Chapter 7

Habits of Thriving Public Anthropologists

Climb the last steps of public writing: continue to grow yourself upwards and outwards.

INTRODUCTION

Now that you’re strengthening your skills at pitching and writing compelling stories, you’re well on your way to becoming a confident public writer.

In this final chapter, we’ll focus on habits and practices for cultivating a thriving writing life. We’ll offer a bevy of tips on writing efficiently, overcoming writer’s block, staying organized, and building a supportive community.

FIND WHAT WORKS (AND FEELS GOOD) FOR YOU

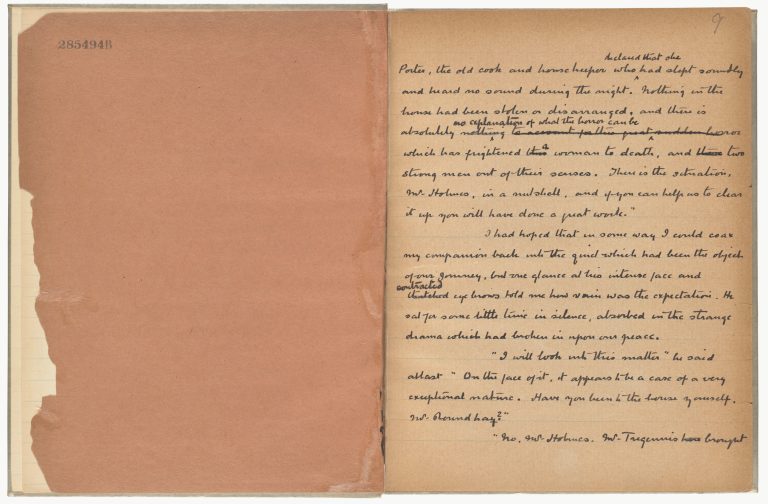

Sir Arthur Doyle Conan’s draft manuscript of Adventure of the devil’s foot, reveals his editing process.

In the book Air & Light & Time & Space, Helen Sword explores the habits that make academic writers successful. Do they write in the morning or at night? Every day in small increments or inconsistently in larger chunks of time? In their office, at home, or in the park? Do they outline first or figure it out as they go along? Do they blast out a really rough draft in one go, or do they carefully carve each sentence like Michelangelo on marble?

The answer, Sword concludes, is “yes.”

Writers define success in various ways, and the paths they take to achieve that success differ in just as many ways. So there’s no reason to feel guilty if your preferred approach isn’t what some writing guru says it should be.

In this chapter, we’ll offer tips that work for a variety of people. But ultimately, you have to find what works for you—and what helps you enjoy the process. Some aspects of writing can be a drag, but others can be fun, inspiring, and nourishing. Sword encourages writers to find “that sweet spot where productivity and pleasure meet.” That might mean setting up a space in a beautiful nook with a view, writing at midnight or 5 a.m. when your home is quiet, or playing a piece of music on repeat to get you in the zone.

Whichever approach you choose, it may have to change over time as your schedule and lifestyle fluctuates.

