Chapter 6

Navigating Ethics and Reducing Harms

Ethical storytelling entails exploring and empathizing with the perspectives around you.

INTRODUCTION

When writers turn in an article to an editor, they’re sometimes gripped by thoughts of fear and self-doubt: Did I get the facts right? Did I portray everyone with the right mix of compassion, respect, and nuance? Did I say something offensive? Did I make some blunder that’s totally obvious to everyone but me?

This is completely normal. Unfortunately, writers can’t always rely on editors to fix these issues because editors make mistakes too. And often, editors have absorbed many of the same biases and tendencies as writers.

Several recent studies have shown that ChatGPT sometimes spews sexist, racist, false, and all-around offensive writing. This isn’t surprising given the cultural environments the chatbot was trained in. But all humans are “trained” in cultural environments with their own problems, prejudices, and perspectives. Fortunately, humans can choose to reflect on and address their unconscious biases.

In this chapter, we’ll present best practices and resources to help ensure you’ve done everything possible to make your writing sensitive, inclusive, and factual. We assume you’re already fairly knowledgeable about these topics. So we’ll focus on the ways even the best-informed writers sometimes perpetuate harms, misconstrue truths, and miss things that are evident to some people but not to themselves.

We’ll begin by unpacking a paradoxically exclusionary word that, like ChatGPT, holds up a mirror and reveals people’s potential biases.

ASK “WHO IS WE?”

Klaus Vedfelt/Getty Images

In 2019, journalist Sam Kean published an article in Science magazine titled “Historians Expose Early Scientists’ Debt to the Slave Trade.” Rae Wynn-Grant, who speaks frequently about her experiences as a Black female wildlife ecologist, responded with an impassioned critique on X (formerly Twitter), writing, “The language in this piece is irresponsible and it hurts.”

The article quoted a science historian who said, “There’s a tendency to think about the history of science in this … progressive way, that it’s always a force for good. We tend to forget the ways in which that isn’t the case.” Wynn-Grant countered: “Who is ‘we’?” She pointed out that Black and Brown people never forgot these facts, and “we are scientists too.”

The article quoted another historian who commented on the connection between science and slavery, saying, “This is a hard story for us to deal with.” Again, Wynn-Grant retorted, “This ‘us’ refers to Europeans and descendants of Europeans!” thus erasing the perspectives of scientists whose ancestors were enslaved.

Without more backstory, we can’t know whether the author or his sources were intentionally excluding anyone. But the fact that Kean and all but one of the people he quotes in an article about transatlantic slavery present as White should have set off a parade of red flags in the minds of Kean and his editors.

That’s because, as anthropologists know, all humans have subconscious (and conscious) attitudes and assumptions that influence the ways they think and feel about others. These unconscious biases can show up as knee-jerk stereotyping or a lack of awareness that what seems “normal” and “universal” is in fact a specific lens based on their life experiences. Using “we” can reveal the writer’s lens and intended audience (whether conscious or unconscious).

In public writing, using “we” can make readers feel outright excluded or make them distrust your perspective. So when you’re inclined to write “we,” ask yourself: Who specifically am I talking about? Who do I think I’m talking to? Is anyone excluded from that audience?

Of course, there are times when saying “we” is perfectly acceptable. It’s fine, for example, if you’re writing about when “we” as a species started making fire, and “we” means “all of humanity.” It’s fine if you state that “we” means the co-authors of the essay you’re writing.

These training modules use “we” because we think it’s clear it means “we the editors at SAPIENS.” And if you’re writing from your perspective as a member of a certain community, you might need to consider each sentence individually. Sometimes “we” might apply to the entire community, but sometimes your views may differ from others’ opinions.

CONSIDER HIDDEN SOURCES OF EXCLUSIONARY WRITING

RESOURCES ON CONSCIOUS WRITING

The Conscious Style Guide compiles numerous articles, glossaries, and FAQs on writing about race, socioeconomic status, sexuality, health, and much more. These include covering specific groups and identities.

The Open Notebook, which is geared toward science journalists, has corralled language-use resources from numerous organizations, including the National Association of Hispanic Journalists, Gender Spectrum, the National Center on Disability and Journalism, the Dart Center Style Guide for Trauma-Informed Journalism, and many more.

