How to “Co-Live” With a Natural Hazard

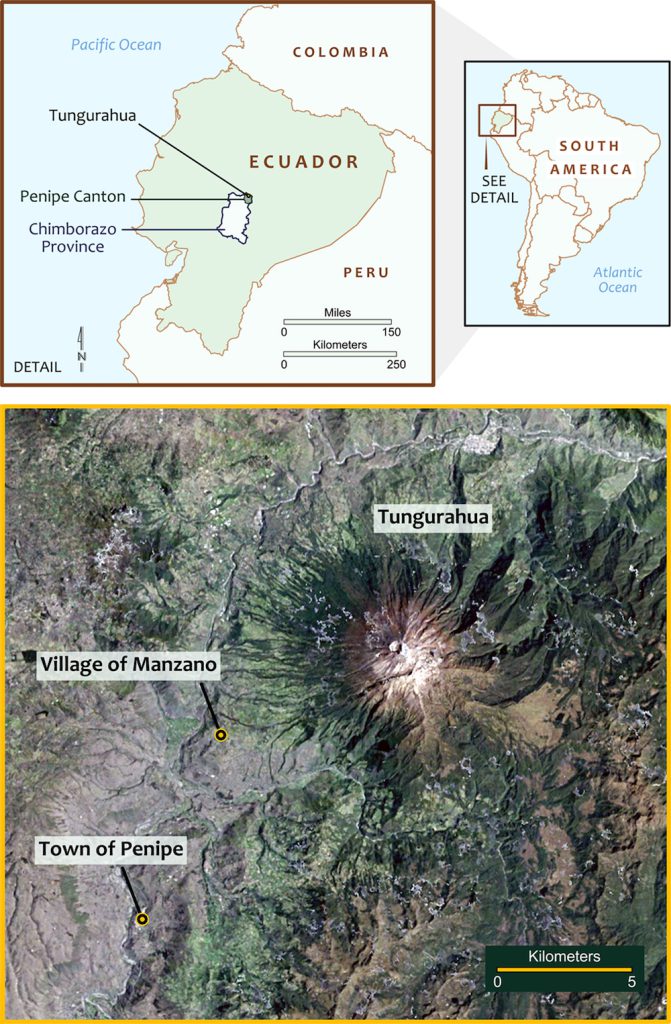

As the Andes mountain range curves through Ecuador, it rises to the peak Tungurahua. The name comes from the Kichwa language, spoken by some of the Indigenous communities of Ecuador, and means “Throat of Fire,” which is fitting for a volcano that towers more than 5,000 meters into the sky. It’s been active over the past 20 years or so, resulting in spectacular displays of flying lava and ash.

But some residents of Penipe Canton, the territorial district that borders the volcano, give Tungurahua another name: abuela, Spanish for “grandmother.” They see the volcano as a familiar, if fiery, matriarch. They live and farm in villages dotting the steep slopes—just as generations of their families have done before them—and wouldn’t dream of living elsewhere.

It’s a perspective that puzzles outsiders. In 2011, when anthropologist A.J. Faas attended a meeting between people displaced by the eruptions and canton leaders, he was not anticipating an impassioned plea to return to their still-smoking lands.

Faas had tagged along with Pablo Sánchez, a farmer and long-running president of the village of Manzano, who listed many grievances to regional officials. But Sánchez’s top priority took the officials by surprise too. He asked them to lift a “high-risk” label on the canton of Penipe, which includes Manzano and other volcano-rimming communities. With that designation, Sánchez complained, it was impossible to obtain aid and credit to rebuild the area and move back home.

“The government officials were positively perplexed,” recalls Faas, who works at San José State University in California.

So was Faas, though he’s no stranger to natural disasters himself. This fall when San José was bordered by wildfires, he didn’t have to evacuate but took it as a reminder to update his earthquake go bag.

Faas originally went to Ecuador to study the displacement and resettlement related to the volcano’s recent eruptions. Unexpectedly, he discovered a story of resilience, including ways locals frame their relationship with circumstances outsiders find terrifying.

Their approach could hold valuable lessons, particularly in the value of giving local communities agency to respond to disasters—whether a pandemic, social unrest, fires, or floods—rather than imposing solutions from the top.

“The volcano is not a terror,” says Sánchez. (Sánchez, like many residents of Penipe Canton, speaks Spanish, and Faas served as an interpreter.) “Our generations are prepared for the next eruptions that could come.”

Indeed, Sánchez and many others fully expect Tungurahua to erupt again, though they can’t guess when.

Leading up to the turn of the 21st century, Tungurahua had been silent for some time. The mount’s last major eruption spewed hot rock and gases from 1916 to 1918. By the 1990s, some villagers say their communities had forgotten the signs of impending activity and appropriate responses to eruptions.

They were violently reminded in 1999 when Tungurahua blew its top. For years, the eruption continued, spewing a column of ash 3,000 meters high and catapulting rock fragments onto nearby villages and agricultural fields.

Roughly 6,500 people were displaced, some forcibly removed by the military and police. Evacuees sold livestock and potatoes that they’d brought from their homes at rock-bottom prices. Some spent years in improvised shelters, such as church basements or schoolhouses. Others migrated to cities.

By the end of 2005, as the volcano seemed to calm, about 3,000 people had returned home. But in 2006, Tungurahua erupted even more violently, twice, displacing them for a second time. Between the two eruptions in July and August that year, many people resisted leaving, building camps just below their villages, but they were permanently barred from returning by the Ecuador Secretariat for Risk Management.

The government and nongovernmental organizations, rather than invest in redeveloping the areas closest to the volcano, began to build new settlements, 10 kilometers or more away. It was these changes that drew Faas to the region for the first time in 2009.

