Cultivating Peace in the Heart of the Balkans

On November 28, 2016, Mile Milošević, president of the Serbian War Veterans’ Association, traveled to Sarajevo, where he met with Enver Krluć, president of the Veterans Union of Bosnia-Herzegovina. Their countries had not long ago been mortal enemies. But on this day, they embraced and shared the same message: It was time to heal.

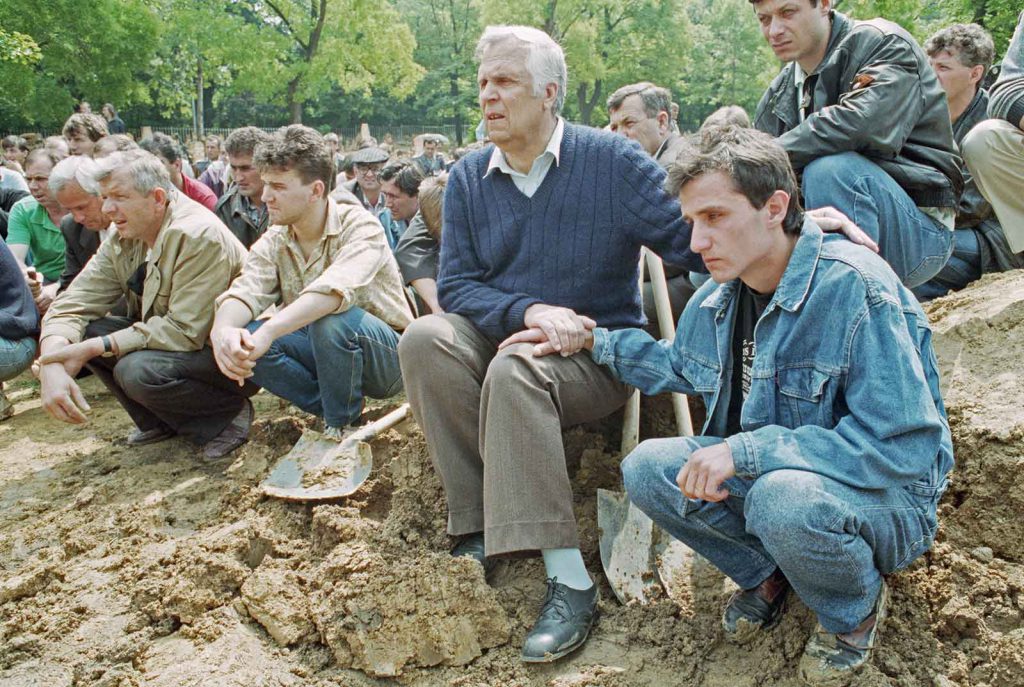

The Yugoslav wars of the 1990s—the deadliest conflicts in Europe since WWII—left over a million veterans in their wake. Many veterans, especially in Serbia, have gone unrecognized and without adequate governmental assistance. They face public stigma and even suspicions that they may have been involved with war crimes. This has made several veterans understandably reluctant to make their own status public, let alone to reach out to those in neighboring countries. But now, at the average age of 53 years old, those who fought on both sides are seeking to reconcile with one another and the wider public, working to promote peaceful relations and denounce the troubling rise of ethnic nationalism in their respective communities.

Reconciliation is not uncommon in the Balkans. Neighbors, friends, and relatives who were once divided by the wars have reunited in recent years. What makes this veteran reconciliation remarkable is that it is happening between former combatants, on a large scale, and without any aid from outside institutions.

