Can an iPhone App Help Save an Endangered Language?

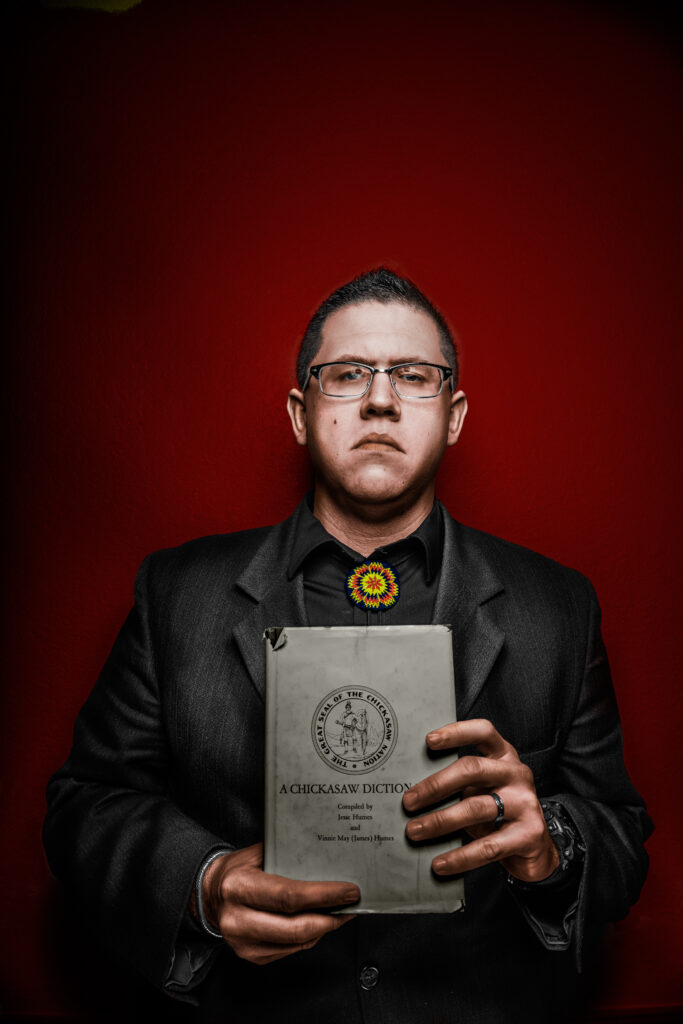

Joshua Hinson’s first biological son was born in 2000. His son’s birth marked the start of the sixth generation that would grow up speaking English instead of Chickasaw, which was the primary language his ancestors had spoken for hundreds of years. Hinson was born in Memphis, Tennessee, and grew up in Texas. Other than a small handful of words, he knew almost nothing about his ancestral language—formally known as Chikashshanompa’. Hinson had a few pangs of sadness over the years about what was lost, but it didn’t really affect him—until his son was born.

As he counted the 10 tiny fingers and 10 tiny toes of his firstborn child, Hinson realized he had nothing to teach his son about his Native American roots. The only thing he had to pass on was his tribal citizenship card. Hinson wanted to bequeath more than just a piece of paper; he wanted his son to be a part of Chickasaw culture. He recognized that the most direct way to understand his culture was to speak the language. But to make that happen, Hinson had to start with himself.

“I had family stories, but not the lived experience of being an Indian,” says Hinson. “I wanted to become a better Indian, and what better way than learning the language.”

As Hinson began to learn the Chickasaw language, he found that native speakers were in perilously short supply. In December 2013, the last person on the planet who spoke only Chickasaw, Emily Johnson Dickerson, died at the age of 93 in her home in central Oklahoma. Less than 100 tribal members remained fluent in Chickasaw, although they could also speak English. All of these individuals were over the age of 60, and no one under 35 could speak conversational Chickasaw. None of the rest of the tribe’s 62,000 members knew more than a few words of Chickasaw. After months of searching, Hinson apprenticed himself to a fluent speaker of Chickasaw, ultimately leaving Texas to move back to the center of tribal life in Oklahoma in 2004. By 2007, tribal leaders had appointed him to direct a project to revitalize the Chickasaw language.

