The Denisovans have long been one of the most elusive ancient human cousins, until now. In May 2019, scientists revealed the first fossil evidence of Denisovans outside of the Denisova Cave in Siberia. As the historical human family tree grows, what are we learning about why we’re the only ones left? In this episode, we pose this question to science journalist Carl Zimmer, a columnist for The New York Times and the author of 13 books. Follow him on Twitter @carlzimmer.

We also speak with archaeologist Anna Goldfield about Neanderthals, another close ancient cousin. Goldfield is a columnist at SAPIENS.org, co-host of The Dirt podcast, and the illustrator of The Neanderthal Child of Roc de Marsal: A Prehistoric Mystery. Follow her on Twitter @AnnaGoldfield.

Learn more about Denisovans and Neanderthals.

SAPIENS: A Podcast for Everything Human is part of the American Anthropological Association Podcast Library.

Jen: Picture this: You’re standing at the mouth of Denisova Cave in central Siberia. It’s not cold, like you might expect. The sun is warm, and there are trees and bushes near the cave’s entrance. Light illuminates the cave floor, entering through a large hole above the atrium. It feels like a cathedral.

[footsteps + echoes]

Jen: You walk inside. There are deep holes in the ground and wooden scaffolding on the sides. This is no cathedral. It’s an archaeological dig site.

Russian archeologists have been coming here since the 1970s to uncover human bones and fossils. But, many of the remains were actually crushed before the archaeologists had arrived. In spite of that, they still found bracelets, stone tools, a fragment of a pinky finger, and, most importantly, teeth.

But here’s the thing: Those teeth and that pinky finger are not quite human. So where did they come from? And who else lived here?

Chip: I’m Chip Colwell.

Jen: And I’m Jen Shannon, and we are your hosts for SAPIENS: A Podcast for Everything Human.

[SAPIENS intro]

Chip: In 2010, scientists made a huge discovery. They extracted DNA from these fossils and discovered they belonged to a formerly unknown distant human cousin of ours. They called them the Denisovans, after the Denisova Cave.

Their findings have dated Denisovans to living between about 40,000 and 400,000 years ago. And although anthropologists have conducted loads of research, we have had little additional physical proof of Denisovans—until very recently. Well, kind of. See, 39 years ago, scientists pulled a mandible out of a Tibetan cave. And this mandible, which is a fancy word for jaw bone, wound up in a museum drawer. Then, in the past few years, it was revisited, tested. And in May 2019, anthropologists declared that the tests had revealed something extraordinary. The mandible belonged to a Denisovan!

[Announcement excerpts]

Cat: The date is May 1st, 2019. A mandible found in Tibet has been confirmed as belonging to an archaic human cousin known as a Denisovan.

Paul: First Siberia, now Tibet. Evidence for ancient human cousin piles up. Four decades ago, a Tibetan monk found a jawbone in a limestone cave. Today scientists say it belonged to an ancient cousin of Homo sapiens.

Cat: First evidence of Denisovans found outside of Denisova Cave.

[return to Jen and Chip]

Jen: When it comes to understanding ancient human evolution, we’re living in a new age of discovery. There was a time when we used to think it was just us. Then, we thought it was just us and the Neanderthals. But now, who knows how many human cousins we had back then?

Chip: It’s a good question, Jen. And actually, Carl Zimmer might know. Listeners may remember Carl from season 1 of this podcast. I spoke with him about his latest book, She Has Her Mother’s Laugh, which is all about DNA and heredity. Since that appearance, Carl has reported in The New York Times on a string of really, really exciting developments in the field of early human evolution, including the Denisovan mandible earlier this year.

[phone ringing]

Carl: Carl Zimmer—

Chip: hi!

Carl: Hi, this Chip?

Chip: Carl joined us from the backyard of his home in Connecticut, where the sun was shining and the birds were chirping.

OK, Carl, so to better understand what we know about who these Denisovans were, we invited you back to play a game with us. We’re going to call it Speed Carbon Dating. My co-host Jen will be playing the role of a Homo sapiens.

Jen: It’s the role I was born to play, Chip.

Chip: And you, Carl, can be the Denisovan.

Carl: All right, I will try to play the part of the Denisovan as best as I can.

