This special SAPIENS podcast season, co-hosted by Doris Tulifau and Kate Ellis, tells the story of famed anthropologist Margaret Mead’s epic life and controversial research in American Samoa to explore key quandaries about the human experience: sex and adolescence, nature versus nurture, and the question of whether it’s ever possible to fully understand cultures different from your own. In addition, we hear from Samoans themselves about their views on Mead’s legacy and their lives today.

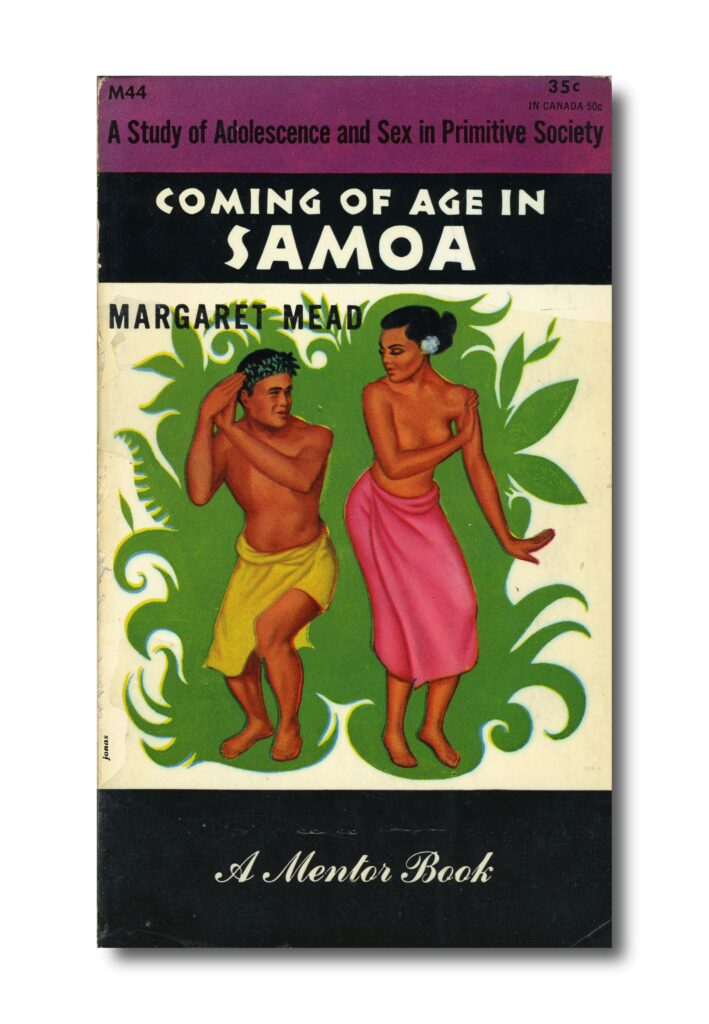

In 1928, when she was just 27 years old, Mead published Coming of Age in Samoa: A Psychological Study of Primitive Youth for Western Civilization, which investigated the sexual lives of young women on the Pacific Islands. The book was an instant bestseller, challenging people in the U.S. to rethink much of what they had assumed to be true about sex, human biology, and growing up. Mead became one of the most influential anthropologists in history and one of TIME magazine’s most powerful 25 women of the 20th century. She received a U.S. presidential medal of freedom, and a U.S. postal stamp was made with her picture on it.

But what if Mead’s findings about Samoans were wrong?

Five years after Mead’s death, anthropologist Derek Freeman rebutted the central claims Mead made in her career-launching work, sparking a media sensation and challenging the field of anthropology. The controversy that followed sparked questions about the science of intercultural understanding and why Samoans weren’t empowered to speak for themselves.

SAPIENS is an editorially independent podcast funded by the Wenner-Gren Foundation and is part of the American Anthropological Association Podcast Library.

Season 6 of the SAPIENS podcast was made possible by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Part of the production team traveled to Pago Pago, American Samoa, to begin field recordings for the podcast.

Chip Colwell

Rithu Jagannath interviewed Sia Figiel.