The news organization GBH has created Inclusive Language Guidelines that also combine tips with a plethora of resources, as has the Los Angeles Press Club.

The Global Press Journal offers a glossary-style guide of terms to help writers be more accurate and inclusive.

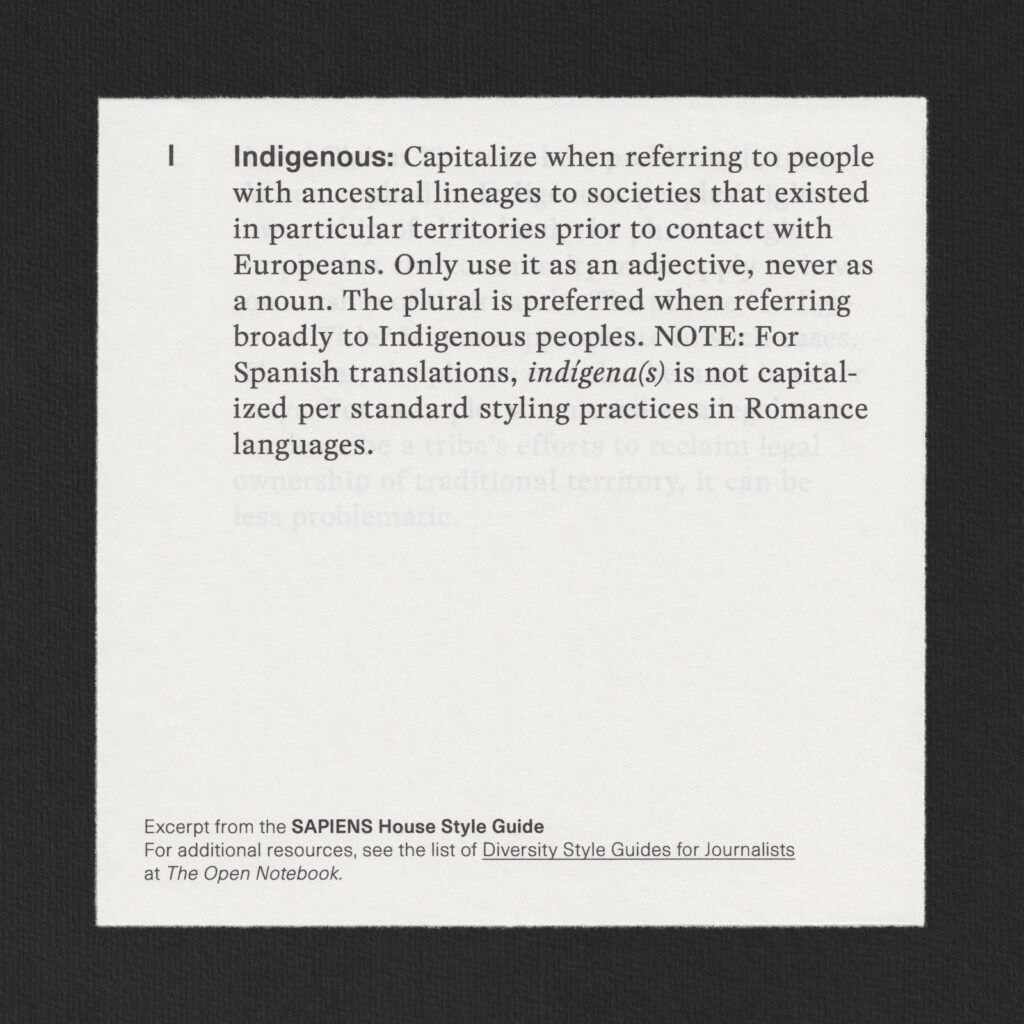

SAPIENS’ Style Guide presents our house style, which includes everything from inclusive and sensitive language to grammar issues.

The book Elements of Indigenous Style, by Gregory Younging, is an excellent guide to writing about Indigenous peoples, with examples of best practices and terms to avoid.

