In Spain, Scapegoating Spikes During the Pandemic

During the first wave of the pandemic, someone took a photo of a man in Seville, Spain, who had come down with COVID-19. Though thousands of people were similarly infected, this image went viral on WhatsApp, spreading symptoms of prejudice and hostility—because the man was Rroma.

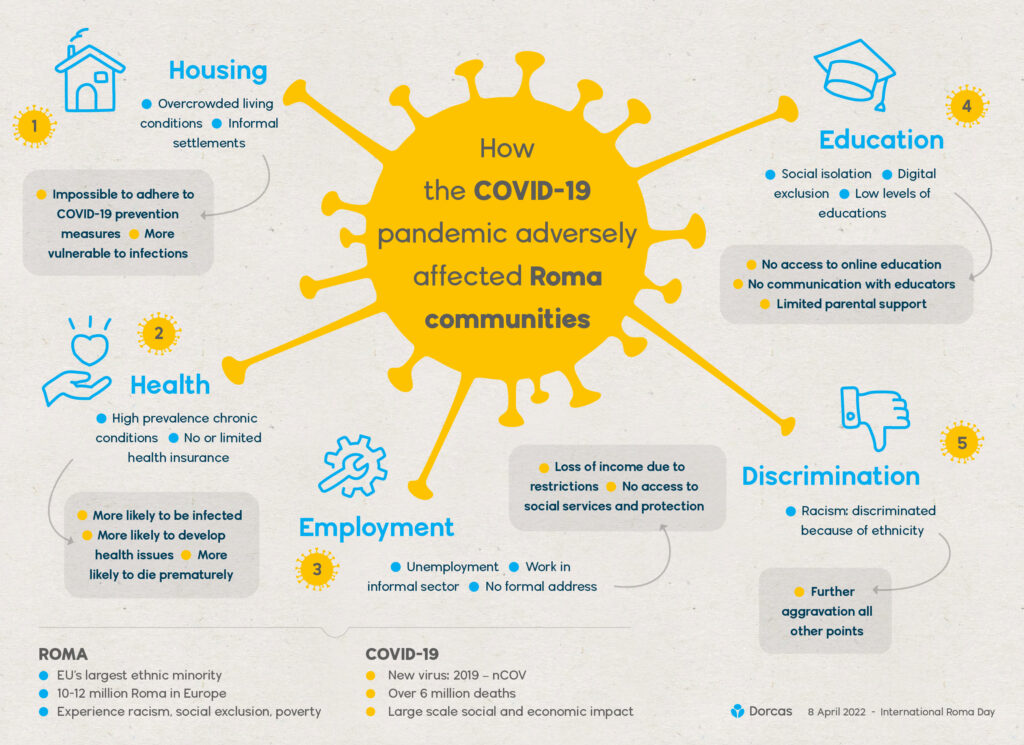

Known in Spain as Gitanos, and in English popular speech derogatorily as “Gypsies,” Rroma [1] [1] Though the spellings “Roma” and “Romani” are common, activists are increasingly using the term “Rroma” to describe themselves. This spelling is based on the Rromani alphabet, which was standardized in 1990 at the Fourth World Romani Congress in Poland. frequently suffer intense discrimination. Juana, [2] [2] All first names of Rroma people interviewed for this project are pseudonyms to protect people’s identities. a Rroma woman who lives in the same neighborhood as the man, said that after the image spread, her neighbors ran away when they saw her, even though she wore a face mask and took health precautions.

“People said nasty things about Gitanos,” Juana says. “Many assumed we did not comply with the rules and got infected because of it.” One day when Juana went to buy groceries, a neighbor shouted at her, “Gitana, go home!”

Juana’s story resonates with many Rroma’s experiences in Spain. The pro-Rroma organization Fundación Secretariado Gitano (FSG) has reported that the pandemic led to an increase in online hate speech, fake news, biased and derogatory mass media features, and police and neighbor harassment against Spanish Rroma. In the aftermath of the first lockdown, WhatsApp audios circulated widely advising Spanish people to avoid flea markets since they might catch the virus from Rroma, who have a strong presence there as vendors. Some other WhatsApp audios even called for taking action against the Rroma:

“Let’s catch them all and take them to prison … and let’s have them there, inside the walls, let them sing and dance locked up like in a concentration camp until they all die. … They are infecting everyone. … Let’s see if all those sons of the great whore, little ones, children, grandparents, and their fucking mother die.”

