When Calls for Vengeance Go Online

In 2019, Luis Alberto Quiñonez—who everyone called “Sito”—was shot dead in San Francisco when he was 19. A distant relative by marriage, Sito would not have considered me a part of his life. But in death, he has become a part of mine.

Sito’s tragedy has forced me, an anthropologist whose work focuses on gang cultures, to confront the ways the internet has intensified and transformed the dynamics of gang violence in the U.S. and beyond: I believe digital media played as large a role in Sito’s death as the bullets that ultimately took his life.

As is so often the case, Sito’s murder was precipitated by one committed years earlier. In September, 2014, Sito was with a companion, Miguel Alvarez, who scuffled with and ultimately stabbed Rashawn Williams in San Francisco’s Mission District. The three boys were 14 years old. Rashawn’s younger brother Julius, then 12, witnessed the stabbing. The next day, Sito was arrested and subsequently charged as a minor for Rashawn’s murder.

Fortunately for Sito, the public defender found video footage that made it clear he had not killed Rashawn. The charges were dropped, and Sito was released after nearly five months in prison. For reasons that are not entirely clear, the police did not charge Miguel with Rashawn’s murder despite having video evidence.

However, Sito knew his problems weren’t over: Having the charges formally dropped did not exonerate Sito in the eyes of Rashawn’s family. While Sito was imprisoned, the family created an online petition asserting that two people had murdered Rashawn and asked supporters to call the district attorney’s office to urge the “killer in custody” to be charged as an adult. It stated that he “planned and announced the killing and he committed the murder in cold blood.” While the petition didn’t name the killer, Sito was the only person in custody.

The petition’s comments, written by some of the roughly 2,000 signers, seethed with anger. A number agreed that “the killer” had plotted the murder in advance. “This young piece of **** needs to face what he did. He is a disgrace to human nature!!!” read one.

After his release, Sito saw the family’s petition and became afraid to leave his home.

Nearly a year after Sito’s release, Miguel was shot dead. In the days following, someone tagged Sito’s profile in an Instagram post about Miguel’s memorial. Every time one of Rashawn’s friends “liked” the post, Sito was notified, his aunt told me. Sito was also notified each time someone left a comment. He showed one in particular to his cousin, then to his best friend, and finally to his older brother, seemingly hoping someone would tell him he was overreacting.

It read, “1 down. 1 to go.”

If digital media did not exist, Sito might still have been targeted. But I believe the online petition spread an erroneous account of the murder much faster and more widely than rumors whispered in school corridors could ever have. And the Instagram post only fueled those flames.

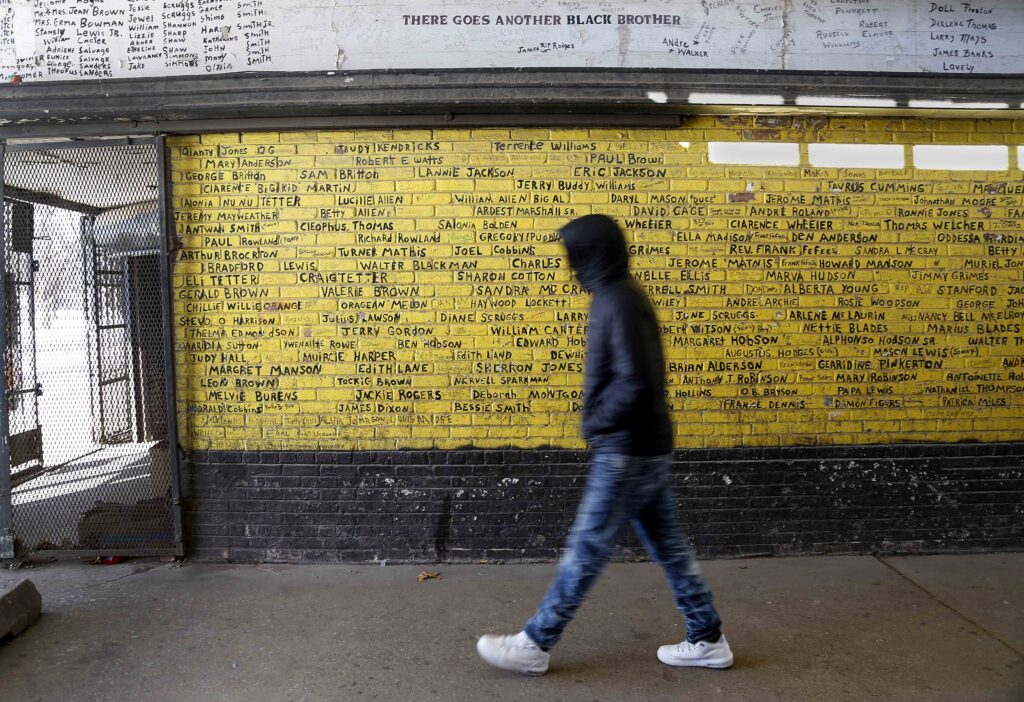

THE RISE OF “INTERNET BANGING”

“Internet banging” is the term sociologist Desmond Upton Patton and his co-authors use to describe the phenomenon of gang-involved youths using social media to celebrate someone’s murder, for example, or to incite violence or intimidate (also known as “cyber banging”). It derives from “gang banging,” street violence typically linked to feuding between rival gangs. As a scholar who also studies gang violence, systemic racism, and police violence in U.S. cities, I’ve been forced to reckon with this term and how accurately it describes Sito’s lived reality.