Chip: OK, so you two come from different backgrounds, and that’s always hard. Jen, what’s important to you on a first date?

Jen: Well, I like to get to know someone first, and it sometimes helps to loosen up with drinks, so maybe we start there?

Chip: Denisovan Carl, what do you think? Can you even hold a cup?

Carl: I could definitely hold a cup. I might not know how to make a cup, but if you gave me one, I could certainly hold it. I’ve got hands that are very agile, good for making stone tools and maybe even doing artwork. So sure, a cup would be no problem at all.

Jen: Well, I don’t know how to make a cup either, and the restaurant will probably have them. So, I think we’re fine. But what kind of place should we go to? Do you have any dietary restrictions, Carl?

Carl: Umm, well, I’ve got gigantic teeth, so certainly eating is not going to be really an issue in terms of grinding up my food. I might not be able to handle some of the food that we eat these days very well, you know, like milk might not agree with me very well.

Jen: What are you, lactose intolerant or something?

Carl: Well, because drinking milk or eating dairy products as an adult is kind of a weird thing to do as a mammal. It’s only been in the past few thousand years that some people have evolved the ability to make the enzymes necessary to break down milk sugar as adults.

Jen: I guess pizza’s out of the question.

Carl: No, no pizza. I would say let’s, you know, if we could eat some venison, I think we’d be great, with berries on the side. We’ll be great.

Jen: Venison with berries? Interesting, I think I actually know a place, but it’s kind of formal.

Chip: Denisovan Carl, do you have formal wear? Actually, do you even wear clothes?

Carl: Maybe. [laughs] I don’t know enough about myself as a Denisovan to say whether I wear clothes or not. Although, I would imagine if you’re in Tibet, if you’re running around naked in Tibet, that’s gonna be a tricky thing. So, I want to say yes, I can make some sort of clothing, maybe simple furs.

Jen: Running naked in Tibet, that sounds like an interesting vacation. And I do love to travel.

Chip: Hmm, Denisovan Carl, we know you’re from Siberia and that you spent time in Tibet, but have you traveled anywhere else?

Carl: I might be able to travel very long distances over water. Yes. And the reason I say that is because people in New Guinea, they have a lot of Denisovan DNA in them. Several percent of their DNA is from Denisovans. There seems to be a special batch of Denisovan DNA that they have that is not found elsewhere.

Jen: Hmm, sounds like a big family.

Carl: And so, some people have just recently suggested that somehow Denisovans got to the island of New Guinea from Southeast Asia. And then that’s where they interbred with modern humans who came to New Guinea. Now, if you’re gonna get to New Guinea, you’re either gonna have to get swept there, maybe clinging to a tree or swept out by a storm, or you’re going out by boat. So that’d be pretty amazing if Denisovans could make boats and sail.

Jen: I don’t know if I’m ready for that kind of vacation. Maybe we can just start slow and see where things go from there?

Chip: It is important to make sure you two are looking for the same things in the long term. Jen, are you hoping to settle down and start a family anytime soon?

Jen: You know, someday down the road, I could see myself having a few kids. It’s important to know if it’s an option.

Chip: Denisovan Carl, just checking, just making sure, would you be able to have children with a Homo sapiens?

Carl: Oh yeah, absolutely.

Chip: Well, Jen, I think we’ve found you a match. Have fun you two crazy kids!

Carl, thanks for playing. In my opinion, you actually make for a pretty great Denisovan.

Carl: Sure, well, you know, you get me started on talking about Denisovans, it’s hard to get me to stop.

Chip: Now that we have a better sense of who these Denisovans are, I want to know more about this Tibetan Plateau discovery. Can you tell us, what’s the broader significance here?

Carl: Well, you know, scientists have been working in Denisova for years now, pulling out more fossils, and a few of them have more Denisovan DNA. So we know that they were actually in this cave at Denisova for a long time. But, you know, there’s no way that an entire population of people could live in one cave. It just doesn’t make sense. And so people have speculated that they must have had a much broader range. And there were clues that that had to be the case, because when scientists looked at the DNA of Denisovans and then compared it to living people, they discovered that there were people in Australia, New Guinea, the Pacific Islands, East Asia, the Americas who had a small percentage of Denisovan DNA in their genomes, so they must descend from Denisovans.