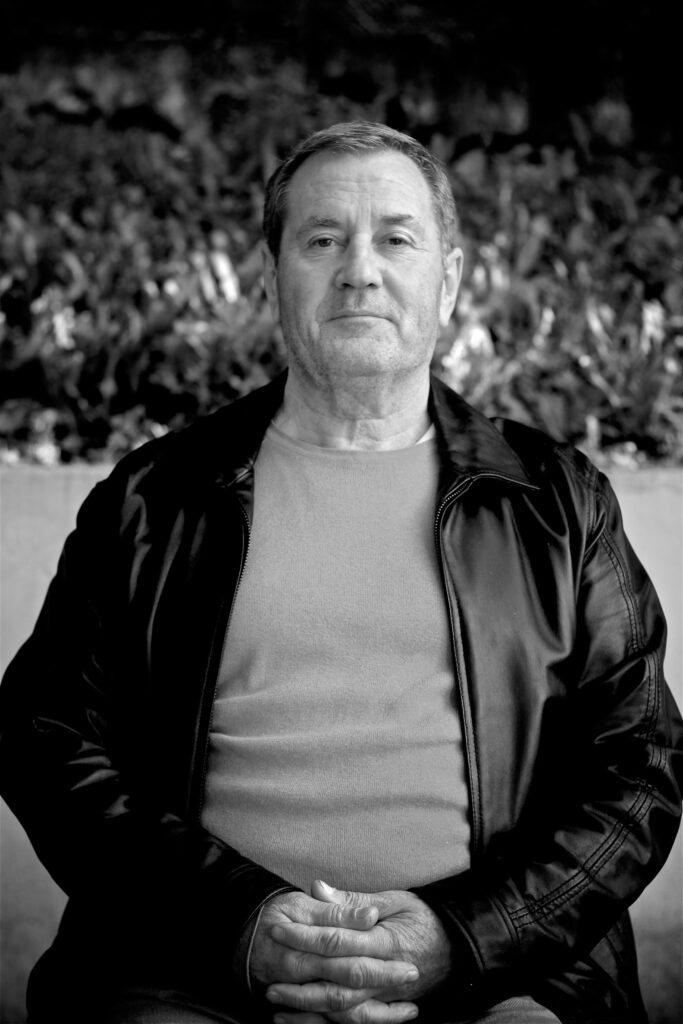

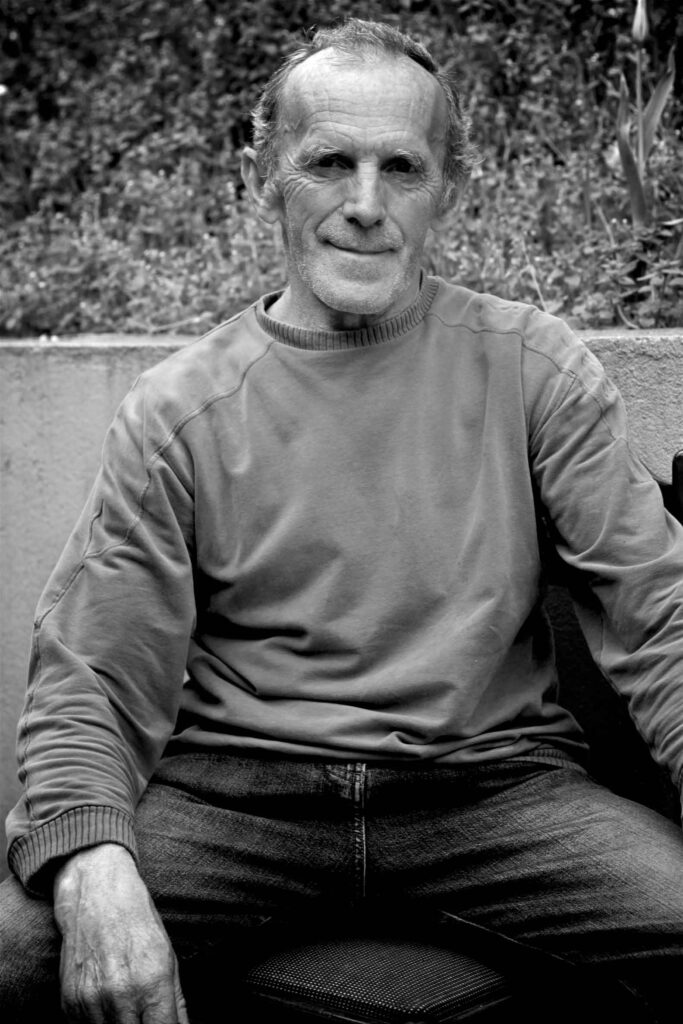

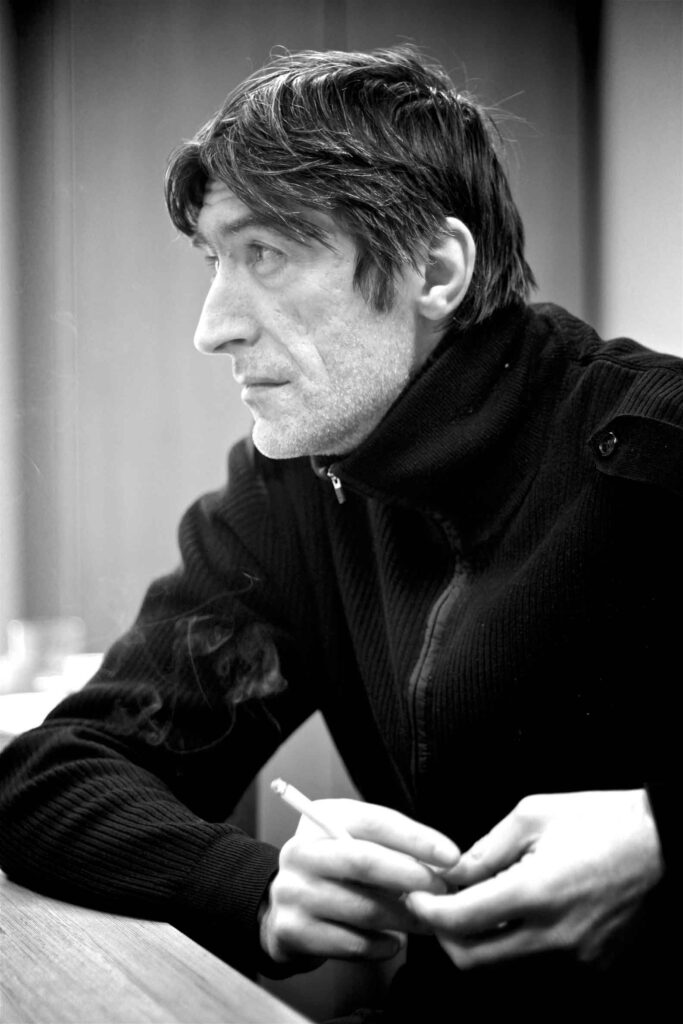

From 2012 to 2016, I undertook ethnographic field research in former conflict regions of Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, and Serbia, where I had the privilege of meeting survivors and veterans of the Yugoslav wars—including women who might not count as official “veterans” but who fought, just the same, to defend their homes. My colleague, photographer Robin Albarano, took portraits of survivors and veterans. [1] [1] Robin Albarano is a photographer and artist living in Los Angeles, California.

The accompanying portraits are of veterans from Milošević and Krluć’s associations who Albarano photographed during individual ethnographic interviews, prior to formal reconciliation. Most of them did not want their photograph taken during reconciliation. Nevertheless, nearly every veteran wanted to share a message about their experience, why they now stood against war, or why they were dedicated to reconciliation. We exclude their names and national identities because most of those Albarano photographed requested that we share the heart of their message and simply portray them as veterans.

We were fortunate enough to be in the region at just the right time to document the inevitable movement toward reconciliation as it took off. The United Nation’s International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) made its final indictments at the end of 2004. In the years following that, discussions about and between veterans slowly began to become more open. People became more willing to talk. Our presence interviewing members of different veterans’ groups also helped to build some bridges; many were curious to hear about our experiences elsewhere, and we were able to connect four of the largest groups in the Balkans—including the Serbian War Veterans’ Association and the Veterans Union of Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Before the onset of war in 1991, the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia included Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Vojvodina, Kosovo, Montenegro, and Macedonia. The people of these republics and territories lived in relative peace and prosperity