Chapter 3

How to Write a Pitch

The pitch provides a unique angle and a small window into the complex whole of your work.

INTRODUCTION

Picture yourself in an elevator.

Suddenly, in steps someone who could turn a story idea you’ve been mulling into something tangible—say, a magazine feature or an online op-ed. As you ascend, you seize your chance to convince this person your idea matters, that it’s fresh and fascinating, that the public needs to know about it now, and you are the one to write it.

There’s no time to ramble. You must intrigue this person before the doors go “ding.”

That is the proverbial elevator pitch. And it’s not so different from pitching editors in the world of public writing, except you’ll probably be on a laptop, not in a lift.

Pitching editors can admittedly be a little nerve-wracking. It’s also a little thrilling. And it’s an excellent opportunity for distilling disorganized thoughts into clear, concise paragraphs that hopefully lead to your byline in your dream publication.

Sometimes a story idea arrives in your mind fully formed, with a narrow focus, a timely news peg, maybe even colorful characters, and an engaging narrative arc. (A news peg is an aspect of a story that makes it newsworthy, such as a connection to a recent political event, popular culture trend, or upcoming holiday.) If that’s the case, feel free to jump to the section below where we show you how to craft a pitch. We’ll also analyze two successful pitches so you can get a feel for the style and what makes a pitch irresistible.

Often, though, you have a seed for a story idea, but you’re not sure which direction to take it or which aspects editors might find most appealing. You might want to write about a certain topic, but you don’t know how to pinpoint the most compelling stories within that subject.

If either of these scenarios is the case, the first part of this chapter will walk you through ways you can hone a hazy notion into a pitch-ready story idea. We’ll pose questions that will help you generate ideas and determine your priorities. And we’ll outline important things to keep in mind if you’d like to pitch an article about your own research, a personal essay, an op-ed, and more.

TURN A TOPIC INTO A STORY ANGLE

One of the most common things editors say when they’re critiquing a pitch is, “This is a topic, not a story. What’s the angle?”

Editors at media publications are not looking for pitches about topics because overviews of topics read like a textbook. A story angle, by contrast, is an intriguing, fresh, specific, and (usually) timely slice of a topic.

For example, “climate change” is a topic. But “a horse breeder in Siberia can’t graze his horses because the melting permafrost is changing the grass” is a story angle. “Rarámuri people of Mexico are renowned ‘superrunners’” is a topic. “Biological anthropologist Daniel Lieberman participated in a 12-hour running ceremony with Rarámuri people to find out what makes a ‘superrunner’” is a story angle.

What made “Chasing the Myths of Mexico’s ‘Superrunners’” more than the topic was the physical and intellectual journey of the anthropologist studying this phenomenon.

Marcos Ferro

If you have a topic you’d like to write about, or maybe a nebulous story idea, here are several strategies you can use to generate pitch-worthy angles:

The heart of a story is a character or group facing conflict and experiencing a narrative arc. (A narrative arc is the path a story takes from beginning to middle to end. In the context of an article, it usually involves circumstances altering people’s perspectives or people taking action to change a situation.) To find fascinating stories within a topic, you can ask yourself several questions:

- Is there an individual or group I can spotlight who is particularly impacted by this topic

- Could I feature a community that is implementing innovative solutions to this issue?

- Do I know about a dramatic or moving incident that encapsulates this subject?

- Can I profile a researcher or group doing something unexpected or investigating something unexplored about this topic to shed light on this area?

- Is there a story from the past that can inform people about this topic now?

For example, anthropologist Brendane A. Tynes wanted to write about the topic of police abolition. So she zeroed in on the story of a mother and daughter who were devastatingly impacted by the criminal punishment system. This approach made her pitch and subsequent SAPIENS essay much more powerful than if she had pitched a topic.

Similarly, anthropologist Karminn C.D. Daytec Yañgot is fascinated by Indigenous peoples’ acts of resistance against destructive development. In her pitch and essay, she highlights one Indigenous community’s novel approach to defending their land: writing down their Oral Traditions.

Trawling TikTok in search of trends related to your favorite topic isn’t necessarily the most efficient way to generate story angles. But if you do notice that a popular culture phenomenon dovetails with your area of expertise or that new ways of thinking are creating seismic shifts in a field, these could be compelling angles. Editors are attracted to stories about trends and shifts in consensus, and these stories can be informative and enlightening for general audiences.

