Why Shoes Do Not Make the Runner

On September 24, 2023, the Ethiopian runner Tigst Assefa won the Berlin Marathon. She set a women’s world record with a staggering time of 2 hours, 11 minutes, 53 seconds, lowering the previous record of 2:14:04 by over two minutes. A few weeks later, Kelvin Kiptum from Kenya broke the men’s world record in the distance, winning the Chicago Marathon in 2:00:35.

In both cases, the athletes debuted the newest iterations of “super shoes.” Assefa wore the Adidas Adizero Adios Pro Evo 1, which retail for around US$540 and are meant to be worn for a single race. Kiptum sported the Nike Alphafly 3, which weren’t available to consumers until this January.

Conversations about the shoes flooded the running world. One Guardian journalist wrote: “They say shoes maketh the man. But did a pair of trainers make Ethiopia’s Tigst Assefa a record-breaking runner?”

Throughout the 2023 marathon season, broadcasters and commentators have focused on how the athletes’ footwear has helped usher in new world records. But what often gets sidelined is the extensive training and hard-won skills of the elite runners themselves.

As an anthropologist who researches the lives of Ethiopian distance runners, I’ve witnessed what a big shift the super shoe era has been for athletes in East Africa starting in 2017. Most runners from Ethiopia come from poor families in the countryside and have trouble accessing durable running shoes early in their running pursuits. In interviews, athletes who had—or were on the cusp of getting—professional contracts often talked about shoes, detailing the advantages of certain brands and models. Many told me that newer models not only made their racing better but allowed them to recover more quickly from workouts and reduce injury risk.

But in other ways, the super shoe era has exacerbated existing inequalities in the world of running. The mostly Ethiopian and Kenyan runners leading the charge in marathon running today bring commercial value to athleticwear companies like Adidas and Nike by running the world’s fastest times. Their impressive performances are what make the masses vie for these extraordinarily expensive pieces of footwear. But the intense labor they put into training often gets erased, explained away through racist stereotypes about East African runners’ “natural” athletic abilities.

What has led to this situation? To start to understand, let’s look back to another trend: the minimalist running boom.

THE RISE—AND FALL—OF MINIMALIST RUNNING

In 2015, I traveled from the U.S. to Ethiopia to begin my research on women runners. For almost a year I’d been dealing with an incredibly stubborn bout of plantar fasciitis. This exceedingly frustrating injury sometimes presents itself as a dull but manageable ache along the arch of one’s foot. In other cases, like mine, the first steps in the morning felt like a knife was puncturing my heel bone.

Desperate for anything that could help, I decided to go out onto a grass field. I began jogging in circles, barefoot.

Several runners came out and asked what I was doing. They knew I was injured because I had not been attending training sessions.

“What are you doing!?” they asked, obviously concerned. “No shoes? Why!? It’s dangerous!”

I felt foolish.

Most runners I met around this time in Ethiopia were trying to get better, more-cushioned footwear. However, the shoe market in the U.S. indicated Ethiopians were “naturally” good at running because they sometimes ran barefoot.

With super shoe debates taking the running world by storm since 2016, it can be easy to forget just how recently minimalist running was all the rage. In 2009, journalist Christopher McDougall’s book Born to Run came out and sat on The New York Times bestseller list for four years. The book recounts McDougall’s adventure to “find” members of the Tarahumara tribe, who call themselves the Rarámuri, in Mexico’s Copper Canyons.

Falling into tired tropes about the “noble savage,” McDougall depicted Tarahumara communities as free of crime, war, theft, corruption, and obesity. “They didn’t get diabetes, or depressed, or even old,” he wrote, among other passages that depicted these runners as impervious to pain. As part of their practice, the Rarámuri run long distances at impressive speeds—usually without specialized running shoes. By cherry-picking available data and leaning on stereotypes, McDougall concluded the shoe industry was profiting from people’s injuries. He suggested people might be better off just ditching shoes all together.