under the benevolent dictator Josip Broz Tito, a Partisan war hero, who unified the people as “Yugoslavs” under socialism during the Cold War. When Tito died in 1980, he left a power vacuum that was filled with political dysfunction and growing economic crises. With the fall of communism in Eastern Europe in 1989 and the Yugoslavian state’s economic collapse a year later, the door was left open for ethnic nationalists, who were elected in Croatia and Serbia in 1990.

From 1991 to 2001, these nationalists implemented a succession of ethnically based declarations of independence, expulsions, and insurgencies. Approximately 140,000 people were killed, an estimated 50,000 women were victims of rape, and over 4 million people became displaced. From 1993 to 2017, more than a hundred perpetrators of crimes against humanity, including notorious warlords such as Radovan Karadžić and Ratko Mladić, were indicted by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia in The Hague, Netherlands. Nevertheless, many of the leaders and “triggermen” who participated in mass crimes have gone unpunished, or even remain in positions of power, leaving raw wounds in the community.

Veterans of these wars have faced widespread censure, not unlike the popular blame cast on Vietnam veterans in the United States for atrocities by U.S. forces during the 1960s and 1970s. Remarkably, political leaders often portray veterans from neighboring states as perpetrators in order to distance themselves from wartime responsibilities. They also imply that the people who fought in the wars were the true perpetrators, rather than the politicians who ordered the fighting. Several veterans told me that to avoid discrimination, they do not disclose to many others that they are veterans. Such attitudes have prompted all major veterans’ associations in the Balkans to obtain official recognition from the World Veterans Federation—a process that requires them to prove their members are unconnected from war crimes, cooperate with tribunals, and commit to the freedoms declared in the International Bill of Rights. Milošević’s association was one of the most recent to begin the formal process of official acceptance, having had its members cleared and taking the steps toward full membership in the summer of 2016.