WRITE FIRST, EDIT LATER, AND “TK” FOR THE WIN

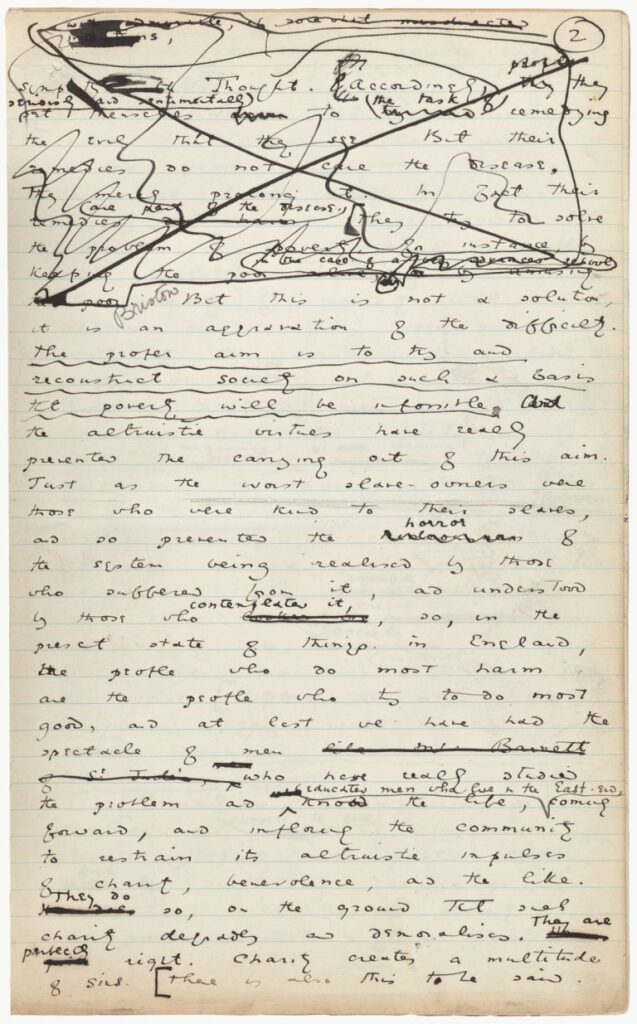

Oscar Wilde heavily edited his 1891 essay, “The Soul of Man Under Socialism.”

A common edict in writing is: “Don’t edit while you write.”

Most people find that they’re more efficient—by leaps and bounds—if they write an essay first, then edit it later. The main reason is that if you write continuously without editing or stopping to research something, you are more likely to enter what psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi called “flow.” (By the way, if you want to talk about this at happy hour, his name is pronounced ME-high Cheek-SENT-me-high, and just saying it induces a flow state.)

When you’re in flow, you’re completely absorbed in a task, time seems to evaporate, and the work feels rewarding. By contrast, if you’re constantly stopping to critique your paragraphs, Google information, consult your research notes, and check your interview transcriptions, writing can feel like a chore. You also increase the likelihood of getting distracted and diving down internet rabbit holes.

One of our editors spent a week in a Mars habitat simulation with no internet and had to write an essay. She couldn’t fathom how she could write a research-heavy piece without Googling anything. The surprise? She never wrote anything so fast in her life. And it was pretty darn good.

Some writers even write by hand because it can help thoughts flow better. Inside scoop: These training modules were first drafted by hand and then read aloud into an AI transcription service.

Another benefit of writing off the top of your head is that the information that naturally rises to the top of your head is what you find most interesting, moving, and important. Which is great because that’s the information you want in your essays.

You may be wondering, But what if I forget things when I’m writing off the top of my head?

“TK” can come to the rescue. It’s an abbreviation in journalism that means “to come.” You might see your editors use it. And you can use it for everything from a statistic you can’t recall (“participants experienced a TK percent increase in well-being”) to entire sentences (“TK, TK, TK that really cool quote from that woman at that conference”). With TK in hand, you can write more quickly and add the forgotten details later.

If you adopt the “write first, edit later” habit, your experience is more likely to be enjoyable, lower effort, and efficient. But there’s one thing you have to come to terms with: When you’re ready to edit, and you look at this flow-state draft, it may be crap.

And that’s OK.

