The Cultural Anxieties of Xenotransplantation

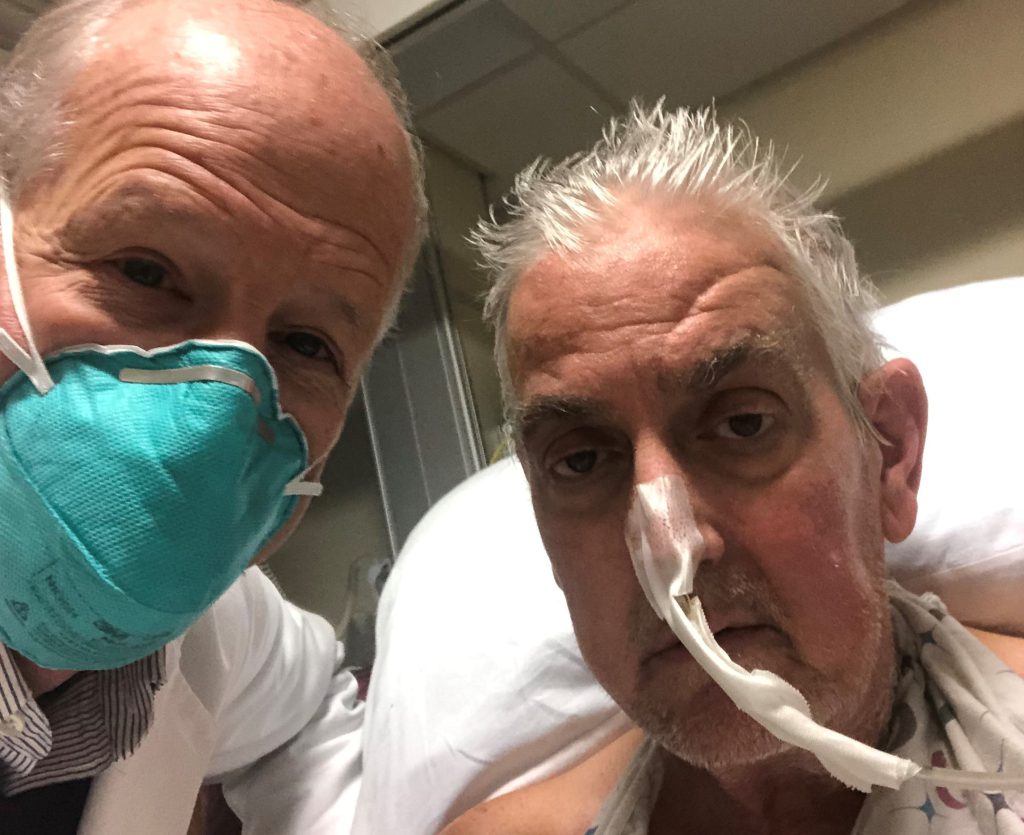

In January, news broke that David Bennett Sr.—a 57-year-old man with a serious heart disease—received a heart from a genetically modified pig. The eight-hour operation, which took place in Baltimore, Maryland, was deemed a success.

Medical doctors hailed the operation. Human-to-human heart transplant has always been a rare, expensive, complicated procedure due to the shortage of organs and the complications of matching organ donors to receivers. Though thousands of people could potentially benefit from this procedure, particularly those who have advanced stage heart failure, very few are able to receive a new heart. Those who do must contend with the risk of rejection from the recipient’s immune system.

Using organs from genetically modified pigs potentially paves the way for these lifesaving procedures to become more widely available—not only for those needing a heart but for those who need other organs. In the U.S. alone, over 106,000 individuals are on the national transplant waiting list.

But many people around the world remain uncomfortable with the idea. People’s reactions to the news of Bennett’s new pig heart reflect a mix of surprise, fascination, and amusement. The patient himself was quoted in The New York Times asking, “Well, will I oink?”

This ambivalence is consistent with research on popular attitudes toward cross-species organ transplantation, or “xenotransplantation.” In a 1990s Swedish study, for instance, 77 percent of respondents preferred organs from living human donors, 69 percent preferred deceased human donors, 63 percent preferred artificial organs—and only 40 percent preferred organs from nonhuman animals. While these attitudes are changing, many around the world remain skeptical of or morally opposed to organ transplantation more generally—and especially to animal-to-human transplantation.

Why?

Anthropologists and sociologists who study the ethical dilemmas surrounding experimental medical procedures can help shed light on why the idea of xenotransplantation remains fraught for so many.