For example, in an essay for Aeon, anthropologist Vivek V. Venkataraman describes young urbanites’ increasing fascination with ancient and contemporary hunter-gatherer societies. Incorporating a range of research studies, Venkataraman adds nuance, context, and counterpoints to this cultural movement.

Evolutionary anthropologist Cecilia Padilla-Iglesias observed that the scientific community once predominantly thought humanity arose in East Africa, but several more recent studies point to a pan-African origin story. In an essay for SAPIENS, she gives nonspecialist audiences a big-picture view of these important shifts in paleoanthropology.

If you’re contemplating pitching a trend story, it’s crucial to conduct research on what has been written before because, by definition, the topic will be popular. Ask yourself: What’s missing from previous articles about this phenomenon? What specific insights can I contribute based on my experiences and expertise? Is there some aspect of this movement that is unexplored or often mischaracterized?

If you dive beneath the surface of every topic, you’ll find numerous questions that people grappling with that topic are trying to answer. Those questions can be the pearls that form fascinating story ideas.

Try writing down your topic and then free-associating questions that fall within that subject. Or rewrite a subject as a question, perhaps incorporating that favorite word of little kids: why?

For example, medical anthropologist Gideon Lasco reframed the topic “negative perceptions of drug use” as an essay that answers the question, “Why Are People Who Use Illegal Drugs Demonized?”

As another example, the topic “environmental carcinogens” could be retooled as “Is the Developed World We’ve Created Giving Us Cancer?,” an essay that cultural anthropologist Chelsey Kivland wrote for The Conversation.

Question-based articles can be evergreen, or timeless. However, you’re more likely to pitch these ideas successfully if you link them to current events, a holiday/anniversary, or a trend. For example, anthropologist Dimitris Xygalatas, whose research centers on the topic of rituals, devised an article pegged to the December holiday season that asks, “What’s the Point of Holiday Gifts?”

Some outlets publish listicles—articles in the form of a list. These are typically overview stories that divide a topic into easily digestible bites, making it more fun and appealing. The topic “the archaeology of wine” is a little on the dry side. But turn it into “Five Turning Points in the Evolution of Wine,” and it suddenly sparkles.

As with other stories, you’re more likely to successfully pitch listicles if you peg your idea to a news event, pop culture trend, or upcoming holiday, like “Five Solstice Sites That Aren’t Stonehenge.”

Need a few more examples of the difference between a topic and a story?

- Topic: Museums are important places for scientific discoveries.

- Story: A 40,000-year-old human fossil long stored in a museum is now providing important, new insights into early human cultures.

- Read on: “Learning From Snapshots of Lost Fossils”

- Topic: The conservation of large wild mammals raises thorny ethical concerns.

- Story: At a breeding center in Portugal, conservationists navigate many ethical questions to make the Iberian lynx “‘the greatest recovery of a cat species ever achieved through conservation.’”

- Read on: “Bringing Back the World’s Most Endangered Cat”

- Topic: Invectives in the English language are often gendered insults about women.

- Story: An anthropology teacher asks her students to insult one another in order to elucidate how swear words are gendered as feminine.

- Read on: “Why I Ask My Students to Swear in Class”

- Topic: When people or their children who live outside social norms die, their remains can haunt the living.

- Story: An anthropologist traveling the Irish countryside comes across a mysterious memorial and unravels the history of unmarked burial sites and why they matter to the living.

- Read on: “Buried in the Shadows, Ireland’s Unconsecrated Dead”

WRITE ABOUT YOUR RESEARCH AND EXPERIENCES

TIPS FOR WRITING PITCHES

Your writing style should feel journalistic, not academic. That means avoiding jargon and references to academic theories. Use active rather than passive voice. Make your sentences as straightforward and punchy as possible. And choose dynamic verbs that generate momentum and energize your pitches with excitement.

Your tone should mirror the tone of your proposed article. If your topic is fun and light, be playful and humorous. If it’s serious and dark, use powerful and chilling language.

Your voice should match the voice of your target publication. Most general science and news publications have broadly similar voices. If you’re pitching an outlet focused on health or business or a niche topic, it’s a good idea to adopt the style of that publication and emphasize the aspects of your idea that are most relevant to their audience.