EMBRACE THE SHITTY FIRST DRAFT

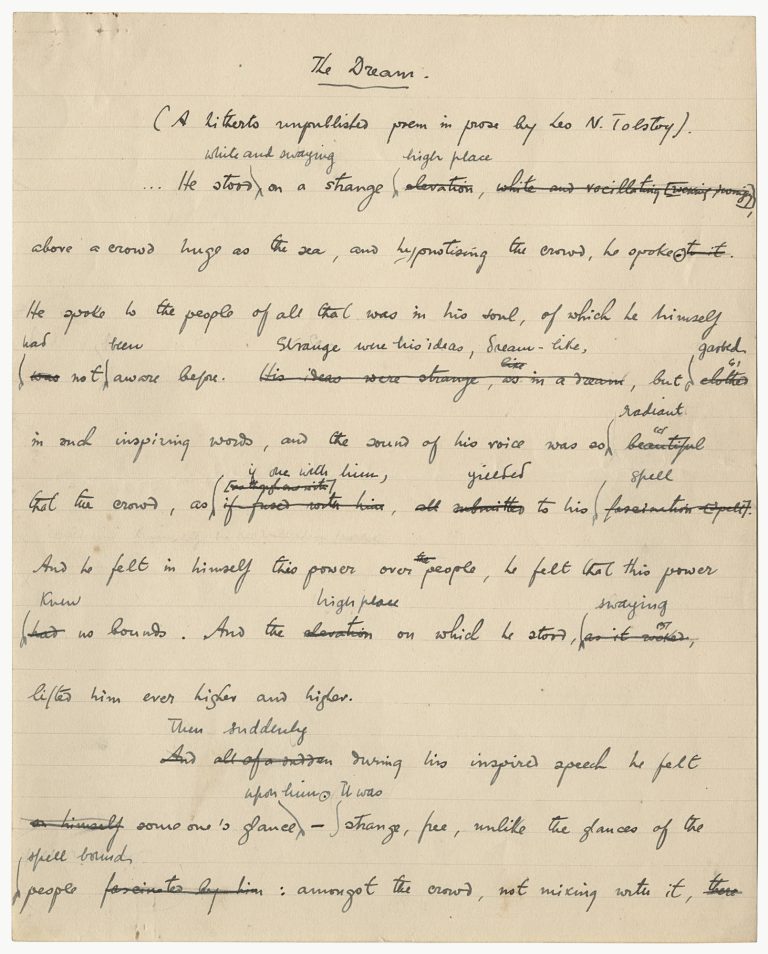

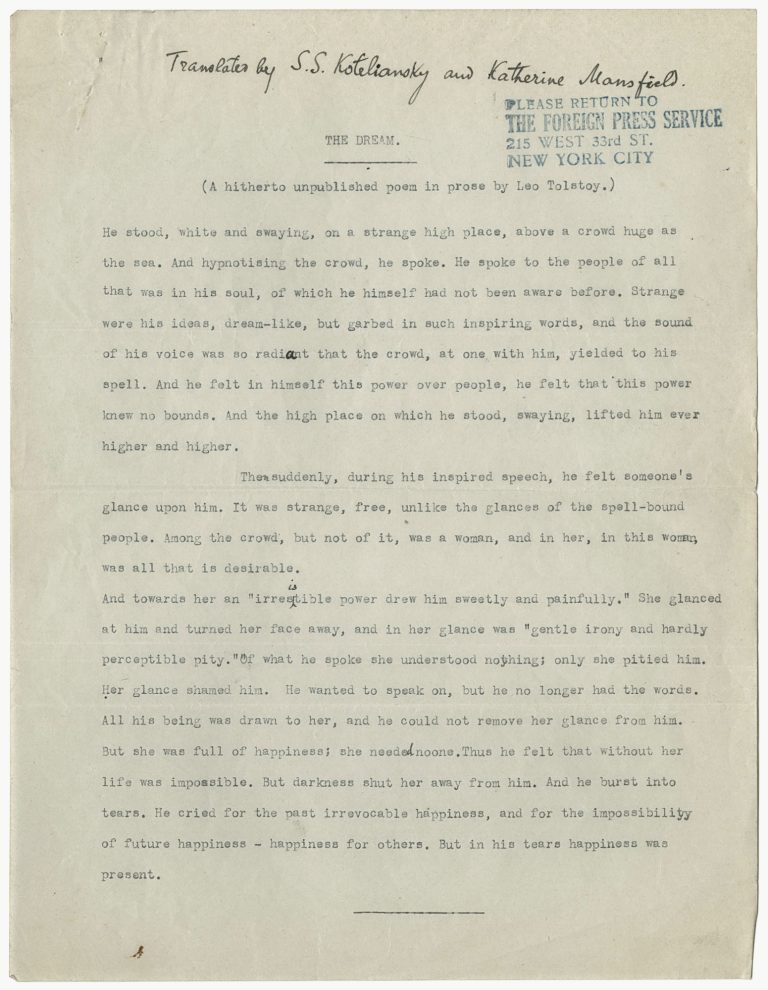

S. S. Koteliansky and Katherine Mansfield drafted by hand their translation of Leo Tolstoy’s poem, The Dream.

Manuscript Collection MS-2663/Harry Ransom Center

Even the typed-up version of Tolstoy’s poem, The Dream, received a close edit, catching final typos.

Manuscript Collection MS-2663/Harry Ransom Center

In her beloved book on writing, Bird by Bird, Anne Lamott introduces the idea of shitty first drafts. “All good writers write them,” she notes. “This is how they end up with good second drafts and terrific third drafts.”

