When “Voluntary” Return Is Not a Real Option for Asylum-Seekers

Helena and Jonas, a young Austrian couple, first met Musa, then a 15-year-old Pakistani asylum-seeker, at a train station in 2016. [1] [1] Pseudonyms have been used for the author’s interlocutors to protect their privacy. Musa, who had just arrived in Austria a few months before, was struggling to navigate the Viennese public transport system.

Helena and Jonas had never talked to an asylum-seeker and were pleasantly surprised by the teenager’s curious and friendly manner when they offered their assistance. They ended up exchanging numbers that day, then started meeting up to help Musa adjust to life in Austria. Helena and Jonas soon realized that the refugee camp (called a Flüchtlingslager in German) where Musa was staying was adversely affecting him and offered him a room in their apartment as soon as he was allowed to leave the camp.

By the time the couple contacted me by email at the beginning of this year, Musa had become a member of the family. They got in touch with me because they were distraught that Musa had been denied asylum the day before, after several rounds of court appeals. With the final verdicts in from the court, Musa seemed to have only two choices: to leave or be deported to Pakistan.

“We are stunned,” Helena and Jonas wrote. They couldn’t believe that Musa, who had tried so hard to become a member of Austrian society, had been denied asylum. “Musa is an incredibly level-headed, honest, and sincere young man who is patient and open to everything (religion, politics, gender issues, et cetera). It is unbelievable how he [has] dealt with [this] psychologically stressful situation for years.”

Since I’m a South Asian anthropologist who works on “voluntary” returns and deportations from neighboring Germany to Pakistan, they asked if I could provide any information that could help them. With the far right’s influence in Austria, stoking racism and hatred of foreigners, migrants such as Musa often face an uphill battle to get documented.

The situation facing asylum-seekers and immigrants is comparable, if not worse, in other parts of Europe due to growing xenophobia and Islamophobia. Germany, for example, is putting many Pakistanis and Afghans in the same situation as Musa. According to anthropologist Martin Sökefeld, under pressure from right-wing political parties, the country is deporting integrated Afghans if they do not leave “voluntarily.”

Later, over Zoom, Helena and Jonas told me that early on as volunteers working with refugees and asylum-seekers, they were given the impression that all they needed to do was focus on integration. In much of Europe, the rhetoric of “integration” centers on migrants from Muslim-majority countries, who are often perceived as holding “incompatible” cultural values. If Musa became a “good Austrian,” they thought, then why would someone deny him the right to stay in the country?

They explained to me that over the past several years, the three of them had taken that assumption to heart. Musa had worked hard to pick up German within a year and finish secondary school within two years without any prior education. He then progressed to a vocational/polytechnic school. He was on track to complete a two-year training to be a nursing assistant (a position called Pflegeassistent in German) this July. Then he hoped to find employment as a care worker—a sector facing serious labor shortages in Austria.

Musa had “done everything in his power,” Helena and Jonas told me, to prove he was worthy of receiving legal status in Austria. But, after all of that effort, the Austrian government had decided Musa did not deserve a protective status. The reason the authorities gave, in a nutshell, was that Musa belonged to Pakistan, a “safe country of origin.” Nor did they want to issue him a work visa, since he purportedly tried to exploit their asylum system.

Musa was now a “fully integrated Austrian,” Helena and Jonas said—an Austrian “that Austria needs but does not want.”

What had led to these dire circumstances?

In order to understand why Musa was seeking asylum, it’s important to know more about the place Musa came from: the Khyber District (formerly Khyber Agency) along Pakistan’s border with Afghanistan.

Until recently, this district was part of what’s called the Federally Administered Tribal Area (FATA)—described as a “no man’s land” by Talat Masood, a retired general of the Pakistan Army turned political analyst. Ever since Pakistan gained political independence in 1947 with the end of the British Raj’s rule over India, this area has been severely neglected by the state.

The area and its people were exploited during the Soviet-Afghan War in the 1980s and then subsequently during the United States’ “War on Terror” led by then-President George W. Bush’s administration after 9/11. Since 2014, the Pakistani military has been leading offensive strikes to clear out banned militant outfits, including the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), Daesh (ISIS), and Al-Qaida, among others—groups that started to dig in their heels in Pakistan after their downfall in Afghanistan in the early 2000s. In 2018, the government of Pakistan finally merged FATA into the Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa province, purportedly to stabilize this volatile and geopolitically significant region.

The Pakistani military is currently carrying out its third operation in the Khyber District. Known as R’add-ul-Fasaad (رد الفساد in Urdu), literally “elimination of strife,” the government claims it will be the last of several consecutive military operations carried out since 2014.

Some peace has finally been achieved in the region—but the years of conflict between armed groups and the Pakistani military have cost lives and destroyed homes, schools, roads, and other crucial infrastructure. Since 2008, this multifaceted conflict has internally displaced more than 5 million people.

This brings us back to Musa, who would have either become one of those millions of internally displaced people or, worse yet, killed, had his father and uncle not arranged for him and two of his brothers to flee the country.

At around age 14 or 15, he set out on a difficult journey from Pakistan through Afghanistan, Iran, Turkey, Greece, and finally, Austria. An agent hired by his uncle and father had initially instructed him and his brothers to carry on to Germany. But Musa lost his brothers along the way, after several months following the infamously dangerous Balkan route on foot.