Vivid description is great, but make sure every detail is there for a reason. Extraneous information bogs down a pitch and can make your editor’s eyes glaze over.

Many publications—including Scientific American, The Conversation, SAPIENS, and various newspapers—encourage researchers to write about their own work. It’s a great way to shape public thinking or policy, give back to the communities you work with, and share your ideas with broader audiences. It can also be an opportunity to get creative and to write from your heart as well as your head.

It also presents challenges. Because you’re so close to your work, it can be difficult to know which aspects would be most interesting and relevant to general audiences. It can also be challenging to transform data analysis into a story and determine how personal (or not) to get.

To brainstorm story angles based on your research, you can use any of the strategies in the section above (look for trends, focus on characters, et cetera). You can also ask yourself:

- Which aspect(s) of my research makes me especially hopeful, angry, shocked, confused, or enthusiastic? Could I turn that feeling into an inspiring solutions story, an impassioned op-ed, or an investigation that attempts to answer a question?

- Is there a story involving an individual or a community I worked with that particularly moved me or changed my thinking?

- Is my research connected to another group’s quest to address a similar problem or shed light on an analogous mystery

- Does my research offer a fresh and unexpected perspective on a newsy topic?

- Is there a personal reason that’s motivating me to do my work that I could describe in a personal essay?

If you have many things you want to say about your research but don’t know how to fit them into one story, that’s great. Don’t. Turn your ideas into several articles, each with a specific angle and length.

Environmental anthropologist Sophie Chao has produced a rich repertoire of stories inspired by her fieldwork with the Marind people, whose land in Indonesian-controlled West Papua is being destroyed for industrial oil palm farming. In SAPIENS, she exposes the problems of “sustainable” palm oil and the repercussions of deforestation on wild animals. For Sydney Business Insights, she describes how the palm oil industry has altered traditional diets. For Aeon, she meditates on Marind mourning rituals for people and ecosystems.

If you’re still having trouble narrowing down your focus, remember what editors care most about: What is new about this story? What is timely about this idea? Why would it be relevant and interesting to readers? Then zero in on the most current, fresh, and widely relatable or applicable aspects of your research.

If you have a research article coming out, that’s a great news peg. But keep in mind that few research papers get covered by major media outlets unless the results represent a massive breakthrough or are irresistibly bizarre. And single-paper stories are often written by staff writers or editors rather than freelancers. In most cases, research articles focus on such narrow parameters that they move their fields forward with the speed of an inchworm.