Have you seen the first draft of the “To be or not to be” speech in Hamlet? Frankly, it’s meh. Shakespearean scholars call it the “Bad Quarto.” But by the third draft (or so), it became one of the most famous and poetic speeches of all time. If William Shakespeare wrote shitty first drafts, so can you.

If you expect your first draft to be brilliant, you may become paralyzed by perfectionism, discouraged by the admonishments of your inner critic, and mired in writer’s block. But if you accept that your first draft will inevitably be a steaming pile of manure, you can get the information down with a reasonable amount of confidence and efficiency.

Remember: Manure is the fertilizer that helps your second and third drafts grow.

BANISH WRITER’S BLOCK

As Maya Angelou said, “What I try to do is write. … And it might be just the most boring and awful stuff. But I try. When I’m writing, I write.”

William J. Clinton Presidential Library/Wikimedia

The above methods will help prevent you from alternately staring at a blank page and gazing out the window, then repeatedly making cups of tea and even resorting to cleaning the kitchen. But if you’re still stuck, whether you’re at the first draft stage or you’re editing a draft and can’t quite get something right, here are some other things you can do:

This could be one sentence that eventually goes at the end of the article, a quote that will go in the middle, or half-formed phrases and facts you’ll later cobble together to form a nut graf. Or you could write, “I want to say something like [insert crappy sentence here] that makes some of the following vaguely phrased points: …” That start is better than a blank page.

If all else fails, take Maya Angelou’s approach and write anything that comes to mind. “What I try to do is write,” she says. “I may write for two weeks ‘the cat sat on the mat, that is that, not a rat.’ … And it might be just the most boring and awful stuff. But I try. When I’m writing, I write. And then it’s as if the muse is convinced that I’m serious and says, ‘OK. OK. I’ll come.’”

Sometimes just getting the words out helps, and you can also get feedback. If no one’s around to talk to, talk to your pet. If you don’t have a pet, talk to an imaginary friend.

Sometimes when you feel stuck or blocked, you feel the need to go for a walk or get some fresh air and a new perspective. But an inner voice tells you that that isn’t work, and if you just buckled down, you’d push through your creative blocks.

Here’s how you can respond: “Actually, dear inner voice, a 2014 Stanford University study found that people walking on a treadmill increased their creative output by 60 percent compared with those who were sitting. Another Stanford study concluded that 100 percent of people who walked outside were inspired to think up at least one high-quality, novel analogy in response to a prompt, compared with 50 percent of the people who sat inside. So I’m going for a walk.”

If walking isn’t an option, note that the above study and other research suggest that going outside enhances creativity and focus, even without walking.

In the classic book The Artist’s Way, Julia Cameron popularized the concept of “morning pages”—three pages of longhand, stream-of-consciousness writing. The writing doesn’t need to be artful. In fact, Cameron says it shouldn’t be artful. You can write about being tired or complain about an annoying person. You can remind yourself to change the kitty litter. It doesn’t matter. Your goal is to acknowledge, process, and release the thoughts cluttering your mind.

You can also use this method just before you start writing your article, book chapter, or whatever public writing you’re working on, at whatever time of day. Your goal is to create flow and build momentum. It’s sort of like doing a warm-up before a workout.

In the video for the Florence and the Machine song “Free,” singer Florence Welch has the bespectacled, stern, gray-suited actor Bill Nighy play the role of her anxiety.

Personifying aspects of yourself like this can be a useful exercise. If your inner critic shows up when you don’t want it to, try giving them a name and describing their characteristics on a piece of paper. Julia Cameron describes her inner critic as a snobby, posh Brit named Nigel, which sounds like the perfect role for Bill Nighy.

Once you’ve written a few sentences about your inner critic, fold up that paper, put it in a box or similar container, and place it in a separate room while you allow your writer self to freely create.

Setting a goal to focus on writing for several hours can be intimidating, especially for those of us with short attention spans. Software developer Francesco Cirillo created the Pomodoro Technique to overcome this problem. Using a tomato-shaped kitchen timer (hence pomodoro, Italian for “tomato”), he organized his schedule into 25-minute chunks of focused work separated by 5-minute breaks. After four consecutive intervals, he took longer breaks—usually around 15–30 minutes. Try experimenting with the interval lengths (and kitchen timer) that work best for you.

