Chapter 5

How To Tell a Great Story, Part 2: Style

Dynamic writing transforms a story without losing the essence of your central idea.

INTRODUCTION

Writing with skillful style is where magic happens.

Getting the structure of a story nailed down is satisfying work, but it can sometimes feel like heavy lifting. You’re starting with the foundation of a blank page and constructing the story’s framework, walls, and roof, making sure everything fits together and holds up. Once you’ve accomplished that, it’s time to splash on color and add decorative flourishes.

When it comes to storytelling, style is just as important as structure. Adept style evokes suspense, delight, and emotion in readers. It helps your messages stick in people’s minds. It makes learning more meaningful and fun.

So in this chapter, we’re going to get creative. We’ll show you how to give your articles a jargon-free makeover without dumbing them down. We’ll cover the elements that can make your writing sing, from cliffhanger transitions to musical pacing to words that strike like lightning bolts.

The Epic of Gilgamesh is the world’s oldest known written story. Here is a fragment from Iraq, dating to more than 4,500 years ago. This tale is entirely recognizable today as a hero’s adventure.

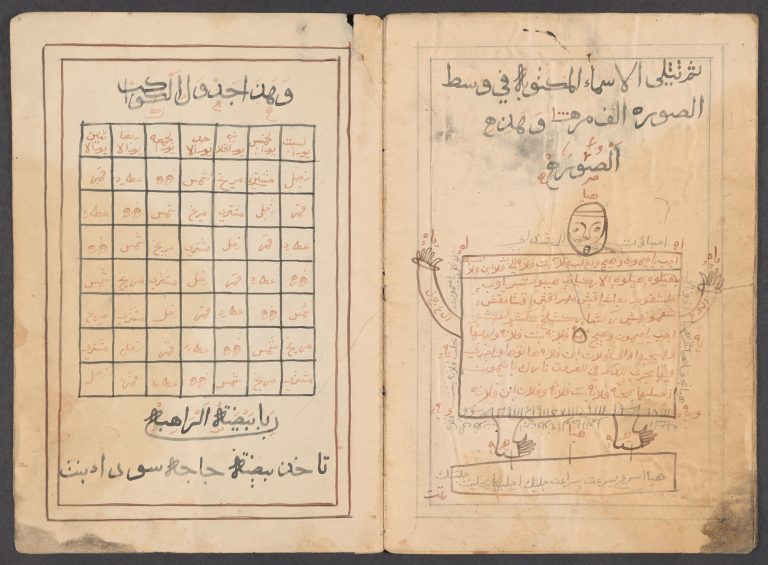

Arabic likely was first written about 1,700 years ago, used through the ages to inscribe gravestones, record religious stories, pursue science, document history, and far more.

TRANSFORM JARGON AND ACADEMESE

You may have noticed something ironic about anthropology.

Anthropologists tend to be passionate advocates of inclusivity. Yet the conventions of academic publishing mean there are countless anthropological articles advocating inclusion that sound like this: “We contend that these foci, undergirded by Spinozist-Deleuzian approaches, trouble traditional conceptions of personhood and resituate the process of attribution away from figurations based on the internalization of external relations.”

The number of people who can understand that sentence could fit comfortably in a closet.

Jargon is appropriate when you’re communicating with fellow specialists. But jargon excludes most of the world’s population, both because it’s obscure and because it’s usually brain-draining, even to people who understand it.

Throughout this section, we’ll show you that using accessible language does not mean “dumbing things down.” Writing engagingly requires creativity and savvy. It also requires knowing each concept so thoroughly that you’re able to reshape it in multiple ways while maintaining its integrity.

How can you transform academese into engaging language?

First, imagine you’re having coffee with a friend who represents your target audience for public writing: an intelligent, well-informed person who does not work in your field and who knows nothing about your research. Then talk with the friend, either in your mind or out loud. How would you explain your ideas to them? What do you think would most interest them? Is there an analogy that would help them understand a concept? The language you use in this hypothetical conversation will probably sound a lot like the language you should use in your article.