Throughout the Balkans, veterans are more likely than any other demographic to live in poverty, carry substantial debt, and receive little or no professional medical services for post-traumatic stress disorder. The situation is most dire in Serbia, where the state offers minimal, if any, assistance to most veterans. These conditions have contributed to a disproportionately high rate of suicide among veterans. In response to these circumstances, numerous veterans have joined protests for greater state benefits. On many occasions, government officials have responded aggressively to these protests by arresting organizers and portraying veteran protestors as rag-tag paramilitaries or weekend warriors who are trying to exploit the state for undeserved benefits.

These challenges have turned many veterans’ associations into social welfare offices, which offer food and shelter to veterans in need. Veterans come together to help raise money for medical needs or to find employment. More than this, they bind together to heal their “moral wounds.” The term, coined by therapists working with U.S. veterans, describes the injury done to one’s conscience or moral compass in war. Reconciliation is an important part of healing veterans’ moral wounds and of spreading a message about the value of peace to younger generations, who are succumbing to ethnonationalistic rhetoric. Of those we spoke with, many said they felt that leaving such a legacy would help them heal from the spiritual injuries left by conflict.

Throughout these nations, veterans’ associations are now reaching out to each other: former enemies brought together by common wounds. It isn’t always easy. For Milošević, traveling to Sarajevo was a risk in itself, since police often detain known veterans whenever they cross the border into a neighboring country to check that they are not wanted for crimes against humanity. Had the police detained him, the Bosnian media would have likely reported that he was detained on suspicion of war crimes.

Throughout his tour of the city, Milošević expressed sorrow and regret for Sarajevans, who were terrorized by Serbian forces when they surrounded the city for 1,425 days. Their siege of Sarajevo resulted in over 11,000 deaths and 50,000 wounded during the Yugoslav wars. Milošević’s openness and empathy was an honest signal to Bosnian veterans that he, and the Serbian veterans he represented, regretted the wars and truly wanted to reconcile. Milošević and Krluć met over a private dinner that lasted several hours. They strategized about how to facilitate reconciliation and spread a message of peace. Afterward, they spoke with the press.

Having interviewed hundreds of veterans and engaged in participant observation (a research technique of observing the lives of a participant population), I learned that veterans of the Yugoslav wars have a picture in their minds of what reconciliation should look like. They strive to connect with one another as former soldiers and bond over shared experiences. They may then lament what was lost in the war. If each party acknowledges and expresses sorrow for the other’s losses, reconciliation is possible; most former fighters simply want their narrative to be recognized by their former enemy. Bonding is often deepened by a mutual denunciation of war; the veterans share expressions of a commitment to peace and discuss their pathways to health and well-being.

However, the lofty goals shared by many Balkan veterans, including Milošević and Krluć, are far from being achieved. Many veterans remain confused about the origin of the fighting and, because of a constant stream of propaganda during and after the wars, about which events really happened. One-third of the veterans I interviewed were not sure what caused the wars and expressed an exasperation about ever being able to reliably know the truth of historical events.

Such confusion renders some veterans reluctant to reconcile, despite the efforts of their associations. Many are also unsure about the best way to come together on a large scale. Distrustful of local nongovernmental organizations, Milošević and Krluć’s associations, in conjunction with others in Bosnia-Herzegovina, have reached out for support from Vietnam veterans, with whom the veterans of the Yugoslav wars feel a kinship. Some Vietnam veterans have gotten involved in the project, with the mutual goal of healing and veteran-to-veteran reconciliation, though it is unclear if they and the Balkan veterans will find the funding needed to make large-scale healing and reconciliation happen.

While these Yugoslav war veterans are attempting to mend the wounds of combat two decades after the wars ended, they are striving for large-scale peace and amity between their nations at the very moment the ICTY is ending its work. That stands as an interesting comparison to other broader societal propitiations elsewhere, such as in South Africa, where the Truth and Reconciliation Commission started in 1995, soon after the end of apartheid. Restoring peaceful relations may be a necessarily slow process. The wheels of justice, like the ICTY, may need to turn before the doors of broader reconciliatory work can be opened. The lesson of the Yugoslav war veterans may be that reconciliation takes place years after the justice system has run its course, at which point former combatants can begin to sense a need to heal from their moral wounds.