Chip Colwell

The Atauloma Girls School, which Margaret Mead visited in 1925, today is in ruins, consumed by the forest.

Chip Colwell

The production team visited the school where Derek Freeman taught in Apia, Samoa.

Chip Colwell

The production team recorded the ocean sounds near Vaitogi, American Samoa, where Margaret Mead lived in 1925.

Chip Colwell

Season co-host Doris Tulifau (seated right) and producer Sia Figiel (seated left) discussed their work on a television program produced in American Samoa.

Chip Colwell

Ari Daniel interviewed Andra Samoa, a former member of the American Samoa House of Representatives and descendant of Andrew Napoleon, who worked closely with Margaret Mead.

Chip Colwell

The production team interviewed Afalupetua Utai, a church pastor at CCCAS Vatia.

Rob Matau (left) and singer Malo Faamausili (right) recorded much of the music for the podcast.

Tanya Volantras

On the final day of recording, the production team attended a Sunday church service at CCCAS Petesa Tai.

Chip Colwell

Trailer: The Problems With Coming of Age

[introductory music]

Peta Si’ulepa: We need to tell our own stories. We need to articulate our reality from our own experience.

Bradd Shore: It was the single biggest media storm in the history of anthropology.

Doris Tulifau: In 1925, a 23-year-old anthropologist named Margaret Mead set sail for American Samoa in the South Pacific to study whether being an adolescent always has to be so hard.

Charles King: She wanted to be a public intellectual. She wanted to be taking on the big issues of her day.

Kate Ellis: Mead wrote about what she found in her first book, Coming of Age in Samoa, and it rocketed her to fame. She depicted a place where girls were free to explore their sexuality and challenged Americans to rethink adolescence, parenting, and big questions like nature versus nurture.

Charles: Suddenly, you dethrone your own culture, and make it just one of many ways of making sense of the world.

Doris: Decades later, controversy erupted. Anthropologist Derek Freeman said Mead had been hoaxed—and that her findings about Samoa and her insights into what it was to be human were wrong.

[people singing]

Peter Hempenstall: What he disagreed vehemently with was her sense that Samoa was this beguiling romantic paradise.

Mary Catherine Bateson: Freeman rode her fame by attacking her.

Kate: The debate captivated the public.

Paul Shankman: She had gone from public icon to cultural roadkill in just a matter of months.

Nancy Lutkehaus: The American public’s interest wasn’t so much in Samoan society and what either of them had to say about Samoan society. The Samoans got kind of lost in that discussion.

Doris: For Samoans themselves, Mead’s work has cast a long shadow.

Peta: I was affronted by the use of the word “primitive.”

Sia Figiel: And I just remember asking who’s Mead? Who’s Freeman? We didn’t know. And yet these narratives were supposed to be about us.

Tisa Faamuli: I have a problem with foreigners telling our story. They’re not telling it from our eyes and our heart. Nobody ever interviews us and asks us our opinion of ourselves, our history, who we are.

Doris: In the newest season of SAPIENS “The Problems With Coming of Age,” we do just that. I’m Doris Tulifau.

Kate: And I’m Kate Ellis. Join us as we investigate the epic life and controversial research of one of the 20th-century’s most influential scientists—and the complicated legacy she left behind.

Coming this October, wherever you get your podcasts.

BONUS

Join the conversation around season six of the SAPIENS podcast, “The Problems with Coming of Age,” which explores the famed anthropologist’s controversial research in American Samoa and what it reveals the biggest questions about growing up and being human. In this live panel discussion, podcast co-host Kate Ellis, podcast senior producer Tanya Volentras, and Kiana Fuega and Ronalei Gasetoto, students at the University of Washington, discuss Margaret Mead’s tangled legacies and the needed voices of Samoans.

>> KATE:

We will give the first five minutes to let people trickle in or at least wait until the trickle slows.

>> KIANA: My blessing to everyone who is coming into this room. I will not sing for you, because I’m very well aware of the not-gifts that I have been given. I don’t know, Tanya, yes, I am. Beautiful. Sounds like you met Rona already. Just briefly.

Is your family from independent Samoa?