Let’s look at how the coffee-with-a-friend exercise can give academic writing a makeover. In the Knowable magazine essay “Leaning Into Indigenous Knowledge on Climate Change,” writer Chris Baraniuk draws on an article in the Annual Review of Anthropology that includes sentences like this:

Long-term observations of complex systems, considered a hallmark of Western science, are also well documented among indigenous knowledge systems. … Attempts to enfold indigenous climate knowledge into dominant epistemic institutions … are increasing. …

Anthropologists are increasingly interested in ontological pluralism. … This concern permits anthropologists to breach conventional knowledge flows in which scientific expertise filters into technocratic decision making, bringing more and varied perspectives to bear on our climate crisis.

Now we don’t know if Baraniuk imagined explaining that to a friend over coffee. But it sounds like he did. Because this is his nut graf in the Knowable article, and it effectively translates the above jargon into accessible sentences:

Today anthropologists and climate researchers in Western institutions are increasingly turning to Indigenous people to ask what they have observed about the world around them. In the process, these scientists are learning that Indigenous communities have been cataloging, in their own way, data about change at a hyper-local level—insights that Westernized climate science might miss—and also how that change is affecting people.

Note how the Annual Review of Anthropology article tends to use passive sentence structure, which is common in academese. In passive voice, the subject receives the action, and the person doing the action is often unmentioned (“observations … are well documented”).

The journalistic article employs active voice, in which the subject performs the action (“scientists are learning”). Writing in active voice is one of the easiest ways to transform academese into journalistic writing. It makes sentences more dynamic, straightforward, and easy to visualize.

Another effective method of giving academic writing a makeover is to provide examples that are visual, visceral, and tangible. For example, the same Knowable essay drew from another Annual Reviews article that features the kind of general, list-like sentences one often finds in academic journals:

There are many examples and further potential for Indigenous peoples’ and local communities’ engagement monitoring, mapping, and reporting changes in local biodiversity, including species’ ranges, baselines, and trends, the presence of pollution, invasive alien species, impacts of restoration programs, or local climate change impacts. … authors of the IPBES Global Assessment report summarized more than 500 local social-ecological indicators from the literature to evaluate status and trends in Indigenous peoples’ and local communities’ lands.

Can you visualize “local social-ecological indicators”? Can you touch, taste, or smell them?

No.

So they wash over the reader’s mind like floodwaters over a desert plain.

By contrast, the Knowable article describes Indigenous people observing the sight of a spring morel mushroom in September, the sound of maple sap freezing and cracking the trees, tick outbreaks that make your skin crawl, and erosion creeping up a beach until there’s no more room for a fish trap that laid there for decades. Those descriptions soak into a reader’s mind and stay there. That’s because sensorial experience is the stuff of story—and the stuff of life.

When you’re giving academic writing a jargon-free makeover, focus on telling a story. Here’s an example. In her original paper in Current Anthropology, anthropologist Karen L. Kramer (and biostatistician Garnett P. McMillan) describe the effects of new technology on the reproductive outcomes of Maya women:

Among traditional populations, an increase in female activity levels has been associated with postpartum anovulation. … Following the introduction of a gas-powered water pump and mill that markedly increased women’s labor efficiency and a positive tip in the energy balance, age at first birth dropped significantly. … Thus, nulliparous young women reallocated the time spent in calorically expensive activities to less energetically costly leisure activities, potentially relaxing the physiological constraints on female sexual maturation. When using the labor-saving technology, women worked on the order of two and a half fewer hours a day, a daily savings of an estimated 325 calories—an amount sufficient, for example, to satisfy the increase in energy expenditure required during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle.

In her SAPIENS essay based partly on this article, Kramer didn’t bother to use and explain the words “anovulation,” “nulliparous,” and “luteal.” Defining jargon terms or replacing them with their definitions is rarely the best approach. If definitions were interesting, people would read dictionaries at book clubs. Instead, Kramer focuses on telling a story:

In the 1970s, the isolated village of Xculoc, in Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula, was home to about 300 Maya people. The maize-farming residents had no electricity or running water. Women hauled water from a 50-meter-deep well using ropes and buckets. They ground maize—the mainstay of their diet—in hand-cranked grinders.

