How Sweat Lodge Ceremonies Heal War’s Wounds

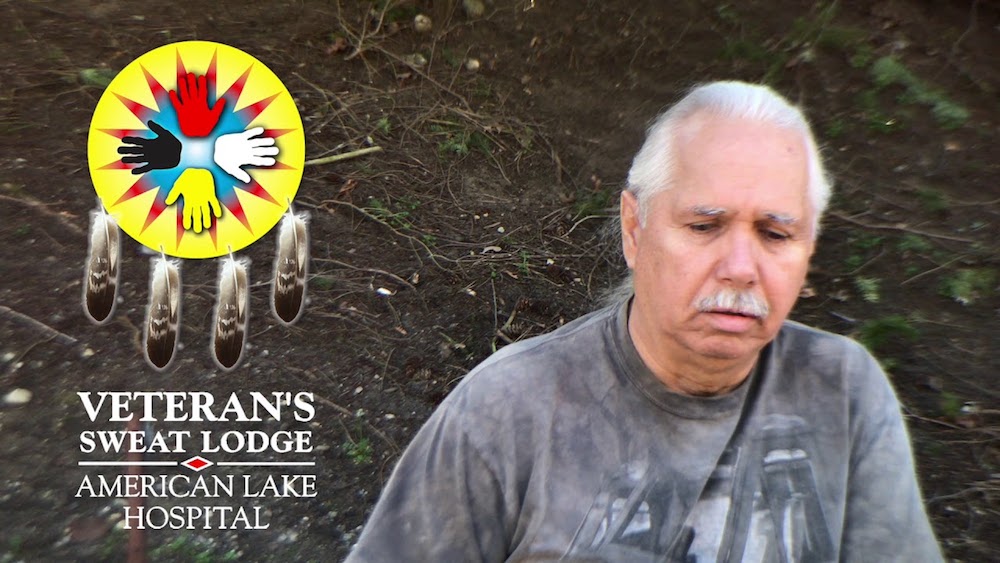

When I arrived for my first Native American Sweat Lodge Ceremony in 2016, I was greeted and warmly embraced by Marty, a person of mixed tribal ancestry. He had long black hair and wore a T-shirt that read “Veteran’s Sweat Lodge.” When, earlier, I had contacted him and asked about attending a ceremony, I worried that I might not be welcome as a White man. I also had concerns that my status as an anthropologist, with the field’s long and problematic history with Indigenous people, might make some uncomfortable. He assured me that any veteran with a PTSD diagnosis was welcome—a criterion I meet.

“Our belief,” Marty told me, “is that if you are here, it is because Creator brought you here.”

Since my discharge from the U.S. Army a decade before, I had suffered from nightmares, hypervigilance, anxiety, depression, and a litany of things that were all attributed to “post-traumatic stress disorder” by clinicians, friends, and family. Clinical PTSD therapy did help me cope, to some degree. I learned to identify my triggers and avoid them when possible, significantly reducing my experience of PTSD episodes. I was temporarily prescribed medications that, in spite of some unwanted side effects, reduced nightmares. These changes did help me improve the livability of my day-to-day life.

But I continued to suffer in ways that were not addressed by PTSD therapy. As an example, one approach of that therapy—cognitive processing therapy—helps people identify and correct mistaken beliefs about the world that were incurred during a traumatic experience. In time, I learned that I suffered from guilt. My guilt was rooted not in mistaken beliefs about the world but rather in my sincere belief that there was something fundamentally wrong about both the war I had participated in and my role in it.

The greatest labor of my postwar days was the unwieldy and ungratifying effort to try and live with myself.

The Native American veteran’s healing community at the American Lake Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Washington state has assisted thousands of vets since it was established in the 1980s (with a couple of breaks in continuity). What originally began as a way for the VA to provide help for Native American Vietnam War veterans who were not recovering from PTSD through clinical therapy has now become a healing path for a diverse set of veterans, including me—sometimes with remarkable outcomes.

Marty smudged me with sage smoke and guided me onto the sacred ceremonial grounds on the shore of American Lake. He began to introduce me to a world animated with spirits and sacred beings, and a worldview different from the one I was carrying with me.