The term recognizes that gang dynamics, like so much else, also play out in a digital realm, where rumors, gossip, and media coverage intertwine. Increasingly, police investigators also look to digital media for evidence of gang-related crimes. Online media coverage can create and spread images of young criminal suspects long before judges or juries—or defense lawyers—get anywhere near their cases.

In an era where information—true or not—spreads rapidly online, Sito’s case shows how stories circulating on social platforms can criminalize individuals before any formal charge is made—if it ever is. “Innocent until proven guilty” can seem meaningless once “convicted” on Instagram.

Patton and other researchers conducted extensive research in Chicago, where active and chronic gang activity is embedded in communities. In one study, Patton and his team focused on a two-week period in 2015 in which two well-known gang members in Chicago were murdered. The study explored how this real-world violence got amplified through social media aggression on what was then Twitter (now X) in posts aimed at enhancing the reputation of the person making the threats.

“Innocent until proven guilty” can seem meaningless once “convicted” on Instagram.

According to sociologist Randall Collins, an “atrocities loop” begins with insults or trash talk, and gains momentum as stories about the perceived enemy and their villainous deeds circulate. In response, more and more people become offended by the enemy’s actions and a passion for vengeance builds. Sympathy for the victim motivates the aggrieved to create a moral boundary separating good from evil, which energizes someone to avenge the wrongdoing (real or perceived) at the heart of the story. The loop closes when a second atrocity is born from the first. Or, as Collins writes, “Most violence is thus easily perceived as an atrocity, to be avenged by further violence.”

Atrocities often emerge from isolated snapshots, from singular images frozen in time and stripped of context. Social media can magnify and multiply those images.

On September 8, 2019, Sito was murdered by Rashawn’s little brother, Julius. The assistant district attorney who prosecuted the case argued Julius believed Sito was responsible for his older brother’s death and sought vengeance until, ultimately, he became a murderer himself.

COUNTERING MIS- AND DISINFORMATION ONLINE

Reliable data on the relationship between social media and violent crime is difficult to ascertain. But evidence collected by social scientists over the past decade suggests that social media can inflame gang-related violence, making it more visible to more people.

“Rather than use violence to control drug corners,” writes sociologist Forrest Stuart in Ballad of the Bullet, “today’s gang-associated youth use online displays of violence to attract views, clicks, and online attention.”

Stuart adds, “A well-crafted online reputation can spell the difference between going hungry and securing a hot meal, between homelessness and a warm bed, and between abandonment and care. Yet, these benefits come with steep costs that include prison time and elevated risk of victimization.”

In my research, I’ve found at least two promising strategies that both public institutions and social media platforms can and should implement to reduce misinformation and disinformation about criminal suspects. These are media literacy programs and the use of artificial intelligence tools, which, when used responsibly and carefully, have shown potential to detect and flag fake news. Such programs can serve as a valuable resource for educating young people about how to verify information before sharing, and about the toxic threat of rumors and unsubstantiated allegations that go viral. (Unfortunately, one of the largest tech companies in the world, Meta, recently moved away from previous commitments to reduce misinformation and disinformation through fact-checking.)

While these tools aren’t perfect—and they don’t address the larger systemic inequalities that create the conditions for youth gang activity—they may help de-escalate conflicts that can lead to physical violence. In addition, when someone like Sito is exonerated for a crime, official sources—police leadership and district attorneys—need to acknowledge and amplify this news publicly.

Some scholars are looking to push these tools even further. Patton is developing an AI-powered platform in conjunction with social workers, data scientists, young people, and designers. He’s the founder and director of SAFELab, a research initiative housed at the University of Pennsylvania to study how violence impacts young people of color on and offline. Among the programs Patton has designed is JoyNet, which he describes as “an online space for Black youth that centers well-being, helping, and joy.”

Social media platforms are already collaborating with law enforcement agencies to verify crime-related information. It’s essential for platforms and law enforcement to provide the public with accurate information. At the same time, these platforms need to stay aware of the risks that artificial intelligence can pose, particularly when it comes to overpolicing young people of color who may be dealing with mental health challenges or trauma.

We cannot allow social media to infringe upon and render meaningless the presumption of innocence. If we do, misinformation, catalyzed by internet banging, will spin more cycles of violence like the one that I believe claimed Sito’s life—years after he was found innocent.