Chapter 2

What to Expect, from Pitch to Publication

Writing for the public is a puzzle, discovering how your piece fits the publisher’s and audience’s needs.

INTRODUCTION

The realms of academic publishing and popular media are a bit like neighboring countries: They share many commonalities, but the culture, protocol, pace, and terrain are different.

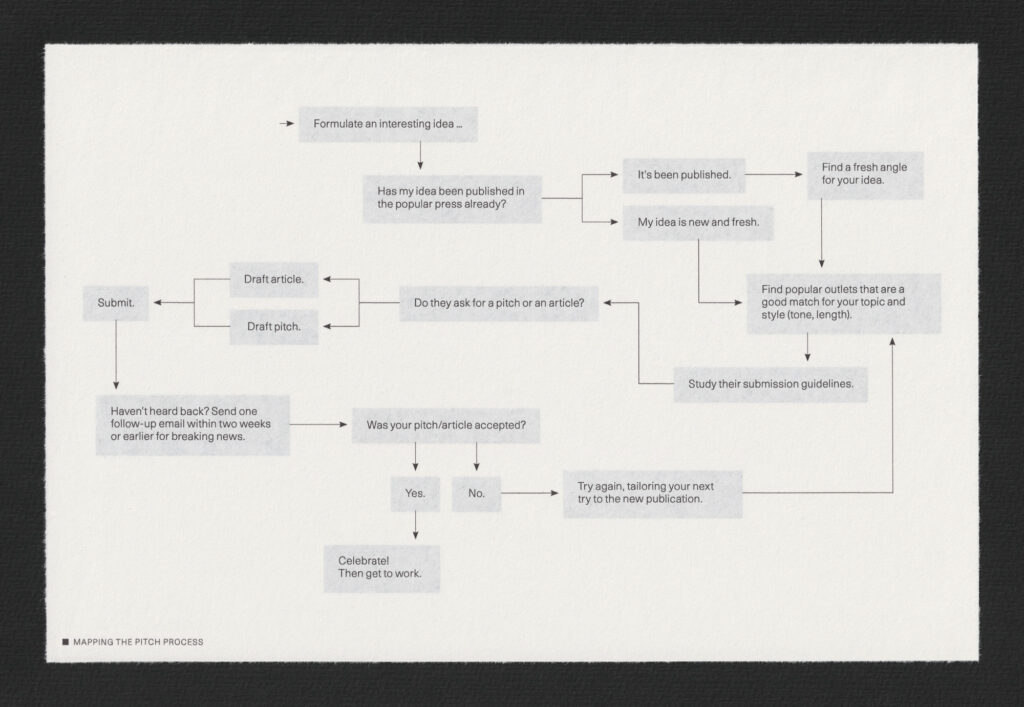

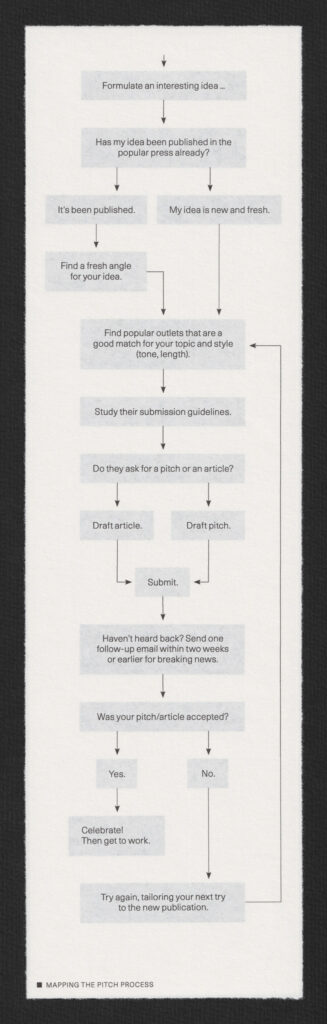

So before we delve into how to write compelling pitches and stories, this chapter will provide a road map to getting published in newspapers, magazines, and online outlets.

We’ll cruise through the process of choosing a publication, pitching your idea, and working with editors. Along the way, we’ll answer common questions about etiquette, time frames, the nitty-gritty of editing, and more.

We’ll also let you in on a few tricks of the trade to help your publishing journey go more smoothly.