Chip: So, they were definitely interbreeding. And then Neanderthals and humans were interbreeding. Was there a time period—tens of thousands of years ago—where there was, you know, essentially, you have all these different groups that aren’t quite physically the same, but they were probably all intermixing at different times with one another?

Carl: There was a period, yes—maybe between 100,000 and 40,000 years ago—that seems to be the point at which these different kinds of people started coming into contact.

Chip: So, when we’re talking about Neanderthals or Denisovans, we’re talking about our human ancestors?

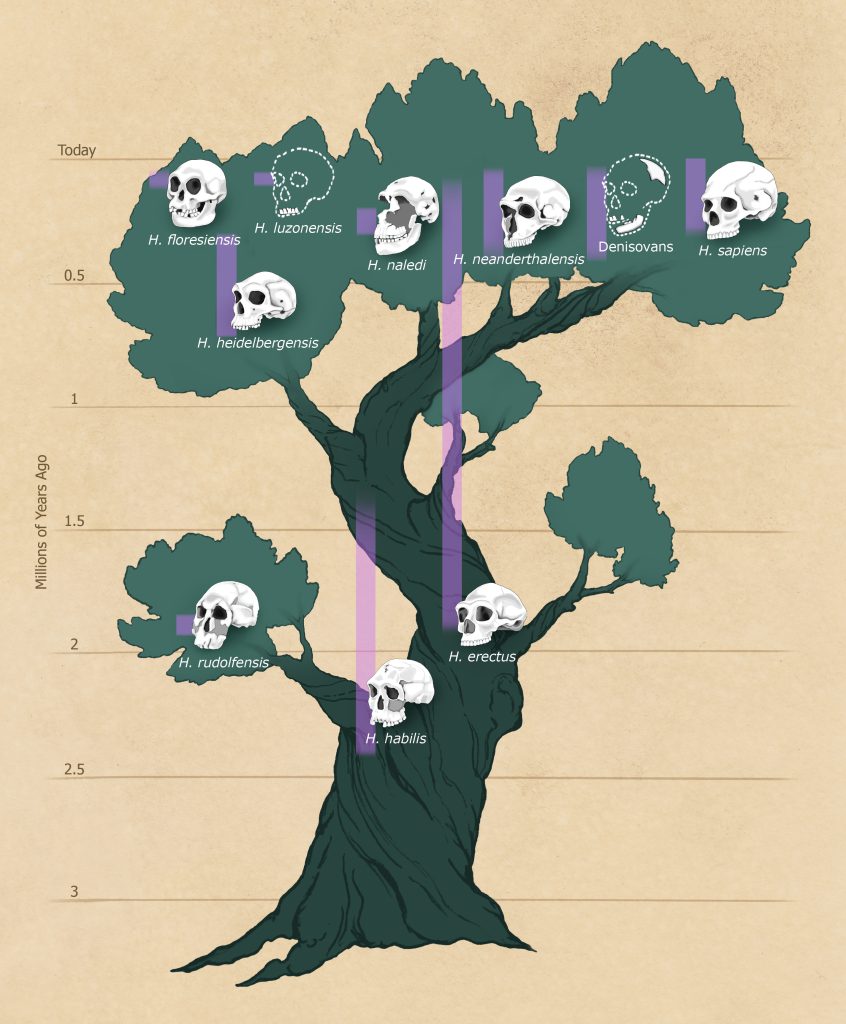

Carl: Yeah, it’s a complicated situation, you know? You have to think about human evolution in different kinds of metaphors. So, on one hand, human evolution, it’s a tree, it’s a family tree: There’s a distinct lineage that split off from our own ancestors, and then that lineage gave rise to both Neanderthals and Denisovans—they split off. So, you have this tree where you have branches splitting into new branches. So thinking of it that way, we’re cousins. But it’s clear that, you know, at some point, some of those very, very distant cousins interbred, and so we are the descendants of that interbreeding.

I think we can think of ourselves as modern humans with some Neanderthal and Denisovan ancestry.

Chip: From the anthropologists that you’ve spoken with, do you have a sense of why finding evidence of Denisovans outside of the Denisova Cave has been so much more challenging than, say, it’s been for finding Neanderthal fossils?

