Waterloo-Redfern and the Racism Rooted in Cities

This June, a statue of Jefferson Davis, the president of the Confederate States of America during the Civil War, was pulled down by protesters in Richmond, Virginia. It was one of dozens of Confederate statues removed across the country after the killing of African American George Floyd at the hands of police in May. In Britain, during the same week, a statue of Edward Colston, a 17th-century slave trader, was plunged into Bristol Harbor. In Sydney, where I have undertaken ethnographic fieldwork since 2019, a troop of police surrounded a statue of Captain James Cook in Hyde Park to protect the most recognizable symbol of British colonialism in Australia.

The toppling of statues worldwide has reopened an urgent debate about history, memories, and White supremacist narratives. Remarkably, it has put the design of contemporary cities—how we produce, signify, and organize space—back into the center of anti-racism struggles.

Only half an hour’s walk from Cook’s statue in Hyde Park stands another edifice named after touchstones of British colonial times: the public housing estate of Waterloo. It was built in the 1970s as part of the Endeavour project, named after Captain Cook’s ship, HMS Endeavour, and its tower blocks are named after Cook too: Marton building references his birth town, Solander and Banks were two botanists on his ships, Matavai was a harbor Cook visited, and so on. In the central lawn of the estate, a big iron monument stands to commemorate Queen Elizabeth’s visit in 1977.

This public housing estate, the largest in New South Wales, is located on the boundary between Sydney’s suburbs of Waterloo and neighboring Redfern, where I live and conduct fieldwork. Historically, local media has portrayed Waterloo-Redfern as an impoverished area, with a relatively high concentration of public housing, where the local Aboriginal community has been commonly associated with criminality and violence.

In the last decades, an increasing interest of predominantly non-Aboriginal homebuyers in the inner city has accelerated a significant change in this region. Refurbishment of Victorian houses and warehouses, and the redevelopment of former industrial sites have triggered a steady increase in property values, slowly changing the impoverished area into a mostly middle-class neighborhood. As a result, from an estimated number of 35,000 Aboriginal Australians living in the inner-city neighborhoods of Waterloo and Redfern during the 1960s, today the number is fewer than 1,000 Aboriginal people. Low-income residents have been slowly pushed out from their long-term residences.

Recently, a new redevelopment for Waterloo estate has been announced. But rather than reverse the gentrification trend, it risks worsening the historical process of displacement and a presumption of unequal rights to the city.

Against the backdrop of the “statue war,” Waterloo-Redfern stands as a reminder that cities are political spaces. Its story shows how gentrification processes, urban renewals, and public housing policies can reproduce, in complex ways, colonial ways of governing land.

On February 14 of last year, I woke up to an unfamiliar noise on my street in the Waterloo-Redfern area. When I looked outside, I saw two police officers riding horses. Minutes later, the noise was followed by the sound of police sirens—many more than usual. Then a “Public Order & Riot Squad” car sped by.