Writing sensitively about issues such as race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, religion, and disability is an enormous and incredibly nuanced topic. We can’t do it justice in this chapter. We also recognize that you may already be up to speed with addressing your own stereotypes, biases, and position in relation to the communities and places you’re writing about.

But remember that many people who will engage with your articles may not be. So it’s critical to take a step back to consider who you are writing for and how those readers’ biases may influence their interpretation of your writing. We hope this section will help you see things from that telescopic view.

In the sidebar below, we’re going to link to numerous resources that can help when you’re writing about a specific community or topic. Before that, though, we’ll zoom out and highlight how unconscious bias can impact writing across various topics.

First, it’s important to note that what you don’t include can perpetuate stereotypes and misrepresentations just as much as what you do include. For example, a writer might state, “In 1920, the 19th Amendment granted U.S. women the right to vote.” If the writer doesn’t provide further context, that statement erases the experiences of many Native American, Asian American, Latina, African American, and other women of color. Many of these women remained disenfranchised long after the 19th Amendment was ratified, either because they were denied citizenship or because state laws deliberately prevented them from voting.

It can be easy to slip into problems of omission because you don’t know what you don’t know or because you might assume readers know as much as you do about a topic. Some ways to avoid this are rigorous fact-checking, constant self-questioning, continuous learning and unlearning, and an openness to engage on these questions with your editor and colleagues.

Another issue that can influence writing across topics is the concept of “defaults.” You’ve no doubt read many articles that take a heteronormative perspective—based on the assumption that cisgender, heterosexual relationships are the default.

As another example, some people object to the term “people of color” because black, brown, and white are all colors, and they say that referring only to Black and Brown people as “people of color” could imply that Whiteness is the default. (Note that this term may be perfectly fine to use as long as the individuals you’re writing about use it to describe themselves.)

It’s important to become aware of default biases in the information you’re consuming, citing, and discussing, so you can avoid perpetuating false or oversimplified norms. While anthropological research tends to encompass a wide variety of demographics, anthropologist writers often reference research from across the behavioral sciences. In these fields, the vast majority of studies are conducted with participants who fall into the category WEIRD: Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic. Therefore, WEIRD people’s thoughts and behaviors are often considered the default, even though such people represent only a small fraction of humanity. In various scientific fields, there’s also a shortage of research involving people who identify as LGBTQ+, disabled, and neurodiverse, which also influences people’s notions of norms and defaults.

In addition, anthropologists who are writing for the public may assume that their audience is WEIRD. This may influence how they present information, including what they assume their audience knows, thinks, and perceives as “normal” or “different.”

How, then, can you present a more inclusive and complete picture of people in your public writing?

Pay attention to who is writing the studies you’re reading and citing. For example, scholars launched the “Cite Black Women” campaign to encourage researchers to read and reference Black women’s work and let such authors’ ideas shape their worldview.

In addition, check the study or studies you’re citing to see how diverse they are—or aren’t. It’s very common to read news articles that say something like, “According to scientific research, humans tend to do X behavior and think in Y way.”

But when you delve into the research, you find that the humans studied were mostly, say, 20-year-old White, heterosexual males attending a university in southern California. If that’s the case, mention the shortcomings of the research in your article or, ideally, try to find papers that include a variety of demographics.

In one instance, the SAPIENS editors worked with an author to develop a story based on research showing that men with low voices are more likely to be perceived as attractive and respectable. We wanted to make sure this was true for a variety of people across the planet. So the article cited studies involving homosexual men, trans men, Hadza hunter-gatherers, and students of varying sexualities and identities at a U.S. university. Doing so made the story more inclusive and strengthened the essay’s premise.

Another potential problem is “writing about” a community rather than “writing with” a community. Articles “about” a community feel like they were written by an outsider from a distance. These articles tend to use generalities rather than specifics. They often reinforce stereotypes, and they usually stick to the surface rather than delve into the nuanced causes of cultural phenomena. As a result, they can portray the community as “Other.”

By contrast, articles written “with” a community tend to include specifics like quotes and real people’s unique experiences. They are rich with context and the nuances of differing viewpoints. The writers of these stories have gained the community’s permission to describe cultural practices and beliefs, and they’ve confirmed the details with their interviewees. These articles present a truer, more respectful, and more empowering picture of communities.

