Phantom Vibrations of a Lost Smartphone

David, an American cyborg, has lived in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, for the past month. [1] [1] All names have been changed to protect people’s identities. As a cyborg—a human-machine hybrid—he can work from anywhere as long as his body remains reliably connected to the internet.

Prior to traveling to Brazil, local friends warned him about techno-bandits who roam the streets of Rio, stealing pocket-sized cybernetic prosthetics from unsuspecting tourists to sell on the black market. So, when he first arrived in the city, David exercised extreme caution. He moved through the streets with vigilant eyes and a guarded stance, keeping his prosthetic concealed most of the time.

But tonight is different. After a month in Rio, David’s grown accustomed to the city’s hustle and bustle. The initial apprehension that once gripped him has faded into the background, replaced by bold confidence—and a touch of cockiness.

As he walks down the sidewalk, a familiar vibration pulsates through his prosthetic. David unsheathes it and momentarily dissociates, shifting his attention from his physical environment into a virtual world. The alert signals a message from a colleague—nothing urgent.

After a moment, David refocuses on his surroundings and locks eyes with two men sitting on the ground. They stand and approach him, speaking rapidly in Portuguese, making frantic gestures to disorient him. Before he can react, one grabs the collar of David’s shirt.

The bandit pushes David against a wall and holds a knife up to his abdomen, while his accomplice yanks the prosthetic from David’s hand. As suddenly as they appeared, the techno-bandits turn around and vanish into the night.

Though physically unharmed, David’s deeply shaken. Stunned and startled, he staggers back to his apartment.

In the days that follow, he’s gripped by unsettling feelings. David senses vibrations that aren’t there. He imagines the weight of his prosthetic against his body. He instinctively reaches for it when he wants to access or remember information, only to grasp at empty space. At one point, he even experiences an auditory hallucination, hearing sounds emanating from the vanished device.

It’s not the theft that haunts David; it’s the acute absence of his prosthetic. This cyborg is experiencing a phantom limb–like phenomenon.

BECOMING CYBORGS

When you imagine a cyborg, what sort of creature comes to mind?

For many, a cyborg represents a futuristic entity, a product of technological developments yet to come. However, the anecdote above comes from dissertation fieldwork I conducted in 2022, exploring human-computer interactions among gay men based in California. More specifically, this research focused on understanding how these users’ relationships with smartphones—and the tech companies that create these devices and their wide-ranging applications—are transforming fundamental features of human existence, experience, and performance.

To learn more, listen to an interview with the author on the SAPIENS podcast: “Smartphones Are Bicycles for Our Minds.”

It’s a widely acknowledged but often underappreciated fact that in less than two decades, smartphones have revolutionized most aspects of everyday human life. These small computers have radically changed the ways people in many parts of the world communicate and transmit information; learn, teach, imagine, work, and play; trust, empathize, and express other emotions; produce, distribute, exchange, and consume; move, navigate, and migrate; and even eat, sleep, copulate, and defecate, among other things.

But David’s account of being mugged and experiencing phantom sensations suggests smartphones have changed more than just how we do things. For many users, our interactions with these devices have profoundly reshaped what it means to have and be a human body.