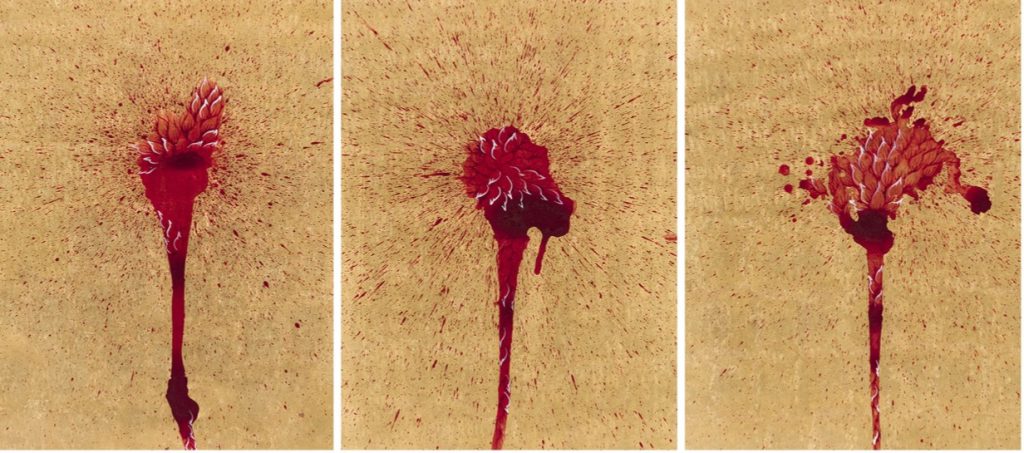

Most of my interlocutors come to Europe along this route, so I have heard about the horrors they encountered on their clandestine journeys, such as waiting in the scorching desert heat or on freezing mountain passes to cross the barbed wire border walls at the right time, when patrols were busy or absent. If spotted by border guards, they could have been severely beaten and faced “push-backs,” where they could have been illegally forced to cross back over the border. Sometimes, migrants are shot at and killed by authorities.

One of Musa’s brothers was caught by border guards in Iran and the other in Turkey, and both were deported to Pakistan soon after. By the time Musa made it to Austria in 2015, alone and exhausted, he had trekked across mountain passes, crawled into secret bus compartments, and gotten crammed into the trunks of several vehicles. Having lost the will to go on any farther, he handed himself to the Austrian police and asked for asylum.

If Musa became a “good Austrian,” thought his hosts, then why would someone deny him the right to stay in the country?

Once in Austria, different kinds of challenges presented themselves to Musa—perhaps not as dangerous or immediate as the risks he faced on his journey, but no less daunting. He had to navigate the European asylum system at 15 years of age with only a Koranic education—the only form of education people in his village had access to when he was growing up there. And living in refugee accommodations meant that he had little contact with Austrians.

Once he moved in with Helena and Jonas, his social life and mental health took a turn for the better. His legal status was the only issue at that point.

After Musa had been denied asylum several times, Helena and Jonas started losing faith in the asylum system. Integration was not enough to guarantee Musa a safe home in Austria, they realized.

At the most recent hearing they had attended, Helena and Jonas felt some of the judge’s questions appeared biased and that she hardly attempted to understand Musa’s situation or Pakistan’s sociopolitical context. Instead of appreciating Musa’s efforts to integrate and educate himself, the judge questioned Musa’s claim that he had only received a Koranic education in his youth. The judge also indicated that Musa belonged to a “safe country” where any person could receive a proper education.

“We are convinced of Musa’s unfair treatment by the judge and the verdict’s arbitrariness,” Helena and Jonas wrote me. “The court hearing was (in our opinion) a farce.”

I was deeply touched by Helena and Jonas’ compassion for their guest, who had now become part of their family. While I could give them little advice, I put them in touch with family friends who work for the European Commission and who were kind enough to offer their support. While I knew that Pakistanis in Musa’s situation usually resort to migrating again without documents within Europe to avoid deportation, I discouraged them from taking this path because of the dangers it would pose to Musa, who has already seen so much suffering.

That then left Musa with only one option: accepting the Austrian government’s demand and returning to Pakistan “voluntarily.” This would, in theory, enable him to apply for a work permit in Pakistan that would allow him to return to Europe through more formal channels.

That said, having had experiences with several European consulates in Pakistan, I knew that getting a European visa would not be easy.

Transnational mobility is relatively manageable for Pakistanis from privileged classes or those in specialized fields, like me, who are categorized as “highly skilled.” However, the average Pakistani faces “endless waiting and humiliation in consulates” due to the bureaucratic traps that manage migration, to use the words of the philosopher Achille Mbembe. In fact, echoing the racist colonial past, most European embassies in Pakistan are located in a place called the “diplomatic enclave” in Islamabad, where Pakistanis cannot even enter without an appointment.

Despite these unjust circumstances, however, Helena, Jonas, and Musa’s story might turn out to have a happy ending after all. The last I heard, after sending out many emails, they had finally heard from a high-ranking official at the Austrian Ministry for European and International Affairs. He informed them that Musa would have to go back to Pakistan but his legal return to Austria would be made as smooth as possible. Helena and Jonas told me that this person not only promised his support to Musa but was the most empathetic official they had talked to thus far—restoring some of their trust in the Austrian state.

Only time will tell how Musa’s fate unfolds in Austria. But unless there are systemic political changes to the immigration system, most asylum-seekers and migrants will continue to face an uncertain future, especially those without the support of compassionate people like Helena and Jonas.

Correction: June 2, 2021

An earlier version of this article inverted the Urdu phrase. In addition, it erroneously referred to “a family friend” in the singular rather than “family friends.” The text has been updated accordingly.