ASK HOW YOUR INTERVIEWEES DESCRIBE THEMSELVES

The resources listed in the sidebar can help you choose the most respectful language when you’re writing about various groups of people. But when you’re speaking about an individual, one source takes precedence over all others: that individual. Use the language people use to describe themselves.

Let’s say you’re writing an essay about autism. You might speak with one individual who calls themself an “autistic person,” another who describes themself as “a person with autism,” and someone else who prefers the phrase “on the spectrum.”

Or maybe you’re interviewing someone who lists their pronouns as “she/they.” This could mean they would like the writer to pick either “she” or “they” and use that pronoun throughout the essay. Or it could mean they prefer that the writer toggles between both pronouns. The only way to find out is to ask.

Another important issue to consider is whether to use identity-first or person-first language. Identity-first language can be problematic if it reduces people to labels like “addict,” “criminal,” or “the poor.” By contrast, person-first language emphasizes an individual’s humanity and complexity. It recognizes that people are far more than their diagnosis, their current income, or the crime they committed years before.

For example, instead of calling someone an “ex-con,” “felon,” or “juvenile delinquent,” it’s more often compassionate and accurate to describe them as a “formerly incarcerated person” or “justice-involved youth.” Instead of referring to someone as a “diabetic,” “quadriplegic,” or “cancer patient,” it’s likely more respectful to say “a person with” diabetes, quadriplegia, or cancer.

However, many people who identify as autistic or deaf prefer identity-first language, such as “autistic person,” “deaf person,” or “Deaf community.” So, again, it’s best to ask your interviewees which phrasing they prefer. And if there’s room for confusion, it’s often a good idea to write a note to your editor explaining how your interviewees want to be described.

SPOT OFTEN-OVERLOOKED ABLEIST WORDS

Studies of news outlets and journalists have identified many forms of bias. You can find an exhaustive list here. A few especially prevalent types of bias to look out for in your writing are:

- Click Baiting: A bias toward stories or reporting that entices readers only through sensationalism.

- Concision Bias: Setting aside the complexity of a story in order to privilege brevity.

- Confirmation Bias: Focusing on what you or your reader already believes while ignoring contradictory evidence or viewpoints.

- Partisan Bias: Reporting stories that serve a particular political party’s agenda.

- Negativity Bias: When negative stories or elements of a story are focused on with the assumption that they’ll grab more attention.

Ableist language—words or phrases that devalue people who have a disability—can seep into essays, even if they’re not about disability. For example, when writing the previous section about unconscious biases, it was tempting to refer to people’s mental “blind spots”; it’s such a common phrase there’s even a book about cognitive bias called Blindspot.

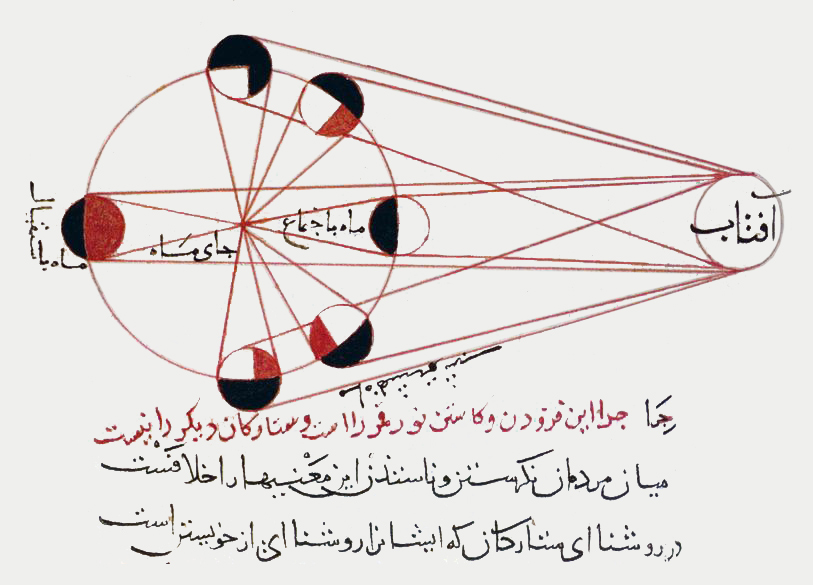

About 1,000 years ago, the famous Iranian polymath Al-Biruni drew this diagram depicting a lunar eclipse, illustrating how parts of our world can be seen and unseen.

