The First Butchers

Living humans, all 7.3 billion of us, are classified as Homo sapiens. That means we are all part of the same species; our genus is Homo, meaning “man,” and our species is sapiens, meaning “wise.” Both genetic and fossil evidence place the origin of our species at about 200,000 years ago in Africa. But when and where did the earliest members of the genus Homo evolve? And what makes our genus unique compared with other branches on our family tree?

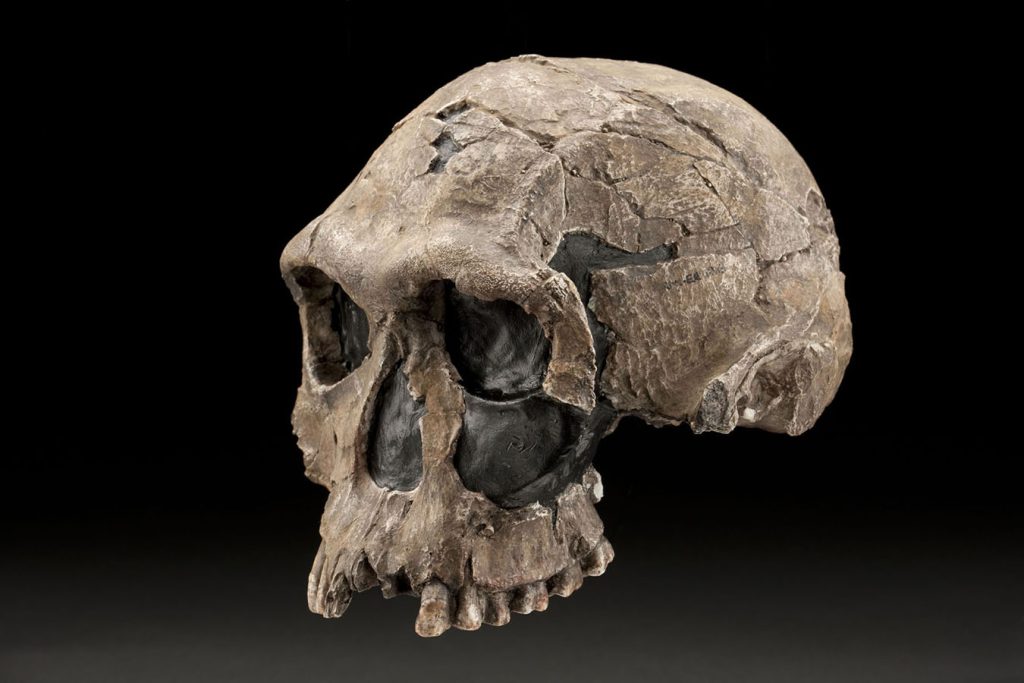

The best candidate, based on current evidence, for the earliest species in our genus is Homo habilis (meaning “handy man”). This species, which was named from fossils found at Olduvai Gorge, in Tanzania, by a research team led by Louis Leakey, was announced in 1964. The team defined the new species based on the specific anatomy of the fossils, including a larger brain and body and smaller teeth than members of the earlier-known genus Australopithecus. But they also did something novel as far as naming a species goes—they linked Homo habilis with the origin of a specific behavior by suggesting that this species was the maker of the simple Oldowan stone tools found previously in the same sedimentary layer. (These tools—which are basically simple stone knives—are made when roundish rocks, called hammerstones, are struck against more angular rocks, called cores, to strike off sharp flakes.) Later, in 1981, when cut marks were found on animal fossils at Olduvai Gorge, they were presumed to have been created by Homo habilis wielding these stone tools to butcher large animals. Homo habilis was declared the toolmaker and the meat eater, and, as a result, a core part of the definition of our genus involved these two novel behaviors.