Then two technologies were introduced that changed these Maya’s lives and, ultimately, their population: a gas-powered water pump and two gas-powered maize grinders.

Using these devices, young women saved about two and a half hours of labor and 325 calories a day. In addition, younger siblings could more easily fetch water and crush maize, freeing up their older sisters’ time and literally decreasing their daily grind. That’s important because studies have found that heavy subsistence work suppresses ovarian function, whereas reducing labor and raising women’s energy balance is associated with a bump in fertility.

Note how this jargon-free version unfolds almost like a movie. You can picture scenes with women hauling water and hand-cranking maize. Then, like in a film, an incident happens that moves the plot forward, altering the women’s routines and bodies. Kramer entertains readers with playful puns (“bump in fertility”). And she helps readers process the information with a straight-up explanation of why these facts are important.

Is it ever OK to use jargon in public writing? Yes. If a term people may not fully understand—say, mitochondrial DNA, Acheulean hand axes, or the name of a rare health condition—is central to your article, and you’re going to have to repeat the term multiple times, it’s perfectly fine to use and define it.

A word of caution, though. In academic journals, writers are typically expected to relate their ideas to theories or ways of thinking, such as functionalism or cyborg feminism. The definitions of these jargon terms typically include more jargon terms. It’s often jargon all the way down.

So in almost all cases, avoid naming little-known theories when writing for the public.

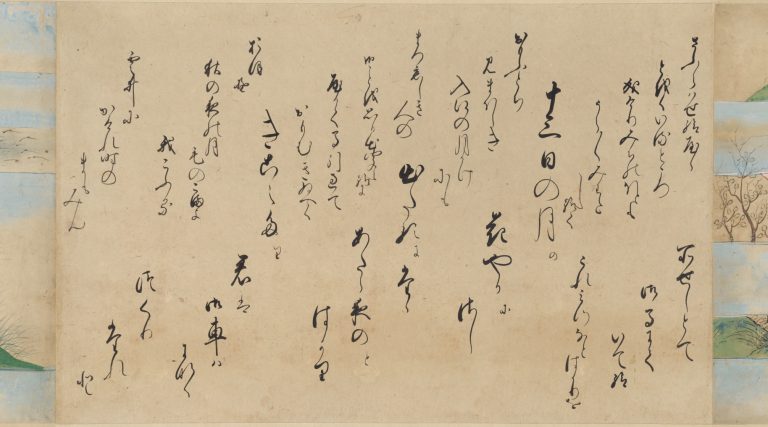

This scroll from 1594 depicts a scene from The Tale of Genji.

COLORFUL CHARACTERS AND QUOTES

The Tale of Genji is a classic piece of literature, among the world’s earliest novels, from 11th century Japan.

Like sensuous description, characters can bring your story to life and make readers care about your topic.

Writing about people and the interesting things they say and do can be a lot of fun. It can also be a minefield of potentially biased and even offensive characterizations or, on the flip side, flat and generic depictions. So whether you’re profiling one person or mentioning several people as part of a larger story, here’s how to approach character development, and how not to.

Many anthropologists may be reluctant to include character descriptions in their writing, perhaps because they want to protect their interlocutors’ anonymity and/or because they may think such descriptions are more suited to fiction than to scientific discourse. However, not including any meaningful character description could do a disservice to your interlocutors by not portraying their humanity, complexity, and relatability.

If you’re concerned about including identifying features, you could instead highlight sensory details about the setting, or describe some aspect(s) of the person’s home or workplace. You might evoke the collective emotions in a community, such as tension, excitement, fear, or ebullience. Or consider taking a cue from Maya Angelou and describe how the person made you feel. Some people immediately soothe you into an almost meditative state. Others are the human equivalent of caffeine. Some people command attention with a magnetic presence. Others quietly captivate with a mysterious aura.