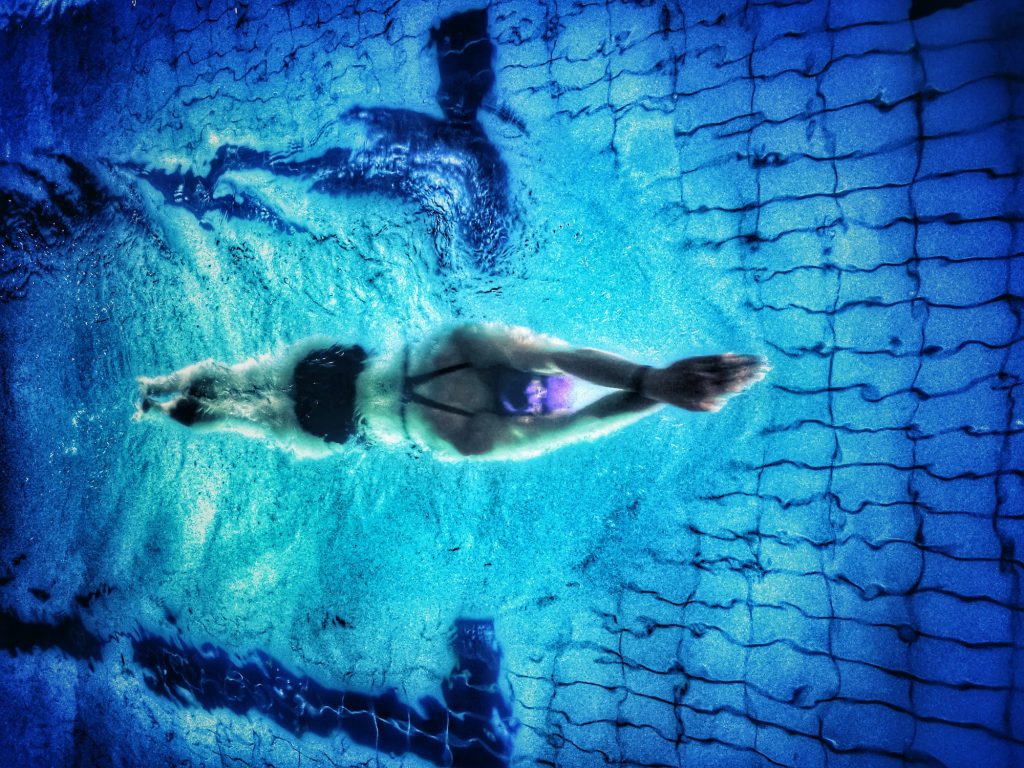

Most likely, you’ll have to pitch your article as the news hook for a story that makes a broader point. For example, biological anthropologists Cara Ocobock and Sarah Lacy wrote a cover story for Scientific American disproving the notion that men evolved to hunt while women evolved to gather. The article cites their own recently published research as well as a wealth of evidence from other studies.

You’ll also need to situate your study within larger contexts—current events and other research in your area—to convey to editors why it matters to broad audiences. In a Washington Post op-ed, for instance, biological anthropologist Kate Clancy explains why the medical establishment ignored women’s widespread reports of unusual menstruation after receiving COVID-19 vaccines.

If you’d like to write a personal essay about your research or other life experiences, your pitch should focus on the takeaway messages that would be relevant to readers. One of the most common reasons personal essay pitches are rejected is because the insights are mainly applicable to the writer, not general audiences. With a personal essay, the writer should be a window, not the view. Their perspective should be the lens people look through to see an issue in a new way.

For example, anthropologist Christine Chalifoux shares her experience of widespread anti-Asian racism during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic as a springboard to reflect on her fraught experiences growing up as a Korean American transracial adoptee.

WRITING OP-EDS AND COUNTERPOINTS

In “Between Male and Female,” Molly Bearman argues that new television shows could push forensic anthropologists—and the rest of us—to rethink our categories of biological sex.

Collection of the Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University; 2006.070.020.

If something about the world is upsetting you and you have an idea for how to fix it, your frustration could fuel an opinion-based essay, or op-ed. These are typically short (600- to 900-word) pieces that take a strong stance on an issue and offer potential ways to improve the situation.

As with trend stories, op-eds typically revolve around a timely and well-known topic. So it’s vital to determine what’s been written before and find a new angle. Ask yourself: How original is my take on this problem and its potential solutions? Why am I the right person to write this story? How do my experiences and expertise allow me to offer new insights on this issue?

Some publications have a department devoted to opinion pieces, and sometimes these outlets require writers to submit the full op-ed rather than a pitch. So it’s important to know in advance if you want to publish an op-ed versus another kind of essay.

In “Stop Erasing Transgender Stories From History,” Gabby Omoni Hartemann argues for a historical perspective on sex and gender.

University of Liverpool/Flickr

Often writers can present an op-ed that is structured like an essay or write an essay that offers an opinion.

For example, let’s say you’d like to write about gender identities. You could write an op-ed like “Stop Erasing Transgender Stories From History” or “Biological Science Rejects the Sex Binary, and That’s Good for Humanity.” Alternatively, you could write an essay that clearly presents a view but does so in a more exploratory way. Examples include this commentary on gender portrayals in TV shows, this invitation to eliminate gendered pronouns from the English language, and this personal essay on ancient clay figures that depict nonbinary identities.

However, when you’re first starting out, it’s best to have a clear view of your goals and the genre (op-ed versus essay) that will best fulfill them. That’s because when you’re pitching an editor, it can be challenging to convey the nuances of an article that doesn’t fall neatly into the op-ed or essay section. Editors will often advise you if they think your pitch would be better suited to a different department. But they also might reject your idea if they’re not sure how to categorize it.

