Grief Can Make Us Wise

In the first hours after the February 14 shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, we saw the same scenes of horror, shock, fear, and heartbreak replayed over and over again. As with other recent mass shootings, much of the reporting focused on the gunman, his weapon, and his strategy, as if the reporter’s work would be done once we knew who to hate.

Few are interested in supporting the sustained coverage that would be necessary to untangle the many emotions that follow such a shooting. We can’t imagine tracking the course of the grief of the victims’ families, the injured, and other survivors over the years it may take them to find hope and health after such a mass trauma. This is a shame. What we saw in those first hours was only the disorganized and confused stages of initial grief; yet it is only with the eventual acceptance of the losses, and a gradual rediscovery of meaning in life, that healing can be found.

Grief is a complex thing. Unlike anger or fear, grief isn’t a basic emotion. It is a tangle of various emotions and thoughts that may take years or even decades to work through. Several landmark studies of grief and dying in the late 1960s and early 1970s proposed that grief progresses through stages, beginning with shock, then moving through anger to bargaining, to depression, and finally, acceptance of the loss. Forty years of research on grief and grief therapy have refined this view: The grief process is now recognized as a more varied, and more personal, journey. It often involves an extended process of emotional oscillations between focusing on the loss and then on recovery as one tries to heal.

It is also clear that grief is not confined to individuals but also plays a fundamental role in society. After the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon in 2001, the entire United States suffered the national loss of our sense of security, confidence, and direction. In the case of the 9/11 attacks, we did grieve and ultimately built a memorial, a museum, and a new World Trade Center. Yet, as we learned after the Vietnam War and later in the midst of the AIDS epidemic, it is sometimes difficult for us to acknowledge our collective grief.

The Vietnam War divided the nation as no other conflict has since the Civil War. Vietnam veterans came home to a bitter debate about the war and questions about their sacrifice. America was not supposed to lose at war, and the outcome in Vietnam defied this narrative. In denial, officials failed to acknowledge the delayed health effects from chemical defoliant exposure and the long-term health issues posed by the traumatic injuries of war. At the war’s conclusion, the nation did not pause to grieve because to do so would have required us to recognize our losses.

Even today, we still do not share a common narrative for the war. But we have increasingly been able to find common ground in our sorrow. It was grief, and building a place to mourn our dead, that helped instigate the first notable reconciliation after the Vietnam War. The first major national memorial to the war was originally championed by a single veteran, planned by veterans, and funded with individual contributions. Many in the government initially did not support the memorial, and even as sponsorship increased, many elected leaders, appointed officials, and powerful individuals continued to oppose its design and placement on the National Mall in Washington, D.C.

The discussions about building the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, the resolution of the controversies over its extraordinary design, and its dedication in 1982 offered the means for those most affected by the war to share their suffering publicly. Both those who had long supported the cause of the war and those of us who opposed it had names of friends and loved ones on “the wall.” Through shared suffering and public mourning, we were able to bridge the political and moral divides of the previous decade.

Memorials can be powerful vehicles to hasten public healing and future reconciliation. They offer us places to grieve with one another, and thereafter, to talk. They start the dialogue. Soon after the unveiling of the memorial, Vietnam War veterans began to play key roles in prisoner-of-war investigations, veterans’ issues, and eventually the normalization of relations with Vietnam. The news media increasingly began to call attention to other problems such as homelessness and suicide among disillusioned veterans, and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs finally admitted, under duress, some of the many long-term health effects from the trauma of war and exposure to chemical agents.

Grief is difficult enough by itself, but when society cannot openly acknowledge or sanction the right to publicly grieve, then it becomes all the more complicated. Such a disenfranchisement of grief was not unique to those who suffered losses in the Vietnam War. In the early 1980s, many in the U.S. government ignored the emergence of AIDS for far too long, leading to the indefensible deaths of tens of thousands of U.S. citizens and the unwitting spread of the disease. Our president refused to even say the word “AIDS” until three years after its first recognition in national journals and newspapers. Only when it became a problem in the broader community, not just the gay community, could we no longer ignore or deny its causes.