When you’re choosing which details to include, highlight those aspects of a person’s character that are key to the story you’re trying to tell and are the most interesting. In “When Coffee Is Like Angel Cake With Strawberry Jam,” anthropologist Edward F. Fischer explores the rarified world of specialty coffee. Wisely, he humanizes this topic and makes it more accessible by spotlighting specialty coffee brewer Elika Liftee.

Fischer writes: “Born in Japan to an Air Force mother and a Hawaiian father, Liftee grew up in Oklahoma—a typical Midwestern childhood, as he describes it, but with a kitchen stocked full of papaya, guava, and other tropical foods.” Mentioning the fruit in Liftee’s childhood kitchen adds color and personality to the essay. But most importantly, it’s central to the story. Later in the article, we learn that Liftee brews fruity coffees that remind him of his heritage, and this flavor profile is becoming increasingly popular in the specialty coffee arena.

If you Google Liftee’s name, you’ll see he has red-framed glasses and a beard. But the writer doesn’t mention this. Why? Because it doesn’t change the taste of his coffee. And that’s what the article is about.

Describing someone’s physical appearance and clothing can be appropriate and even essential. In this SAPIENS essay, writer Keridwen Cornelius explains that experimental archaeologist Bill Schindler wears brain-tanned buckskin clothing, has a hand-poked tattoo based on a 9,600-year-old bone inscription, and was previously overweight. Why? Because that’s what the article is about: Schindler’s interest in Stone Age skills and his struggles with metabolic syndrome inspired him to focus his career on ancestral diets.

In most cases, though, people’s appearance and clothing are not pertinent to an article. And your description could be influenced by unconscious biases. For example, according to one study, journalists described female scientists’ physical appearance half the time but male scientists’ appearance just one-fifth of the time. Eek!

When it comes to using quotes, you can trust your instincts a bit more. You don’t have to be a screenwriter to know a great line when you hear one. But in journalistic writing, as in screenwriting, it’s important to know when to use exposition and when to use dialogue.

If your interlocutor is explaining something in generalities, you’re better off paraphrasing the person and adding fascinating details from various sources. Great quotes are more likely to be emotionally moving statements, funny one-liners, brilliant analogies, or bold opinions. In other words, they’ve said something in a way that you can’t.

In this SAPIENS essay about people who lost their sense of smell after contracting COVID-19, anthropologist Sarah Ives incorporates several colorful, heartfelt quotes. Her interlocutors express heartbreak and fear over not being able to smell Christmas trees, their boyfriend’s skin, rotten food, or a stove on fire. In this photo essay about potential reunification in Cyprus, anthropologist Anna Antoniou effectively uses opinion-based quotes from Greek and Turkish Cypriots to explore the conflicts and commonalities between the two groups.

