What Problems Does Organic Cotton Solve?

One warm afternoon several years ago, I was walking with Korianna, a farmer in Telangana, India, when I smelled something bad. [1] [1] All names except the author’s have been changed to protect people’s privacy. The scent of diesel and sulfur wafted over the dusty red clay and fertile black earth characteristic of the Deccan plateau. Korianna pointed to fields of tightly planted, vibrant green cotton in the distance, where a neighboring villager was using a motorized sprayer to unleash pesticides onto crop rows. “When they start to face losses, they’ll want to join us,” he told me.

Telangana farmers grow about 15 percent of the cotton produced in India, but the South Indian state has faced exceptional scrutiny for toxic chemical overuse, high costs, and conflicting stories about yields. Most farming families grow a combination of cotton, rice, and maize, but cotton—the most remunerative crop—dominates. Around 95 percent of all the cotton seeds sown in India are Bt seeds: genetically modified and bred to grow best alongside fertilizers and pesticides.

But Korianna was bucking the trend and growing organic cotton using non-Bt seeds.

Korianna first heard about organic farming in the 1990s. Back then, his own fields used to smell like his neighbor’s—thick with endosulfan and chlorpyrifos, common cotton pesticides now phased out by manufacturers and stockpiled by farmers. For years, he had watched his chemical costs tick up as his yields remained stubbornly low. With morbid curiosity, he started reading newspaper stories about failing harvests, toxic landscapes, and rising debts. Then came stories about farmers from nearby towns dying by suicide, a complex and persistent problem in Telangana, where social pressure to succeed is high.

Fed up, Korianna and a few others in his village agreed to partner with a local nongovernmental organization dedicated to reducing pesticide exposure. He started hanging lights and pheromone traps to attract adult insects to flypaper. He also concocted foul-smelling mixtures of garlic, cow urine, and neem oil to kill juvenile grubs.

To his surprise, the system worked. Over the next few years, the entire village abandoned chemical pesticides and fertilizers. They began marketing their crops as organic produce in Hyderabad, the nearby capital.

Going organic meant Korianna and his neighbors had to adapt to significantly lower cotton yields. But they made sure the switch came with other perks that helped make up for the loss. By buying into a version of environmental development that appeals to consumers in the growing market for organic and ethical clothing around the world, farmers can gain subsidized work and, importantly, new kinds of social clout.

Korianna, for instance, was hired to work for the NGO in his village. Part of his job included speaking with visiting scientists, donors, certifiers, interested farmers—and anthropologists like me.

During five trips to Telangana from 2012–2018, I spent 16 months documenting farm biodiversity and asking farmers about their experience with GM and organic cotton. In all, I asked over 500 farmers to explain their decisions in planting more than 5,000 seeds. Following many of these farmers over several consecutive growing seasons, I tracked years of decision-making and untangled what sorts of things work, and for whom, in sustainable smallholder agriculture.

What I learned from spending time with farmers like Korianna might surprise people who are used to thinking about development as a technological rather than a social problem. Organic development projects do not work because they are inherently better or more just. Where and when they work, they do so because they provide an alternative way to live well as a farmer in today’s unequal global economy.

Though genetically modified Bt cotton continues to dominate Indian agriculture, organic methods are gaining in popularity. Indian farmers now provide about half the certified organic cotton sold in global markets.

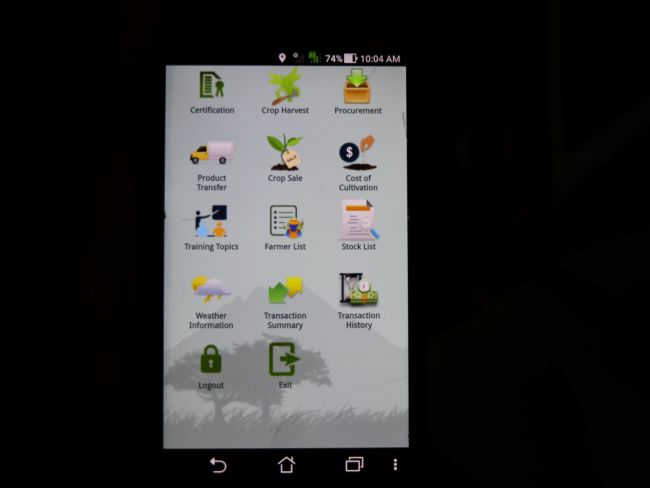

Organic cotton goes through a rigorous process before entering a long, complicated supply chain. First, the seeds must be carefully sourced from non-Bt seed breeders. Then they must be grown and harvested according to certified organic methods. Next, the cotton must be ginned and spun in facilities uncontaminated by errant Bt threads, then washed, dyed, cut, sewn, and, finally, sold to conscientious consumers based mainly in Europe, North America, and Japan.

Organic distributors sell these harvests by telling consumers they are helping farmers who are isolated, poor, and in crisis. This narrative is not misleading. Korianna, like most in his village, belongs to the Dalit community, comprised of members of historically disenfranchised Hindu castes. Many organic development groups recruit Dalit farmers, along with Adivasi farmers—members of Indigenous tribes—because these groups have had and continue to have poorer access to key state infrastructure.

But the story is complicated. It is not global organic consumption that provides the clearest benefits to these farmers so much as the community support the consumption sustains. This support is critical, especially for marginalized groups that have historically been left out of the development schemes that have led to economic growth in other sectors of Indian society.

Organic agriculture has provided farmers a public platform to enact their own vision of sustainable development.