“My goal was to get more people proficient in Chickasaw as quickly as possible,” Hinson says.

Hinson wasn’t just fighting to preserve a fading language, he was also racing against time. To keep Chickasaw alive, Hinson not only had to teach children how to speak the language—he also had to convince them that it was worth speaking.

“Once parents stop teaching the language to their children, it becomes an extracurricular activity, particularly for youth,” Hinson says. “Language is up against softball and basketball and football.”

Languages also have to compete with technology. Digital media is becoming an integral part of Chickasaw life, just as it is in nearly every corner of the globe. But rather than pointing to technology as contributing to language loss, as some linguists have done for decades, Hinson decided to embrace technology as an opportunity. As someone who relies on the internet, he saw it as a potential route to success, not a barrier.

With the tribe’s backing, he began to build an online presence for his tribe—all in Chickasaw. Hinson’s efforts to revitalize the Chickasaw language are also reflected in a larger movement wherein speakers of endangered Indigenous languages are turning to digital technology to preserve their past and adapt to an ever-changing world. The latest technology may just provide a way to help save some of the world’s most threatened languages.

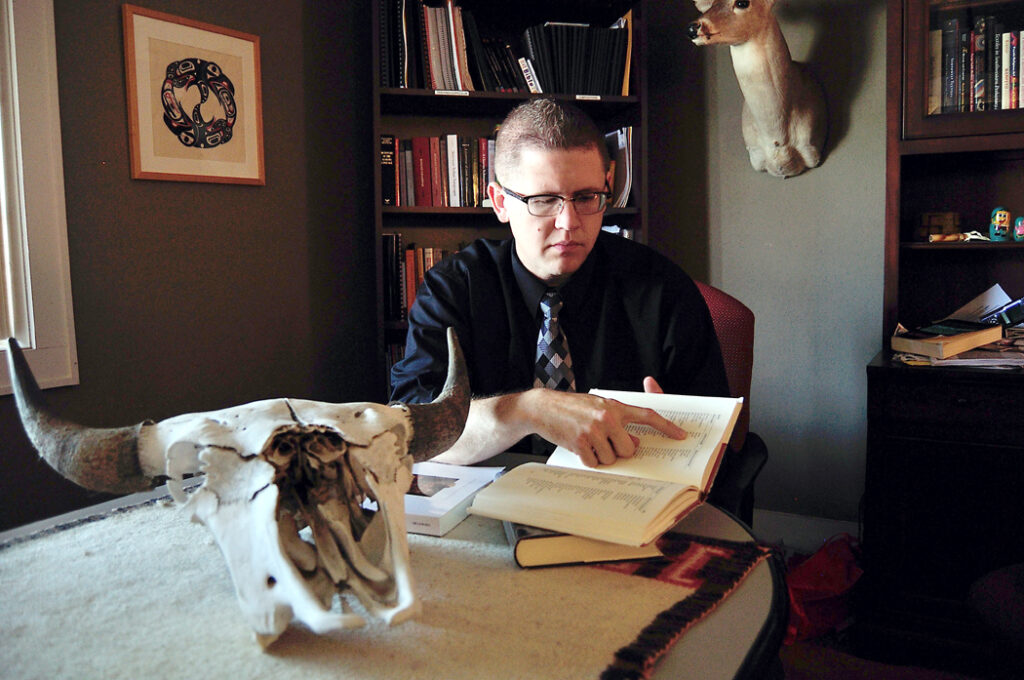

Languages have always cycled through their own stages of birth, change, and disappearance. As cultures move and evolve, interacting with the world around them, so do their languages. That languages shift and dominate other tongues isn’t necessarily a bad thing, explains Bernard Perley, a linguist at the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. What worries linguists and anthropologists isn’t simply that Indigenous languages are fading to silence but that so many are doing so at such a rapid rate. UNESCO, the U.N. division that works to protect the world’s culture and heritage, now estimates that half of the world’s 6,000 or more languages will no longer be spoken by 2100 if action isn’t taken to reverse this trend.