GO WITH THE FLOW: EFFECTIVE TRANSITIONS

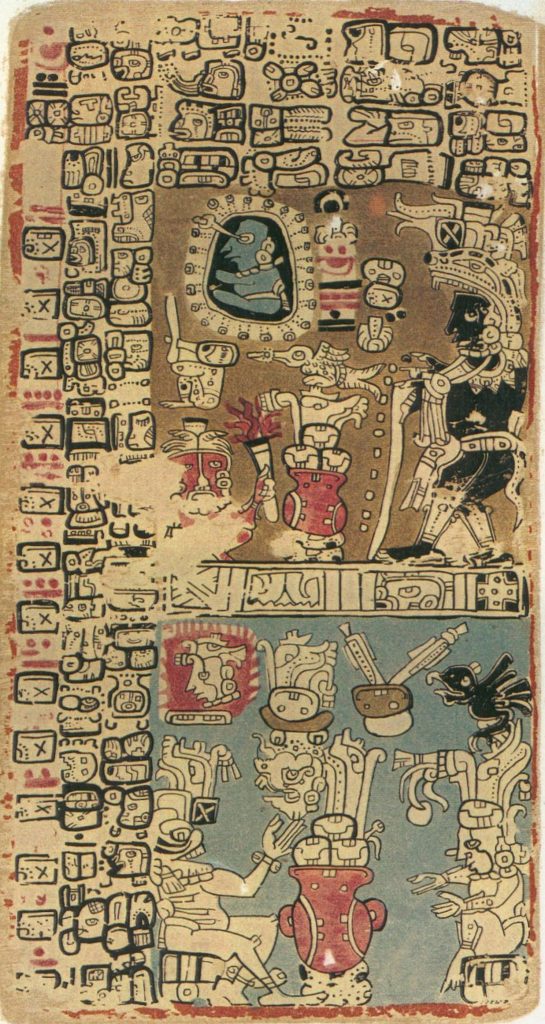

The Madrid Codex was written in the Mayan language about 1,600 years ago.

When you’re reading your rough draft, you’ll often notice that some sentences and paragraphs flow together well, and you feel a satisfying momentum building when reading them. Then suddenly everything comes to a screeching halt. You wonder, “Wait, how did I get from that thought to that thought?”

The solution is transitions. Effective transitions can connect ideas logically. Without them, sometimes readers will miss your point, even if you think it’s clear. Transitions can also act as cliffhangers, catapulting readers into the next section. They can transform a clunky, disjointed essay into a reading experience that flows as sinuously as a symphony.

But how?

(See how that works?)

Transitions can be placed between sections, paragraphs, or sentences. Usually, the goal of a transition between sections is to generate suspense that motivates people to keep reading. One way to do this is to end a section by creating a question in your reader’s mind that you then answer in the subsequent section.

For example, in “Inside Mexico City’s Surveillance State,” anthropologist Esteban Salmón ends a section with this sentence: “Still, surveillance technology is prone to numerous problems, from technological glitches to cognitive biases to outright cover-ups.” That makes readers ask: “What kind of glitches, biases, and cover-ups are undermining surveillance?”

Then they’ll see that the next section is subtitled “THE FLAWS IN SURVEILLANCE SYSTEMS,” and they’ll likely read on to find the answers to their question.

Later in the same article, the author uses a different transition style. In this instance, the first sentence in the new section effectively reaches back and grabs the baton from the previous section:

Police officers have been filmed tampering with videographic evidence, destroying cameras, turning cameras away from an incident, and even stealing storage drives.

DISPUTES OVER THE SURVEILLANCE STATE

For all the above reasons, the expansion of Mexico City’s video surveillance system has not gone unopposed.

Try reading that segment again without “For all the above reasons.” It still makes sense. But it doesn’t flow nearly as well, and the logical link between the sections isn’t quite as obvious.

When transitioning between sentences or paragraphs, you could use transition words or phrases, which can appear at the beginning, middle, or end of a sentence. Or you could repeat words from one sentence or paragraph in the next one.

In the following example, from “Writing Indigenous Oral Tradition to Fight a Dam,” anthropologist Karminn C.D. Daytec Yañgot uses transition phrases between sentences. And she transitions between paragraphs by echoing words about loss:

Lakay Warling bemoaned the fact that his people have to choose between protecting their ancestral domains and leaving in exchange for compensation. “What some of us don’t understand,” he lamented, “is that money is temporary. Once it is gone, it is gone.” When that happens, the Isnag will have lost their money, their river, and their ancestral home.

What they won’t lose, Lakay Warling hopes, is their history and culture. That’s because the Isnag are engaging in an act of cultural resistance: They are writing down their Oral History.

Another way to create cohesion from one sentence to the next can be characterized as the AB, BC, CD method. Each letter represents a word or concept. The writer uses a word in the first sentence, threads that word (or a synonym) into the second sentence, and then incorporates a new concept. Then that new concept gets threaded into the third sentence. In this way, all the sentences feel sewn together.