To offer a counterpoint to this scapegoating and misinformation, we are creating an ethnographic record of Spanish Rroma’s experiences during the pandemic and looking at how social minorities deal with stigmatization during the COVID-19 health crisis. This research project involves a collaboration between us: Antonio Montañes Jiménez, a non-Rroma Spanish anthropologist based in the U.K., and Demetrio Gómez Avila, a leading Spanish Rroma activist who has worked for the Council of Europe and the European Commission. Gómez Avila also monitors online hate speech cases for the FSG.

Though many Rroma are afraid to speak up, some decided to talk with us and to stand up for themselves and their families. The accounts gathered in our interviews are distressing and illuminate dark aspects of the social and moral crisis endured by Rroma and other marginalized groups during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Las 3000 Viviendas” is a segregated group of neighborhoods that shelter some of Seville’s most deprived residents, including hundreds of Spanish Rroma families. The streets are rough-looking, and dirt roads and crumbling buildings dominate the cityscape. When we make our way into the neighborhoods, Rroma youngsters wearing face masks greet us on the streets. As we sit on a patio, flamenco songs play in the background, and a lovely older Rroma woman offers us refreshments.

A few minutes later, we meet Antonia, a 25-year-old local Rroma woman, and her uncle Diego, her aunt Juana, and her cousin Rosi. They join us after attending the daily religious ceremony at the Rroma evangelical church.

Antonia is the first to break the ice. “Once, amid lockdown restrictions,” she recalls, “my 6-year-old daughter and I went to the local supermarket to use food vouchers an NGO gave us to provide my family with basic foodstuffs. The coupons were capital to our economic survival. You know, because of the lockdown and the pandemic, I could not sell things in the street as I usually do. My husband sometimes makes some money scavenging stuff, but he was not permitted to do so during the lockdown.”

Antonia gets teary-eyed when she recalls what happened next. “When we were queuing in the supermarket to check out our groceries, a private guard who had been following me accused me of stealing! On top of this, some local police who happened to be making their daily rounds near the store heard the hustle and joined in. Can you believe they interrogated me openly before everyone? Some neighbors of mine were there and saw the whole thing. My little girl broke down in tears as she thought they would take me to jail. They left when they verified with the NGO that my vouchers were real and that I had not shoplifted anything. Worst of all, no one apologized to me afterward.”

Following Antonia’s heartbreaking story, Rosi jumped in to narrate a no-less-disturbing incident involving her 11-year-old son, Jesús: “During the lockdowns, you know, schools were forced to transition to online teaching. My dear little Jesús fell behind his lessons because, unfortunately, we do not have the money to buy a laptop or purchase electronic devices. When the lockdown was lifted, thank God my little Jesús’ primary school bought some tablets for students.”

“One day,” she continues, “I was cooking lunch when a teacher rang home to ask me about a tablet’s whereabouts. Some teachers noticed my little Jesús’ tablet was missing from the school. To my surprise, before I could get in touch with my little Jesús to ask him about it, another teacher on the school bus accused and frisked him before his whole class. Jesús’ tablet was hidden in his low-drawer desk at school. Do you think they apologized to my little Jesús? Of course, they did not!”

Antonia’s uncle Diego could not restrain his anger when he heard his family’s account of racist experiences. “We are having a tough time of the pandemic,” he says. “It’s a dramatic situation. We have no savings, and government aid is taking too long to reach us. We are always treated like dogs. We are not even human to them. They would kill us like the Nazis did if they could. Did you read the news? They even planned to send the military to our homes!”

Diego’s remarks should be interpreted against the backdrop of mass hysteria and moral panic that involved local media reports claiming Rroma were a source of infection in the neighborhoods. In 2020, some local newspapers warned that Rroma evangelical communities were breaching lockdown measures by observing religious ceremonies. Subsequently, a video of a Rroma family celebrating an open-air ceremony circulated widely among WhatsApp users.

Amid strong concern about alleged constant breaches of lockdown restrictions by Rroma families, a high-profile public servant who acts as a consultant for policies involving slum areas in southern Seville called for the deployment of the Spanish army in “Las 3000 Viviendas” to contain the spread of the virus.

Seville is not alone in suffering from such hysteria. During a lockdown, the mayor of Santoña in Cantabria—a region in northern Spain—informed a local newspaper that he suspected some Rroma families had brought the virus to the town after attending a funeral. He declared that since most people infected in town were Rroma, local authorities must keep a watchful eye on this community.

