The Truth About “Sustainable” Palm Oil

In May 2016, Petrus, a 3-year-old Marind boy from West Papua, Indonesia, died of dysentery after drinking river water contaminated with pesticides from a nearby oil palm plantation. [1] [1] All names except the author’s have been changed to protect people’s privacy. Petrus’ grieving parents, Marina and Bernardus, carried their child to the company headquarters some 20 kilometers away. They asked that the young boy be buried in their clan’s ancestral graveyard, located within the newly established oil palm concession. The company refused. The land was now their property, they argued. Burying the child within the plantation would attract pests that would harm the oil palm trees.

Bernardus and Marina then pleaded for Petrus to be buried in the concession’s conservation zone—a 10-meter-by-20-meter patch of sago palm grove amid a sea of monocrop oil palms—so the child could rest with his plant and animal kin. This request, too, was denied. In the interest of protecting local flora and fauna, access to the conservation zone was prohibited for non-company personnel.

Finally, Bernardus and Marina buried their child a few miles outside their village and plantation, by the side of the Trans-Irian Highway. Since then, the couple told me, their nights have been haunted by nightmares of Petrus’ frail body being trampled by trucks overloaded with palm oil fruit and by bulldozers clearing the forest to make way for oil palm. The parents wept as they described how isolated and frightened Petrus appeared in their dreams, alone by the dusty highway and severed from his plant and animal kin, never able to find rest.

“Since oil palm arrived,” Marina explains, “we Marind people have been robbed of our forest. The oil palm companies cut the forest. They also protect some forest. But now, all of the forest belongs to the companies, and we Marind have no place to live or die in peace.”

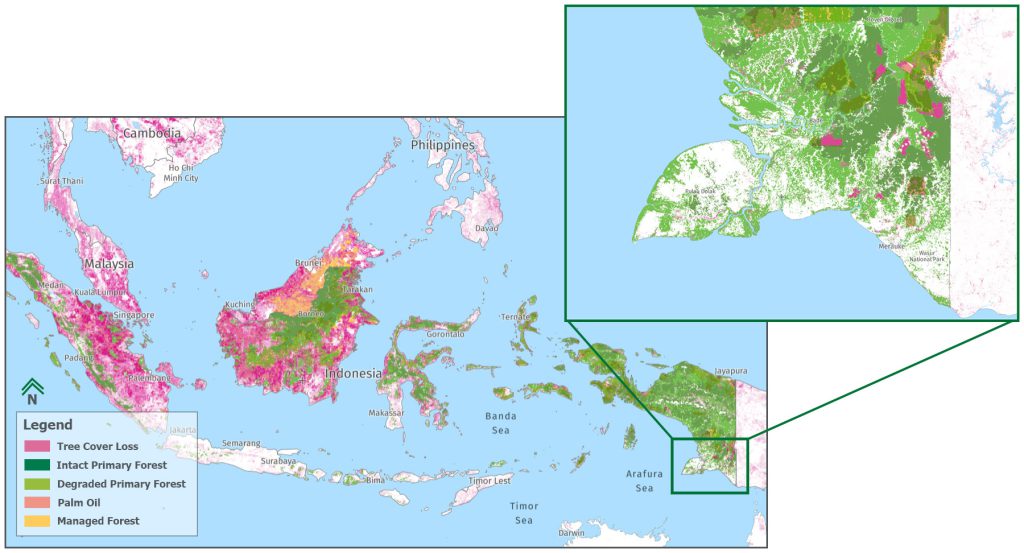

In recent years, the public and nongovernmental organizations have raised an alarm over palm oil, an ingredient in close to half of all packaged goods globally, according to the World Wildlife Fund. The palm oil industry burns biodiverse forests, poisons rivers with pesticides, appropriates Indigenous peoples’ lands, exploits workers, and destroys orangutan habitat. The outcry has led to the emergence of “sustainable” palm oil certification standards.

Yet despite their purported benefits, “green” palm oil initiatives are often criticized by Indigenous peoples, who find themselves dispossessed or displaced by agribusiness. Among Marind communities in the Merauke district of West Papua, where I have been carrying out fieldwork since 2013, these projects give rise to consternation, frustration, and sadness. They disconnect the Marind from their ancient relationship with forest organisms they view as kindred spirits and as companion species in both life and death.

“People think palm oil is green because there are conservation projects. But no one sees the blood and the violence,” says Perpetua, a young Marind woman. “Protected, not protected—it doesn’t matter. All that land was taken from us without our permission.”

A Marind elder named Pius points out that in so-called sustainable palm oil projects, conservation scientists from outside the area who “have never lived with the forest” are hired by palm oil companies to evaluate the plantations. These conservationists compartmentalize the landscape into zones of high and low conservation value based on guidelines set by the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil. Areas of high conservation value include forests that house threatened species or protect watersheds, as well as sites that satisfy the needs of local communities—though this latter aspect tends to get neglected. Companies are then required to demarcate, monitor, and enhance areas deemed to be of high value.

But what distinguishes high and low value zones is unclear to the Marind. The “experts,” Pius says, do not understand that plants and animals depend upon diverse ecologies—swamps, marshlands, mangroves, savannahs, forests—that are all equally important to their subsistence, reproduction, and growth. When only certain ecosystems are considered worthy of conservation, those that fall outside this category become “sacrifice zones” assumed to be available for exploitation. Meanwhile, the absence of ecological corridors connecting conservation patches limits the capacity of organisms to travel in search of food, water, and mates.

While plants and animals are restricted to bounded zones, the Marind find themselves excluded from areas where they once hunted, foraged, and fished. Conservation areas are often caged by barbed wire and remain strictly out of bounds for non-company personnel. This limits the capacity of the Marind to access forest foods and resources.