READ STRATEGICALLY AND WIDELY

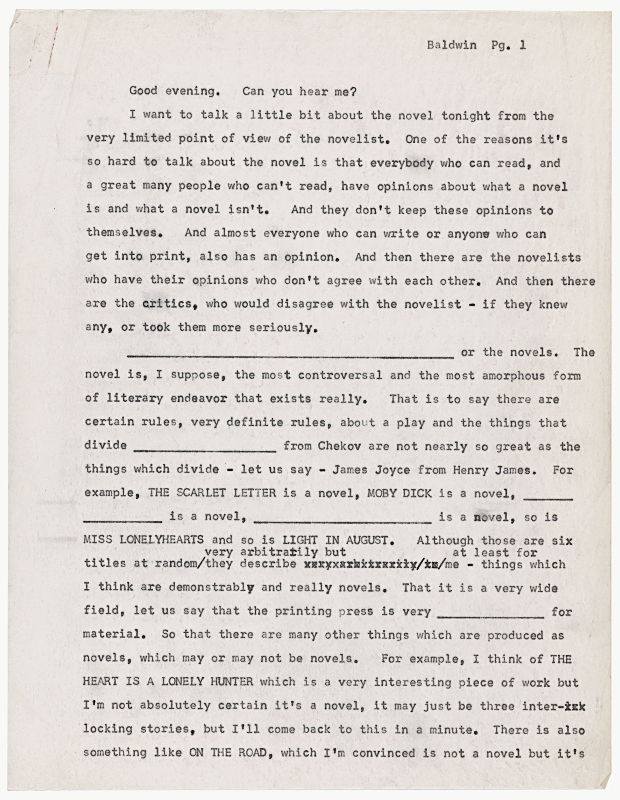

James Baldwin closely edited his speech, “The Novel.”

Pretty much every famous writer, from Stephen King to Annie Proulx, has said some variation of the maxim: “To be a good writer, you have to be a good reader.” Possibly the most entertaining version comes from Ray Bradbury: “If you stuff yourself full of poems, essays, plays, stories, novels, films, comic strips, magazines, music, you automatically explode every morning like Old Faithful.”

Reading, as Bradbury suggests, provides the kindling and lighter fluid that fires up your writing. Reading—especially reading captivating, colorful, creative writing—is also the only way to become a captivating, colorful, creative writer.

Academics tend to read a lot, but they often do so in information-gathering mode, skimming for an argument or data. Reading in a slower, writerly way, on the other hand, can refocus your attention on how stories can connect people and help express a range of human experiences across space and time. James Baldwin put it memorably: “You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read. It was books that taught me that the things that tormented me most were the very things that connected me with all the people who were alive, who had ever been alive.”

It’s also hugely beneficial to read outside of the literary traditions you are accustomed to. Doing so can open new ways of understanding narrative structure, character development, wordsmithing, and worldviews. Of course, that doesn’t mean appropriating the style of a particular tradition. In fact, one of the advantages of reading a variety of storytelling traditions is that you may be less likely to appropriate a single style since your brain will be filled with a mosaic of creative approaches. As Matthew Salesses notes in Craft in the Real World, “Writers must read much more widely and much more deeply, if we are to … write truly for ourselves.”

However, unless you have a photographic memory, you’re going to forget the details of most things you read. This is why it’s so beneficial to have a document or a corner of your bookcase or somewhere else you keep articles and books that inspire you. We recommend collecting inspiring writing on various topics that have differing moods. Here’s why:

After you’ve written your first draft, it’s best to put it aside—ideally until the next day or longer, if you can—so you can come back to it with a fresh mind. During this time, you might feel creatively drained. You might dread looking at your draft. So this is an excellent time to read great writing in a similar vein. If you’re writing something dark, read something dark. If you’re writing something funny, read something funny. If you’re writing something that takes place in a certain country or culture—or you’re writing about artists, environmental restoration, or earthquakes—read engaging, ingenious writing about those topics, places, and people.

Then, when you’re ready to edit, you’ll (hopefully) be so full of colorful words, evocative phrases, and creative inspiration that you’ll burst like Old Faithful all over your shitty first draft. (And hopefully avoid mixed metaphors like that one.)