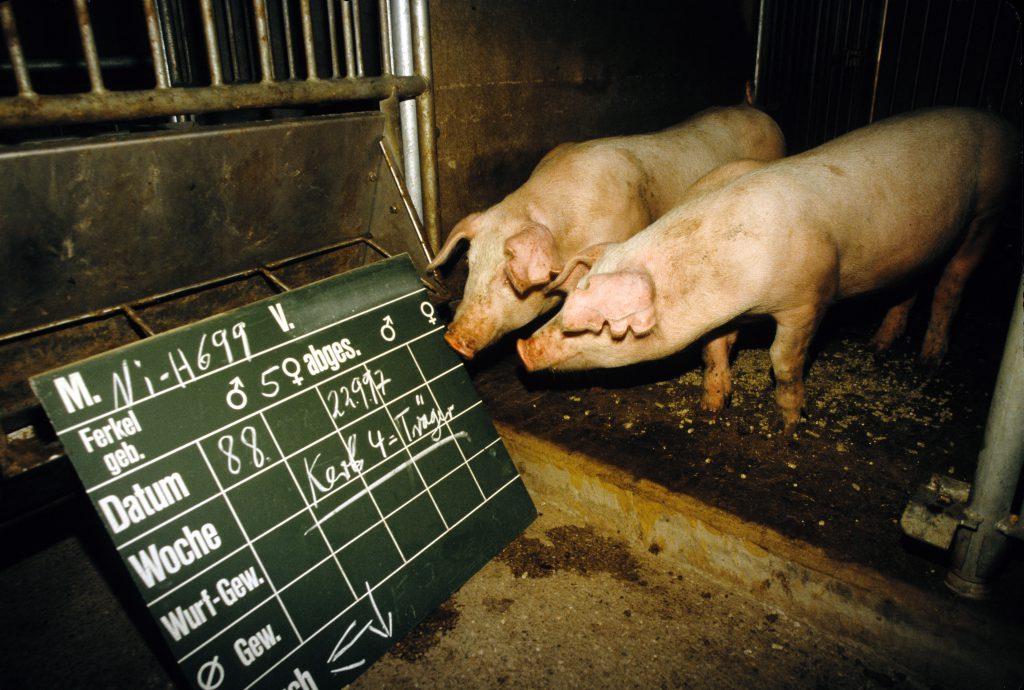

For instance, researchers connect people’s feelings of “disgust” over the idea of receiving animal organs as extensions of widely held cultural ideas about certain animals—that is, seeing some species, such as pigs, as unclean and unfit to belong to the same spaces that humans inhabit. In Islamic and Jewish contexts, in particular, pigs are not only considered unclean but forbidden as food. Given these taboos, some observers speculate: “It’s highly unlikely that the wider Muslim community will eagerly accept the use of pig organs for human transplant, even if someone’s life is at stake.” Other religious scholars and authorities argue such procedures are justified if it means saving a human life.

Alongside more recent concerns over the ethical treatment of animals, these sentiments comprise what sociologist of medicine Gill Haddow describes as an “overall aversion for xenotransplantation.”

Further complicating the “moral thinking” about organ transplantation—whether the organs come from humans or nonhumans—is the fact that some people understand and experience organs in unexpected ways. For instance, while a biomedical perspective sees organs as bereft of emotions, memories, and personality, ethnographic accounts of organ transplantation show that many people feel otherwise. According to anthropologist Lesley Sharp, organ recipients “often express the sentiment that one can acquire the donor’s emotional, moral, or physical characteristics” by receiving their organs.

Having a heart transplant—as compared to other organs—may be especially contentious for Western conceptions of the body, where the heart has traditionally been seen as the seat of the soul and personhood. (In contrast, in some Asian societies, such as the Philippines, the liver was traditionally held in a similar position.) The idea that part of a person persists in their organs after death has taken hold of the popular imagination, as seen in the popularity of books such as A Change of Heart, a memoir about a woman who recounts her personality changing after receiving a heart and lung transplant from a young man who died in a motorcycle crash.

Given these complex and diverse understandings, it’s no wonder that some people have misgivings about what a pig heart might do to a human body.