Bismika Allahuma/Flickr

But as inclusivity advocates note, metaphors like “turn a blind eye to something” or “blinded by ignorance” perpetuate harmful stigmas against people with disabilities. So do “fall on deaf ears,” “emotionally crippled,” or using the word “bipolar” to describe something as changeable, such as a person’s opinions or the weather. To people with these conditions, reading such words can feel like microaggressions. More broadly, such language perpetuates ableist norms.

Using these words doesn’t mean you’re prejudiced. Offensive terms are the poisoned fruit that grows out of prejudiced cultures.

Take the word “hysterical,” which is both ableist and sexist. It’s originally an ancient Greek word that means “suffering in the womb” (it’s related to the word “hysterectomy”). The ancient Greeks believed that if a woman did something they deemed irrational, like expressing emotions, there must be something wrong with her uterus because it couldn’t possibly be that their society deprived women of virtually all rights. This word still gets lobbed disproportionately and unfairly at women, as it did when then-U.S. Sen. Kamala Harris was called hysterical in 2017 for asking questions during a hearing, which was, in fact, her job.

So it’s important to remember that words are charged with emotion and history, and they have the power to harm or uplift. Speaking of which …

DITCH THESE ARCHAEOLOGICAL TERMS

In “The Lost City That’s Not Lost, Not a City, and Doesn’t Need to Be Discovered,” Chris Begley cautions about the ways in which archaeologists discuss “discovering” things.

Christopher Begley

Anthropological writing is rife with problematic terms that—like ableist, sexist, and racist language—represent the toxic fruit that grew out of colonialism, imperialism, and patriarchy. Let’s take a look at some common terms in archaeology that it’s high time to prune.

These words have most often been used to describe long periods of time for Indigenous communities before contact with Europeans. These terms mean, of course, “prior to recorded, or written-down, history.” But history can mean “the study of past events” or just “past events.” So in the minds of many people, prehistory has an implied meaning: “the time when not much happened before the stuff that was important enough to write down started happening.” This is, of course, patently untrue.

The word “prehistory” erases the rich Oral Traditions of Indigenous cultures, as well as various types of historical accounting, including images, carvings, and systems of writing based on knotted strings, for example. The word “prehistoric” can also be an insult implying “inferior” or “uncultured.” This dismisses the sophisticated technologies, political systems, and creative innovations developed by Indigenous peoples throughout time. These words should be replaced with the specific date range, “ancient,” “pre-contact,” “time immemorial,” or similar terms.

This word may seem neutral, even generic. And that’s the problem. The word “artifacts” usually refers to artworks and functional objects made by Indigenous peoples in the past. Because it’s nonspecific and usually associated with archaeological excavations, the word can imply that these objects are generic and no longer important. It disassociates objects from their forms of expression and meaning.

In reality, these belongings often remain sacred and deeply meaningful to specific communities. So be as specific as possible when describing cultural material’s purpose and significance. And if you’re referring to multiple objects and need a more all-encompassing word, consider “objects,” “artworks,” or “belongings.” Note, however, that “artifact” is generally considered acceptable when referring to objects created by Paleolithic peoples, Neanderthals, and other ancient hominins.

In the context of archaeology, these terms are often linked to settler-colonialist myths that unpopulated places were deliberately deserted by Indigenous peoples, possibly due to “societal collapse.” Settlers often reasoned that they had “discovered” these lands and could claim them for themselves. The word “discover” has, of course, also been used fallaciously to describe Europeans’ arrival in places that had been occupied by Indigenous peoples since time immemorial.

New research and deeper conversations have shown that Indigenous communities often change their societal organization and move for a variety of reasons, including religious motivations and finding better sources of water and food. These communities may return to such places to forage and make spiritual pilgrimages, for example. So the harmful myths behind these words should be scrutinized, and the words themselves should, in most cases, be avoided.