Here’s an example: “The garden provided a home for numerous species (A). Among the many animals (A), peacocks caught Emily’s (B) attention. She (B) was a biologist who usually studied mammals, but her latest project (C) featured the feathered wonders. That study (C) garnered her a reputation as an eco-feminist scholar.”

Sometimes you need to make multiple points in a section, and you can’t figure out how to get one paragraph to flow into the next. When that happens, you may be missing a logical step and need to add a paragraph. Often, though, all the elements are there, but they’re not in the best order. Try playing around with cut and paste, and see if changing the sequence of your paragraphs helps everything fall into place.

POWERFUL VERBS AND LIGHTNING WORDS

TERMINOLOGY REVIEW

Characters: Someone or something that plays a role in a story.

Pacing: The rate at which a story develops as shaped by the action, characters’ choices, tension, and resolution.

Style: A writer’s choices that give a story its distinctiveness and flavor, and the degree to which it fits into or expands out of different genres.

Tone: The attitude a writer takes toward their story and subject, for example, using funny words to express a playful attitude compared to lyrical words to express a poetic nostalgia.

Mark Twain popularized the saying: “The difference between the almost right word and the right word is really a large matter—’tis the difference between the lightning bug and the lightning.”

Lightning words can shimmer on the page or hit like a gut-punch. Choosing the right word is one of the most fun parts of writing, and it absolutely transforms articles.

That doesn’t mean you need to pack every sentence with fancy-schmancy, multisyllabic words. Those essays feel like fruitcake topped with cookie-dough ice cream drowned in salted caramel sauce. It’s too much.

Instead, zero in on your verbs and see if you can kick them up a notch. Pay special attention to “to be” verbs like “is,” “are,” “was,” and “were,” and try substituting a more interesting verb or reconstructing your sentence to avoid the “to be” verb. Instead of “We were hot and sweaty,” try “Sweat stung our eyes and poured down our flushed faces.” Instead of “The gym is noisy with the sound of dumbbells hitting the floor,” try, as anthropologist Cara Ocobock writes, “My body reverberates with the clangs of hundreds of pounds being dropped repeatedly on the floor.”

The Musalman, published in India, is the likely the last handwritten daily newspaper in the world.

Replacing a ho-hum verb with a powerful action word gives you more bang for your buck than adding adjectives and adverbs. Lightning verbs are likely to do one or more of the following:

- Conjure a visual image: sparkle, splash, sidestep, blur, orbit.

- Evoke a visceral feeling: ache, clutch, squeeze, shoulder, muscle in.

- Sound like what they mean: ooze, squiggle, gulp, plunk, screech, rattle.

- Sound powerful: supercharge, skyrocket, galvanize, emblazon.

- Sound fun: hoodwink, bamboozle, lollygag, flabbergast, vamoose.

In addition, lean toward verbs and other words that convey your desired tone and fit with your theme. If you’re writing about cooking, you could say, “She peppered the culinary archaeologist with questions” or “The new study set off a simmering debate.” If you’re writing about something darker or more serious, puns would probably be inappropriate. But you could choose verbs that sound harsh, bleak, somber, or whatever mood you want to evoke.

Sometimes lightning verbs emerge from picturing a scene or an action in your mind’s eye and using words in innovative ways. It’s kind of like finding a new use for a tool. Consider the following passages from “The Snarled Lines of Justice,” which a group of eight anthropologists and other scholars wrote for the environmental publication Orion:

“This is the story that ricochets between past and present …”

“Dreams of elite hideaways boomeranged …”

“Now most everyone can taste the fumes of the Anthropocene …”

“… slow violence often seeps, disappears, and resurfaces.”

In addition to revamping your verbs, look over your article and see if you repeat certain words over and over. You’ll almost inevitably restate nouns central to your topic; these repetitions are opportunities to provide more information and color.

Let’s say you’re writing about ayahuasca, and you notice you overuse the word. You could instead say “traditional plant medicine,” “psychedelic substance,” “psychoactive Amazonian drink,” “powerful entheogen,” or “thick, brown brew that tastes of prune juice and burnt coffee.” Replacing a noun with a phrase that provides information sometimes allows you to remove boring “to be” verbs and recombine your sentences in ways that are more efficient and interesting.