FIND THE RIGHT OUTLET FOR YOUR IDEA

David Graeber was skilled at shaping different stories, often with the same theme, for particular outlets.

Guido van Nispen/Wikimedia

When writing for popular media, everything begins with your idea. It might be a powerful tale from your fieldwork, a personal story interwoven with anthropological insights, or a fresh take on a timely phenomenon. In contrast to academic publishing, you typically do not write the article first. Instead, you write a brief summary of your idea and shop it around to publications (more on this “pitch” process below). After an editor accepts your pitch, you’ll discuss the details, and then you’ll write the story according to those specifications.

Because media outlets can differ widely in the style, tone, and length of stories they publish, your idea could morph into very different articles, depending on where you choose to pitch it. So it’s smart to consider the “personality” of your target publication(s) from the beginning.

To illustrate why, let’s talk about bullshit jobs.

In 2013, the late anthropologist David Graeber published a manifesto on what he called “bullshit jobs” in Strike magazine. Because Strike is geared toward anti-oppression activists, the article’s tone was simultaneously strident and philosophical. Years later, Graeber published an excerpt from his new book in The Guardian about the same topic. This essay was more conversational and colored with storytelling, anecdotes, and quotes from interviewees.

Around the same time, Graeber wrote about B.S. jobs in academia for The Chronicle of Higher Education. He peppered this piece with statistics and personal stories about his positions at universities. All these articles were about the same phenomenon. Yet the tone, style, substance, and research required for each story were quite different, and their length varied by 2,400 words.

Because of this potential variation, it’s a good idea to form a vision of what you’d like your article to be and who you would like your story to speak to before you pitch it. Next, find a publication that’s compatible with that vision. Browse potential outlets and consider the subject areas, style, length, and tone of the articles they typically publish. Search for keywords related to your idea to see what, if anything, each outlet has published on that topic in the last few years. If your idea is too similar to a recent story, you’ll need to come up with a new angle or target a different publication (possibly both).

While it’s tempting to aim for the most prestigious publications, those might not be the best choice. For example, if you want to write a lyrical or humorous essay, but the outlet you’re considering delivers breaking news in a straightforward style, the editors probably won’t be interested. And if they do assign you the story because they like the concept, they will likely edit out all your witty, poetic language.

You might even consider creating a website or blog to feature your writing. Although you may not gain a large audience, you will have the freedom to write as you wish.

It’s a bit like dating: No matter how great you are, not everyone is going to be compatible with you. You’ll probably be much happier with the final result if you choose an outlet that’s a good match for your voice and vision in the first place.

SEND A COMPELLING PITCH

Once you’ve found your target publication(s), read their writers guidelines. (These may also be called submission or pitching guidelines, and most publications post them on their website.) Many English-language magazines, newspapers, and online outlets are open to receiving ideas anytime, but some publications take pitches only during certain windows throughout the year.

Some outlets prefer to see a completed op-ed (opinion piece) or a personal or literary essay. But in most cases, outlets ask writers to send a pitch—a short (approximately 300-word) encapsulation of the story idea. The pitch is designed to capture an editor’s attention and tell them why this story matters now and why you’re the person to write it. In Chapter 3, we’ll dive into how to transform your idea into an irresistible pitch. But for now, let’s address some common questions about the pitching process.

If your idea is linked to breaking news, pitch immediately and be prepared to write very quickly. The turnaround time will most likely be less than a week, and it could be as little as a day!

If you’re pitching an idea pegged to a holiday or an anniversary of an event, try to pitch at least two months in advance for online-only articles and newspapers and six months to a year in advance for print magazines. Most publications schedule their production calendars many months or even a year in advance and typically take months to edit stories. Plus, publications typically want only one or two articles pegged to an event, so pitching early means you’re more likely to get ahead of the competition.

If the publication’s guidelines request the entire op-ed rather than a pitch, they usually have a webpage where you can submit your draft for consideration. The Washington Post and The New York Times have such submission pages, for example. If the publication does not have a specific process for submitting op-eds, send a pitch as you would for other types of articles.

It’s complicated.

If the publication’s guidelines ask you to send your pitch through their Submittable page (as SAPIENS and Emergence Magazine do, for example), it’s best to follow their instructions. These are typically smaller publications, where multiple editors may weigh in on a pitch, so they like to keep pitches in a centralized place, and they monitor Submittable regularly.

