Language and Race

Around the world, language functions as much more than a technical means of communication. Conversing with others in a specific language with certain rhythms, styles, registers, forms, and dialects can prompt different modes—sometimes, even categories—of citizenship, connection, and belonging. In this unit, students will learn about language as it relates not only to race relations and constructions of racial identities but also to the maintenance of or challenge to wider discriminatory systems. Through examples from across time and space, students will also gain an understanding of how languages thrive, clash, broaden, or limit people’s access to different groups and spaces.

Black and Indigenous Storytelling as Counter-History

Enfrentando la anti-negrura en la Cuba “ciega a los colores”

La imposibilidad —y la necesidad— de contar las lenguas del mundo

¿Qué es la antropología?

¿Qué es la antropología lingüística?

Cómo amigos sordos y oyentes navegan el mundo conjuntamente

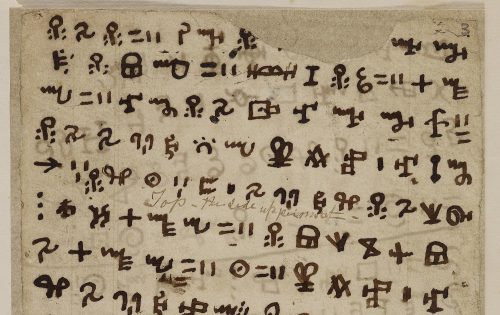

Lo que la grafía vai revela sobre la evolución de la escritura

¿Qué es la revista SAPIENS?

El orden de mi mochila y Tres etapas para nada

La urgencia de imaginar un mundo sin policía

Cómo una confesión forzada dio forma a la historia de una familia

Desenredando la raza del cabello

¿Construyeron las pirámides los extraterrestres?, y otras teorías racistas

Enfrentando la anti-negrura en la Cuba “ciega a los colores”

La imposibilidad —y la necesidad— de contar las lenguas del mundo

Cuando una aplicación de mensajería se convirtió en prueba de terrorismo

Escribir la Tradición Oral indígena para luchar contra una represa

¿Qué es la antropología?

¿Qué es la antropología cultural?

¿Qué es la antropología lingüística?

- Never fixed, language varies not only in terms of the many spoken around the world but also across the different regional, age-related, gendered, and racialized styles that shape and emerge within individual languages.

- Many racialized communities have developed stylistic spins on language for reasons ranging from community-building and identification to convenience to resistance.

- Many mainstream institutions—schools, corporate businesses, formal political organizations—assume, treat, and even demean racialized linguistic variations as inferior, deficient, and inappropriate.

- “Code-switching” specifically refers to when a person incorporates more than one language or dialect in a social exchange. It happens when people assess and adapt their spoken and behavioral practices to fit the expectations of others. Usually this is done in pursuit of specific outcomes including but not limited to leaving a good impression on an audience, getting promoted at work, garnering respect in systems that tend to underestimate one’s racial or other social group, or acting in ways that stand to minimize racial harm that one may face in social spaces that can range from apathetic to hostile.

- Several linguistic anthropologists argue that ethnographic studies of “language” should go beyond the patterns and inflections of verbal expression to include both the contexts (short- and long-term) in which they are used, and the wider array of signals (gestures and movements, attire) and forms (digital media, body language) that people use to communicate and connect with others.

- Language supremacy exists within and between countries and nations, situating some languages and/or dialects as more legitimate, “civilized,” or proper than others. Particularly in political and educational domains, there have been notable recent pushes—through both research and pedagogy—to overturn assumptions that “standard English” is a prerequisite for intellectual prowess, social contribution, and consequently, systemic recognition.

-

Garza, Joyhanna Yoo. 2021. “‘Where All My Bad Girls At?’: Cosmopolitan Femininity Through Racialized Appropriations in K-pop.” Gender and Language 15 (1): 11–41.

-

Hill, Jane H. 1998. “Language, Race, and White Public Space.” American Anthropologist 100 (3): 680–689.

-

Rosa, Jonathan, and Nelson Flores. 2017. “Unsettling Race and Language: Toward a Raciolinguistic Perspective.” Language in Society 46 (5): 621–647.

-

Smalls, Krystal A. 2018. “Fighting Words: Anti-Blackness and Discursive Violence in an American High School.” Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 28 (3): 356–383.

- How does your use of language help shape and affirm your social identities? How do you engage language differently at school, work, or home, or with friends?

- When was the last time you thought about how others might interpret words or unfairly judge you because of them? What pushed you to think about this consciously, and how did that shape your language choices going forward?

- What does language capture or enable in the human experience, and what does it obscure, derail, or otherwise fail to capture?

- How is language used to serve different social and political interests in Obregón’s SAPIENS post?

- Why is it important to pay attention to how people interpret and deploy language, and to how their decisions are informed by their racial realities?

- According to the “Black and Indigenous Storytelling as Counter-History” transcript, what were the cultural powers of storytelling, and how did different speakers see storytelling as resistance?

- Have students define and discuss code-switching in class, and then write—as an individual assignment and follow-up thought exercise—about a time they remember doing so. Ask them to detail not just the incident, time, and people around them, but also their feelings and thought process (both in that moment and retrospectively).

-

Article: Signithia Fordham’s “Dissin’ ‘the Standard’: Ebonics as Guerrilla Warfare at Capital High”

-

Article: Arthur Spears’ “White Supremacy and Anti-Blackness: Theory and Lived Experience”

-

Blog: H. Samy Alim and Imani Perry’s “DEA and Ebonics”

-

Book: Norma Mendoza-Denton’s Homegirls: Language and Cultural Practice Among Latina Youth Gangs

-

Book: Jennifer Roth-Gordon’s Race and the Brazilian Body: Blackness, Whiteness, and Everyday Language in Rio de Janeiro

-

Interview: Alex Shashkevich’s “Stanford Experts Highlight Link Between Language and Race in New Book,” featuring anthropologist H. Samy Alim

-

Podcast: Benjamin Bean, AnthroPod “Raciolinguistic Ideologies and Decolonizing Anthropology: A Conversation With Jonathan Rosa”

-

Video: Stuart Hall’s “Race: The Floating Signifier”

-

Video: Kritika Sharma’s “The Linguistics of Racism: Examining Our Language and Its Power”

Marlaina Martin (2022)

Power and Hierarchies