This narrative held for over three decades, through the late 1990s. In 1997, even earlier stone tools—dating to 2.5–2.6 million years old—were reported from the Gona study area in Ethiopia. In the same year, a new Homo habilis fossil upper-jaw fragment from the Hadar site in Ethiopia pushed the origin of this species back to 2.34 million years ago. Then, in 1999, 2.5-million-year-old stone-tool cut marks on animal fossils were reported from the Bouri site in Ethiopia, along with percussion marks made on bones when early humans smashed them open with stones to retrieve the nutritious marrow inside. Even with this new evidence, though, the correlation persisted, and this package of new traits—larger brains, stone toolmaking, and meat eating—still seemed to emerge in our earliest Homo ancestors around 2.3–2.5 million years ago.

But recent finds contradict those links. In 2010, a startling announcement was made: Two bones with stone-tool butchery marks dated to 3.4 million years ago had been found at the Dikika site in Ethiopia, pushing the earliest traces of meat eating nearly a million years earlier than previously known. This was also far earlier than the earliest Homo fossils. Did this mean Australopithecus could use, and maybe even make, stone tools?

Among other things, critics noted that no stone tools had been found at Dikika. So perhaps Australopithecus wasn’t actually making tools, but just picking up naturally sharp rocks to use as stone knives. However, in May 2015, 3.3-million-year-old stone tools from the Lomekwi 3 site, in Kenya, were announced, pushing back the origin of stone toolmaking by 700,000 years. Just two months earlier, in March 2015, a 2.8-million-year-old fossil mandible and teeth from the Ledi-Geraru research area, in Ethiopia, had pushed the origin of our genus back about 500,000 years. These fossils have not been assigned to a particular species of early Homo, but it is now well accepted that they are the earliest fossils of our genus.

The current evidence points to toolmaking and meat eating occurring by 3.3 million years ago, but only a handful of sites with stone tools and/or butchered animal bones have been found before about 1.8 million years ago. The earliest site with evidence that early humans repeatedly returned to one place to make stone tools and butcher animals, a site in Kenya known as Kanjera South, is dated to 2.0 million years ago; this seems to be the beginning of consistent butchery activities.

So now the evidence for making and using tools dates back to half a million years before the origin of our genus. Making tools almost certainly helped toolmakers survive. Toolmaking would have facilitated access to a wider range of foods and the ability to process those foods more intensively or efficiently, likely making them more palatable and yielding more calories. In the case of meat and marrow eating, toolmaking would have opened up new sources of food higher in protein, fat, and calories than many other foods available in African savanna landscapes.

Given these benefits, could stone toolmaking be a behavior more common in our evolutionary history than we thought, and not something that only emerged with our genus? Chimpanzees use stone tools to crack open nuts and even make wooden spears to hunt smaller primates called bush babies, suggesting that the capacity to make and use tools is rooted deep in our evolutionary history. Still, chimpanzees don’t use tools to make other tools, as early humans did when they created the first stone knives. They also don’t eat animals larger than themselves; their favorite prey are colobus monkeys, which are much smaller than they are. The earliest butchery marks are on the bones of extinct animals that were similar to today’s wildebeests and zebras, which were much bigger than the Australopithecus individuals having them for dinner.

Read more from the archives: “Raw Deal.”

So, what does all this tell us about the idea that Homo was the first maker of stone tools?

Scientists construct hypotheses based on available evidence and then test those hypotheses by gathering additional evidence. The long-standing hypothesis that only our genus was capable of making and/or using stone tools to butcher large animals seems to have been refuted by the recent finds of stone tools at Lomekwi and butchered bones at Dikika—at least for now—since the oldest Homo fossils are half a million years younger than the tools and butchered bones. Perhaps continued field research in sediments dating to around 3.0–3.5 million years ago will turn up Homo fossils, and then the hypothesis will again be supported. (The absence of Homo fossils from this time period is not necessarily evidence of their absence.)

Bernard Wood of George Washington University says that “a convincing hypothesis for the origin of Homo remains elusive,” and argues that Homo habilis should be classified neither as Homo or Australopithecus, but in its own genus. A recent review of the evolution of early Homo suggests that anatomical, physiological, and behavioral traits long held to define our genus did not arise in a single integrated package, but instead emerged over about a million years in three distinct lineages, with some traits evolving earlier and some later. In any case, it has become clear with more evidence that the origin of our genus remains murky, and that Homo may not have been the earliest toolmaker and meat eater in our family tree.