Alternatively, some publications’ guidelines ask you to send a pitch to a general email address, such as info@publicationname.com, or through a form on their website. At some publications, these general emails or forms are monitored consistently. At others, they are the editorial equivalent of a black hole. Therefore, journalists almost always prefer to pitch an editor’s direct email.

The trouble is, editors rarely post their email addresses on the publication’s website. That’s mainly because they don’t want to be inundated with spam, ads, and abuse from internet trolls. They do, however, want to hear from writers with solid ideas. It is proper etiquette to pitch an editor directly, but you may have to go on a quest to uncover their email.

First, check the publication’s masthead to see if there’s an editor responsible for your topic. If not, look for a news editor, senior editor, or deputy editor. Then search for their name and see if they’ve posted their email address on their X (formerly Twitter) page, in a blog they wrote about pitching, or in their bio for a writing conference they spoke at, for example. You can also just guess: An address like firstname.lastname@publicationname.com is a good place to start, but there are numerous variations on company emails, so it may take several tries.

Some publications—particularly magazines, including Scientific American and Smithsonian—have different editors for the print and online versions. At many newspapers, by contrast, the same editors cover both versions. You can find this information by looking at each publication’s masthead online.

If you would like your article to appear in a print magazine, scan the different sections at the front of the magazine and tailor your pitch to a specific section. Alternatively, if your idea is for a feature—the longer, narrative, and often character-driven articles that typically fill the center of a magazine—you can specify that. You may have a perfectly good idea, but if the editors don’t know where to place it in the magazine, they can’t accept it.

If you’re aiming for the magazine’s website, you’ll have a lot more flexibility. It’s also usually easier to get your start on the website if you haven’t written for the publication before.

The answer to this question is constantly debated. Currently, the consensus is that if you’re pitching an idea relating to breaking news, it’s OK to pitch several publications, as long as you let the editors know you’re doing so. If the story is more evergreen (not urgently newsy or pegged to an imminent event) or you’re pitching well in advance, pitch one publication at a time. Or if an outlet specifically asks for an exclusive pitch, be sure to respect their request.

Unless it’s breaking news, the typical protocol is to wait two weeks after you’ve pitched, and if you don’t hear back, send a polite follow-up email to ask if they’re interested.

Editors don’t mind if you follow up within a reasonable amount of time. In fact, they often welcome it. Editors’ inboxes are usually full, and sometimes emails slip through the cracks. Alternatively, they may be waiting to get feedback from other editors at the next pitch meeting. Don’t assume it’s a “no” if you haven’t heard back in a couple weeks. Always follow up.

If you’re pitching a breaking story, you can follow up more quickly. Some writers put a note in their pitch email saying something like, “Since this is breaking news, if I don’t hear back by X date, I’ll assume you’re passing on this pitch.”

Rejections are so common in popular media that some freelance journalists set a goal of receiving 30, 50, or more rejections per year. This doesn’t mean they’re not putting a lot of effort into each pitch. But they’re also helping themselves overcome a fear of failure and stay positive when they inevitably receive some rejections.

If you get a “no, thanks” or (very often) silence, don’t assume it reflects negatively on your idea or writing ability. Editors sometimes decline quality pitches because they’ve already assigned a similar story. In other cases, one editor might love an idea but get overridden by another editor. In other situations, it’s a matter of personal taste.

If an editor gives you feedback on your pitch, you can take that into consideration if you wish and rewrite your pitch for another publication. But most likely, you won’t receive feedback. Simply pitch a different publication, remain optimistic, and celebrate that you were bold enough to send a pitch.

COLLABORATE WITH AN EDITOR

If your pitch is accepted, congratulations! Take a moment to celebrate, and then get to work.

