The Casual Menace of a Trump Rally

Thinking back, I have to say, the popcorn and lemonade were among the strangest things about the Trump rally I attended in December 2016. Not that there was anything unusual about the concessions. Salt, fat, and sugar were as ample as at any American sporting or stadium event. That, though, was exactly it. As a newcomer to this scene, the banality is what stood out to me.

Get in line, put in an order and fish out some bills, find a seat in the stands, and pass the time until things get going: What could be more ordinary?

Like so many others, I was thrown by the outcome of the presidential election that year. My social circles were progressive, left, and liberal; like most everyone I knew, I felt that something monstrous and unfathomable had happened. But the ethnographer in me was twitching with questions. I realized that I didn’t understand the country where I’d lived nearly all of my life, and I felt compelled to try.

After the election, president-elect Donald Trump held victory rallies around the country for his supporters. As an Indian American and the father of two young children, I found it a fearful and dispiriting time; hate crimes had spiked in the days and weeks after the election. Nonetheless, I decided to attend a rally in Hershey, Pennsylvania. By trying to watch and listen with an open mind, I thought I could help figure out how we in the U.S. got to the point of electing Trump.

I came away unscathed that night, but I remain disturbed by the experience. I saw firsthand how friendly and innocuous banter could meld with a harsh and menacing politics. Over the past four years, this mixture of overt hostility and good cheer has seeped into many corners of daily life in the U.S. Rooting out this everyday aggression will take time.

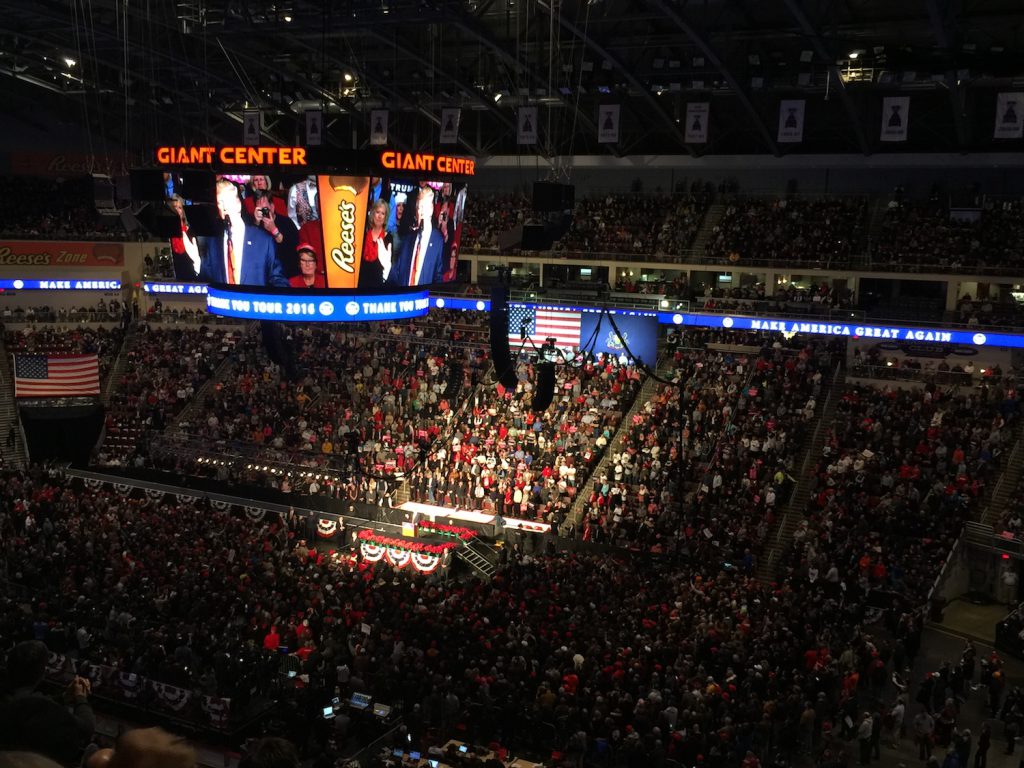

The bitter cold stung my face that afternoon as I drove to Hershey from Baltimore. My compact hatchback looked out of place among the pickup trucks jamming the lot at the Giant Center, where the rally was held. The line of people waiting to get in stretched around the arena, with some people standing for hours in the frigid air for a chance to sit near the stage.

Men and women of all ages, shapes, and sizes gathered in the queue, as if it were a line for a concert or a ballgame. Of the hundreds of people I passed by—folks in sweatshirts and team jackets, older people in wheelchairs, and kids toting backpacks—all but a handful were White.

In the wake of the 2016 election, I had started doing research and fieldwork in conservative American circles. I began reading the right-wing Breitbart News site and tuning into my local conservative talk radio station, WCBM, but my bids for conversation with people whose views differed from mine were still pretty weak.

In line for the December rally, one man frowned skeptically at me when I tried to bring up what political commentator Sean Hannity had said on his radio show that afternoon. I may have been too earnest about passing.

I realized that I didn’t understand the country where I’d lived nearly all of my life, and I felt compelled to try.

As the line edged closer to the door of the arena, I overheard a young guy chuckling with a friend about a trip to Philadelphia, where he had flashed a man who approached his truck with the .45-caliber handgun he kept concealed in the glove compartment. I felt both horror and fascination at the laughter and bravado in his tone, as if he’d pulled off a good prank.

As I started talking with the two of them, our lives converged unexpectedly. It turned out that the guy who told the story was an accountant, and his niece was a student at Johns Hopkins University, where I teach. It happened that she was studying archaeology and doing fieldwork in the Middle East. “Small world,” he kept repeating, and I had to agree.