WORKSHOP YOUR OWN WRITING

One way to more powerfully imagine your audience is to create an “avatar,” which is a stand-in for the ideal reader you’re aspiring to reach. This can be helpful for shaping the stories, tone, language, and content you’ll write. For instance, writing for a high school student with a passion for fashion is vastly different from writing for a retiree who is an avid reader of National Geographic.

Start by identifying your avatar’s demographics: age, identifying gender, their geographic location, and career (or former career). Imagine how they’ll discover your piece (for example, forwarded from a friend or through a Google search) and on what kind of device they’ll be reading and when (on a mobile phone on a bus or at a desk during office hours).

Next, imagine their hobbies and interests (fashion, sports, travel). Go deeper still and consider their struggles (poor schools, to be heard, to be understood) and their desires (to learn, to be challenged, to be affirmed).

Finally, to make the avatar even more real, consider drawing a picture of them—and giving them a name! Print all of this and paste it on a wall next to your computer as you write.

When it’s time to polish your draft, “the most important question in revision is ‘Am I bored here?’” Salesses writes in Craft in the Real World. We agree. It’s a mistake to assume that if you’re bored by your writing, it’s because you’re tired of seeing it, whereas a reader encountering it for the first time would find it interesting, Salesses says. “Don’t believe it. … If it bores you, it is simply boring.”

One of the best ways to determine if your essay has sunk into La Brea Tar Pits of tedium is to read your article aloud, either to yourself or to another person. Salesses even suggests recording yourself reading your piece, then listening to the recording as if you were a friend or your intended audience. If you feel your voice sloooowing doooown or your mind butterflying around, you’re probably bored. Either edit that part to make it exciting, or cut it.

Reading your article aloud can also help you suss out other problems. If your tongue trips over the words, your sentences may be overly long or convoluted. If your voice halts and you find yourself momentarily confused, your sentences might not flow logically. You may need to add a transition, or reorder the paragraphs. If, on the other hand, you start reading with momentum, your voice keeps a fairly steady pace throughout, you remain absorbed in the writing, and you end on a punchy note, you’ve probably told a great story.

With these simple tools in hand, Salesses says, “eventually you can be your own workshop, your own ideal reader.”

KEEP TRACK OF YOUR IDEAS AND TIME

TAKE WRITING WORKSHOPS

Here is a brief selection of writing workshops, but note that there are numerous others offered by, for example, universities, nonprofits, and individual writers.

Field Studio, co-run by anthropologist and poet Nomi Stone, offers online and in-person writing classes on topics including how to integrate personal material into nonfiction.

Roots. Wounds. Words. Inc. hosts an annual writing retreat and writing workshops led by and aimed toward people who are Black, Latinx, Indigenous, Brown, and of Color as well as people who identify as LGBTQIA+, formerly incarcerated, justice-involved, or poverty-born.

Kweli offers a conference, workshops, mentorship, and a reading and conversation series for a community of BIPOC writers and other creatives.

Kundiman holds writing workshops for people of color and a retreat to support Asian American writers.

Middlebury College in Vermont hosts the renowned Bread Loaf Writers’ Conferences, which focus on general writing, environmental writing, and translation.

The Society of Environmental Journalists provides resources, fellowships, mentorship, and an annual educational conference for members, who can be journalists, academics, students, or work in similar positions.

The National Association of Science Writers offers an annual conference, plus numerous resources and online talks for members, who can be current or aspiring science writers.