A language provides more than a way to communicate—it offers a unique worldview. It’s almost impossible to fully appreciate a group of people without understanding their language. When a language falls silent, both wisdom and basic information are often lost, such as knowledge about healing plants and natural disaster risks. (For example, even today, Navajo healers hunt among the towering buttes and rust-colored arroyos of the desert Southwest for a pop of bright purple from the tsédédééh, a flower used to treat mouth sores.) Language loss can also lead to the disappearance of more abstract concepts like Ilooibaa-áyya’shahminattook, the lyrical Chickasaw word meaning, “We used to gather together regularly, a long time ago.” Such losses cut a culture from its roots, setting its people adrift in a strange world.

Beginning in the late 1700s, policies enacted by the U.S. government attempted to do just that by actively seeking to eradicate the languages and cultures of Native Americans, who were deemed to be little more than “savages.” But even in the face of annihilation, as the Chickasaw Nation saw their numbers plummet due to disease and then were force-marched from their homeland in the Southeast to Oklahoma on the Trail of Tears, their language remained strong. It wasn’t until Native children were forced into boarding schools and forbidden to use their ancestral language that Chickasaw began to decline in earnest. This severing happened to Hinson’s great-grandparents in the 1920s.

“This had a terrible effect on Native American languages,” says Pamela Munro, an expert in Indigenous languages of the Americas at the University of California, Los Angeles. “Some parents became reluctant to pass on their language to their children.”

It is this history that has led to the dire circumstances many Indigenous languages in the U.S. face. Researchers are aware that speakers of Indigenous languages are dying out much more quickly than new speakers are being born, creating one of the classic scenarios of an endangered language. The professional call to arms occurred in 1992 when a series of papers published by the Linguistic Society of America brought international attention to the extent of worldwide language loss. As a result, professional linguists joined a global movement that used traditional ways of preserving languages while simultaneously searching for new methods. From a scholarly standpoint, the tactic made sense, but this approach wasn’t always what speakers themselves wanted or needed.

“Linguists are trained to write academic papers that tend to be quite technical and often don’t have applied uses,” says Lenore Grenoble, a linguist at the University of Chicago. “Even if you write a grammar of a language, it’s often too technical for speakers to use.”

Several Indigenous communities have cultivated linguists from their own groups and have begun to claim more power and authority over preserving their own languages. As a result, the larger global movement to save Indigenous languages has increasingly relied on community-based efforts. Hinson wasn’t a professional linguist, but he had a strong vision for how he wanted to rebuild a community of Chickasaw speakers. After nearly a decade of work, he knew enough Chickasaw to hold conversations as well as to read and write. He had made so much progress that he began working on a new, full-time project to help save his tribe’s language.

The Chickasaw Language Revitalization Program, founded in 2007, took a two-pronged approach, pairing novice speakers with older speakers who were fluent in the Chickasaw language, and using technology to reach a wider audience. Language learners were paired with expert speakers in a master/apprentice program for immersive lessons that lasted several hours a day, five days a week. Hinson credits his ability to learn so much of the language in just a few years to this type of approach and to his own dogged determination. Under Hinson’s direction, the tribe also built an online television network with six different channels that include language lessons, cultural events, and oral histories. The movement rapidly gathered a strong social media following on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

Television and social media worked wonders for sparking interest in learning Chickasaw, but they didn’t always help with the day-in, day-out needs of students like Hinson who were trying to incorporate the language into their daily lives. In most cases, this is where the master/apprentice course would take over. However, given the small number of fluent Chickasaw speakers, many of whom were aging, Hinson knew that over time the master/apprentice program alone wouldn’t be enough to reach a sufficient proportion of the Chickasaw Nation’s members to help the language endure.

In contrast to some stereotypes non-Natives hold about tribal peoples, tribes have modernized—mobile phones and the internet are just as popular on reservations as they are in the rest of American culture. A substantial proportion of the Chickasaw own smartphones and have internet access at home, and these numbers are even higher among young people, just as elsewhere in the world.

To Hinson, this technological access offered promise for reaching the people who were most likely to keep the language going. Inspired by the success of the Chickasaw TV and social media efforts, Hinson decided to build a smartphone app to help reach even more people.