DECIDE WHICH PUBLICATION TO PITCH

Outlets that Publish Anthropologists

Aeon (essays)

Africa Is a Country (essays)

Alea Magazine (essays and more)

Allegra Lab (essays)

Babel (essays)

Boston Review (essays/book reviews)

The Chronicle of Higher Education (essays/reporting/op-eds/advice)

The Conversation (essays/explainers)

CounterPunch (essays/op-eds)

Creative Nonfiction (essays)

Discover magazine (essays)

Emergence Magazine (essays/op-eds/poetry/films/audio)

HuffPost (essays/op-eds)

Inside Higher Ed (op-eds/letters to the editor)

The Intercept (investigative essays)

Literary Hub (essays)

Narratively (essays)

The Nation (essays/commentary)

Nautilus (essays)

Newspapers, local and national (op-eds)

Orion magazine (essays)

Otherwise (essays/poetry/fiction/visual/sound)

Public Books (essays)

SAPIENS (essays/op-eds/visual/poetry)

Scientific American (essays/op-eds)

Slate (essays/op-eds)

Teen Vogue (essays/op-eds)

Undark (essays/op-eds)

Vox (essays/explainers)

Once you’ve formulated your story idea, determine which outlet(s) you’d like to pitch.

The best way to do this is to read various publications to get a sense of which ones publish articles that match the subject, length, tone, style, and format of the one you’d like to write. Editors are looking for versions of the story types they’ve already published. You’ll almost never be the first op-ed in an essay-driven magazine, for instance.

Next, read the publication’s submission guidelines before you start writing your pitch. Outlets look for broadly similar qualities in a pitch, but each one has different procedures and preferences that will impact what elements you include in your pitch.

Remember that rejections are common, so it’s a good idea to have a few publications in mind and to start with your first choice and then move down the list as needed.

Don’t simultaneously pitch the same story idea to multiple publications unless it’s breaking news that needs to be published immediately, and you inform each editor that you’re pitching other outlets. Instead, send one pitch and wait for the editor to respond. It’s fine to check in with the editor if you haven’t heard back after two weeks.

If your pitch is time sensitive, add “time sensitive” to the subject line, and feel free to state in the pitch that if you don’t hear back from a certain date, you’ll submit your pitch elsewhere.

One final note. If you are an undergraduate student, it is rare for major outlets (SAPIENS included) to publish your work. Look for lists of outlets that specifically welcome your contribution. Build a portfolio of published pieces that can demonstrate to future editors that you have the skills to successfully work with them.

HOW TO WRITE A PITCH

The first thing to remember is: Always keep your reader in mind.

For a pitch, your reader is an editor—a person who is constantly drowning in hundreds of emails, pitches, articles, and assignments. It’s essential to capture their attention immediately and convey your idea quickly and clearly.

There are many ways to do this, but most successful pitches include the following elements:

If the publication asks writers to email their pitch, the first thing the editor will see is your subject line; it should be a catchy title that clearly encapsulates your idea. Typically, editors prefer the subject line of an email to begin with “Pitch” (or “Freelancer Pitch” or “Anthropologist Pitch” to distinguish it from pitches from public relations organizations), followed by a title.

Hint: Look at the publication’s article titles and model your title after their style (note that print and online titles may differ). So your subject line could read “Anthropologist Pitch: What Indiana Jones Gets Right About Archaeology” or “Freelancer Pitch: What’s the Appeal of Deep Voices in Men?”

If the publication asks writers to pitch through Submittable or another online platform, they may ask for a potential title. Even if they don’t, some editors recommend including a title/headline and even a subhead in the body of a pitch, since these can help the editor understand your main point and visualize your idea as it would look on the page.

(A subhead, subheading, tagline, or dek, in journalism-speak, is the brief text that appears immediately under the headline and offers intriguing information that sums up the article.)

Effective pitches usually begin with a compelling story, an evocative scene, or a surprising statement. This paragraph typically consists of two or three sentences that go straight to the heart of the story you want to tell.

If your story is about a cultural phenomenon, this paragraph might capture the colorful details of that movement, the people involved, or a specific incident that represents the phenomenon. If it’s about a quest to solve a mystery, you might portray a scene where someone is searching for evidence. Or you might pull back and offer a sweeping description of the mystery itself. If it’s about a unique solution to a problem, you might describe some of the methods your main characters are using to tackle the issue.

Now that you’ve captured the editor’s attention, it’s time to outline the practical details: why your idea matters, why it’s important now, and why you’re in a good position to write about it. Then you’ll briefly explain how you intend to write the story.