During the Green Revolution of the 1960s and ’70s, for example, some farmers in India received packages of irrigation, fertilizers, pesticides, and seeds bred to respond to water, fertilizer, and chemical management. Funded through international partnerships and development NGOs such as the Rockefeller Foundation and then distributed through the Indian state, these new tools transformed farming for the nation as a whole. However, many of the economic and infrastructural gains went to the most privileged farming families, while Adivasi and Dalit communities continued to lack the resources that made this kind of farming profitable.

Over the past 50 years, agricultural development in India and throughout much of the world has stressed increased production and lower prices. To accomplish these goals, the emphasis has been on consolidating rural resources and encouraging farm families to move to cities and work in manufacturing, service, or the digital economy. Since the 1990s, liberalized economic policies and the growth of these new economic sectors have indeed made India wealthier—especially in urban areas.

Yet hundreds of millions of small farmers persist in India; around 50–60 percent of the country still earns its primary living through agriculture and related work. Small cotton-farming communities in India face not only the depopulation and consolidation felt by rural areas around the world, but also generational disparities in land ownership and steep competition from larger, subsidized, mechanized cotton farms in China, the U.S., and Brazil.

And even farmers in North India who initially benefited from the Green Revolution have struggled to make a decent living recently—a point made clear by ongoing protests by farmers challenging new farm bills pushed through by the central government in Delhi.

Monocultures of cotton and other crops encourage agricultural extraction, which reorders soil composition, plant diversity, human labor, chemical investments, land leases, drilled water, and the farm economy itself into a series of investments to maximize yields. This vision of agriculture ignores larger costs: exhausted soils, falling water tables, chronic pesticide exposures—all mortgaged against a web of ecological and economic relationships. This extractive agriculture is only becoming more difficult to sustain with changing weather patterns due to climate change.

Organic cotton farming needs to be contextualized within these larger patterns of investor-driven rural development, generational poverty, and the inequalities of global agriculture. Only then can people interested in sustainable agriculture understand why and how these programs succeed or fail to improve the lives of people who participate in them.

As we drank sweet black tea in front of his house one day, I asked Jenaram, “How are your yields?” A half-dozen fat chickens scratched at the compost pile in his mother’s vibrant vegetable garden. I was spending a few weeks speaking with organic farmers in his region, and I often returned to Jenaram because we enjoyed talking about biodiversity and soil science.

“They’re lower than my neighbors, especially in the first few years of organic farming,” he answered, “but that’s not what this is about.” He waved the question aside, prompting one of the chickens to flap its wings in alarm.

“More important are the benefits that we get for our health and to this health.” He gestured around the farm, which contained dozens of plant species, a stark contrast to the cotton monocultures that dominated the regional landscape.

Much Telangana farming is defined by a Telugu catchphrase: manci digubadi annukunthunnanu. Literally, “I’m hoping for a good yield,” the saying compresses a range of agrarian aspirations: the hope to reap a profitable harvest, to afford school fees, to throw lavish weddings, or to pass on land as a meaningful inheritance to one’s children and grandchildren.

So, it was significant that the organic cotton growers I met in India accepted substantially lower yields, sometimes half what they would reap per acre using chemical-intensive methods.

Still, according to Jenaram, avoiding pesticides was more important than increasing yields. He had a bachelor’s degree in science; when he spoke about the risks of pesticide sprays for the village’s long-term ecology, fellow farmers listened.

Besides, going organic brought other harvests to these communities: seeds, training, farm equipment, water pipelines, interest-free loans, and more. These perks came from NGOs, like the one Korianna worked for, or through the connections and government programs that NGOs facilitated.

Korianna, Jenaram, and other local leaders also felt a new and different pride in their agriculture since becoming involved in organic farming. The system has provided these farmers a public platform to experiment and enact their own vision of sustainable development.

In fact, they’re now local celebrities. Both Korianna and Jenaram have been featured in news reports over the past few years. They’ve been interviewed by researchers like me, recognized by visiting politicians, and featured in Facebook and WhatsApp posts by NGOs and affiliated cotton companies celebrating the successes of organic farming.

This kind of recognition motivates farmers to keep going. That’s because farmers, like all of us, perform constantly for audiences of friends, family, and institutions. A farm is a stage that lays bare experiments, successes, and failures. Receiving positive feedback from their social worlds helps people strengthen their identities and reinforces the actions they take in daily life.

Through their everyday work talking with visitors and improvising new chemical-free solutions in their fields, farmers have figured out how to make organic agriculture viable. They benefit from this work, to be sure, and calculate those benefits against the costs of farming-as-usual.

Ultimately, organic agriculture does not offer farmers a chance to grow more cotton. Instead, it offers a model of rural development that defines success through land stability, cooperative subsidies, and social celebrity—everything but growth.

Organic agriculture also offers an agrarian way of life for younger, educated generations in Telangana at a time when many young people have moved away to find work in larger cities, such as Hyderabad and Bangalore, leaving behind or even selling family land. Staff members recruited from farming communities by various organic projects in Telangana have found a way to give back to their agrarian roots while achieving a new form of rural professionalism.

It would be wrong to frame the success of these programs as either the triumph of eco-friendly clothing sales or as evidence of the inherent superiority of certified organic agriculture. Those perspectives miss the crucial efforts of NGOs and organic companies that make it easier to be a small farmer. They also hide the efforts of charismatic, opportunistic, and earnest farmers and rural professionals who take up the local cause.

These alternative agricultural systems provide a way to make farming just as desirable as the thrills of bumper yields and the security of urban work. At a time when agriculture as a way of life and a global economic system is reaching a breaking point across much of India, farmers and rural professionals who learn to value these systemic changes are building the blueprint for an alternative vision of success.