Carl: You know, there’s a good chance that scientists have actually already found a lot of Denisovan fossils—they just don’t realize it. So there could be museum drawers in China and other places in Asia that are full of fossils that look like they might be human or might be Neanderthal or just not quite clear, and no one has quite known what to do with them. And if researchers can analyze them and maybe get some DNA out of them or some protein, they’ll be able to see whether they’re actually Denisovans or not.

Chip: So it’s almost, you don’t know what you’re looking at until you know what you’re looking for.

Carl: That’s right, yeah. And it may be that Denisovan fossils are scattered in places that people have to look for it in new ways. But, you know, I think they’re just catching up.

Chip: Who else is out there? Who do you think is left to be discovered?

Carl: It’s actually an incredibly exciting time to be reporting on human evolution because there are all these humans and human-like relatives popping up all over the place. It wasn’t really that long ago that if you looked at, let’s say, the last million years of human evolution, people tended to talk about it in a fairly simple way, you know, that you had an early species of Homo, our genus, so like Homo erectus, and then, you just start from that single ancestor and then basically go pretty much straight to Homo sapiens. And that was people’s picture of human evolution over the past million years.

But more and more often, people find fossils from the past million years that just don’t fit that. And so there are some really extraordinary finds that are popping up. For example, in the Philippines, there’s an island called Luzon, and in a cave there, scientists have been digging up fossils of several individuals who lived over 50,000 years ago who were a member of our genus Homo but were definitely not Homo sapiens. They have very primitive traits, and they were really small, maybe 3 feet tall or less. I mean just tiny, tiny people, and, you know, they could make tools and so on, and so they’re now called Homo luzonensis.

Chip: So new species, totally new and unknown to us, even just a year ago?

Carl: That’s right. Totally new. And if you go down south a bit to another island in Southeast Asia, an island called Flores in Indonesia, people have found another small human relative called Homo floresiensis.

But it’s different than Homo luzonensis; it has a different set of anatomical traits that set it off as its own species. And then if you go to South Africa, there scientists have been digging up bones from a cave that seemed to belong to some kind of human relative that lived maybe 230,000 years ago or so. So this is after our species has already evolved in Africa. It’s small, and what’s really notable is that it has a very small brain. It’s called Homo naledi.

Some people have sort of jokingly compared it to The Lord of the Rings, where you have this like, past era, where modern humans as we know them shared the planet, and sometimes very closely shared it, with all sorts of different human-like people in this incredible range. So, you have, you know, the Denisovans seem to be these giant bruisers. Then you have Neanderthals, who are a bit shorter but very stocky, and then you have us, the skinny ones. And then you have all sorts of smaller hominins—Homo luzonensis, Homo floresiensis, Homo naledi—all living their own lives. I mean, that’s probably not the end of it. I mean, you know, if all of these species that I just rattled off to you have only been found in recent years, then there’s no reason to think that we’ve found them all.

Chip: In closing, Carl, what does all of this mean? What do these discoveries teach us about ourselves, about being human?

Carl: We’re learning a lot about ourselves. We’re starting to discover that, you know, our genomes contain not just modern human DNA but the DNA from distant relatives who we can’t really see on Earth anymore: Neanderthals, Denisovans, and probably other kinds of vanished people whose fossils have yet to be discovered.

That’s part of who we are. That’s part of what makes us up, and we use their genes today for our health. They’re active in our brains. They’re a part of us. And so, the more we can understand their evolutionary history, the more we’re actually understanding ourselves.

It seems that there were just so many different kinds of humans up until maybe 50,000 or 40,000 years ago, and now there are not. We live on a very uniform planet when it comes to humans. So what happened?

I think people have wondered that for a long time. Now we have all these other kinds of humans in the past million years. And it seems that whenever modern humans showed up, the other ones disappeared. It may not be that we necessarily killed them.

Chip: But something happened.

Carl: Something happened. You know, maybe we just gradually outcompeted them. If that’s the case, what was our edge?

Chip: So we don’t know why we survived and other archaic hominids didn’t?

Carl: We don’t really know. And that would be an interesting thing to understand because maybe it has to do with being incredibly adaptable in terms of living in different environments. We can live anywhere. And that’s our great strength, and, you know, that’s also part of the problem in the sense that today we are rattling the whole planet with potential mass extinction.