As we waited for stones to heat up in the sacred fire, elders and experienced participants taught me how to make prayers, wrapping offerings of tobacco in diverse colors of cloth, which are used for different kinds of prayer. They patiently explained how to show respect to the sacred fire burning near the entrance to the sweat lodge before taking me in to sit in a tight circle with other participants. (Most were Native American, but there were a few other White veterans like me.)

One by one, several red-hot grandfather stones were brought into the lodge and placed in the center. The flap to the lodge was closed, and we were enveloped by complete darkness, except for the dim red glow of the heated stones. Medicinal herbs and water were sprinkled over the hot stones. The lodge filled with the scent of the burning herbs, and our lungs inhaled the hot, pungent steam. Drummers in the lodge began to drum and sing, and over the next several hours, we sang and gave passionate prayers. That first ceremony was intense—almost overwhelming—but it was the first of many and the beginning of a healing journey that would change my life.

In 2006, I was wounded in combat in Afghanistan and retired from the Army due to my injuries. When my personal and academic concerns with trauma led me to anthropology, I began to dig into the complexities of PTSD and war. For two years, I traveled back and forth between my home in North Carolina and Washington state to visit the Sweat Lodge Ceremony and community. Then for seven months I lived in Washington and immersed myself in the community there.

Approximately 11–20 percent of the 2.8 million veterans who have deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan in the 21st century have been diagnosed with PTSD—but more than double believe they also may have PTSD. Up to 67 percent of veterans who undergo first-line psychotherapies for PTSD experience little reduction in their symptoms.

While the valid biomedical framing for post-traumatic stress can account for much of this suffering, the diagnosis comes up short when sufferers are confronted with weighty questions about how masculinity, violence, guilt, ethics, belonging, and many other things inflect the experience of trauma.

As one regular participant in the sweat lodge put it: Military culture creates dangerous expectations, among other things. “Military culture teaches you that it’s never enough,” he explained to me, talking about a kind of death drive that is cultivated in the competitive, violence-ridden world of soldiering. In that world, he said, anyone who doesn’t die on the battlefield can internalize the belief that their sacrifice and effort was inadequate. “You start to believe that death is the only real achievement. It drives veterans to bad places.”

In 1980, when PTSD was recognized by the American Psychiatric Association, it was partially in response to the conspicuous suffering of Vietnam War veterans. For many of those who had felt shunned for their involvement in the war, for not “getting over it,” or for being a “loser,” the biomedical legitimation of PTSD came as a relief.

Framing the symptoms of combat trauma as an amoral “disease” was welcomed not only by veterans but also by other sufferers of trauma. Prior to the formal medical recognition of PTSD, institutions and the public tended to view trauma-related suffering as a kind of weakness. But as much as the diagnosis legitimized real experiences of trauma, therapies rooted in PTSD’s biomedical framing were limited.

Notably, PTSD therapy was often ineffective for Native American war veterans. In response, tribal leaders requested that the VA provide (or give them space to provide) traditional Indigenous treatment for Native American veterans.

The VA did so, justifying their decision on the belief that Native American veterans were rooted in “warrior cultures.” On this basis, the administration presumed that Native American veterans understand war, trauma, and healing differently than mainstream American culture. It was expected that such warriors would benefit most from warrior-specific practices.

In fact, the projection of assumptions such as these onto Indigenous people contributed to the distinct kind of suffering that the Native American ceremonies at American Lake were designed to heal.

Of the 200 or so people who come through the sweat lodge each year, perhaps half are Native American. Participants are a mix of “regulars” who have attended ceremonies there for years, residents of the inpatient PTSD clinic at the hospital, and a multiethnic and multiracial group of veterans who are seeking alternative ways to heal from PTSD after other approaches have failed. A council of a half dozen Indigenous elders, one of whom is Marty, oversees the ceremonies at American Lake.

Early in my research, an elder explained to me that much of what is addressed in the Sweat Lodge Ceremonies concerns violent notions of manhood that were and are lionized in colonialist Euro-American society. An early goal of the community was to work through the ways that these norms were sewn into Indigenous peoples during the process of colonization. But elders also realize that these same norms are sewn into the bodies and souls of Euro-Americans, particularly that society’s men, and all others whose lives are shaped by such norms.