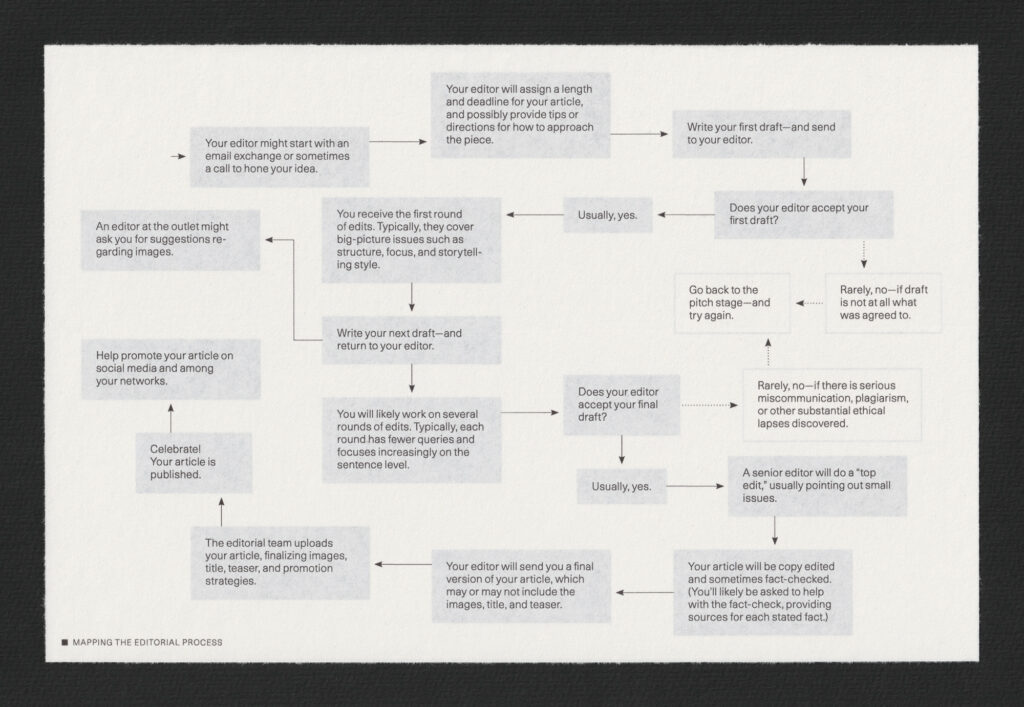

At this point, your editor will likely give you a word count, a deadline, and some basic directions on structure and focus. Sometimes you might discuss various potential approaches and people you might interview and/or reference. You may receive a contract to sign, or you may simply get an email confirmation (which does constitute a binding assignment).

We’ll discuss the writing process in subsequent chapters. For now, let’s answer some common questions about what happens after you turn in your first draft.

If it’s a breaking story, your article could be published in as little as one or two days. More likely, it will take anywhere from three weeks to three months. If the story is evergreen, it may take several more months, depending on your schedule, the editor’s calendar, and the length and topic of the story. Naturally, a 600-word straightforward op-ed or breezy, personal essay will take much less time at every step of the process for you and the editor than a 5,000-word feature about a nuanced, sensitive, and controversial issue.

There will typically be two or three rounds of developmental editing. Your developmental editor will address overarching issues of structure, paragraph order, focus, storytelling, style, and sentence-level changes to make the article clearer and more compelling.

Next, at most publications, a deputy editor or editor-in-chief will perform a “top edit.” This editor looks at the piece with fresh eyes, usually incorporating very minor changes for clarity but sometimes requesting more substantive changes. Finally, a copy editor will perform a copy edit, which can involve everything from grammar and style to sensitivity issues.

Some publications also fact-check each article, while others expect the writer to do so. (We’ll cover fact-checking tips in Chapter 6.) Usually, an editor sends the writer a final version of the article for approval, but that’s not always the case. Do feel free to ask your editor to send you the final version for your review before publication.

This varies greatly by publication, individual editor, and each article. Sometimes your editor may make minor tweaks and add suggestions for how to rephrase sentences. In other cases, they’ll request larger changes, such as starting with a story instead of introductory facts or moving a story from the final paragraph to the first paragraph and finding a new way to end the essay. At other times, they’ll rewrite huge swaths of the article.

When your writing is substantially edited, it can be discouraging. But remember that one of the main reasons editors are necessary is because writers and researchers often know their topic so well that their brains unconsciously fill in blanks with information. Academics may be used to writing for their peers, but engaging a nonspecialist audience requires different storytelling techniques that your editor can help you navigate.