Scholarly research on Rroma during the pandemic converges on an essential point: Spanish society has categorized people in this community as dangerous outsiders—those who do not uphold notions of what is proper or right and fail to comply with lockdowns and behave like “good citizens.”

In an anthropological study published in 2020, Paloma Gay y Blasco and Maria Félix Rodriguez Camacho found that this portrayal of Rroma people, which circulated through mass and social media, was built upon and reinforced deep-seated conceptualizations of Rroma as problematic and undesirable.

These prejudices have led to misjudgments and false accusations. Neither Jesús nor Antonia stole the items they were accused of taking. No Rroma evangelical ceremony was observed during the pandemic, but a family had decided to organize an event on their own.

Spanish Rroma’s distressing accounts of scapegoating and abuse are similar to those of other minorities worldwide.

Importantly, the moral panic about Rroma families’ alleged recurrent rule-breaking starkly contrasts with some conservative political actors’ disregard for public health and resistance to comply with the Spanish government’s pandemic policies and safety regulations. From the pandemic’s start, conservative Partido Popular leader and Madrid region President Isabel Díaz Ayuso contested the restrictions and introduced more lenient rules. She claimed her decision was based on a desire to protect Madrid’s hospitality industry, people’s freedom, and the right of individuals to have a beer in a bar at the end of a long day. In August 2020, right-wing and upper-middle-class anti-mask protesters and COVID-19 deniers rallied in the streets of Madrid, gathering 2,500 people.

Sadly, Spanish Rroma’s distressing accounts of scapegoating and abuse during the pandemic are similar to those of other minorities worldwide. Police records in the U.K. revealed a skyrocketing increase in reported hate crimes toward Chinese people at the beginning of 2020. The Asian American community also experienced a striking rise in hate incidents since the onset of COVID-19, especially following former President Donald Trump’s repeated use of the term “China Virus.”

In New York City, a Black man was violently arrested for not social distancing. Concurrently, police graciously distributed free face masks to mostly White, maskless New Yorkers who were sitting in a park.

In a study recently published in the American Journal of Public Health, researchers measured the prevalence of COVID-19–related discrimination in all major racial and ethnic groups in the U.S. Using data from the COVID-19’s Unequal Racial Burden (CURB) survey, researchers found that minorities reported experiencing more COVID-19–related discrimination than White adults. The groups who reported the highest number of discriminatory acts were Asian, American Indian, and Alaska Native people. Individuals identifying as Latinx, Pacific Islander, or Hawaiian also experienced a greater amount of discrimination.

Moreover, the historical record reveals a pattern of blaming minorities for the spread of contagious diseases. During the Black Death in the 14th century, Jews in Europe were believed to intentionally disperse the plague by “poisoning wells, rivers, and springs.” In 1900, Chinese people were unfairly vilified for an outbreak of the plague in San Francisco’s Chinatown. In the 1980s, a gay Québécois man was blamed for carrying HIV/AIDS to the U.S.

There is a systematic correlation between large-scale health crises and the rejection of minorities, which fractures societies when social cohesion is most needed.

In the face of adversity, Spanish Rroma activists and politicians have mobilized against hate and discrimination. On December 14, 2020, Spanish Rroma MPs Ismael Cortés, Beatriz Carrillo, and Sara Giménez led an ongoing initiative to create a “national pact” focused on anti-Gypsyism that seeks to provide an effective apparatus to protect Rroma against discriminatory actions. In Spanish politics, a national pact is a long-term agreement between parties represented in Congress that provides a general framework to address priority issues. National pacts must be complied with regardless of political party.

In addition, in July 2022, the Spanish government adopted the much anticipated “Ley de igualdad de trato y no discriminación,” a progressive Spanish law on equal treatment and nondiscrimination that introduced anti-Gypsyism as a crime in the Spanish national criminal code and imposes sanctions on discriminatory behaviors and offenses toward minorities.

Despite the introduction of new legal apparatus to protect the Rroma, people in Spain and around the world must keep a watchful eye on future developments. New health crises may arise, creating new scenarios in which minorities are once again scapegoated and threatened.

We think bringing together academic work and grassroots activism may make a difference. Voicing and sharing Rroma’s personal stories is a powerful tool to re-humanize this community—and, by extension, other marginalized groups—during pandemic times. It can also inform transnational analyses and anti-racist pedagogies to educate the public about discrimination during health crises—a conversation societies urgently need to tackle.