Transracial Adoption and the Limits of Love

On a Saturday morning in downtown Kampala in 2020, I stood on a busy sidewalk in front of a store. As I waited for a friend who was inside shopping, I daydreamed about my son. My husband and I had celebrated his second birthday just a few days prior, and as we approached the 10-month mark of living in Uganda, I realized he had spent nearly half of his life in the field with me. Our life in Kampala was all he knew.

My reverie abruptly ended when I realized I was slowly being surrounded.

Nearby, a man was gathering a crowd and loudly admonishing President Yoweri Museveni for allowing “the Chinese” to stay in the country. He encouraged the crowd to take matters into their own hands when they saw a “Chinese” person. All eyes turned on me.

Thankfully, Sam, my motorbike driver turned trusted friend, was waiting nearby and acted quickly when he saw what was happening. He rushed over, pulled me onto his bike, and drove off as people chased after us screaming, “Coronavirus! China virus!”

It was March, and then-President Donald Trump had just declared a state of emergency in the U.S. over the COVID-19 pandemic. It was on the cover of every newspaper.

Since arriving in Uganda to conduct anthropological fieldwork the year before, my racial identity as an East Asian woman had elicited curious questions about my origins. But when Trump began his campaign of xenophobic verbal assaults blaming the pandemic on China, my identity was decided for me: I was “Chinese,” and I was COVID-19 incarnate.

Suddenly, I realized we had to leave the place my son considered home.

As a Korean adoptee who was raised by White parents alongside their biological son, this period in Kampala was hardly the first time I was marked as different.

Though my hometown is in Central Massachusetts, far north of the Mason-Dixon line, Confederate flags have been flying there since I can remember, signaling to outsiders who belongs and who doesn’t. Growing up in this politically conservative, semirural town that was 97.93 percent White (as of the 2000 census), my racial identity was a constant source of consternation. Yet the harmful effects of growing up in this racist environment were purposefully ignored by my well-intentioned parents.

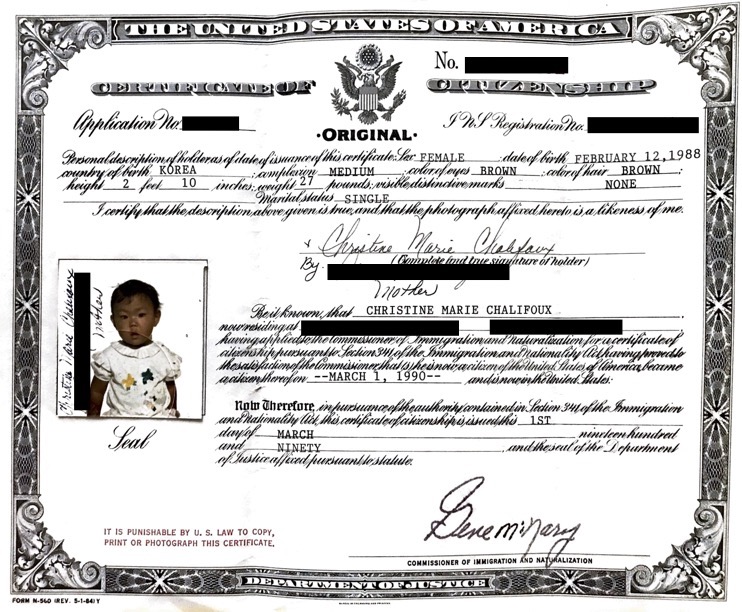

When my parents adopted me in 1988, Korean adoptees had been entering the United States for more than three decades. The complex reasons why South Korean children came to be adopted widely by White parents have to do with broader forces of race relations and U.S. militarism and imperialism.

For one, the legalization of abortion in 1973 in the U.S. created a shortage of White children available for domestic adoption. This was coupled with heightened scrutiny of White parents who adopted Black children without recognizing or meeting their specific cultural and social needs. White U.S. couples looking to begin or expand their nuclear families through adoption, like my parents, found a solution to this problem in Asia—and particularly South Korea.

After the Korean War (1950–1953), the country had started sending unwanted “mixed children” born to Korean women and American soldiers abroad as an emergency measure. As anthropologist Eleana J. Kim has shown, this decision to export “illegitimate” and poor children continued long after the war’s end, largely as a way to absolve the government from creating social welfare nets to care for the most vulnerable in South Korean society.

The mostly White U.S. social workers who facilitated the adoption of Korean children into White families like mine pushed a colorblind approach to raising children. Influenced by faulty ideas about biological race hierarchies, they believed the differences between White parents and Asian adoptees were not as great as with Black adoptees, and as such, they could simply be ignored. That meant White parents could go through the entire adoption process without learning the Korean language or the country’s cultural nuances. Agencies even arranged for Korean babies to be flown into the U.S. with chaperones so that adoptive parents never had to leave the country.