Also, writers are often enthusiastic about their topic for a variety of reasons that may include years of personal experiences. The publication’s readers, on the other hand, may have no knowledge or experience of the topic. The editor’s job is to see the article from the reader’s perspective and supply them with all the necessary information and reasons to be enthusiastic. That may require significant edits. In Chapters 6 and 7, we’ll discuss tools for self-editing to reduce the chances that your editor will need to make substantial changes.

Editing should be a collaborative process. So it is absolutely possible to discuss changes with your editor, ask why they made a certain edit, and suggest alternative phrasing.

First, reflect on each change, why you’re unhappy with it, and why the editor may have made the change. Often it becomes apparent that the original text was unclear, jargony, dry, or wordy and needed improving. Perhaps you can suggest another way to phrase the sentence that solves the original problem but sounds more like your desired voice or style.

In some cases, the edits may not sound like your voice because you normally write academically. The edited language may feel more casual, colorful, dramatic, or playful than you’re used to. If so, ask yourself: Is the casual or playful tone appropriate for the subject matter? Is the style merely dramatic, or has it veered into sensationalism?

If the tone is appropriate and the style is not misleading or overstated, the article may be much better for the changes, even if the writing is different from your normal style. But if the edits are inappropriate, misrepresentative, or incorrect, definitely discuss these issues with your editor. Editors do inadvertently make errors of fact or judgment, and they welcome writers’ input and expertise on the subject.

The writer almost never writes the title and subhead (known as the “hed” and “dek” in journalism). However, you can make suggestions, and you’ll often be given an opportunity to provide feedback before publication.

Often your editor or the art editor will ask if you can provide photos, especially if it’s a personal essay or a feature about your fieldwork. If they don’t ask, feel free to offer to send photos or other images, such as maps or graphs. Ultimately, the editors have the final say in the images chosen, but you can provide input about the photos and captions. And if you have sensitivity concerns, such as not showing images of human remains, let your editor know.

This will depend on your audience and the outlet you publish in. For some audiences, charts, infographics, and other visuals can help clarify points or condense complicated information. However, most large publications won’t expect you to produce these, so be sure to suggest any ideas to your editor as soon as possible. And if you have some stunning photography, audio, or video content, be sure to share these assets with your editor and let them know your vision of how to incorporate them.

Payment ranges widely, from nothing to US$1 or more per word (or the equivalent in other currencies). It varies by publication and often differs within publications, depending on whether the article is online-only or also in print, as well as what kind of article it is (op-ed, Q&A, or feature, for example). SAPIENS offers US$250 to each contributing author, up to three authors, per published piece.

Nearly all assigned articles are published. However, in rare instances, an article may be pulled in the production process (“killed,” as journalists unfortunately call it). This could happen due to unforeseen circumstances—maybe the event you’re writing about is unexpectedly canceled, or the main person you’re featuring suddenly can’t be reached. If something out of your control occurs, you may be entitled to a “kill fee”—partial payment for a canceled article. You can discuss this with your editor, or it might be stipulated in your contract.

Most publications require rights to your article that do not permit it to be republished. However, some outlets offer the option of publishing an article under the Creative Commons license. This allows other outlets to republish your article with your author byline. They may change the headline and subhead but can make only small stylistic changes to the text. Images are not included in the license and require separate permission to republish. You can read about SAPIENS’ rules for publishing under the Creative Commons license here.

Publications usually have a dedicated person or team and a multipronged strategy for sharing content with their audience. Still, writers are always encouraged to promote their work on social media (more on that in Chapter 7). And it’s perfectly legal and customary for writers to link to their work or provide PDFs of their articles on their personal website.

Activities

Research Outlets and Ideas

-

Publication analysis activity

Find two or three publications you’re interested in writing for and look at their recent stories. If it’s a magazine, browse the different sections to see the specific categories, topics, and length of stories they’re looking for. Look over the latest few issues. If it’s an online outlet, skim several recent articles to get a feel for the mix of stories. Ask yourself if each publication fits your voice and ideas.

-

Idea research activity

If you have a story idea in mind, search the internet for recent popular media articles about that topic. If you see stories that are similar to your idea, that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t pitch it, but you’ll want to make sure something about your angle is fresh and different. Note how other writers approached the topic. Do you feel something is missing from their coverage that could be incorporated into your story?