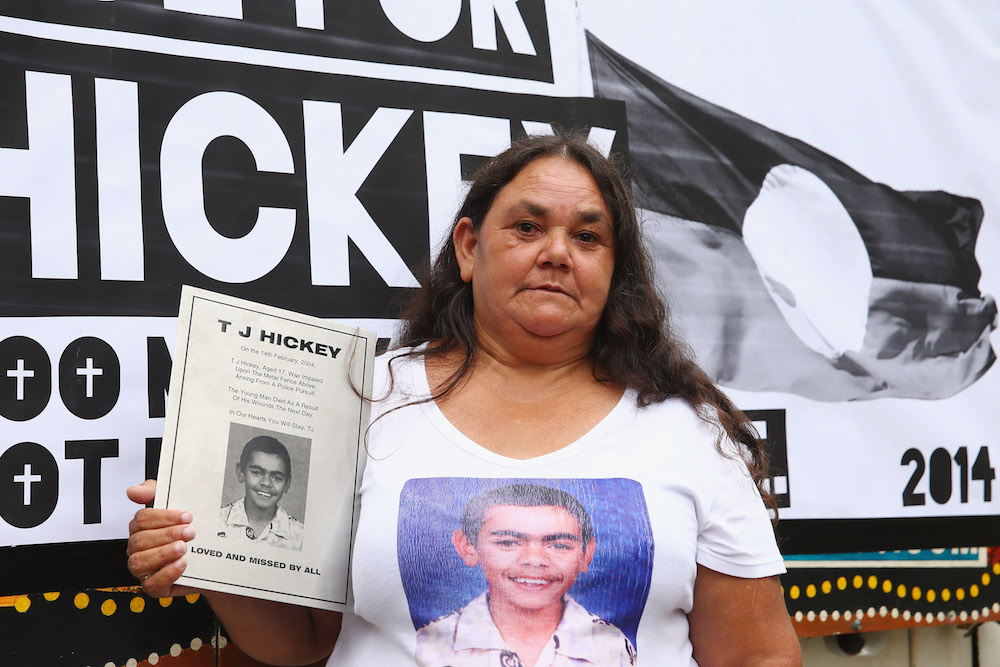

I was intrigued by those scenes, but it was not until I met with other Waterloo residents that I realized what was going on: “Today is the 15th anniversary of TJ’s death,” my friend said. Instead of marking the anniversary with a tribute, the New South Wales police saw it as a potential threat to public order.

In 2004, Thomas “TJ” Hickey, an Aboriginal young man, was severely injured during a police pursuit in Waterloo. The exact cause of his death a day later remains controversial. Police alleged that the teen fell from his bike in an accident. Some local residents accused the police of having hit his bike, which they say caused TJ to be thrown into the air and impaled on a fence.

Following TJ’s death, a massive riot erupted. Residents saw his death as another case of police violence against Aboriginal people and decided to protest, surrounding the local police station and demanding justice. By the end of the night, police used high-powered water hoses to disperse a crowd that was throwing projectiles, with injuries on all sides. Newspaper photos of that night’s events, called the “Redfern riots,” show thousands of people on the streets; many media headlines reinforced the idea of the Waterloo-Redfern area as a dangerous and violent space.

The Waterloo-Redfern area, built on the lands of the Gadigal nation, an Indigenous group, has always held a symbolic importance for the Aboriginal political movement. It was the focus of intense activism and the cradle for various Indigenous organizations that emerged during the 1960s and ’70s: the Aboriginal Legal and Medical Services, The Block, and the National Black Theatre, among others. The place became simultaneously known as a stage for “Blacks politics” and as a space of intense social conflict, criminality, and violence.

The protest triggered an old desire among politicians calling for state intervention. For instance, the leader of the opposition in the New South Wales (NSW) Parliament at that time, John Brogden, said, bulldozers should flatten the area known as The Block to stop “Aboriginal thugs.” And so, the bulldozers came. Shortly after TJ’s death, the NSW government announced the creation of the Redfern-Waterloo Authority (RWA) to revitalize and “improve” the area.

The authority’s purpose was to create new planning rules, identify opportunities for public investments, and pursue public-private partnerships. The RWA was responsible for millions of dollars worth of investments, including the Australian Technology Park, the Channel 7 TV office complex, the new Redfern Police Station, and new residential apartments. After seven years of active work, the RWA was dissolved, leaving a legacy of increased land value, accelerated gentrification, and displacement of low-income renters—including a high number of Aboriginal people—who could not afford to live in the area anymore. The “improvement” was a way of bringing middle-class White people into the area, its policies driven by a racialized fear of Aboriginal people.

On December 16, 2015, residents of the Waterloo estate received a government letter announcing a new redevelopment. At Christmas time, without any previous consultation, the New South Wales government informed residents that their neighborhood would be demolished and rebuilt. According to the proposal, the new estate would follow a “social mix” model, expecting to deliver a 70-to-30 ratio of private to social housing and increase the current 2,000 occupants to around 6,800 residents in the next 15 to 20 years. No timeframe was given in that letter for the project: As of 2020, work has begun on a new public transport station, but planned demolitions have been delayed and have not yet started.