Also, instead of using the word “discover” when referring to an object or practice, consider “find,” “unearth,” or “learn about.”

EXPUNGE THE EXONERATIVE TENSE

In “The International Order Is Failing to Protect Palestinian Cultural Heritage,” Salah Al-Houdalieh speaks directly about the culpability of the Israeli military’s destruction of Palestinian heritage.

Ali Jadallah/Anadolu/Getty Images

Sometimes unclear language isn’t just bad writing, it’s a social justice issue.

Political scientist William Schneider coined the term “past exonerative tense” to describe when passive voice lets people off the hook or diminishes culpability. This sentence structure—and other vague, euphemistic, and circular language—may be rooted in cognitive biases. Or it may be carefully crafted to avoid taking blame, as in the phrase, “mistakes were made.” Either way, exonerative language can reinforce systemic racism, misogyny, victim-blaming, and various forms of prejudice.

Let’s explore how the exonerative tense showed up in news items about the George Floyd case. In plain language, police officer Derek Chauvin killed Floyd by jamming his knee into Floyd’s neck and suffocating him. Yet the initial statement from the Minneapolis Police Department is so whitewashed it bears no resemblance to the murder: “Man Dies After Medical Incident During Police Interaction.”

Several outlets, including CNN, reported that Chauvin “knelt” on Floyd—a euphemistic word that evokes humility and prayer. That’s a totally misleading way to describe a murder. In one tweet, the Associated Press mentioned kneeling but glossed over the killing: “Minnesota authorities say the police officer who knelt on George Floyd’s neck has been arrested.”

One New York Times’ tweet combined passive voice and verbal gymnastics that made it seem like nobody was culpable, except possibly a disembodied knee: “Mayor Jacob Frey of Minneapolis tweeted Tuesday afternoon that 4 officers involved in the arrest of a man who died after being handcuffed and pinned to the ground by an officer’s knee had been fired.”

The exonerative tense distorts people’s perspectives. In one study, researchers looked at news stories about cases of violence against women. They examined the effect of passive voice (i.e., “The woman was abused by the man”) versus active voice (i.e., “The man abused the woman”) on readers’ views. They found that when writers used passive voice, men and women were more accepting of violence against women, and men (but not women) attributed less harm to the victim and less blame to the perpetrator.

Another study investigated the exonerative tense in television news broadcasts about police killings, including the common phrase “officer-involved shooting.” They found that the more obfuscatory the language, the less likely study participants were to believe the police were morally responsible and should be punished.

The exonerative tense has also infected coverage of Israel and Palestine. In numerous instances, articles about Israeli attacks on Palestinians use passive sentence structure to erase the Israeli culprits from the picture. Take the Associated Press headline “Two Palestinians Killed in Separate Episodes in Latest West Bank Violence” and The New York Times headline “Missile at Beachside Gaza Cafe Finds Patrons Poised for World Cup.” One study analyzed more than 33,000 New York Times articles and found that the paper “referred to Palestinians in the passive voice more than twice as often as they did Israelis.”

Because passive voice is so common in academic writing, and the exonerative tense is so widespread in journalism, it’s important to be aware of—and avoid—this linguistic cop-out. But remember that, in many cases, clearly laying blame on someone for a crime before they’ve had a fair trial is also unjust and could constitute libel. So it’s essential to say that a person “allegedly” perpetrated some action or “is accused of” committing some crime, and to cite the organization or individual making the accusation, if that information is available.

RETHINK ANTHROPOCENTRIC LANGUAGE

One thing that separates humans from all other species is that humans are the only ones who constantly write articles about what separates humans from all other species. The notion that humans are separate from and superior to the rest of nature has infected many languages and cultures. This notion is not universal; some societies don’t have words for “nature,” “environment,” or “animal” because these terms inherently imply separation from humans.

Using anthropocentric and dualistic language entrenches harmful and incorrect ideas about humanity’s relationship with the world. There is a growing effort to replace these terms with language that respects the rights of the Earthly community.