Working with third-party developers, Hinson created an app for iOS and a website for Android phones and other computers to give new speakers a foundation in Chickasaw. Besides teaching the alphabet, essential words and phrases, and methods for constructing a sentence, the app also contains recordings of native speakers to model pronunciation and cadence. Tribal leaders supported the app, which was launched in 2009, but Hinson had no idea if it would translate into more people learning the language.

The app was an instant hit. As young people began showing more interest in learning to speak Chickasaw, they sparked their parents’ interest too. Hinson’s eldest biological son, now 16, as well as his younger children have all benefited from the app and from having a father who is a proficient Chickasaw speaker. Hinson observed that some families began labeling household items with their Chickasaw names to encourage everyone to use their heritage language, even if just in passing.

Read more from the archives: “How to Resurrect Dying Languages.”

“People have to find the language useful. Language is a tool, and you can put it aside and forget how to use it,” says Salikoko S. Mufwene, a linguist at the University of Chicago. Mufwene grew up in the Democratic Republic of Congo speaking Kiyansi, a Bantu language, until he left home for college.

“Even though Kiyansi is one of the first languages I spoke, I’m now least fluent in my own mother tongue,” says Mufwene, because he currently uses the language so infrequently. By contrast, new Chickasaw language users have more opportunity to practice the language, and the smartphone app is helping to transform Chickasaw into something new and useful. To University of British Columbia anthropologist Mark Turin, giving an endangered language a new sense of purpose is perhaps the most important aspect of digital efforts to preserve and teach endangered languages.

“These things help leverage and engage people,” Turin says. “They provide new domains of use and help to bring people together around a common language, even those who don’t live together.”

Other Indigenous tribes are also using digital technologies to save languages that are thousands of years old.

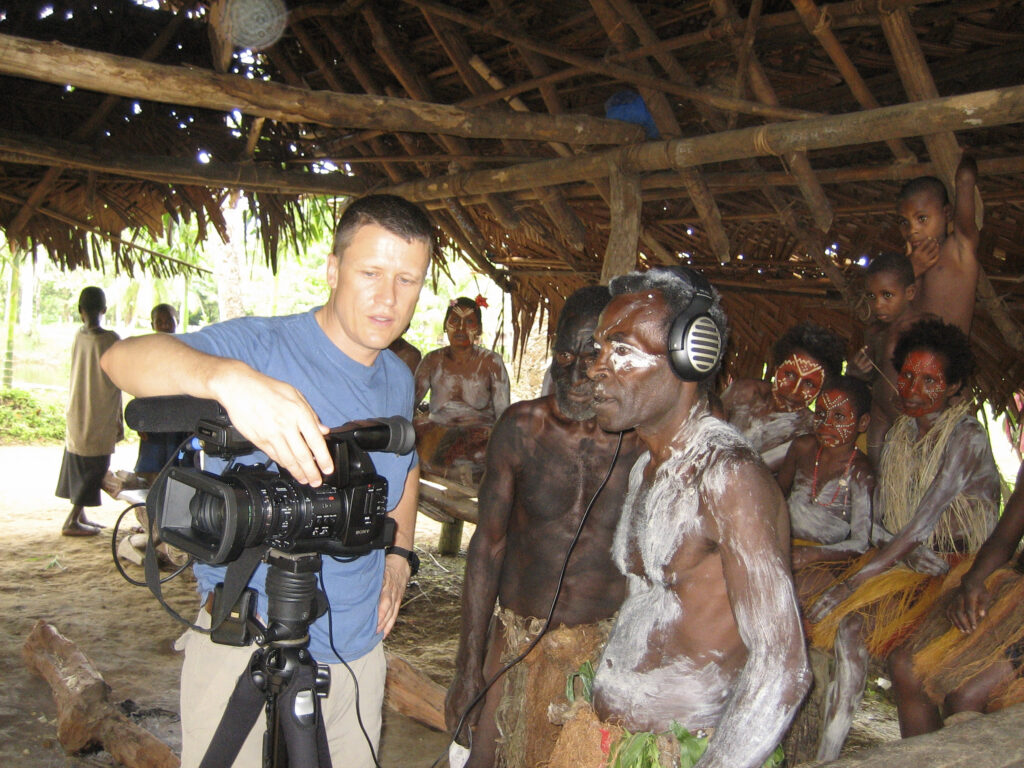

The Living Tongues Institute for Endangered Languages—a nonprofit that connects linguists with Indigenous language speakers and activists in order to save endangered languages—has created multimedia toolkits to allow people to use video, audio, and other technologies to preserve their language. Swarthmore College linguist K. David Harrison is working with tribes in Papua New Guinea to build talking dictionaries as part of an effort to teach these native languages to the next generation, and, with that, to preserve and pass on ancient knowledge about plants, animals, and the world.