PACING AND SENTENCE LENGTH

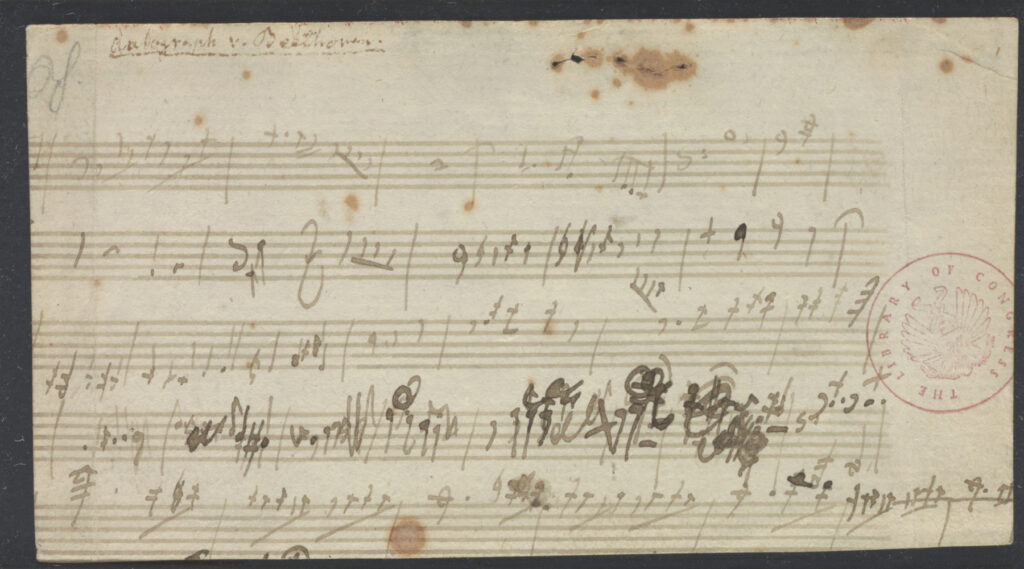

Beethoven, who wrote and signed this sheet of music in about 1790, mastered pacing in the art of music.

Irish poet John O’Donohue once said, “Music is what language would love to be if it could.”

Great writing does indeed sound musical. Rhythm, speed, and percussiveness absolutely matter to the reading experience.

As we said in Chapter 4, your first section should be fast-paced. Think the booming, racing beginning of Ludwig van Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. Then your essay can slow down for a while. But it has to speed up again, or readers will nod off. So if you notice a section is dragging, follow it with another section that accelerates the pace.

Things that speed up the reading experience are character-driven stories, dynamic action, fun or moving quotes, colorful details, short paragraphs, and short sentences. Things that slow down the reading experience include historical context, explanations of methodology or concepts, discussions of theory, jargon, long paragraphs, and long sentences.

Rhythm also matters at the sentence level. If you’re familiar with certain types of traditional drumming, you know that an unvarying beat can literally put people into a trance. You do not want to put readers into a trance. So it’s essential to vary the length and rhythm of your sentences.

Let’s examine the Washington Post op-ed “We Have Slashed and Burned the Core Features of Childhood.” In her lead, evolutionary anthropologist Dorsa Amir begins with longer sentences that flow like violin music. Then, when she makes her main points, she uses shorter sentences that land like drumbeats:

Nearly 100 years ago, a team of archaeologists working in Greenland stumbled onto something strange: careful arrangements of brightly colored stones nestled into the frozen landscape. There was no mistaking they were intentional, the ovals of red and white pebbles, but what were they?

The team traced the formations to the walrus-hunting Thule people of the medieval era, the predecessors of the Inuit. And they assumed what archaeologists often assume, that the structures were religious in nature.

But they were wrong.

The stones weren’t talismans for hunting or warding off evil spirits. They were something arguably more wondrous: children’s playhouses.