More importantly, this segregation disconnects the Marind from their relationships with plants and animals, just as Petrus was separated from his forest family. These sylvan organisms, described by my interlocutors as “grandparents” or “siblings,” are believed to share common descent with the Marind from ancestral spirits. They are considered agentive, sentient beings, with whom the Marind entertain relations of mutual care and respect.

Plants and animals provide humans with food and other resources. In return, humans support the growth of their non-human siblings by enhancing their environment. Villagers open pathways in the forest for wild pigs to access water sources, scatter seeds to promote tree growth, and periodically burn vegetation to enhance soil nutrients. These reciprocal acts of care—celebrated by the Marind in myths, stories, and songs—enable humans and their non-human kin to survive and thrive.

In contrast, species severed from their relations to humans in the name of conservation are a source of great sorrow for the Marind. Most notable is the sago palm, which yields their staple carbohydrate, sago starch. The plant holds central significance in Marind myth and culture, and is associated with invigorating “wetness” (dubadub) and fertility. Humans sustain the sago palm through a range of direct and indirect actions.

For instance, villagers help parent palms and their suckers access nutrients and sunlight by pruning suckers, clearing dead fronds and weeds, thinning the canopy, and burning excess vegetation. Transplanting suckers, or “sago children,” helps them grow by giving them access to water and light while allowing parent palms to regain their regenerative capacity. These suckers are often given the name of the individual who transplanted them, so that, in the words of Evelina, a young Marind woman, “suckers and humans remember each other and share the same story.”

Sago palms that grow in conservation zones are an object of pity among many Marind. No humans can help them care for their sago children or make their environment more conducive to healthy growth. Since selective felling and transplanting cannot take place, palms reproduce sexually rather than vegetatively. This ends the life cycle of the parent palm, whose seeds disperse across great distances and germinate far away from their sago kin. Exiled from each other, seeds and parents become “dry,” “lonely,” and “sad,” many Marind say.

Sequestering palms to conservation zones also means community members can no longer hunt within the forest or process sago flour. This negates the possibility of creating shared memories and relations between people and palms. As another Marind elder, Gerfacius, explains, “When sago and humans grow apart, they suffer because they can no longer share wetness. They can no longer make stories together. They can no longer support each other’s lives.”

Conservation practices in agribusiness are problematic for the Marind—and for many other Indigenous communities—because they assume humans are agents of ecological disturbance, so biodiversity can best be protected by divorcing ecosystems from people. This model is premised on an image of nature as an untouched zone of “wilderness” that should be kept pristine and free of human influence. Conservation efforts then snatch these landscapes away from the local communities who know them intimately.

These projects are designed and implemented by scientific experts from outside Merauke who rarely consult the Marind. These specialists ignore the fact that human partnerships with forest ecosystems may enhance biodiversity while fulfilling the needs of Indigenous people. In short, the violence of conservation in this arena lies in its failure to appreciate the symbiotic relationship between humans and the multispecies society that constitutes the natural world.

In addition, the sustainable palm oil sector perpetuates colonialist-like top-down, extractive violence—in an environmental guise. In Merauke, oil palm expansion is taking place without the free, prior, and informed consent of Indigenous landowners. Many community members have been forced to surrender their territories to oil palm companies under duress and in exchange for derisory compensation. Collusion between the Indonesian military forces and local oil palm corporations is rampant. Promises of social welfare have rarely materialized. With most companies bringing in their own labor force or hiring non-Papuan settlers, few Marind can make a living from working in the plantations.

A key step is giving a voice to Indigenous peoples in the design, implementation, and monitoring of conservation schemes.

Local communities’ understanding of their rights under national and international law is also limited. Customary land rights, while enshrined in provincial laws, are not recognized or respected on the ground. Villagers who voice their opposition to agribusiness projects are routinely harassed, intimidated, or accused of bearing independentist aspirations. At the time I wrote this piece, people in the community reported to me that more than a dozen members had been incarcerated for refusing to surrender their lands to oil palm corporations and had their ID cards confiscated indefinitely.

Against this backdrop, sustainability-driven conservation initiatives offer little solace to the Marind because they obscure the dispossession and disempowerment suffered by Indigenous communities as a result of oil palm expansion. It comes as little surprise, then, that many Marind consider protected areas and agribusiness projects to be two sides of the same coin. As Yosefus, a Marind elder, says, “Capitalism, conservation—they both exclude us. Capitalism, conservation—it’s the same thing.”

How, then, can conservation work more effectively in the palm oil sector? A key step is giving a voice to Indigenous peoples in the design, implementation, and monitoring of environmental protection schemes. Conservation practices should be informed by the traditional ecological knowledge of locals, who have learned over many centuries how to sustainably use forest resources. These practices should also acknowledge that, for communities like the Marind, the forest is more than just a material environment to be either exploited or preserved. Rather, the forest is a living space shared by plants, animals, and humans who are bound by emotionally charged and morally valued forms of kinship and care.

Palm oil conservation initiatives must acknowledge the right of Indigenous communities to give or withhold their free, prior, and informed consent to oil palm development. Unless this consent is sought and respected, sustainability will mean very little to those who end up excluded from natures both exploited and preserved.

Greening the palm oil sector requires that agribusiness corporations, governments, and conservationists rethink the place of humans within the natural environment and the meaning of nature itself across different cultural and geographic contexts. Doing so may bring the palm oil sector one step closer to reconciling the social and environmental dimensions of cash crop sustainability. As Marcelina, a young mother of three, puts it, “Conservation is not just about nature. Conservation is also about people.”