After McDougall’s book came out, shoe companies began marketing new shoes with low stack heights, or minimal cushioning in the space between the heel and insole, claiming that they mimicked the benefits of barefoot running. And it worked: The minimalist shoe market boomed. In 2006, the Italian footwear company Vibram introduced FiveFingers to the U.S.—a style many may remember as “the weird toe shoes.” In 2009, sales skyrocketed for Vibram and other companies selling shoes with low stack heights.

The minimalist shoe craze also built upon existing assumptions that runners from East Africa, who had been dominating globally in distance running since the 1960s, were somehow biologically destined for success. Some journalists and researchers drew on racist assumptions that because so many African runners grew up at high altitudes, or began their running careers while running barefoot, their bodies were hardened and capable of withstanding more pain and trauma compared to Europeans. Most of these claims were not factual but based on colonial pseudoscience that made false claims about Africans’ superior strength, which, according to these theories, was linked to a lack of advanced intellect.

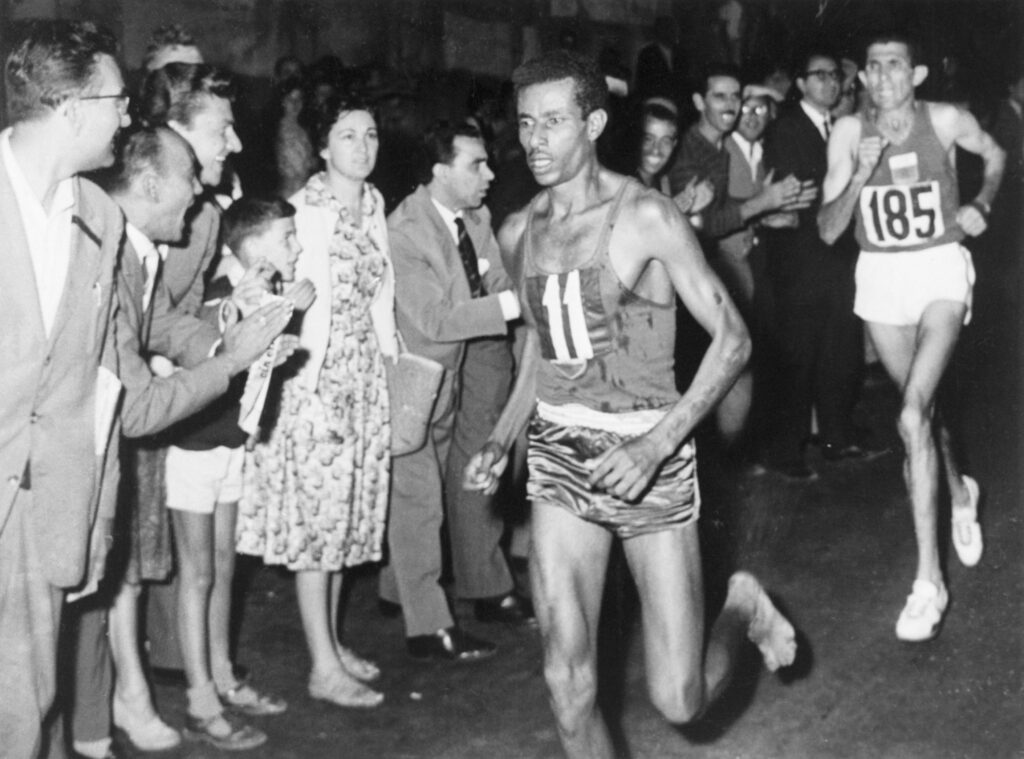

Taking advantage of these stereotypes, Vibram named one of the FiveFingers model the “Bikila” after Ethiopian marathoner Abebe Bikila, who became the first Black African Olympic gold medalist in Rome in 1960 after running the marathon without shoes. [1] [1] Vibram allegedly did not ask the Bikila family for permission to name their barefoot mockup in the legend’s likeness; the Bikila family sued Vibram for US$15 million in 2015, though their case was dismissed by a judge.

