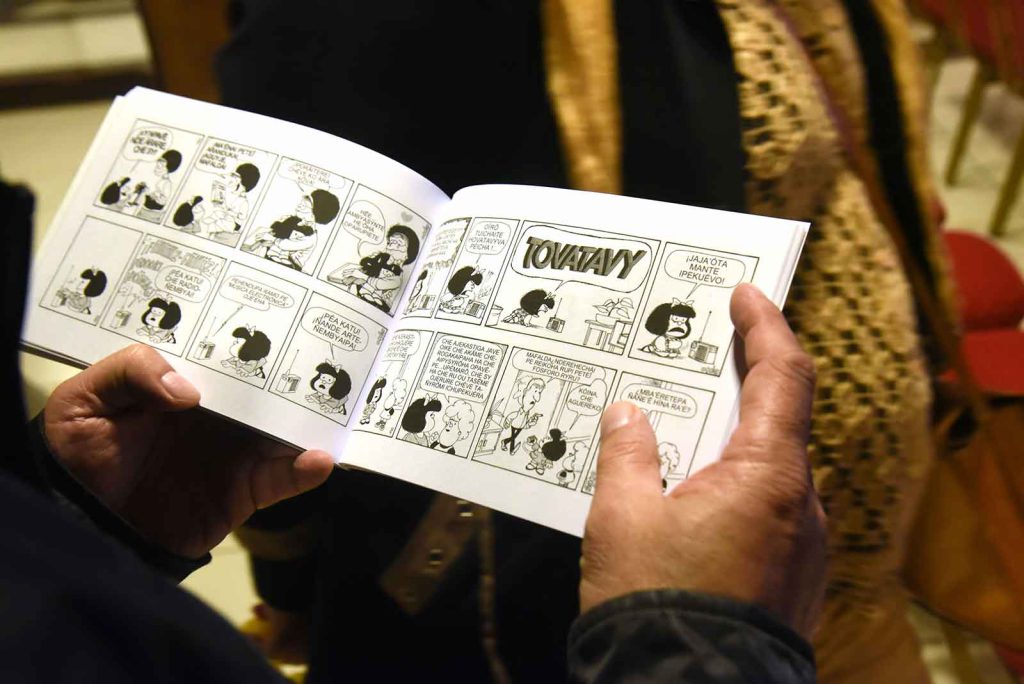

In addition to developing a Guaraní translation of Mozilla Firefox, Galeano and his collaborators created a Guaraní-language Wikipedia—or Vikipetã, as it is presented using the Indigenous language’s phonemes—in 2007. The site now has more than 15,000 entries and is still growing.

Galeano hopes that online spaces such as Vikipetã will be a permanent resource of Guaraní stories, history, and culture for coming generations. The next project will be translating the free software LibreOffice, making Guaraní-language resources available across the globe.

By no means is this effort a panacea or the surest way to ensure Guaraní’s vitality—but it offers a simple and powerful step to preserve the language and support its speakers. “The internet is invaluable for Guaraní,” Galeano says, “above all because it projects the language into the future.”