>> TANYA: Yeah, yeah, yeah, I was born in San Juan, yeah, in the hospital. Yeah. But I lived — I can say that.

>> KIANA: Yeah, you said you are in Norway?

>> TANYA: Yeah.

>> KIANA: All right, we will go ahead and get started. Welcome, everyone, to our discuss today. My name is Kiana Fuega, and I have my cohorts here from the University of Washington. I will let her introduce herself too before we allow space for our panelists to introduce themselves and welcome you into this conversation on the legacy of Margaret Mead.

It’s been hosted in a season for the SAPIENS podcast. So I will give you the floor to Rona and we will pass it around for introductions.

>> RONALEI: Hello, everyone, welcome. My name is Ronalei Gasetoto. I’m also here at the University of Washington as a grad student in the Ph.D. program for sociocultural anthropology as well as pursuing a master’s of education in culturally sustaining education.

Yeah, we can get started with our panelists. I will hand it off to Tanya.

>> TANYA: My name is Tanya Volentras. Tanya Volentras. I was born and raised in San Juan. But currently, well, yeah, okay, skip the story. Yeah. I’m actually doing a Ph.D. with James Cook University in Australia, but my interest, my main research interests are San Juan ways of being especially through music and performance.

But I was honored to asked be a professor for the SAPIENS music podcast ask and it’s been a real learning experience. I have enjoyed it. That’s basically my main role in this project. Kate?

>> KATE: Hi, everybody, I’m Kate Ellis. I was trained as an anthropologist at Columbia University, and but I have moved into radio broadcasting and documentary-making. So I now serve as an editor at a show called The World which is an international, a U.S.-based international news show for domestic audience.

But I was honored to be asked to cohost this project.

>> KIANA: Awesome. I want to thank everyone for joining us today with Kate, Tanya, and Rona. My name is Kiana as I mentioned before. Along with Rona, I’m a doctoral student here at the University of Washington. Sociocultural anthropology and my interests are in pedagogy and looking at how do we preserve the ways of knowing for indigenous communities most especially for where I’m indigenous to which is Samoa currently known as American Samoa by

way of Lenoe. So as Rona, Tanya myself talked about really briefly right before this started, opening up this space, we all had the great opportunity to be in Samoa in this past year. It looks like you were there as well, Kate. Kate was there?

>> KATE: I was not there. I am sad to say.

>> KIANA: Okay, but Samoa is a huge center in this conversation especially as it relates to Margaret Mead. And the body of work that she’s done in building a foundation in ethnography and anthropology. So Rona and I were thinking through some discussion points as we were listening to the podcast.

We were just grappling with the legacy of Margaret Mead as being in anthropology. And so Rona, I will give you the space. I don’t know if you want me to go first or you want to go first. I want us to bounce back and forth.

>> RONALEI: Yeah. Whatever, whatever works. I mean, I guess in addition to Kiana, my family too being from Samoa, and being in anthropology, it’s a lot, right. So I think being able to say that out loud is really important in this space, right.

But I think one of the main topics that we talked about was ethics. And I have a lot of understanding and just anthropology as a whole being that it is founded on colonial extraction, right, from the research, right.

So I think touching on indigenous positionality might be a great start, Kiana.

>> KIANA: Yeah. So one of the — I will say what really resonated me because I heard about this and I saw Doris’s name. If Doris comes in, we are going to let her join this panel and other voices in the podcast, a distant relative of mine. She was interviewed in the podcast as well.

And just folks talking about what Mead’s contribution to anthropology has been. And it’s kind of been this field of knowledge that’s so common to the Western world Mead talking about sex and adolescence in a time where that wasn’t a part of the American mainstream conversations.

And using Samoans to prop up that conversation and saying here are these people. This is what they do. Why are we not this way because they are primity and we are supposedly the more civilized, the more progressive civilization. What are we not doing right?

What has always just bothered me about that, my introduction to Mead was in high school when I was in Samoa in the library like many other Samoans is everything that I learned in reading the work in reading articles about the work is that much of what she frames Samoa as is not a Samoa that I knew was someone who has been going back and forth to Samoa since infancy.