If you really want something to reverberate in people’s minds, put it into a short, percussive sentence. And put the most important part (or the most surprising or funny part) at the end of the sentence, so it sounds like a mic drop.

Activities

Practice Self-editing

-

Lightning word activity

Below are three short passages taken from articles and a book. In the first version of each one, dynamic words have been replaced by words in brackets that are perfectly acceptable but not especially interesting.

Try to brainstorm more colorful words or phrases that could be used instead of the ho-hum words in brackets. Then, when you click on “Original,” you can see which words or phrases each author actually chose.

The goal is not to correctly guess the real words or phrases (you almost certainly won’t) but to get creative and think outside the box. You might even like your ideas better than the authors’.

-

“The first Neanderthal face to [be excavated] was a woman’s. As the social and liberal revolutions of 1848 began [changing] Europe, quarry workers’ rough hands pulled her from the great Rock of Gibraltar. Calcite [covering] her skull meant that, at first, she seemed more a hunk of stone than a once [living] being, and obscured her decidedly odd anatomy—massive eyes, heavy brow ridges and a low, long cranium. While monarchies fell and serfs [gained] freedom that year, it would take another decade for human origins as a science to begin its own overthrow of the old world order.”

“The first Neanderthal face to emerge from time’s sarcophagus was a woman’s. As the social and liberal revolutions of 1848 began convulsing Europe, quarry workers’ rough hands pulled her from the great Rock of Gibraltar. Calcite mantling her skull meant that, at first, she seemed more a hunk of stone than a once warm-blooded being, and obscured her decidedly odd anatomy—massive eyes, heavy brow ridges and a low, long cranium. While monarchies fell and serfs breathed the sweet air of freedom that year, it would take another decade for human origins as a science to begin its own overthrow of the old world order.”

-

“The cliffside free fall he is talking about is the day that drug-resistant bacteria will be able to [defeat] the world’s entire arsenal of antibiotics.”

“The cliffside free fall he is talking about is the day that drug-resistant bacteria will be able to outfox the world’s entire arsenal of antibiotics.”

-

“Cancer was an all-consuming presence in our lives. It [entered] our imaginations; it [took over] our memories; it [made its way into] every conversation, every thought. And if we, as physicians, found ourselves [interested] in cancer, then our patients found their lives virtually [destroyed] by the disease.”

“Cancer was an all-consuming presence in our lives. It invaded our imaginations; it occupied our memories; it infiltrated every conversation, every thought. And if we, as physicians, found ourselves immersed in cancer, then our patients found their lives virtually obliterated by the disease.”

-

-

Editing activity

Below, we’ve taken two brief excerpts from an article and a book and purposely rewrote them badly. Try to improve the weak versions, restructuring the sentences and replacing the “to be” verbs with dynamic verbs when possible. When you click on “Improved,” you can see the original versions.

-

Weak: Teotihuacan is about 40 kilometers from Mexico City. It was one of the largest cities in the world between 1 C.E. and 550 C.E. It had many cultures, pyramids, markets, apartments with an estimated 100,000 residents.

“About 40 kilometers outside Mexico City, Teotihuacan rose to be one of the world’s largest cities between 1 C.E. and 550 C.E. The multicultural metropolis featured pyramids, markets, and apartments that housed an estimated 100,000 residents.”

-

Weak: Echolocation is different from the other senses about which we have learned so far because energy is put into the environment during echolocation. Vision involves scanning by eyes, smell involves sniffing by noses, whisking is done by whiskers, and touch is accomplished by fingers pressing. These are sense organs that are always picking up stimuli that are already there in the wider world. By contrast, during echolocation a stimulus is created by a bat and that stimulus is later detected by the bat.

“Echolocation differs from the senses we have met so far, because it involves putting energy into the environment. Eyes scan, noses sniff, whiskers whisk, and fingers press, but these sense organs are always picking up stimuli that already exist in the wider world. By contrast, an echolocating bat creates the stimulus that it later detects. Without the call, there is no echo.”

-