How and When Did Humans First Move Into the Pacific?

This article was originally published at The Conversation and has been republished under Creative Commons.

In the deep human past, highly skilled seafarers made daring crossings from Asia to the Pacific Islands. It was a migration of global importance that shaped the distribution of our species—Homo sapiens—across the planet.

These mariners became the ancestors of people who live in the region today, from West Papua to Aotearoa New Zealand.

For archaeologists, however, the precise timing, location, and nature of these maritime dispersals have been unclear.

For the first time, our new research provides direct evidence that seafarers traveled along the equator to reach islands off the coast of West Papua more than 50 millennia ago.

Digging at the Gateway to the Pacific

Our archaeological fieldwork on Waigeo Island in the Raja Ampat archipelago of West Papua represents the first major international collaboration of its kind, involving academics from New Zealand, West Papua, Indonesia, and beyond. [1] [1] The authors acknowledge the contribution of Abdul Razak Macap, a social anthropologist at the Regional Cultural Heritage Center in Manokwari.

We focused our excavations at Mololo Cave, a colossal limestone chamber surrounded by tropical rainforest. It stretches 100 meters deep and is home to bat colonies, monitor lizards, and the occasional snake.

In the local Ambel language, Mololo means the place where the currents come together, fittingly named for the choppy waters and large whirlpools in the nearby straits.

Excavation uncovered several layers of human occupation associated with stone artifacts, animal bones, shells, and charcoal—all physical remains discarded by ancient humans living at the cave.

These archaeological findings were rare in the deepest layers, but radiocarbon dating at the University of Oxford and the University of Waikato demonstrated humans were living at Mololo by at least 55,000 years before the present day.

Foraging in the Rainforest

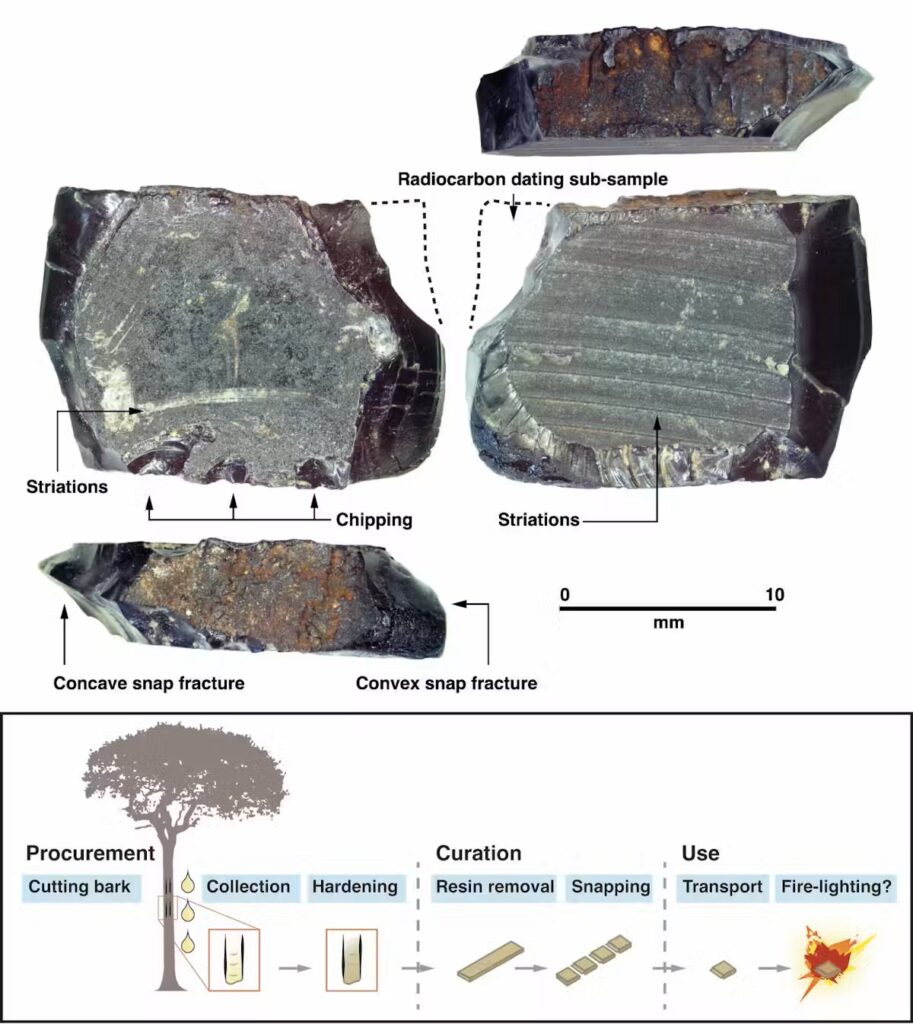

A key finding of the excavation was a tree resin artifact that was made at this time. This is the earliest-known example of resin being used by people outside of Africa. It points to the complex skills humans developed to live in rainforests.

Scanning-electron microscope analysis indicated the artifact was produced in multiple stages. First the bark of a resin-producing tree was cut, and the resin was allowed to drip down the trunk and harden. Then the hardened resin was snapped into shape.

The function of the artifact is unknown, but it may have been used as a fuel source for fires inside the cave. Similar resin was collected during the 20th century around West Papua and used for fires before gas and electric lighting was introduced.

Our study of animal bones from Mololo indicates people hunted ground-dwelling birds, marsupials, and possibly megabats. Despite Waigeo Island being home to small animals that are difficult to capture, people were adapting to using rainforest resources alongside the coastal foods islands readily offer. This is an important example of human adaptation and flexibility in challenging conditions.

Seafaring Pathways to the Pacific

The Mololo excavation helps us clarify the precise time humans moved into the Pacific. This timing is hotly debated because it has major implications for how rapidly our species dispersed out of Africa to Asia and Oceania.

It also has implications for whether people drove Oceanic megafauna like giant kangaroos (Protemnodon) and giant wombats (Diprotodontids) to extinction, and how they interacted with other species of hominins like the “hobbit” (Homo floresiensis) who lived on the islands of Indonesia until about 50,000 years ago.

Archaeologists have proposed two hypothetical seafaring corridors leading into the Pacific: a southern route into Australia and a northern route into West Papua.

In what is today northern Australia, excavations indicate humans may have settled the ancient continent of Sahul, which connected West Papua to Australia, by 65,000 years ago.

However, findings from Timor suggest people were moving along the southern route only 44,000 years ago. Our work supports the idea that the earliest-known seafarers crossed instead along the northern route into West Papua, later moving down into Australia.

West Papua: An Archaeological Enigma

Despite our research, we still know very little about the deep human past in West Papua. Research has been limited primarily because of the political and social crisis in the region.

Importantly, our research shows early West Papuans were sophisticated, highly mobile, and able to devise creative solutions to living on small tropical islands. Ongoing excavations by our project aim to provide further information about how people adapted to climatic and environmental changes in the region.

We know from other archaeological sites in the independent country of Papua New Guinea that once humans arrived in the Pacific region, they kept venturing as far as the New Guinea Highlands, the Bismarck Archipelago, and the Solomon Islands by 30,000 years ago.

It was not until about 3,000 years ago that seafarers pushed out beyond the Solomon Islands to settle the smaller islands of Vanuatu, Fiji, Samoa, and Tonga. Their descendants later voyaged as far as Hawaii, Rapa Nui, and Aotearoa.

Charting the archaeology of West Papua is vital because it helps us understand where the ancestors of the wider Pacific came from and how they adapted to living in this new and unfamiliar sea of islands.