Take the term “natural resources,” which portrays plants, animals, soil, water, rocks, et cetera, as things to be used or exploited rather than having intrinsic rights to exist. Likewise, words such as “livestock,” “timber,” and “lumber” imply that these species merely serve human needs (typically by being killed). Words such as “pests,” “vermin,” and “weeds” deem species as deserving of death because they counteract human needs. These can be replaced with either the specific species or more neutral words like “trees,” “wood,” and “insects.”

Human-nature dualism is so entrenched in the English language that coming up with more inclusive words for “nature” is a challenge. You can try “the natural world(s),” “the Earthly community,” and “more-than-human worlds.” But you may get pushback from some editors who aren’t familiar with these phrases and why they matter or who might have concerns about how intelligible they will be to general audiences.

This scan of a typewriter’s type illustrates how even familiar language can always be rethought.

Studio Airport

One of our editors was writing an article for another publication, and her editor rewrote a sentence so it included the phrase “man and nature.” She gave the editor a personal TED Talk, explaining that substituting “man” for “human” is rooted in sexism, and that “man and nature” perpetuates a false duality between humans and nature.

The irony is that her article was actually about counteracting the false duality between humans and nature.

WRITE CONSCIOUSLY ABOUT INDIGENOUS AND WESTERN SCIENCE

Both in the past and today, “Western” scientific communities and English-language media have often not respected the validity of Indigenous science and Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK), which consists of Indigenous communities’ accumulated knowledge of their lands, ecologies, biodiversity, material culture, and more. Thankfully, that’s changing.

Indigenous writers around the world often point out that their communities possess a breadth and depth of knowledge about local ecologies that has sometimes eluded “Western” science. Writers are also spotlighting collaborations between Indigenous and Western researchers that incorporate TEK.

Still, this is a challenging topic to navigate for a few reasons.

One is language. Many people debate what to call “Western” science, since the term is misleading because it has absolutely nothing to do with location in the Western hemisphere. But simply saying “science” erases Indigenous scientific approaches, and using “non-Indigenous science” could imply that Indigenous peoples don’t practice so-called Western science, which is obviously untrue.

Another reason is that “Indigenous” encompasses incredibly nuanced and heterogeneous populations. Writers have sometimes erroneously used the singular terms “Indigenous culture” or “Native American culture,” portraying these cultures as monolithic instead of extremely varied and historically unrelated. Some individuals and communities also prefer not to be called Indigenous, and this term can be problematic in certain contexts. However, it’s sometimes necessary to discuss the similarities that exist across a wide range of Indigenous peoples.

At SAPIENS, we navigated this issue in an article about Indigenous perspectives on psychedelic plant medicines. One of the papers the article referenced, which was written by several Indigenous researchers, encouraged incorporating Indigenous ethics into “Western” scientific research. The authors noted that there are numerous commonalities across cultures in the ways Indigenous societies worldwide view plant medicines and the ethics surrounding them. So we carefully chose phrasing and qualifying words that painted a picture of broad similarities and local differences.

Another hurdle is that, while you may be knowledgeable and experienced in this topic, your editors at media publications may not be. Journalistic editors are often not well-versed in best practices for writing about TEK and Indigenous sciences. And the idea often persists that Western science is neutral, unbiased, and universal, and that anything Western science hasn’t investigated is, by default, unscientific. All of that is untrue. And, again, it’s changing. However, be prepared to have conversations with your editors when it comes to sensitive, accurate word choice and content.

If you’d like to become better informed about this topic, this article in The Open Notebook by journalist Debra Utacia Krol, an enrolled member of the Xolon Salinan Tribe, is a good starting point. It provides examples of exemplary reporting on TEK and lists organizations that can provide referrals for interviewing Indigenous scientists and other experts.

DECIDE WHEN TO USE PSEUDONYMS

The use of pseudonyms can make people feel uneasy. As anthropologist Erica Weiss put it, “We make an active effort to cite other scholars for their ideas, and we also make an active effort to avoid citing our interlocutors for their ideas.” This can smack of paternalism without reciprocity. It can also imply that intellectual property is valuable among academics but not, say, among activists in the streets of Angola. Obviously, this is untrue.