And, you know, for the last few decades, nor was it a Samoa that the community that I was so tightly raised with, they didn’t reflect any of these narratives that she was given and so when I listened to narratives about Margaret Mead being constantly provided platform a hundred years after her work in Samoa or nearly a hundred years after her work in Samoa as a Samoan who has blood ties to her work

as someone who is indigenous to that space, as someone who is in the field of anthropology, I think it’s important for us to really unsettle what is Margaret Mead’s legacy not only as it relates to the people that are written about, as indigenous people, but even in the current day, what does that mean to Samoans in the current day whose supposed cultures are written about and lead to all of the tribute to kind of American society at that time.

But do not get to speak for themselves. And so I think there’s a place where Mead took up a lot of space of Samoa’s narrative in the field of anthropology that was really uncomfortable for me. And I will let Rona and Tanya and Kate speak to their own experiences of how they perceive Mead in her connection to them and their connections to the field.

But I don’t know if that’s so much a question, but I think it’s definitely something that has to be addressed first as we enter into conversation around Mead, because I think there’s so much dialogue where she’s a venerated person in anthropology and in the Western world. But when you come into Samoa, there’s predominantly two main narratives.

You either don’t know who she is or you completely reject or don’t care what she’s written about since there’s this disjuncture that happens, but we don’t get to talk about it.

So I am going to hand it off to y’all. Just, like, how to ground the conversation on where you enter into the conversation.

>> TANYA: Rona?

>> RONALEI: Yeah. Yeah, yeah, yeah. I guess just to add to all that, there’s a lot of discomfort that comes with me and saying that out loud is important. I wasn’t introduced to her until I got to my undergrad years. And I think it’s just something that I read the first page of and I was, like, okay, no, that’s not right.

I am going to rewrite the narrative, right. And I think owning and the ownership that we have as grad students, like, in the discipline is important, right. And I don’t know, all this, the legacy of Mead still lives within us. Like, within this discipline and trying to unlearn that from within the discipline is a very interesting dilemma.

And I say this because it really structures how people view us, right, the confinement of what Mead has told the world about Samoans. And I think a lot of that that I have been still wrestling with, but yeah, Tanya, Kate? Any input?

>> TANYA: Well, when I first read Mead I was about 15 and I thought it was silly. I credit that book for becoming an anthropologist. A little seed was born in me. No, I am going to write a proper narrative Samoan people because I thought it was terribly wrong.

But later because of this podcast project, I revisited her work and read it, like, closely. And the book and The Coming of Age. And I actually don’t find it as bad as I did when I first read it.

Now, okay, put aside, I mean, the question of colonial ideologies and all that, that’s one thing, okay. I’m totally on the same page with you two on that because that’s a whole argument.

But, like, some of her ethnography, like, remember it was in the 1920s. So, you know, I don’t know when you guys read it, but it was more recent and your experience with Samoa and Samoans is different than hers. So I don’t want to defend her completely, but some of the things she described, I did recognize her ethnography, some of her descriptions.

I think personally where I find that she fails is she just didn’t understand Samoans at all. She misrepresented how we are as people. But I still enjoyed the ethnography if you know what I mean, yes, little things like that. I really enjoyed that. So, yeah, I have a very mixed relationship to her.

(Laughter)

>> TANYA: Yeah, so that’s my stance at the moment.

>> KATE: I think the reason I was really interested in this podcast is so that it could give a platform for conversations like this because clearly this voice of these voices were missing nearly a hundred years ago when she first published her book. And I guess one of the questions I have is how do you separate the work from colonialism?

Like, and I don’t know has to answer that, but it’s, like, the question that I think I continue to return to. Anyway, those are just very quick thoughts that I have about it. But mainly I’m just alive to this conversation and only want to hear more, because I think it’s so important.

>> KIANA: Yeah, I think that is an important question or whether even there is a possibility for separating it from colonialism, because part of what gives Mead the platform that the funding, even the power to provide the narrative as the singular narrative is the power of colonialism and being from the Western world.