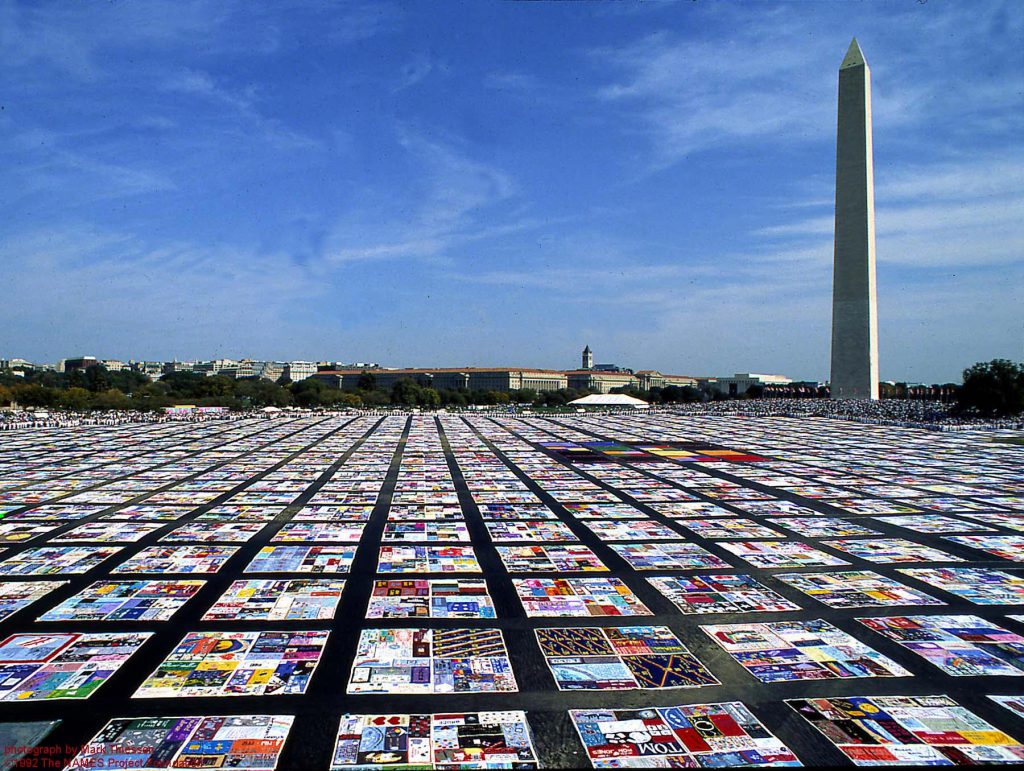

Five years after the wall was dedicated, those most affected by the AIDS crisis recognized that they too needed a national act of mourning. In October 1987, the AIDS Memorial Quilt, which, like the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, named the dead, was laid out for one weekend on the National Mall. There were 1,920 individual panels that measured 3 feet by 6 feet, each remembering and honoring someone who had died of the disease. In that year alone, the U.S. toll for AIDS deaths was at least 13,329. The weekend it was on display, over half a million people went to see the quilt. A year later, the quilt returned to the mall with 8,288 panels, covering an area larger than four football fields.

Mourning the dead unexpectedly cut across political, religious, and moral divides. All segments of society, from young children to Hollywood movie stars, were represented in the panels. The AIDS quilt traveled around the country, and panels were added everywhere it was displayed. Public grief, alongside lobbying by activist groups, served to mobilize widespread public pressure to address the crisis. Bipartisan support increased federal funding for AIDS research, prevention, and treatment from US$900 million in 1987 to US$7.7 billion 10 years later.

We and our leaders clearly can acknowledge grief when we sense that we are attacked by foes who are willing to crash planes into downtown buildings in Manhattan or explode a truck in front of a building in Oklahoma with a daycare center in it. We are experienced at acknowledging the grief of these kinds of losses and building memorials to national tragedies such as 9/11 or the Oklahoma City bombing. But all too often in this nation of the “American Dream,” we fail to give the right to mourn to those whose friends and loved ones have died in tragedies for which we do not share a common narrative about our loss, much less agree on what we will do to address that loss. By disenfranchising this grief, we merely compound our losses.

We must recognize the need to grieve in all cases of mass trauma and public tragedy.

As a man in his mid-60s who has lived through the Vietnam War and the AIDS crisis, and who has been devastated by my own personal losses of loved ones to suicide and depression, I know the necessity of grief. And as a professional archaeologist who has been involved with the repatriation and reburial of Native American remains, I have witnessed the power of collective grief in unifying tribal elders as they worked to have ancestral remains returned from museums for appropriate reburial. As a society, we must recognize the need to grieve in all cases of mass trauma and public tragedy.

Politicians and the news media are wont to gloss over the challenges posed by tragedies such as the recent mass shootings in Parkland, Florida; Sutherland Springs, Texas; and Las Vegas, Nevada—and the underlying issues inherent in America’s gun violence. They certainly do not acknowledge the complexity of grief and the long road to healing. By meeting public grief head-on, we can acknowledge our suffering and possibly even build bridges as a society to confront difficult and divisive national problems. It’s possible that our grief over national tragedies may be one of the few patches of common ground left where we can embrace one another in this deeply divided time.

There will be no easy fix, but grief should energize us to move toward reconciliation and new wisdom. We cannot end the process in the middle of confusion and anger. And we must find new practices, or rediscover old rituals, to support those most closely affected by tragedy as they grieve. We need to ensure their safe journey through grief, the most difficult of emotions.