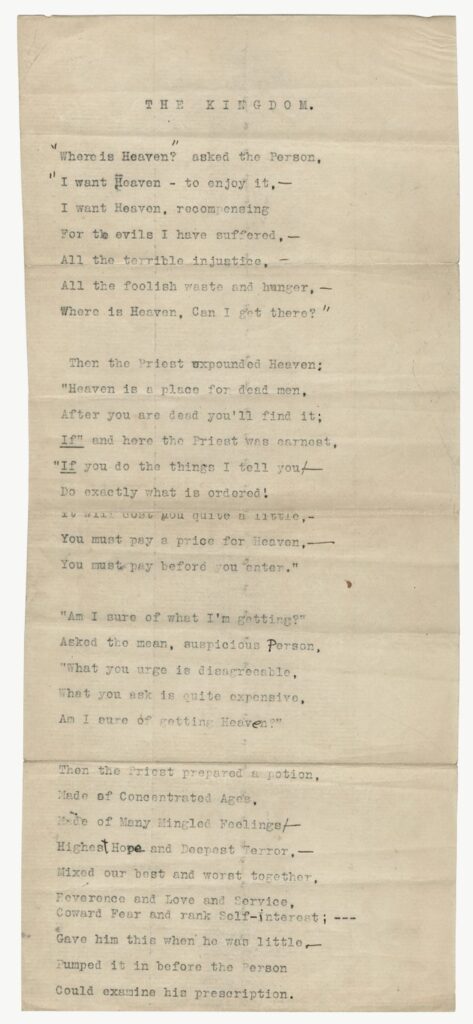

Charlotte Perkins Gilman made numerous handwritten edits to this typed version of her poem, “The Kingdom.”

Manuscript Collection MS-1617/Harry Ransom Center

Sometimes you come up with a story idea, but you don’t have time to research and pitch it immediately, and you think you’ll remember it. You probably won’t.

So it’s smart to keep a spreadsheet, folder, or document where you store pitch ideas along with a link or note about the source of your idea. You can also keep notes like “November 2024 is the 50th anniversary of X important event. Pitch a story in July.” It’s also a good idea to manage your internet browser’s bookmarks so you can save articles for future research under different topics.

In addition, you may be pitching several ideas at the same time or have an idea that you pitch to multiple publications that keeps getting rejected. It’s helpful to keep track of these pitches in a spreadsheet as well, especially if you’ve made a goal to hit a certain number of rejections per year. In this spreadsheet, you might include the idea, the publication and editor you pitched, the date you pitched, the status (“accepted,” “rejected,” or “silent treatment,” for example), and any relevant notes, such as “editor suggested I retool the pitch and send it to the op-ed department.”

Furthermore, keeping track of the time it takes you to write each essay, including conducting research, is extremely useful for helping you determine how much time you need to allocate for similar articles in the future. Spoiler alert: It’s almost always much more time than you expect. Toggl and Clockify are free, user-friendly, online time trackers, but there are other sites and apps as well.

JOIN OR START A WRITERS GROUP

Novelist Thomas Mann quipped, “A writer is someone for whom writing is more difficult than it is for other people.”

The writing life can be hard. It’s sometimes challenging to kindle the motivation to work on public writing when you have so many other responsibilities to juggle. And as we mentioned earlier, it’s often difficult to determine which publications to pitch, which editors to contact, and what their emails are. For these and other reasons, joining or starting a writers’ group can be hugely beneficial.

You may be able to find some established anthropologist writers’ groups, such as AFA Writes, an online group for feminist anthropologists. In addition, the literary nonprofit Kundiman lists numerous organizations that support writers of color. It’s also very common for participants in writing workshops to form a writing group or, say, Slack-based support network after the workshop is over. There are also online groups among journalists and other public writers that are secret, so, unfortunately, we can’t tell you about them. But if you’re at a conference or workshop, and you sidle up to other writers, journalists, and editors and ask them, they may be able to tell you about these underground groups.

In addition, various writing organizations offer databases you can join to find editors, collaborators, experts, and more. The Open Notebook recently launched a Science Writers Database that’s open to writers, journalists, and other public communicators.