The Miami Tribe of Oklahoma, together with Miami University of Ohio, has launched a pioneering language-revitalization program. The Myaamiaki Project, founded in 2001 and now called the Myaamia Center, pairs research into the Miami tribe’s language and culture with practical, on-the-ground revitalization efforts. In Canada, Perley (the University of Wisconsin linguist), who is also a member of the Maliseet Nation from the Tobique First Nation of New Brunswick, has helped revitalize a variety of tribal languages through similar efforts and has observed other tribes taking comparable steps.

Specifically, Perley has worked with a variety of Native American tribes to help them develop lessons and other programming. Early on, one of the teachers he spoke with wasn’t sure his students would use Tuscarora, the Indigenous language of a Native American tribe along the East Coast of the U.S. and Canada, outside of the classroom. As soon as class was over, everyone seemed to switch back to speaking English. However, when the teacher listened more closely to a group of kids playing cards at a picnic table during recess, his perspective changed. The boys were playing a game that involved a lot of counting, but instead of using English for the numbers, they were counting in Tuscarora. All on their own, they had begun using their tribal language in their everyday lives.

“It’s this emergent vitality, these creative uses that make language more relevant,” Perley says.

And these successes build on themselves. The more languages are seen as useful and important, the more they are put into use, explains Grenoble, the University of Chicago linguist. “We don’t want these languages to be museum pieces, we want them to be a part of life.”

Anthropologists at the Living Tongues Institute are working with Indigenous communities around the world to put endangered languages back into regular usage. Besides simply documenting these languages, researchers and speakers are collaborating to create talking dictionaries and other technologies that help the languages thrive again.

“People around the world will be able to go online and hear someone speaking their language,” says Anna Luisa Daigneault, a development officer at the Living Tongues Institute.

STILL, MUFWENE CAUTIONS, technology alone won’t save a language. Many languages in Africa have continued to thrive despite ongoing colonialism, in part because opportunities to speak them remain. These languages are spoken on the job, within families, in primary schools, and in religious ceremonies. Teaching children to speak a language will only help if they are also provided with ample opportunities to use that language. In other words, some of the work of saving endangered languages has less to do with linguistics and more to do with economics.

“If you revitalize a language, you need policy and political structure to maintain it,” Mufwene notes.

Hinson agrees that the app and programs he and the Chickasaw tribe have created aren’t a cure-all. Instead, he sees them as a spark to help light the fire to maintain the traditional language. His vision doesn’t require that every single Chickasaw citizen become fluent in Chickasaw, but it does require that large numbers of them value the language and provide resources to maintain the apps and other technologies.

“An app won’t make you a proficient speaker, but it can help you learn the language,” Hinson says.

These high-tech solutions have also influenced the way many speakers view their own language. Before, some speakers of Indigenous languages perceived their mother tongue as a relic of a bygone era. The insertion of the language into new technologies and contexts, however, makes it seem shiny and new—like something relevant to the technological era. This will likely help today’s children pass the language on to their own children. A language’s transmission is key to keeping it alive, many linguists say.

For his part, Hinson continues to develop other language technologies for the Chickasaw to use. Recently, the tribe partnered with the popular language-learning software company Rosetta Stone to create a series of 80 Chickasaw lessons. Rosetta Stone has already created similar lessons for the Navajo and Mohawk communities.

“It’s a constant process of creating new speakers,” says Hinson. “When this generation has its own kids, then we’ll know if it’s working.” His children are soaking up their language and its surrounding culture. Hinson says it’s their intention to teach their own children Chickasaw someday.

“My dream is that as an old man, people will come up to me and say they’ve decided to teach their children Chickasaw.”

This article was republished on discovermagazine.com and scientificamerican.com.