This colorblind approach had lasting consequences. In her ethnography on South Korean adoptees, Kim explores the refusal among White adoptive parents to recognize race. The adult adoptees in her book desire to return to Korea and find people who share their racial identity—despite their families’ dismissal of their differences. Many Korean adoptees, such as intercultural studies scholars Tobias Hübinette and Kimberly McKee, have written extensively about how growing up in all-White spaces and having their race ignored affected their sense of self and left them ill-prepared for racism they faced.

For some Korean adoptees, this racism begins even within the supposedly protected family space. My brother still jokes about pretending to be Rambo when we were children, tying me up and calling me Vietcong. A face like mine in an all-White space could stand in for multiple racist tropes for his amusement: a Southeast Asian terrorist, a generic Asian nerd who must be “naturally” good at mathematics, a Chinese communist spy.

My family, of course, vehemently denies this behavior was harmful. After all, since I was not recognized as being different, then how could such “teasing” possibly be racist?

After a childhood spent roleplaying Rambo, my brother grew up to become a soldier. The heightened militarism in post-9/11 America elevated his status to hero, and I juggled a great deal of guilt. Rather than loving my brother because of his military service, I found myself loving him despite it.

I never openly criticized his decision to enlist in 2006, but I forged a different path for my own life: I moved away from my small town to attend college in New York City. I wore my leftist politics on my sleeve. I found my voice and used it, unafraid of challenging my family’s conservative politics.

Yet, when my brother’s infantry regiment was deployed to Iraq, I worried about his safety every single day with a fervor that one reserves only for those dearest to one’s heart. Much to our whole family’s great relief, he returned from his tour in Iraq physically unscathed. But our ideological divide continued to grow as our lives returned to normal.

Soon after his return, I graduated from college and enrolled in a master’s program in anthropology. It was then that I began to read texts that challenged everything I had taken for granted about kinship, family, and adoption.

If we are to remain kin, love is not enough.

I learned that others questioned the “benevolent” beginnings of transnational adoption, and that using children of color as a shield from accusations of racism was a common phenomenon among adoptive parents. Equally common was the mixture of guilt and anger adoptees felt at witnessing their families’ bigotry.

I also started to realize how, when Asian adoptees like myself got absorbed into White families, we became living examples of Asians’ proximity to Whiteness. In the process, transnational adoption from Asia to the U.S. helped perpetuate the model minority myth: a set of stereotypes that labels Asians the “good” minority group and pits them against Black Americans—while ignoring institutionalized racism and the history of xenophobic attacks faced by Asian Americans. This myth helps those in power maintain an order of white supremacy by making it more difficult for communities of color to form political solidarities.

As I was delving into anthropological texts, my brother’s unit was sent to Afghanistan. This time, he was seriously injured in a roadside bomb attack in 2010 and spent nine months recovering at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, D.C. After many surgeries, tears, and hours of rehabilitation, he returned to our hometown to a hero’s welcome—complete with a police escort, a parade, and yellow ribbons tied to every utility pole.

I always felt suffocated by my hometown, and when I returned to see him after his release from the hospital, it was no different. But this time, I watched the same people who had used terms like “chink food” in front of my face do remarkable acts of kindness for my brother.

As he continued to recover, I became increasingly angry when I thought about our relationship. My brother could continue to openly joke about my race, something over which I had no control, but I could not dare question U.S. empire or the so-called war on terror because of the choice he made to enlist in the military.

I was supposed to grin and bear it—because, after all, we were family.

Anthropologists have shown that there is not a universal definition of kinship. But with DNA testing and popular media like Who Do You Think You Are?, a genealogy documentary TV series, many people in the U.S. and Europe continue to think of family as a set of people who share biogenetic substance. Adoption challenges such a notion by creating families across racial, ethnic, and national boundaries.

For many adoptees, being integrated into a nuclear family offers the love and support that we often take for granted as part of kinship. But, as anthropologists Sharika Thiranagama and Tobias Kelly have shown, intimate relationships are especially subject to threats of betrayal. If families are supposed to provide unconditional support, not receiving such support cuts that much deeper.

On that surreal afternoon in Kampala, I arrived back home to my new nuclear family: the kin I chose when I got married and had a child. Grateful is not an adequate word to describe what I felt for my husband and son that day.

Later, friends in Kampala called us to report other incidents targeting Chinese and Chinese-looking people, confirming I was no longer safe in the city. My husband packed away as many of our belongings as would fit into our two large suitcases. Devastated, we left Kampala within 36 hours.

On the long journey home, I began to think about the family in which I was raised. I wondered if they could believe that my race made me a target in ways that they would never experience.

The anti-Asian hate unleashed by the COVID-19 pandemic over the past two years has been yet another reminder that I am not like my family, regardless of how much they insist that I am. It’s also brought home how their political beliefs as Trump supporters actively harm people who look like me.

I still love my family, my brother included. And I know that they love me. But, if we are to remain kin, love is not enough.