There are several ways to convey why your idea matters. If it’s about a solution to a problem, you might explain the consequences and why previous efforts to ameliorate the issue have been unsuccessful. If it’s about a recent finding, you could discuss how the research could shape people’s thinking in new ways or why it’s important to certain communities. If you’re commenting on a cultural phenomenon, you could illustrate how it illuminates certain aspects of the human condition.

If your story is about something widely understood, like climate change, you don’t need to provide background information. If it’s not, you may need to incorporate an illuminating statistic and historical or scientific context to show why the issue is significant. Make this information as brief and colorful as possible. The editor doesn’t need to completely understand the issue; they just need to understand it enough to know why it’s important.

Editors also want to know why a story should be written now. To emphasize this, you might highlight a new paper coming out on the topic or connect your idea to current events, an upcoming holiday, or a pop culture trend. Don’t worry if your story doesn’t have a “now” element; many excellent stories are evergreen, though they still need to be relevant and important to people’s lives today.

Somewhere in these paragraphs, you’ll want to mention your relevant expertise and experiences. Many people may be uncomfortable “selling” themselves. But rest assured, a subtle statement is sufficient. For example, “As an anthropologist who studies X, I have interviewed many people about Y.” Or “In addition to working as a resource manager in A, I volunteer with an organization focused on B.” Or “I am an archaeologist who lives in X location and have seen how Y issue impacts the community.” If you’ve previously written for the public, include a sentence that mentions and links to those articles.

Finally, if it’s not already clear, it’s helpful to tell the editor how you plan to execute the article. You might explain that you’ll weave together quotes from your sources (interviewees) with observations from your fieldwork. You could list some examples you plan to provide in your article to prove your main point. You could also discuss who is responsible and who is impacted by the phenomenon you’re writing about, as well as who you might interview.

EXAMPLES OF SUCCESSFUL PITCHES

Let’s take a closer look at two pitches we received at SAPIENS. As you scroll over the text, our commentary will appear, shedding light on why each element was effective.

Pitch 1

Bettmann /Getty Images

The first pitch came from archaeologist Maria O’Donovan and later became the story “Digging Up Woodstock.”

Email Subject: Archaeologists dig up secrets from Woodstock for its 50th anniversary

On a cloudy morning in October 2017, I found myself on a hillside in Bethel, New York, thinking about the most efficient way to remove leaves that covered the hill’s rocky surface. Below the wooded hill was the open, grassy field where, 50 years ago, around half a million young people came together for “three days of peace and music” in one of the defining events of their generation.

This paragraph subtly but effectively transports the reader to Woodstock as an excavation site, which is the crux of what this story is about. It establishes the writer as a participant in the excavation. It emphasizes the news peg: the 50th anniversary. And it conveys the importance of the festival to the public.

I and other archaeologists from the Public Archaeology Facility at Binghamton University were beginning a project at the site of the Woodstock Music and Art Fair. Our team was there at the request of the Museum at Bethel Woods, which is the custodian of the 1969 festival site and preserves and interprets the legacy of the 1960s and the festival’s spirit. Archaeology—surprisingly to some—has played a small but vital role in these efforts.

Here O’Donovan establishes why she is the right person to write this article. Then she draws attention to the fact that many people would be surprised to learn that archaeologists are investigating Woodstock. Editors are always looking for something unexpected that makes readers say, “Wow, I would never have thought that.”

The concert itself is infamous for being messy and disorganized: The organizers of the festival stopped bothering to collect tickets after the fences came down, and the crowd grew to many times what they were expecting or able to handle. Amid the chaos, no one paid attention to the exact position of the stage or vendor locations. At the best of times, people’s memories are faulty; for drug-fueled Woodstock, one of the common jokes is that if you remember it, you weren’t there. Archaeology can help fill these gaps.

Here the writer explains why this story matters by describing a dilemma and illustrating that archaeologists can help resolve it. Her tone is light and fun, which is fitting for a story about Woodstock.

In this 2,000-word essay, I will show readers how and why archaeology is important, even for contemporary events documented by photos and writing. I will walk readers through the process of how we excavated the site and shine a spotlight on the things we found. The essay will cover practical issues of preservation planning, along with bigger issues of heritage meaning. This work shows how archaeologists have a unique, material take on the world based on the things people use and discard every day.