And I agree with you, Tanya, so when I first read it, this was probably, like, some years ago, and there are parts where I’m, like, yes, I recognize those parts. I think the overarching part when she would talk about chief, the village council and pieces like that, yes, village councils are a part of Samoan society. Yes, part of the structures you are talking about is important to Samoan society.

I think that wasn’t the part that was remembered about it, is all of these kind of nuances of Samoan society, especially as if they are reduced to a primitive society when us as Samoans, no, Samoan society and culture is complex. Even to think about ourselves as a primitive society which is to say that we have not integrated Western civilization is to assume that we have no civilization or we have no, our own ways of knowing that regulate our own societies.

And Samoans entirely that. I think there’s, I think in reading through her work it was less of my rejection of, like, what is adolescence, sexuality look like at that time, because I don’t know. I only know what’s sort of attitudes are passed down to us from my parents who accept the attitudes passed down to them from their parents and before.

And a lot of it isn’t this, like, have fun, have sex, whatever you want, sex. But that’s my own experience and so I’m less about wanting to unsettle that, the Samoa that she was writing about didn’t exist. It’s more so that the Samoa that a woman from Boston who had never been to Samoa before who had spent a limited time in Samoa writes a narrative that is passed around the globe that is accepted into mainstream American culture as a factual verified legitimate narrative of Samoans.

And in my 30-something years of living, it doesn’t match up to the Samoan lived experiences I have or family that I have who are also from Samoa. So that’s the part of anthropology colonialism that is unsettling for me, is that there’s so much space for nonindigenous people to write the narratives about us, and then but they don’t write it towards us.

I remember reading in her editors’ note for the version of Coming of Age that I read she had mentioned the Samoa she had written about is not the Samoa that exists. And I was, like, you know, of everything I know about Samoa, it is a place very slow to change. Yes, it’s changing. But Samoa is also very proud place of passing down what they know to the generation after.

It’s integrated. Those are kind of some of the things that are sitting with me. But I’m just thinking about what might be sitting with either of y’all.

>> TANYA: Can I ask maybe a little bit of a controversial — nah, anyway, a question straightforward to both you and Kiana and Rona. Like, were you brought up very Christian? Are your families very Christian? Yes or no?

>> RONALEI: Yes.

>> KIANA: Yeah.

>> TANYA: Okay so, this is why I find that Samoans especially react against Margaret Mead because it does contravene a lot of the way that Samoans are brought up with a strongly Christian precepts and way of life. And that’s, you know, I think that’s the main — I think that’s the main objection from Samoans, the grounding.

Apart from all the misrepresentation and cultural mistranslations and things like that, I think that is because there is a sort of very strong emphasis on being, you know, like a good girl or, you know, you know, and you don’t just go behind the bushes, whatever and just, yeah.

So I think in my analysis, this is why most Samoans get upset about Margaret Mead. But, for example, I mean, I do know — okay. I will tell you this story. So I know this, the former head of state’s wife, Philia. Her parents were missionaries at the time.

And they said that they agreed with what Margaret Mead wrote. Now, whoa, controversy, controversy, ooh!

(Laughter)

>> TANYA: What I mean is is that my own experience of Samoans is — there is a certain easiness about sex. There is, there is. Not within the framework of Samoan families and not especially not certain generations who have been really raised, like, properly in Christian sort of going to church and stuff like that.

But even myself, I experienced it like it’s like there is a kind of lack of shame around certain thingses. There’s shame on one side and lack of shame on the other side. They have both worlds, actually. They live in both worlds. They really do. We really do I should say. It’s about what’s publicly accepted. I think Penny Sheffield in the latest published episode said it really, really — she framed it like what someone got wrong was to think that the publicly

acceptable way of being was what was inside of the private lives. Like kind of a dual way of living. And I don’t really mean to make it like a this or that dichotomy. It’s just something I have been wrestling with in my own writing. They are very flexible. Samoans are very flexible.