Is there a connection between what happened when modern humans encountered other kinds of people and what’s happening today? I don’t know the answer to that, but, you know, I think that we can get some clues if we get to know these other people better.

Jen: It’s so fascinating to think that we’re right in the middle of this evolutionary mystery.

Chip: And, given how new these discoveries are surrounding all of these archaic human cousins, we really don’t have a definitive answer, just the living proof that we are here—and they’re not.

Jen: But, since we do have a lot of established research on Neanderthals, we can at least theorize, why did we out live them?

Chip: Why did the Neanderthals die off and we survived and evolved?

Jen: To answer these questions, I called Anna Goldfield. Anna is an archaeologist who studies the extinction of the Neanderthals. She also writes a column about Neanderthals for SAPIENS.org and hosts an archaeology podcast called The Dirt.

Jen: Hi, Anna.

Anna: Hello.

Jen: So, we’ve been wondering about this question, about 50,000 years ago, there were so many different kinds of human cousins all over the earth, and we’re just wondering, why us? Why did we make it, and they didn’t?

Anna: It’s a really good question, and I can give you at least a theory from the Neanderthal and human perspective.

The thing is, we’re just beginning to become acquainted with all of these new members of our family tree: the Denisovans and Homo luzonensis, Homo floresiensis, but Neanderthals have been, we’ve been aware of them for a lot longer. My dissertation research centered on some of the physiological differences between Homo sapiens and our close relatives the Neanderthals.

And so, a lot of that just comes down to physiology, basically, stockier bodies. They were a lot more muscular, a lot more robust than what we call anatomically modern humans, Homo sapiens. And that uses up a lot of calories, keeping that body working, keeping it warm. And it turns out that to be a Neanderthal takes a couple hundred more calories per day than to be Homo sapiens, and that might not sound like much, but what I found doing my research was I calculated what that meant in terms of food differences over, you know, over a year or over a decade or over a lifetime. And it adds up. One of the things that I did was calculate it in terms of meat, like how many calories is that? What does that mean in terms of reindeer? Like, how many reindeers is that caloric difference?

Jen: OK, so, I have to ask: How many reindeer does it take to sustain a Homo sapiens versus a Homo neanderthalensis?

Anna: Would you like that answer in raw or cooked reindeer?

Jen: Well, do they both cook it?

Anna: Well, that’s the question. We know that certain groups of Neanderthals were using fire at certain times, but then again, in certain other periods, there’s very little evidence for fire in Neanderthal contexts. So first of all, the question becomes, what are they doing if they’re not using fire? Because, actually, it turns out that it’s in the glacial phases, so the much colder, dryer phases, that they’re not using fire, or at least that we don’t have much evidence for fire.

With Homo sapiens, we see a lot more consistent use of fire. When you cook your food, whether it’s meats or starches, you tremendously increase the caloric availability of that food. Basically, cooking is sort of like an external digestion. So cooking meat means that you can get more calories from smaller amounts of meat. And so, if you are cooking your reindeer meat, which it seems like maybe Homo sapiens was doing more, you are getting an extra couple of days’ worth out of one kill.

Jen: It’s like a double whammy: Not only do they need more calories, but they have to expend more calories to eat the meat that’s not cooked.

Anna: Right, exactly. That was what I did my dissertation on, which was the one behavior that I looked at that may have sort of amplified that underlying difference in calorie use between humans and Neanderthals, which is cooking.

Jen: So it sounds like your theory about Neanderthals is that they basically got outcompeted by Homo sapiens, who could do more with less. They could do more of life, living and reproducing with less of the calories, and so they ended up just being more efficient.

Anna: The way the numbers worked out it’s that one reindeer kill, and so I had to estimate the average size of the average Paleolithic reindeer, so it’s really simplified because obviously there are other nutrients in a carcass, but just thinking about the absolute calories, and it would last Homo sapiens about a day and a half longer, possibly two days longer. So, again, these numbers don’t look like much, but if you spin them out over the course of lifetimes or generations, it does end up making a difference.

Jen: So even after a century of research on Neanderthals, we still don’t really know the answer to the question, why us? Why did we make it, and they didn’t?

Anna: It’s a really complex issue, and so it makes sense that we just can’t quite yet unravel it for these other populations. We’re just starting to tease apart the puzzle of what happened, and that’s what’s really exciting about it.