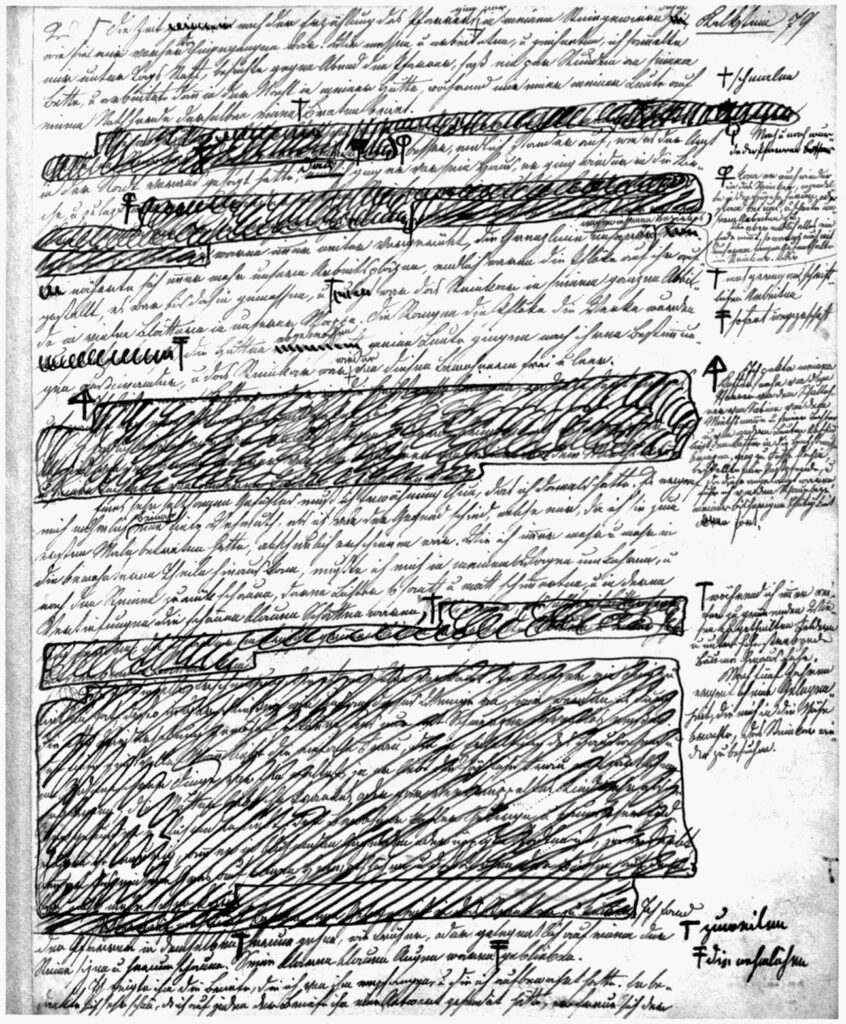

The Bohemian-Austrian writer Adalbert Stifter closely edited his manuscript for his novella, Kalkstein (Limestone), published in 1853.

Bayerische Staatsbibliothek/Wikimedia

PROMOTE YOUR WORK ON SOCIAL MEDIA

Despite upheavals and uncertainties on various platforms, social media remains a valuable tool for spreading the word about your public writing and for networking with colleagues. The popular platforms for promoting public writing are still Facebook, Instagram, and (especially) X (formerly Twitter).

The algorithms favor people who post frequently and whose posts are liked and shared often. So even if you find social media as enjoyable as a root canal, it’s beneficial to stay active. Social media can also be a way to build community and find people who care about the stories you do. For example, anthropologist Irma McClaurin uses social media and other public engagement to share her passionate interest in the work of anthropologist and writer Zora Neale Hurston.

If you don’t like talking about yourself, focus on complimenting your colleagues and linking to articles or papers they’ve published, job openings or fellowship opportunities at your institution, and other similarly supportive actions.

When you do post about your public writing, tag the publication you’ve written for (and your editor if they’re active on the platform) and thank and tag the people you interviewed or who helped you in your research. This will make it more likely that they’ll repost and like your post. It also helps boost their prominence on the site and their standing in their field. While experts now recommend reining in the use of hashtags, one hashtag maximum per post is fine. #AnthroTwitter can be useful, as are hashtags for niche fields or topics, such as #MedicalAnthro.

Also, make sure you follow anthropological organizations on social media and, if appropriate, tag them in a post when you have a relevant article published. In addition, cultivate relationships with your institution’s press office; they’re usually great at publicizing public writing from faculty and staff. For more tips, read our Ask SAPIENS article on how to promote your research on social media.

Activities

Looking Back

-

Reflection activity

Did you do the first activity in Module 1 in which you made a list of your concerns and the barriers you face to writing for the public, and then wrote down why you want to write for the public? If not, you can think back to where you were then and jot down those items now. If you did do the activity, look back at what you wrote.

Next reflect on where you are now. How do you feel about your previous concerns and the barriers you face? Have your reasons for wanting to write for the public changed, or have your goals solidified? If you’re feeling a lot more knowledgeable about how to advance your work as a public anthropologist, celebrate that.

Now write down one thing you can do right away to kick-start your public writing.