But just a few years after sales grew, many who had adopted the barefoot shoes were complaining of serious injuries. A class-action suit was filed against Vibram for making claims, without any scientific evidence, that their shoes would “reduce foot injuries and strengthen foot muscles.” While Vibram denied wrongdoing, they settled to avoid continuing legal fees. Class members were able to submit claims for up to two pairs of shoes, and the company agreed to discontinue false claims that its footwear helped prevent injuries.

But even though the minimalist shoe craze has died down, these racist ideas underlying it continue—in new form.

THE EMERGENCE OF SUPER SHOES

In 2016, Nike began the Breaking2 project. Their goal: to set up an ideal race for a man to break the barrier of running a marathon in under two hours. (At the time, Dennis Kimetto of Kenya held the world record of 2:02:57.) Three accomplished African runners—Kenya’s Eliud Kipchoge, Eritrea’s Zersenay Tadese, and Ethiopia’s Lelisa Desisa—were selected for the project. They were chosen for their remarkable “running economy,” a multifaceted sports science concept that measures, loosely speaking, running efficiency.

In 2017, Nike hosted the first attempt in Italy. The race organizers surrounded the three runners with 30 pacers to help block the wind. A Tesla drove alongside to set the pace. The race start was timed to ideal weather conditions. And as a final move to set the runners up for success, Nike gave them each a newly designed pair of shoes: the Nike Vaporflys—later said to increase running economy up to 4 percent.

These shoes were the opposite of minimalist shoes; they had a carbon fiber plate wedged between a huge stack of specialized ZoomX foam, and they propelled runners in futuristic, somewhat unnatural ways. Some argued that this was unfair, calling it “technodoping” or “shoe doping.”

People noticed more marathon winners wearing Nike shoes. Social media accounts often posted images showing podium finishers—mostly African runners—by their shoes, rather than their likenesses.

Similar to the conversations around barefoot running just a few years prior, advertisers and sports commentators implied it was the shoes, rather than the runners, doing the work.

Meanwhile, the athletes’ training efforts, such as waking at 4:00 a.m. three times per week to run 20 miles, were mostly forgotten. The institutional organizations that support African athletes, such as state-sponsored sport clubs and multitiered management groups, were also ignored.

As soon as the US$250 shoes were available to the masses, they flew off the shelves. Running stores ran out of stock, sometimes in less than a week. Often, the shoes would be resold for twice, or even three times, the retail price. Soon after, hundreds could be seen wearing them on the start lines of 5Ks and marathons.

But what did these changes mean for runners in East Africa—most of whom, without sponsorship, could never afford such a luxury?

FETISHIZING THE SHOES

In 2019, I watched Kipchoge break the 2-hour mark in the Vienna City Marathon, video streaming the moment on phones alongside an elite group of Ethiopian runners. In addition to marveling at his amazing performance, many runners I talked to that day shared how stressed they were about not being able to access the newer models of the shoes he wore.

A few weeks later, I heard one coach making frantic calls to a management agency to see if the correct size shoe for an up-and-coming athlete had arrived. They hadn’t. From shipping logistics to unfair contracts, accessing the newest shoes was often a challenge.

The coach turned to me and explained, “Hannah, these shoes are causing a big problem. The athletes, they think without these shoes, they cannot run well. It’s not good for them. It’s not good for their psychology.”

The coach was right: The super shoes have enabled amazing opportunities for already-successful runners, who make exponentially more money than most Ethiopians. A normal shoe contract for a sponsored runner might be an annual cash payment of US$20,000 per year, plus shoes and merchandise. In comparison, the per capita gross national income in the country is just over US$1,000 per year.

But the stakes feel different to up-and-coming East African runners, who often earn around US$50 per month from their clubs. They know that much slower runners in wealthier countries—even amateurs who just run for fitness—can often access newer models of shoes than they can. These disparities make many Ethiopian and Kenya runners feel that much more disadvantaged in the running world.

Until a few years ago, a woman running a marathon in under 2:12 would have been unthinkable. The super shoes certainly helped Assefa achieve that record. But it’s the athletes wearing the shoes who make these paradigm shifts possible—while at the same time creating high profits for the shoe companies.

The athletes laboring in the shoes deserve more attention.