Supporters of the “social mix” model argue that concentrating poverty intensifies its impacts and that higher-income residents act as positive role models for the poor. Such prejudiced assumptions are often used to justify urban interventions that seek “improvement” and “development.” In the case of Waterloo-Redfern, these ideas resonate with early colonial classification of Aboriginal people as morally inferior and unproductive citizens when compared to White settlers.

In February last year, I joined a tenants meeting about the redevelopment. When participants were discussing residents’ issues in the area, one man suggested that local Aboriginal people were the region’s main problem. “They are too basic,” he said. “Aboriginals are welcomed, but they must be polite.”

His idea was not unusual, and it illustrated a broader social perception in which Aboriginal people embody the social malaises of the area. They are seen as the ones who must be “polite,” as if they are inherently impolite. His point revealed troubling notions about who has the right to welcome—or not—other residents into the neighborhood and who has the right to live in the estate.

There is a long history to the racialized sense of ownership and rights in Australia, embedded in things like housing policies. Public housing schemes in Australia have historically favored housing ownership through cheaper mortgages, as opposed to rental occupancy. According to the political scientist Elaine Thompson, this commitment to private home ownership was a central national value, a foundational, nation-building ideology that was part of the “Australian Dream.” While that may sound egalitarian, many housing policies focused on ownership have exacerbated inequality between owners and renters who couldn’t access the government’s cheap loans.

The housing system prioritized low-to-moderate wage workers and often left out those who didn’t fit a particular citizen model: single parents, non–English-speaking immigrants, widows, the unemployed, older people, and, of course, Aboriginal residents. For instance, after World War I the Australian government designed a land allocation scheme for returning servicemen. But while more than 1,000 Aboriginal people fought in the war, governments of the period granted land to only one Aboriginal serviceman in New South Wales.

In Australia, public housing policies and urban transformations hold a fundamental contradiction. They embody both a strong desire for an egalitarian society—an aspiration for a “social mix” and an integrated community—and systemic racism against Aboriginal people and deep prejudice against “others” who don’t fit the nation-building mold.

Waterloo-Redfern faces great social challenges. The current redevelopment proposal for Waterloo does not tackle public housing investment deficit, focuses exclusively on new buildings to be built, and offers no clear commitments to social services such as mental health support or long-term housing maintenance. Local organizations call for at least 5 percent Aboriginal affordable housing in every new redevelopment and development in the state on government-controlled lands. Yet the Waterloo estate project offers no explicit action to resist political and historical conflicts such as Aboriginal land dispossession and structural racism.

Australia was formed through a violent dispossession process supported by the notion of the continent as terra nullius, an empty land. The first towns were settlements that were used to expand the British colony. The British urban model that took hold was—and still is—profoundly connected to imperial logics aimed at controlling land. The foundation of Australian cities is inseparable from colonial history, and the Waterloo estate is part of this complex process by which colonial values seep into Australian housing policies.

As suggested by the Australian urban studies scholar Jane M. Jacobs, colonialism not only happens in space but mainly through space. In other words, the places where we live are not empty, abstract containers where social relations occur; rather, these places are created by those social and power relations.

Racism, in this sense, cannot be seen as solely being about deviant conducts—the behaviors of individual “bad apples” in these cities. On the contrary, what the “statue wars” and the story of Waterloo-Redfern teach us is that racism is also a rationality, as was colonialism, that organizes our public spaces, our urban planning, and, consequently, the ways in which we belong and dwell in place.

Anti-racism struggles require ongoing efforts to disentangle racism’s complex mechanisms. Protestors who have recently toppled statues have thrown a spotlight on the colonial and racist ideologies held by the “great White men” glorified and celebrated in many cities around the world. Similarly, the story of the redevelopment of Waterloo-Redfern sheds light on wider urban politics that sustain the existence of such statues. It illustrates how redevelopments, gentrification processes, and housing policies are also critical pieces of decolonization. It forces us all to think about how we design our cities—and for whom.

Correction: September 17, 2020

An earlier version of this article erroneously used the term Aboriginals as a noun when Aboriginal should only be used as an adjective. The text has been updated accordingly.