Jen: Wow, that was a lot of information, Chip.

Chip: Yes, it was.

Jen: What did you take away from all of that?

Chip: OK, so big picture: In recent years, we’ve come to discover an ancient human-like cousin of ours called the Denisovans, and the first evidence emerged in Russia. We are now finding evidence of this ancestor in Tibet, and perhaps even farther afield, through fossil evidence as well as DNA. This ancestor of ours lived about 400,000 to 40,000 years ago, somewhere in that range. And I think what we heard here about this discovery that makes it really exciting is how we’re seeing our family tree as like an actual tree, you know, that we’re not seeing one species replace another, but seeing this flowering of all these different people living at different times and different places.

Jen: Well, the thing that really got me about all of those different ancient human cousins is that they were all around at the same time. That whole idea of The Lord of the Rings really stuck with me, nerd alert. Because, I’m just, I have a totally different image of the past now, where there’s all these different kinds of people existing at the same time, and it just really changes how I think about our ancestors.

Chip: Yeah, I’m right there with you. I can’t help but kind of feel like the world was this lonely place before, you know, Homo sapiens came along, and you have these small groups of people eking out an existence and kinda living all alone. But maybe that picture totally needs to be revised and changed.

Jen: Absolutely, with all the interbreeding that everybody keeps talking about. But I have to say, the other thing, too, is that idea of, gosh, if there was this sort of Lord of the Rings–type thing going on, you know, we still have that big question left unanswered, which is, why are we the only ones left around here? Like, how did we end up being the species that endured? And I think that’s a big question that we still have answers left to figure out.

I think the idea of, you know, caloric intake and outcompeting the Neanderthals is one theory, but there were many other ancient humans around at the time, not just the Neanderthals, so I’m still curious to know why us. I think that’s still a great question for science to answer. And I think that’s part of what this kind of research does is, you know, if our idea of the past changes, I think it helps us to think outside the box about what the future can be, and I think our science is only as good as the questions we ask. And when we get these new kinds of research that really open up new ways of thinking, we can ask questions we maybe didn’t even think to ask before. It’s a really exciting time in the field.

Chip: That’s right. And our new view of DNA is allowing us to ask even totally new and really important questions about the human past, right? I’m just so struck by the fact that it now seems that Neanderthal DNA lives on in Homo sapiens but so does Denisovans. So, to think that these ancestors of ours are literally a part of the makeup of who we are as a species is really, really cool.

Jen: So, you might say they’re part of being human.

Chip: That’s right!

[credits]

Jen: This episode of SAPIENS was produced by Cat Jaffee and mixed, audio edited, and sound designed by Jason Paton.

It was hosted by me, Jen Shannon.

Chip: And me, Chip Colwell. SAPIENS is produced by House of Pod with stupendous contributions from our producer Paul Karolyi and intern Freda Kreier, who provided additional support.

Jen: Meral Agish is our fact-checker. Matthew Simonson composed our theme. And a special thanks this time to Carl Zimmer and Anna Goldfield.

Chip: Since this is the age of discovery about archaic humans, we’re covering all of it at SAPIENS.org. So if you want to learn more, subscribe and check out the website. I’m going to put a few links in the show notes.

Jen: This is an editorially independent podcast funded by the Wenner-Gren Foundation, which has provided vital support through Danilyn Rutherford, Maugha Kenny, and its staff, board, and advisory council.

Chip: Additional support was provided by the Imago Mundi Fund at Foundation for the Carolinas.

Jen: Thanks always to Amanda Mascarelli, Daniel Salas, Christine Weeber, Cay Leytham-Powell, and everyone at SAPIENS.org.

Chip: SAPIENS is part of the American Anthropological Association Podcast Library.

Jen: We love anthropology. We love making this podcast, and we hope you love listening to it. If you do, please subscribe wherever you listen to podcasts, and don’t forget to rate us. It helps people discover the podcast and anthropology.

Until next time, be well fellow sapiens!

[return to final portion of the episode]

Chip: So, Jen, did you ever hear back from Denisovan Carl?

Jen: No, I didn’t. I gave him my number and everything.

Chip: Well, I hate to break it to you, but it could be because he’s extinct.

Jen: [laughing] That’s the story I’m telling myself anyway.