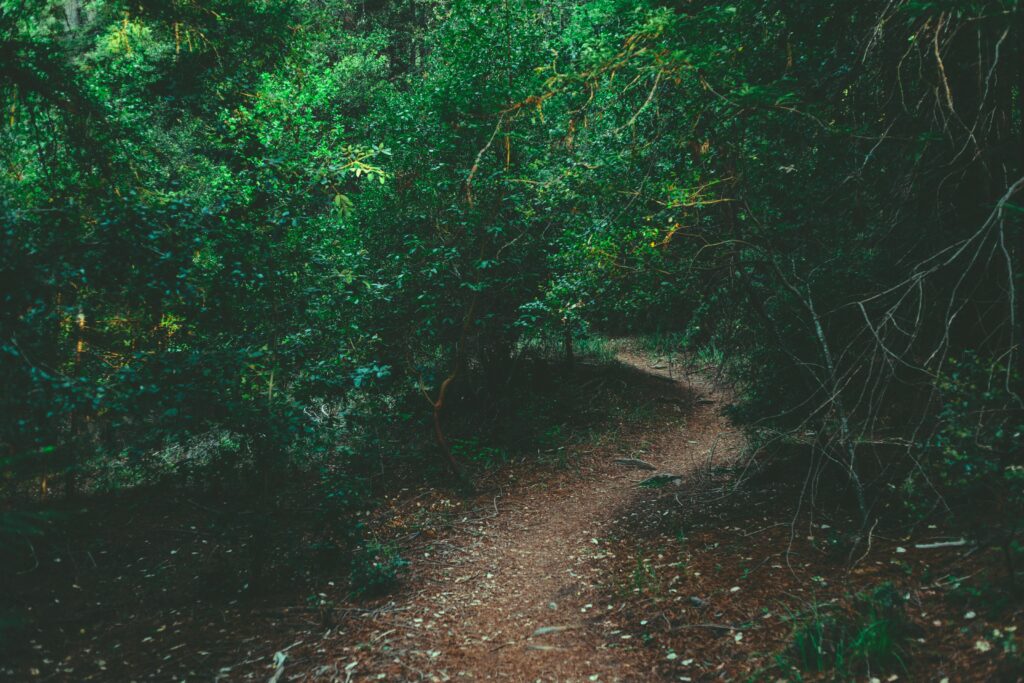

The Path

“The Path” is part of the collection Indigenizing What It Means to Be Human. Read the introduction to the collection here.

You went farming in the Whiteman’s land

A sapling, a foal with wobbling feet

And now you return with the Whiteman’s tongue

A blossomed nkeng, a mare in her prime

[1]

[1]

Nkeng is a type of dracaena plant, usually called the “peace plant” in the northwestern grass fields of Cameroon.

And you ask their questions

Questions asked of my mother’s mothers

Questions that filled us with terror

Because the shadow of the master hovered over their shoulders

As they sought, and probed, and queried

And so, the secret of the owl sacredly hidden from daylight was divulged

But this knowledge became the yoke that bound us to misfortune

Our language, dress, customs they declared taboo

And now to see my very own, my seed, pursue this path!

I remember as a little girl, the White woman with the helmet

Who wore trousers and boots like the masters

And stared men straight in the eye

She said she sought to understand our ways

To know why when the Fon was lost

[2]

[2]

Fon refers to a traditional ruler believed not to die but to become “lost” through passage to the world of the ancestors.

Men would take off their caps, beat their chests, and sigh

While women tied their loincloths at the waist

Baring their proud breasts, ululating their grief

And so, our mothers and aunts and grandmas

Whispered words of tradition, entrusting our lifeline to her

But the essence of our people became the tool of their subjugation,

“Fons and chiefs!,” they cried, “Rule them through these men they so respect!”

Wulililililiy, abomination!

[3]

[3]

Wulililililiy is an exclamation of incredulity, anguish, and sometimes even wonder. It signals something out of the ordinary.

And now to think that my very own, my seed, pursues this path!

When I think of you, my child, my heart severs within my chest

Through no fault of yours you were born into these times

You could not run from the storm of this changing world

This limbo, where forgetting is as painful as remembering

And memory dances to the beat of the njang in our bone-weary bodies

[4]

[4]

Njang is a traditional dance common among some ethnic groups such as the Noni people in the northwestern grass fields of Cameroon.

But, my descendant, of all you could have studied, why this route?

Is this not searing betrayal, siding with that which oppressed your own

And from which our elders fought to break free with blood, and tears, and sweat?

Are you truly one of us, my offspring, or are you one of them?

Where do you belong? Who really are you?

Was there no way that my very own, my seed, could have escaped this path?

I hear you respond, “Bwan, I may speak the Whiteman’s tongue now

[5]

[5]

Bwan is the word for “mother” among the Noni people.

I may have acquired their ways and ask their questions

But I know where my umbilical cord is buried

Yet do not ask me who I am for I cannot say

The fabric of my life is woven with many colors

Its aesthetics cannot be reduced to a single version

And in this in-between where I negotiate my identity

And navigate the stormy seas of representation

Bearing the weight of my lineage upon my shoulders,

One thing remains certain: I am in a state of perpetual becoming

And within this space where past and present marry,

I emerge as a child of both and yet of neither, the proof of an uncharted future

But Bwan, isn’t it proper that the so-called Other document their own ways?

Isn’t it laudable that now the gazed at has become the gazer?

Isn’t it empowering that I can revisit and rewrite

Showing who we are, not who we ought to or were told to be?

And so, isn’t it fitting that your very own, your seed, should pursue this path?”

When you speak like that my child, I do not comprehend fully

But because your roots are sunken into our soil

Because our truth is buried deep in your bones

Because you, the little bird we sent forth, have grown potent wings

I welcome you back even as I wonder where “home” is for you

But I find consolation when you tell me,

“Bwan, I am an anthropologist

Yes, its sordid past as colonialism’s enabler remains

But I have safeguarded the fimbiw you passed down to me

[6]

[6]

Word for “kola nut” among the Noni people.

Entreating me to keep the cycle rolling

And now if I engage with my own through the eyes of my clan

Guided by the wisdom of my ancestors,

Then I can not only come home but take home with me—

History will not be told only from the victor’s viewpoint anymore

The lions have learned the hunter’s tongue

And will use it to sing their chorus

And so, Bwan, your very own, your seed, has indeed chosen to pursue this path!”