Christianity has a rigidity about it. You are either wrong or you’re right. You are good or you’re bad. They have got this, you sin or you don’t sin, whereas Samoan in real Samoan, like, real Samoa, they have got this flexibility about things. There’s a lot of negotiation. There’s a lot of if someone does something wrong, for example, in the village, then in the old days and a little less to some extent in these days, they will sit together either in the family or in a formal setting with

if it’s something serious. They will talk about T they will say this is wrong, this is right. You have done this. And the person has to, you know, kind of show some sort of remorse. And then they kind of work things through. They find a certain way of compensation, certain way of actions, what the person should do to make everything right.

It’s not like, okay, you have done something wrong. Out. You know what I mean? What I mean is Samoans are much more flexible in their world view than Westerners, that be outsiders. But they live with both. I find they can live with both. They can fulfill the demands of Christianity which I think is a colonial project myself and I’m not anti-Christian. I’m just saying it’s definitely a colonialism of a sort.

But most Samoans would totally disagree with that. A lot of Samoans that I know would be horrified that I say that, you have been colonized by Christianity, you know? But I think that that has definitely affected the Samoan world view, definitely. And yeah and put in, like, a strong left or right, wrong or right structure where in Samoan culture, it’s there’s more negotiable, more flexible, more forgiving, in fact.

The heart comes into these kinds of situations. One’s feelings, one’s relationships, that all counts. You don’t separate your feelings, your family, your background from, say, if you’ve done something wrong, they will take into account all of that. You know, who you are, what you were like, not just that one particular transgression if that’s a case of deciding wrong or right about a person.

Anyway, my two cents.

>> KIANA: I want to give space for Rona or Kate to contribute to that as well, and I see that we have also a question in the Q&A that we’re also already coming up on time. There’s so much. There’s so much for us to unpack because much of what you said. I will stop there. I will hand the space over to the both of you all and you can follow up with this question.

>> KATE: Let me let you go, Rona, let you react to that.

>> RONALEI: Yeah, yeah, yeah. I think there’s a lot to unpack. And I don’t think we have enough time. But I think it just goes back to the ethics of how the research was approached that I feel that it’s continually being perpetuated and still our discipline and thinking, too, I mean, being in America, too, the placement and how Mead is praised, we will say that, through, like, institutions, right, being in exhibits.

I think there’s a lot of connotations that affect how I see myself within the discipline now that a hundred years later, right, I’m in this space. But I’m also like, not because there’s a whole history of what has been said about someone. I know there’s a lot of like her working specific to — I can’t even think of it — being towards adolescence, right.

But I think there’s a lot of things that are — how do I word this? That are just from the Samoan culture that I feel can be given back to, the stories and experiences. And I think thinking, too, of the Samoan community, there’s also different experiences within the communities that people experience that may not be true for all, right.

And I think just working through the ethics of that is really important. And I find it needing to be discussed more about. But I will just leave it right there so I can pass it on to you, Kate.

>> KATE: I think this, to me, raises this larger question of, is it the case that any given culture that there would be these different levels of what we say, you know, these are the values that we say we subscribe to, but this is how we live in community? You know, and those two things might look different. It just, this conversation makes me just have larger questions about, you know, just about any other given culture or community in terms of sometimes I don’t even know if the term

duality even captures it because it’s more than a duality. And I am also Rona, really interested in your question about the ethics of all of this. It seems like there’s a central piece of that in here. And I know we don’t have very much time left. But I think that that’s a really crucial key question in all of this.

It seems like, you know, there are these findings that were published, but beneath that, what are the ethics of the project itself? And anyway, I’m not sure I have a way to tie off that thought. But those are the kinds of questions that are coming up as I listen to you guys.

>> KIANA: I don’t think it has to be tied up, right. I think those are some of the unsettlings that this kind of work provides for us. Because you do bring up a great point, Kate, is that there might be perceptions or experiences that we have individually and then there’s kind of the collective, the social, the norms that are overarching, right.

So there’s a way that we might present ourselves with interests that we have in how we want to operate within society and then there’s a big if for Samoa that kind of shapes how we’re supposed to interact with each other and there’s a way that Samoan girls and Samoan women are supposed to reguard their lineages or representatives of the families and the clans they are from, the villages that they are from.

I think more than Christianity for me it’s much more when I think about how, yes, that different time, right, but how much Samoan women are shaped to be representatives of their families and how, you know, there’s such a limit in what we can and cannot do before it becomes a family issue versus the men from your family.