In this paragraph, she lays out her plan for the essay, letting the editor know what information she will include. She also offers a big-picture takeaway about the meaning of heritage and the importance of archaeologists and the material they study. This lends gravitas to the story and makes it feel like it goes beyond one place and time period.

Pitch 2

Heart rules/Pexels

Now let’s analyze this pitch by biological anthropologist Cara Ocobock, which eventually became the essay “Sex in Sport: Men Don’t Always Have the Advantage.”

Email Subject: Do Men Always Have Advantage Over Women in Sports?

BZZZZZ. BZZZZZ. My phone vibrates on the table next to me, notifying me of an email from a student. I swipe it open. “DR. OCOBOCK, WE JUST TALKED ABOUT THIS!!!” Below that message was a series of Instagram and TikTok posts revealing the extreme disparity in the weightlifting equipment and meals supplied to the NCAA women’s and men’s March Madness basketball teams. The men’s meals looked wholesome, and their gym was stocked with squat racks, benches, barbells, and free weights. The women’s meals looked anemic, and their gym consisted of a single rack of small dumbbells.

Ocobock’s beginning buzzes like an alarm bell in the reader’s mind, and the alarm keeps ringing as she describes the striking inequalities between the treatment of men’s and women’s basketball teams. It’s an intriguing anecdote that riles up the reader. It also subtly but clearly hints that this issue is newsy, since the information is all over social media.

This came right off the heels of asking my anthropology of sports students to take pictures of their gyms to assess equipment disparities between the men’s and women’s dorms. Much to the surprise of my students, many of whom were skeptical that sexism still existed in sports, the difference was stark, mirroring the aforementioned social media posts.

Here the author seamlessly integrates her expertise as a teacher and anthropologist. She also conveys that this issue is surprising, since many of her students were under the impression that U.S. society had moved beyond sexism in sports. An unexpected, persistent injustice hiding in plain sight is catnip to editors.

The recent NCAA debacle is just one of the innumerable examples of sexism in sports, shining a harsh light on a problem that many in the public thought to be a thing of the past. The way women’s sports and women athletes are treated is a problem that intersects sex, gender, and race. Furthermore, the justifications for this treatment are as much grounded in falsehoods and misunderstandings about biology and athletic performance as they are in our problematic sexist, racist, and genderist past. One need not look far to find recent stories about the Olympic Committee’s mishandling of intersex athletes—imposing scientifically unfounded regulations on women, particularly women from the Global South, including Caster Semenya.

Ocobock now zooms out to illustrate that this problem is widespread and tangled with other issues, including racism. By mentioning that these prejudices are rooted in falsehoods, she implies she’s going to expose and challenge these untruths. Debunking myths is critical for social justice, and it tends to be interesting to both journalistic editors and general audiences.

Drawing on biological anthropology, anthropology of sports, and cultural anthropology, I will present a brief history of sexism and genderism (which intersects with racism) in sports, as well as name and correct myths and misconceptions that fuel the unacceptable behaviors and policies we are witnessing in action. As the NCAA story unfolds and the 2021 (formerly 2020) Summer Olympics approach, these topics will be at the forefront of national and international discourse.

Finally, the author underscores that this story will contribute to popular conversations around the world because it’s so timely. She also gives the editor an idea of how she will approach the article, combining elements of anthropology and history with correcting widely held misconceptions.

Activities

Prepare to Pitch

-

Pitch analysis activity

The Open Notebook, a resource for journalists who write about science, has compiled a database of successful pitches. Look through the examples and find a pitch that resonates with you. Analyze why you’re drawn to it and which aspects were effective and why. You can also look at a pitch that doesn’t appeal to you and ask yourself which parts made you lose interest and why.

-

Reverse-pitch activity

Pick a published article you enjoy and try reverse engineering a pitch from it. You might find that, just like a pitch, the article begins with a story, scene, or surprising statement and then moves on to a paragraph that illustrates why the issue is important now. Many of the elements that make a pitch effective also make an article effective.

-

Writing activity

Draft a pitch for your story idea. Remember this general format: Open with a brief story or scene. Say what you want to write and who you are. Convey why your story matters right now, what your narrative is, who the characters are (if relevant), and (if it’s an op-ed) your main points.

After you’ve finished writing, read the pitch aloud, either to yourself or another person. Does it have momentum throughout, or are there parts where you can feel your voice dragging? If so, condense that part and/or use more impactful and exciting words.