Eventually, 287 households relocated to the town of Penipe, the canton’s capital, with no space to farm. Others landed in the 45-home settlement of Pusuca, where they were granted a half hectare each. Much was forested and difficult to cultivate, and irrigation wasn’t completed until 2013.

Accustomed to raising much of their own foodstuffs, the evacuees struggled to adapt to a solely buy-and-sell economy. The government tried to help by offering to trade new land elsewhere for volcano-based farms, but villagers resisted, Faas says. “People thought that they were trying to rob their culture and their heritage out from under them.”

The evacuations and resettlements had more impact than the actual eruptions. “The city, for them, was as dangerous or more so than the volcano,” Faas explains.

In fact, by 2009 many volcano denizens made regular trips home, even just to tend their farms during the day, despite the ongoing rain of ash that filled their lungs, blighted their crops, and sickened their farm animals. By 2011, when they petitioned officials to remove the “high-risk” label, they still longed to return permanently.

And around 2013, Faas began to hear locals use a new term—convivir—describing a manner of “living with” the volcano and neighbors despite the risks perceived by outsiders. With Tungurahua going dormant in 2016, they’ve returned to the slopes to put the idea into practice.

Those living around the volcano use the term convivir to describe the way they adapt to their volatile neighbor while maintaining their way of life. Though it’s often translated as “coexist,” Faas prefers the literal “co-live.”

To convivir with a potential hazard, in the way Tungurahua’s human grandchildren do, describes a complex concept. “It’s a metaphor, and it’s a political project, and it is a set of activities,” Faas says. The approach encompasses everything from evacuation drills to improving soils covered in ash. Growing food, tending animals, and rebuilding infrastructure on the volcano’s slopes all count. Community cooperation is a big part of it, Faas says.

Convivir allows the villagers to keep their home. “That’s everything that matters to them,” Faas says. “They are as attached to it as they are to each other.”

“They know a ho-hum, daily explosion from a ‘Holy sh*t, get out of here!’ explosion,” says anthropologist A.J. Faas.

Most importantly, locals recognize the volcano as a part of their community, even calling it abuelita, a term of endearment. Today’s villagers note that their parents called Tungurahua mamá, but as that generation aged, their powerful neighbor gained a more mature title. (Traditional belief holds that Tungurahua is the female partner of a neighboring volcano.)

Villagers have worked with the government and other agencies to prepare for future eruptions. In collaboration with the Ecuadorian Geophysics Institute at the National Polytechnic School in Quito, they monitor abuela for signs of impending eruptions.

The institute uses seismometers to monitor earth movements associated with eruptions, but a local network of several dozen vigias, or “watchers,” also contribute a deep understanding informed by their long familiarity with their volcano. As Faas puts it: “They know a ho-hum, daily explosion from a ‘Holy sh*t, get out of here!’ explosion.”

These local watchers use radios to communicate with one another and the Geophysics Institute, and they stand ready to warn villagers if they might need to flee. Should that happen, residents are prepared. In collaboration with the Secretariat for Risk Management, they’ve run evacuation drills.

Kate Browne, a cultural anthropologist at Colorado State University in Fort Collins who also studies the social changes and cultural knowledge involved as communities adapt to disasters, says the convivir concept is “very provocative and fascinating and important.”

One lesson she draws from Faas’ observations is the benefit of empowering people at the local level, rather than focusing on solutions imposed by the government. Faas and Browne believe approaches that give agency to locals are most effective. “If there’s one thing that anthropologists have learned,” Browne says, “we all share this recognition of the incredible importance of agency.”

For example, the troubled relocation effort In Penipe Canton illustrates the limits of top-down solutions that lack local insight. Another example comes from a government-led scheme to encourage farming of ash-resistant white onions on Tungurahua’s slopes after the 2006 eruption. The move resulted in an overabundance of the pungent vegetable, flooding the markets such that much of the crop rotted, uneaten.

Browne observes that the importance of local agency is relevant to many disaster-struck communities around the world. She recently made a case for the importance of local knowledge and cultural awareness in planning recovery efforts to representatives of the U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency.

“When outsiders recognize local people as collaborators, and when local groups are able to exercise more control,” Browne asserts, “they recover faster and more fully.”

The year 2020 gave the world a surfeit of disasters, both natural and human-made. The COVID-19 pandemic has created something else Penipe’s villagers must co-live with. As of early December, says Sánchez, two people from Manzano—which has about 50 households—had fallen ill. Both were hospitalized but later recovered.

The buses stopped running for a period during the pandemic, making it hard to obtain needed supplies such as fertilizer. In response, the people of Manzano, Sánchez says, put faith in God and their communities. “We have to take care of ourselves, in one way or another,” he says. For example, to replace the buses, Sánchez himself taxied villagers in his pickup truck.

Faas has built a kinship with the villagers as well and has helped with building projects and attended community meetings. (Sánchez affectionately nicknamed him Gringo Loco—“crazy gringo”—for his eagerness to participate in village life. In another village, Faas goes by El Pollito—“the little chicken”—in reference to his dancing style.) In response to the coronavirus, Faas worked with locals to arrange care packages with masks and household staples. Tears spring to both Faas’ and Sánchez’s eyes as Sánchez expresses how much the villagers miss Faas and appreciate his efforts.

And as always, Penipe’s excitable grandmother looms large. Many locals believe their monitoring system and evacuation preparedness will allow them to keep their homes while protecting them from inevitable future volcanic activity.

They’re living where they want to live—and when visitors jump at abuela’s every burp or sneeze, the vigias laugh wildly in response.