I think that’s something that has to be spoken towards and Mead’s time is maybe heralded as a feminist icon before women’s rights movements. But I’m, like, what does that mean to Samoan women who would not write about — who may not write about themselves in the same way, who may still have to have layers of unpacking before they offer anything near the conclusion that Mead gave for us?

Like everyone is saying, there’s so much more to unpack and I don’t want to take up too much more time before I offer this question, at least one. We are at time. Time is a Western instruction. I want to at least offer one opportunity for a question. We have one in our Q&A. And it asks, what measures can be taken to either balance or counter the Mead narrative harming the narrative that’s harming the true perspective?

What measures can be taken to either balance or counter the Mead narrative that’s harming the true perspective?

>> TANYA: That’s easy. All of us write more Samoans or whatever it is from, wherever you are from, write and and and discuss and tell and show. I am finding that very difficult, actually, to do, to represent Samoa in a really strange way.

Because it’s like because I’m trying to relate from something that’s felt to something that’s thought into the words on paper. So I’m finding some of that translation process a little bit difficult. But I think that’s just what it is. And it’s happening in specific, more people are writing, writing and sharing their understanding. And it’s been accepted in different places.

Museum is very open to getting, yeah, some more perspectives because they have a lot of Samoans there to help them with. Also disciplines, health, developmental studies, you know. So, yeah, I think that’s the only way really is just to have more voices, yeah. Rona?

>> RONALEI: Okay, I will be brief. But I think in addition to writing, I think there’s just a need to understand as researchers go into different communities that aren’t their own to honor and understand the sacredness — sorry (Background noise).

>> RONALEI: The sacredness of that gap, that gap that those outside the community will never understand and just sitting with that, right. And then those, like, and vice versa. Being able to be in the community and know that you can use language and all these emotions and feelings to express how your reality is. But I think honoring that and understanding that to work with indigenous people, you have to understand that you can say all these things.

But sometimes you will get it wrong, but I think that that’s that radical respect that needs to be reimplemented or not reimplemented, implemented in research. That needs to be discussed more and be okay with that. So… yeah.

>> KIANA: Anything, Kate?

>> KATE: I am going to echo what you both have said. I just, that makes sense to me. More conversation.

>> KIANA: Yeah, more conversation. I agree.

>> KATE: More conversation, absolutely.

>> KIANA: Absolutely. I agree with everything that’s been stated. I can’t say enough how important the perspectives and the narratives of lived experience counts as the expertise that balances out narratives of nonnative people for the people that they are writing about. So we in anthropology, we are unpacking a long history of communities who are subjugated, written about but not written with or not written for.

So I think part of balancing out that narrative is to consider who are we writing for? And if those communities are not a part of the audience in which I do not believe that Samoans were a part of the audience, then that’s a consideration that needs to be happening when we are talking about two perspectives.

I think we take people’s words for it, but first and foremost —

>> TANYA: I just saw her name, sorry. My mom is in the audience. Hi, Mom.

>> KIANA: But I think that’s so important for us to ensure that the communities that we are writing about if we’re not a part of them are centered in there and we are also invited into those communities to do the research that we are writing about first and foremost.

So and with that, I wish there was so much more time. I think there is so much that we have to unpack. We missed a great opportunity to have our other cohost, Doris, on our panel. We had a mixup in time zones. We are operating between four different time zones and unfortunately we didn’t get Doris’s time zone correct.

Really wish she was here. I would encourage people to tune in. I want to take the opportunity to thank everyone who has joined us today in this panel discussion and hopefully there are some takeaways that you’ve gotten from here. That concludes our discussion for today and I will hang back for the next few minutes in case there are folks that have any other questions.

>> TANYA: There seems to be another question in the question box.

>> KIANA: Oh, so they said well said. All the answers have been a blessing. Especially sitting with the gaps. (Reading the chat).

Thank you. Thank you.

>> RONALEI: Thank you, everyone.

>> KATE: Thank you all. Thank you so much.

>> TANYA: Bye.