Over the next several hours, we sang and gave passionate prayers.

Thus, the same ceremonies that help Native American veterans heal help veterans of European ancestry as well—though I was reminded of the importance of being conscious of the unique trauma experienced by Indigenous peoples.

Today the Sweat Lodge Ceremonies at American Lake are the center of the healing community. They run about three hours (give or take) and weave together prayers, songs, teachings, herbs, and restoring one’s sense of connection to the people, places, and spirits around them.

While conventional clinical PTSD therapy focuses on nerves, triggers, and learning to silence inappropriate reactions to stimuli, the approach used at American Lake identifies a different source of suffering. Emphasis is placed on the sickness that comes from fighting people, which is called iwáyazaŋ azúyeya in the Lakota language. Both in society and in war, we experience antagonistic relationships with other people and these experiences make us suffer. This concept of illness applies to all facets of life, not just on the battlefield. (See sidebar by Elder Michael “Mike” Lee, the ceremonial leader at American Lake.)

I do not intend to dismiss the validity of the PTSD diagnosis. PTSD is viewed as a biological response to surviving terrifying or near-fatal situations. The mind and body remember these traumas and go into fight-or-flight mode when stimuli, called “triggers,” convince autonomous systems in the body that it is in a similar danger. It is a helpful adaptation for survival in adverse times but becomes a problem when benign stimuli intrusively trigger people during daily life.

Despite the progress I made in clinical PTSD therapy, there were other things I could not escape. Confusion about what had happened and why—and trying to account for my role in it all—became tortuous, consuming me like a parasite from the inside out. The evil, unjustifiable violence of the war I had fought was something I could not avoid. I wrestled with this not only in my nightmares but every day at work as I committed myself to the scholarly study of war, colonialism, and trauma.

Today the rituals at American Lake are no longer seen as specific to Native American veterans. Likewise, non-Native veterans no longer see “warriors” as something different from them. Though uncommon prior to the 21st century, the term has been widely embraced by contemporary veterans and others, such as domestic police (an approach and mindset that has recently come under well-deserved scrutiny). For veterans, they see themselves as warriors and less so as “citizens who served.”

Veterans who embrace the term warrior use it to mean a distinct kind of person, often imagined as a privileged caste in “warrior cultures” throughout human history. In contrast to WWII veterans who returned to the U.S. from war with the intent of strengthening their nation as civilians, contemporary veterans who embrace a warrior identity often feel an “otherness” in relation to civilians. They come home with the intent of continuing to be warriors, strengthening their society through maintaining their inherent martial values.

This worldview has been reinforced by contemporary literature and media. One analogy for this, already popular from retired Lt. Col. David Grossman’s 2004 book On Combat, achieved ubiquity after it appeared in the 2014 film American Sniper. This analogy posits that there are three kinds of people in the world. The vast majority of people are “sheep,” who are virtually helpless and naïve about the dangers of the world. The remaining people are either “wolves,” who prey on the sheep, or “sheepdogs,” who protect the sheep from the wolves.

In applications to U.S. society, the sheep represent the majority of citizens. Wolves are the criminals, terrorists, and gangsters who are seen as constantly trying to penetrate our borders. The sheepdogs are the “warriors” of our society, a category that not only includes military personnel but increasingly domestic police as well.

In his book, Grossman explains that the sheepdogs should expect to be disliked by the sheep for their brutality and disagreeable nature. But, he argues, the sheep do not realize how helpless they are and that it is only through the violence of the sheepdogs that they do not become the immediate prey of wolves.

Grossman has been training police for two decades to think of themselves as warriors. Recently, he has come under heavy criticism for his “bulletproof mind” training program that teaches cops to kill with less hesitation.

“Often, the goal was not even to kill but rather to take the enemy’s spirit—challenge their bravery,” says ceremonial leader Elder Mike Lee.

When I first went to American Lake, I wondered if such notions of “warriordom” might inspire non-Native veterans to pursue healing in the sweat lodge community, seeing it as a form of warrior-specific therapy. As warriors who distinguish themselves from civilians, some vets can imagine postwar suffering to be unique and transcendent of PTSD, which can be experienced by civilians due to ostensibly less “profound” forms of trauma that can be treated by biomedicine in a clinical setting.