For these and other reasons, pseudonyms should be used sparingly. Still, the world is a dangerous place, and pseudonyms are sometimes necessary to protect interviewees’ safety and to comply with institutional review board requirements. Occasionally, it’s also necessary to withhold the identity of a location. Such masking is often fine as long as you are direct and open about this approach with your reader and why you have taken it.

If you intend to use pseudonyms for your interviewees and/or locations, it’s important to bring that up while discussing the assignment with your editor and before you start writing. Publications have varying policies on the use of pseudonyms, so confirm that you and your editor have the same expectations.

PREVENT PLAGIARISM AND SELF-PLAGIARISM

Frida Kahlo constantly and creatively re-presented herself through self-portraits in new ways.

Frida Kahlo/Wikipedia

Sometimes when you’re writing, an absolutely inspired sentence drops into your head, and you think, “Wow, that’s good stuff. Where did that brilliant idea come from?” And only later do you realize it came from you, and you wrote it in another paper. Or worse: You realize it came from someone else, and you internalized it so much you thought it was your idea.

In rare instances, plagiarism is egregious, and it’s clear the writer highlighted huge swaths of a paper and clicked “copy” and “paste.” More often, though, it’s either unintentional, or the writer is plagiarizing themselves and thinks that’s OK. Self-plagiarism in popular writing is actually not OK.

If you’ve written a lot about a topic or you’re writing about your own research, check what you’ve previously written and make sure you’re not saying the exact same thing. Changing one or two words in a paragraph is still self-plagiarism. And if you’re phrasing something the same way you phrased it in an academic paper, it’s probably not appropriate for public writing anyway. Find a more creative, straightforward way of making your points.

FACT-CHECK EVERYTHING

While writing Training Chapter 1, we nearly fell into a common error. The module discusses the benefits of public writing, so it seemed fitting to reference a Smithsonian article that stated, “According to one 2007 study, … half of academic papers are read only by their authors and journal editors.” Smithsonian is a respected magazine, but publications frequently misquote or misinterpret research, so it’s always necessary to check the original study.

In this case, the link to the study didn’t work. Further digging turned up an article in The Chronicle of Higher Education in which the author, Arthur G. Jago, had searched for the original source of the surprising statistic. Jago traced it to another article that had been cited hundreds of times. But that wasn’t the original source. So he delved further and found that the statistic came from a professor who hastily banged out notes for a communications class he was teaching in 2001 and admitted he probably didn’t fact-check his statements. Yikes!

It’s important to fact-check at every stage, especially since many publications do not employ dedicated fact-checkers.

However, many publications will still ask that you include links to authoritative sources or provide an “annotated draft” with footnotes to references. (See SAPIENS’ guide here.) We recognize that many anthropologists might be wary of fact-checking approaches that consider empirical data from Western scientific research to be the only valid and universal truths. As we mention above, this perspective is changing. At SAPIENS, we consider a wide range of evidence to be valid, including information from ethnographic sources.

Having said that, if it’s possible to confirm something your interviewee said by checking another original source, always do so. Everyone misspeaks or misremembers things sometimes. When you’re fact-checking, be especially cognizant of name spellings, superlatives (when something is the first, largest, or most), facts within quotes, causation versus correlation, and job titles (which often change over time). All of these are common places writers make mistakes.

For more tips, consult these fact-checking guides from the Truth in Journalism Project and the Newmark Journalism School Research Center.

Activities

Rethinking Language

-

Bias-testing activity

Take Harvard University’s implicit bias test to uncover any unconscious biases that may be influencing you.

-

Language research activity

Skim a resource on conscious language. Get a sense of the recommendations included. Choose one recommendation that caught your attention. What is your opinion about this recommendation, and why did it catch your attention? Perhaps it made you feel surprised, affirmed, challenged, confused, or in a state of disagreement.

-

Bias-seeking activity

Find an example of a news article that has bias baked into it. What terms or sentence structures are used to normalize the bias? Or how is it glossed over? Rewrite the most problematic sentences to fix these issues.

-

Artifact-replacing activity

Find an article written for an archaeology journal or popular publication and replace all instances of “artifact” with one of the alternatives suggested above. Consider how that changes the meaning of the article. What else in the article might need change to recognize the ties a particular Indigenous or local community has to a historic object?