PHANTOM SENSATIONS AND THE BODY

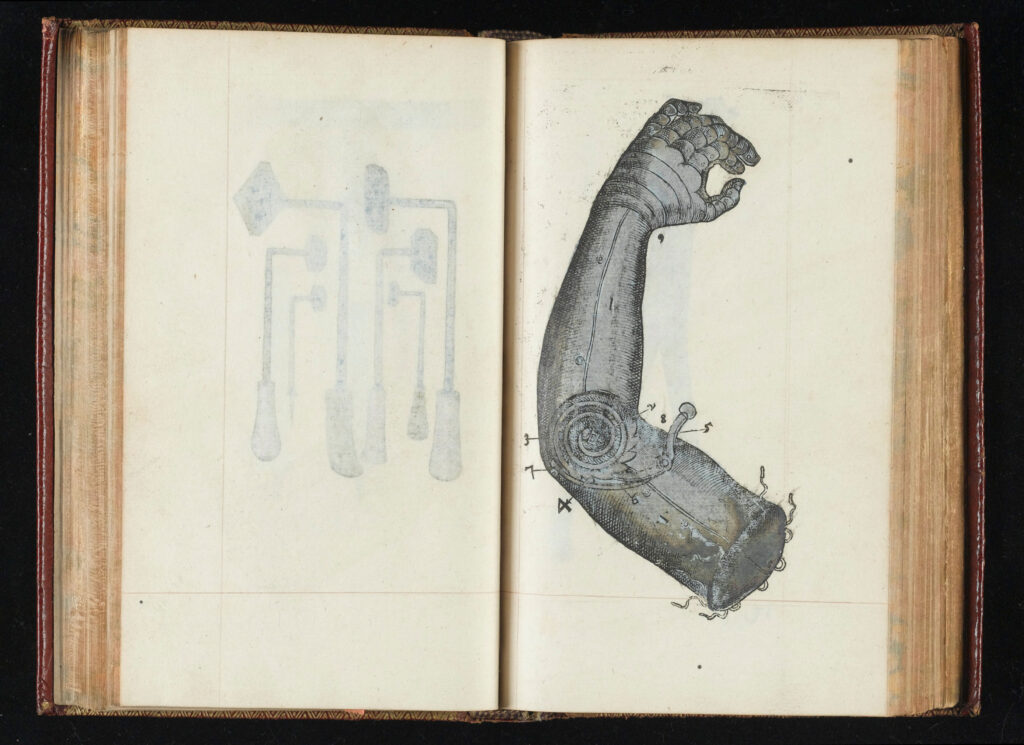

Phantom sensations, like those David experienced after the loss of his smartphone, refer to a phenomenon in which an individual experiences sensations involving a body part that is no longer physically present. This phenomenon has been recognized by various cultures throughout history, but French barber-surgeon Ambroise Paré was the first to document it in the context of Western medicine. In his 1564 Treatise on Surgery, Paré describes cases in which wounded soldiers complained of pain in recently amputated limbs.

A wide variety of experiences fall under the umbrella term of phantom sensations. These include pain, tingling, itching, and experiences of performing a task with a lost body part, such as trying to pick up an object with a recently amputated arm. While often associated with limbs, phantom sensations can involve other body parts as well. For example, some individuals report phantom erections after penile amputation or sensations of passing gas after the surgical removal of the rectum.

Although phantom sensations have been documented for centuries, the underlying physiological mechanisms are not yet fully understood. However, scientists believe they’re connected to neuroplasticity—the nervous system’s ability to change, adapt, and reorganize itself in response to learning, experiences, or changes to the body.

Our nervous systems maintain body schemas, comprehensive mental models of our physical form. These schemas—shaped through continual sensory inputs, motor experiences, and environmental feedback—enable the brain to create a dynamic, internal map of the body’s structure and its potential for interacting with the world. After the loss of a body part, the nervous system must adjust this mental model to reflect the body’s altered form.

But this process of recalibration is complex and can take a while, requiring our nervous system to unlearn deeply ingrained patterns established over years. During this period, individuals may experience phantom sensations involving that missing body part until the brain’s model reconfigures to its new spatial reality.

SMARTPHONES AS PROSTHETICS

At first glance, describing a smartphone as a prosthetic might seem like exaggerated phrasing. Smartphone users don’t typically think of their devices as artificial body parts. But reports of phantom sensations by David and other research participants suggest our brains have come to represent smartphones as enduring extensions of our physical bodies, not unlike how a person with limited vision might incorporate a cane as an extension of their spatial and perceptual system.

Through regular, reliable, and repetitive use, smartphones modify the brain’s structure, forging new neural pathways and rewiring neural networks. Just as the nervous system integrates each limb into its mental representation of the body’s form and possible functions, it can also incorporate smartphones into this body schema. In other words, humans can experience phantom sensations when disconnected from our smartphones because our nervous systems perceive them as integral parts of our bodies.

Experiences of smartphone-related phantom sensations point to a broader biological capacity shared across species: the ability to flexibly modify one’s functional morphology through tool use. In some cases, an organism will profoundly integrate this tool into their body at spatial, cognitive, and perceptual dimensions—a process called tool embodiment.

Tool embodiment is neither new nor unique to smartphones—or even to humans. Yet smartphones transform our bodies in unprecedented ways by continuously connecting them to the internet, which functions as an external digital nervous system. This connection augments users’ ability to transmit, perceive, process, and respond to information beyond the limits of our innate biological bodies.

This has important implications for users’ privacy and autonomy. For example, seamless integration with internet-enabled smartphones subjects users to continual, real-time feedback loops orchestrated by external actors. While not inherently negative, many tech companies abuse this capability, using sophisticated algorithms to subtly modify our behaviors and worldviews in ways that prioritize their corporate interests, often outside users’ conscious awareness.

REGAINING AUTONOMY

A few days after the mugging, David returns to the United States. Upon arriving in Los Angeles, his immediate objective is to buy a new phone. After dropping off his bags, he rushes to the store. This urgency isn’t just about replacing a lost gadget; it’s about restoring a critical part of himself, something that became an extension of his body and mind through years of habitual use.

Smartphones have transformed what it means to be human by turning computing from a discrete activity into a way of life for many users. David’s phantom sensations while separated from his smartphone illustrate how deeply integrated these devices have become.

While many readers—and devoted smartphone users—may find this influence troubling, abandoning our devices isn’t the solution. Our smartphones provide essential access to information, communication, and services, making them indispensable for many aspects of everyday life today. Instead, consumers should demand that tech companies prioritize human-centered designs that empower us and preserve autonomy, privacy, and identity, rather than undermining them.

As we move forward in this era of pervasive connectivity, we must think more deeply about how these devices have become enduring extensions of our bodies and minds. The boundary between body and machine has never been blurrier; understanding this dynamic is key to ensuring that future technological designs will enhance, rather than erode, our humanity.