From my conversations with first-time attendees, I have learned that some veterans are attracted to the ceremonies for this very reason. But what unfolds transcends their preconceived notions. Far from a macho-warrior event where men demonstrate their strength and capacity for pain, the ceremony escorts veterans through something deeper and potentially more challenging—a journey that’s more like an unraveling.

Mike Lee, the elder who leads ceremonies at American Lake, grew up on the Blackfeet Reservation in Montana and is a veteran of the Vietnam War. Many times, I have heard him share his wisdom with new attendees before they go into the lodge for the first time. In addressing the notion of “warriordom,” Lee explains that the English word “warrior” is an artifact of European worldviews and Hollywood. It fails to adequately describe many of the Indigenous peoples, including his own ancestors, to whom it is applied.

Even within contemporary North American society, Lee cautions that “a ‘warrior’ and a ‘soldier’ or ‘veteran’ are not exactly the same thing.” The overwhelming brutality of Euro-American war, where people travel far from home and lay waste to foreign people and lands, would be incomprehensible to his ancestors. Lee explains, “Often, the goal was not even to kill but rather to take the enemy’s spirit—challenge their bravery.”

Lee’s teachings provide a cultural context for understanding the suffering that people experience. The American Lake approach has less to do with treating a medical diagnosis and more to do with how the violence and alienation of modern society, along with toxic frames for masculinity, Indigeneity, and race, harm the men and women who work to uphold notions of “manhood” in both war and everyday life.

Iwáyazaŋ azúyeya is, perhaps, beyond the scope of clinical therapy or conventional biomedicine. However, it is not seen as being specific to a warrior caste.

Oriented to a different cosmology than what most Euro-Americans hold, the teachings convey to attendees that the expectations of manhood and warriordom are not inherent; they are culturally constructed.

While Euro-American societies often have a “law and order” view of the world, which means some veterans are unable to forgive themselves for their battlefield actions, the alternative proposed is a worldview that emphasizes adjusting and getting back to life through recognizing what happened and seeing it from a new point of view.

That new point of view offers a spirit-oriented perspective: that humans (and all living beings) are spirits who come to this world to live and interact, and then cycle out of it to return to the spirit realm.

So, for veterans who have killed or hurt others, the teachings from American Lake, which are shaped by the cosmologies of Plains tribes, may shift their sense of themselves and others. Elders focus on learning from horrific experiences—not carrying guilt and self-hate about one’s past actions. They emphasize moving on to become better people who do not harm others.

For many participants, the Euro-American cultural understandings that can create painful dilemmas—and that also frame that suffering as “PTSD”—simply begin to fall apart.

The Sweat Lodge Ceremony and other rituals are purifying or cleansing people from the sickness that comes from fighting other people (and the self). Faced directly, the experience of being afflicted with one’s own violence is understood, and attendees are accepted with a kind of guaranteed belonging that is unlike anything I have observed in my own society, including in my experience in the military. A sincere, radical belonging is virtually promised to attendees provided they respect and adhere to the ritual decorum of the sacred grounds.

During ceremony, in the lodge’s intense heat, the combined sense of vulnerability and non-judgment overcame me. I could sense people around me experiencing the same thing. We shared in one another’s suffering, liberated by the radical belonging offered in that place and in concert with trust in the confidentiality we promised to one another. One by one, the iwáyazaŋ azúyeya in each of us came out.

Mine was guilt.

In the years that have passed since that first ceremony, I have met spirits, had visions, and have been led to understand my relationship to the world around me in a way that has made my life more livable.

Belonging and connectedness are central to what participants receive at the American Lake community. As one participant said to me: “They know the importance of recognizing the human that exists in us all. You learn to see the fundamental good in people … even in yourself.” A committed group of Indigenous people share their worldview, giving attendees a new set of eyes with which to view and understand their place in the world.

Three and a half years after my first Sweat Lodge Ceremony, the new set of eyes I gained have not only helped me learn to live with myself, but also to live better with the world and all of the spirits and beings who inhabit it.