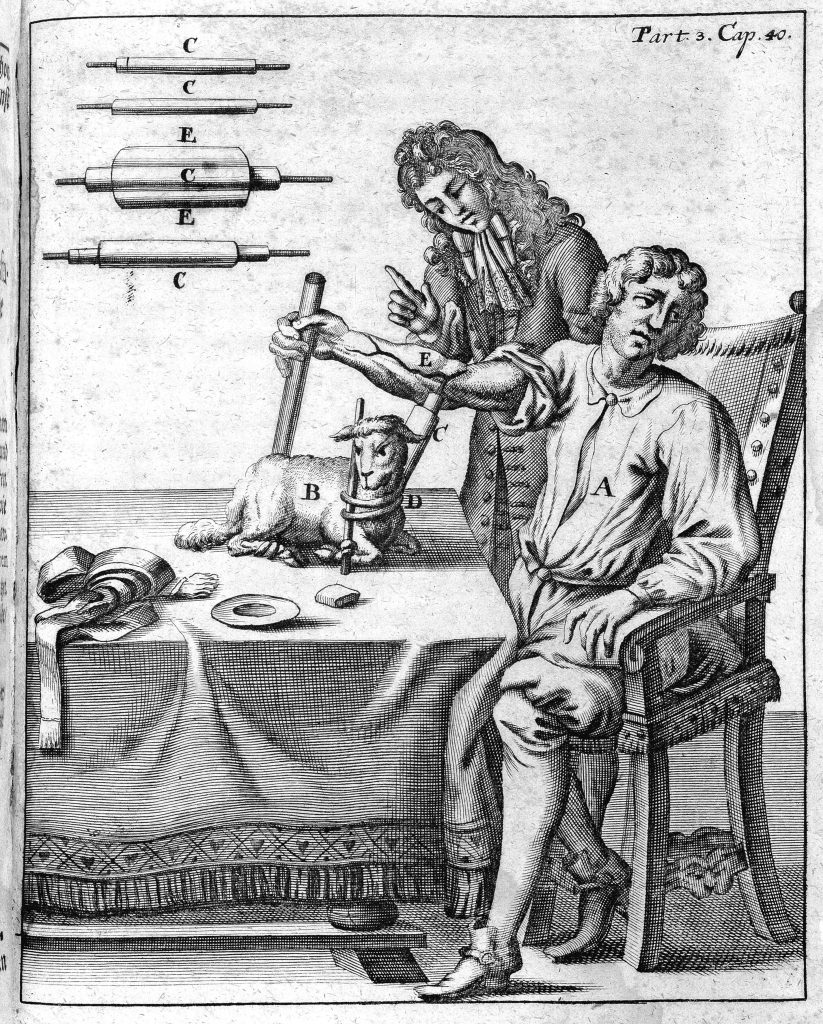

These anxieties notwithstanding, humans have in fact long experimented with using the skin, blood, and organs from other animals—from primates to dogs and cats—to replace their own body parts. David K.C. Cooper, a medical surgeon specializing in xenotransplantation, notes that chimeras exist in stories and religious texts from around the world. These chimeras, according to Cooper, speak to the fact that “humans have been interested in the possibility of merging physical features from various animal species for hundreds of years.”

Cooper explains that since the advent of modern medicine, pigs have been viewed as holding potential for organ transplantation in humans for a number of reasons: their potentially unlimited availability, their rapid growth, and the adequate size of their organs. As early as 1838, the cornea from a pig was transplanted to a human. In 1907, the Nobel Prize winner Alexis Carrel made special mention of pigs in his vision of the future of transplantation: “The ideal method would be to transplant in man organs of animals easy to secure and operate on, such as hogs, for instance.”

Since then, medical scientists have made incremental advances in xenotransplantation. In the 1960s, pig heart valves were grafted to human hearts to make a bioprosthetic heart valve that’s now widely used. However, the breakthrough that would take Carrel’s vision even closer to reality was thanks to genetic engineering.

For the first successful pig-to-human heart transplantation, scientists added six human genes to the donor pig and made other genetic adjustments to engineer a heart that was more acceptable to the recipient’s immune system. This principle had already been tested when the first pig kidney was successfully transplanted to a brain-dead human recipient last year (and then replicated again weeks after the pig heart transplant).

These developments may signal—and contribute to—changing attitudes toward xenotransplantation.

Technological advances in the past, alongside other transformations, have led to similar shifts; in Denmark, for instance, scholars have documented a dramatic shift from opposition to acceptance of organ transplantation in a span of three decades. As Sharp notes, proponents of xenotransplantation have encouraged its public acceptance by highlighting interspecies relationality—or what she calls a “grammar of kinship”—in the way they talk about pigs and other animals.

On the other hand, changing attitudes toward animal welfare have led to concerns over the manipulation and exploitation of animals—including genetic engineering other species for the sake of human health. PETA, an animal rights group, for instance, released a statement condemning the pig heart transplant as “unethical, dangerous, and a tremendous waste of resources.” These critiques serve as a reminder that societal attitudes help determine if—and when—a certain biotechnology gets adopted.

Regardless of the fate of xenotransplantation in the long run, the very possibility of such procedures shows that humans and other animals are more similar than we might think.