Once inside the arena, with popcorn and lemonade in hand, I had to find a place to sit. That felt daunting. I couldn’t help but think about how I looked: in an ordinary black jacket and hoodie, but also alone with a dark face and black hair. Time and again throughout the campaign, and especially in the weeks after the election, people who looked like me—people born in the U.S., like I was—had been told by Trump and some of his supporters to get out of the country.

I braced myself for the possibility that I might encounter such hate. One man told me flatly that the empty seat beside him was taken. Higher up in the stands, a taciturn man in an American flag–patterned shirt seemed more indifferent to my company. I squeezed in between him and a middle-aged woman with spectacles.

Laura (a pseudonym) and I fell easily into conversation. She told me she had just retired from working at a pretzel company and planned to move soon to a second home in Florida. She explained how wet the soil was in that coastal area, how she and her husband had to keep the pool filled with water or it’d pop right out of the ground. (Later, I wished I had asked her what she thought about climate change.) Her husband, farther down the aisle, was crazy for Trump, she told me.

“What about you?” I asked.

Laura said she wasn’t sure about Trump’s ideas, but she didn’t think he’d follow through on all of them. She hadn’t trusted the Democratic nominee, Hillary Clinton, in any case.

The couple sat with a friend of theirs who worked at the University of Pittsburgh, and they were all surprised to hear that I taught at Johns Hopkins. They were amicable, passing me a “Make America Great Again” sign, which I accepted politely.

“I don’t know if you voted for Trump,” Laura observed at one point, which meant I had to account for why I was there.

I admitted that I hadn’t voted for him, adding that I’d come to the rally because I was curious. My thoughts flitted between those of a deeply troubled citizen and an anthropologist at work—torn between critiquing a noxious politics and immersing myself in a culture foreign to me.

Over the past four years, this mixture of overt hostility and good cheer has seeped into many corners of daily life in the U.S.

I didn’t know how to act. A year later, I would spend a day at a “White Lives Matter” rally in Tennessee, engaging in long and avid debates with White nationalists. But in 2016, I didn’t have a feel yet for how to pursue such fraught conversations. When everyone stood up at the Trump rally to cheer and clap, I stood and halfheartedly waved my MAGA sign along with them.

I cringe now when I think back to that moment. I didn’t attend the rally to protest it. I wanted to grasp the appeal of Trump’s politics and try to understand how he had won so much support. Still, one might see complicity in the gesture that I made, caught in the uncertainty of how to be there—and also by feelings of shame and unease.

Someone a few rows below us took a photo of me with that sign, and we made eye contact. That man may still have an image of that awkward moment.

The stands were nearly full. Waves of enthusiasm coursed through the crowd while we waited for the newly elected president to appear on the dais. People chanted, “U.S.A.!” and “Build. The. Wall!” The song “Proud to Be an American” played more than once.

Without a doubt, Trump was good with a crowd like this. After he stepped up to the podium to speak, I could feel the tides of emotion ebb and flow as he shifted register between raucous declaration and light-hearted banter. He promised “the wall” with Mexico, fewer refugees, and an end to nation-building in places “you’ve never even heard of.”

Cruelty finds harbor in the most banal of circumstances.

He also decried journalists, calling them “absolutely terrible, terrible, destructive people.” I looked below and wondered how the reporters penned in on the arena floor felt, drawing loud boos and jeers from the gallery of thousands above them. It had to feel somewhat terrifying.

Trump spent a lot of time recounting the twists of the election night returns. I found it hard to stomach his reminiscing, as that had been a crushing evening for those of us looking to welcome the country’s first female president. I wasn’t a Democratic Party loyalist. But Clinton at least was willing to affirm the needs of Americans left out of the national story.

Trump went on to goad the crowd. “Before the election, you people were like wild beasts, wild animals,” he recalled. “You were like crazed people, and that’s good. I like that. And now, no, you’re laid back,” he trailed off, almost wistfully. “You’ve won, and you feel great about it. And you don’t have to go totally wild, right?”

On cue, a boisterous chant surged through the stadium: “U.S.A.! U.S.A.!”

“My message tonight is for all Americans from all parties, all beliefs, all walks of life,” Trump said, closing out the night. Then he added, with a bit of a snarl, “Whether you’re African American, Hispanic American, or Asian American, or whatever the hell you are.”

People laughed. That he meant something other than what he said was patent.

Who would find themselves represented by that phrase, one among the whatever the hell you are? Trump had to be talking about people who weren’t in that arena.

His message took me back to something that had happened in the bathroom earlier that evening. As I had washed my hands, I overheard a tch of disdain. “We Republicans treat all people with courtesy,” one man said to another, in a loud, slow drawl.

The man’s tone felt menacing. I didn’t have it in me to turn my head and look him in the face. But my mind raced with the possible implications:

You’re no Republican, like we are.

We’ve been courteous, but we don’t have to be.

Your people aren’t our people.

You don’t really belong here.

This is a warning; next time, you may not get one.

So many possibilities. All except for one: You’re one of us.

When the rally ended, I bid goodbye to Laura and the others, and stood up to shuffle slowly with the crowd down the stadium stairs. People were mostly quiet, as if they remained absorbed in the spectacle, as if it had been a movie, game, or show whose excitement would ebb only gradually.

In some ways, I think all of us in the U.S. are still shuffling down those stairs, unsure of how the world will look when, bleary-eyed, we finally reach the outside once again.

That moment will be a cold night, whenever it comes. But the end of the Trump era, which I hope comes sooner rather than later, will also be a chance to meet strangers anew with genuine warmth and hospitality. What will we say—and what will we do—when we find them beside us?

It’s become too easy for many of us in the U.S. to shrug off the suffering of others. Cruelty finds harbor in the most banal of circumstances. Indifference is a habit we will need to unlearn.