Unwrapping Operation Christmas Drop

On a balmy December morning at Andersen Air Force Base—a U.S. military installation on the tropical island of Guam—seven gargantuan C-130 Super Hercules cargo planes prepare for a mission over a vast stretch of the Pacific Ocean. The aircraft roll forward, propellers roaring, when an odd sight appears on the runway.

It’s Santa Claus!

Over the following week, aircrews in red stocking caps will deliver 210 bundles—averaging 750 pounds each—to nearly 60 Micronesian islands. As the crates drop, sage-colored parachutes burst open, like jellyfish descending toward turquoise waters. Islanders appear on shorelines, then carry the cargo to communal sites where they distribute it among local families. The parcels are stuffed with white rice, canned meats, fishing equipment, and children’s toys.

Operation Christmas Drop is an annual exercise coordinated by U.S. military personnel and allied forces. This year, U.S. troops were supported by a multilateral contingent made up of air force personnel from Japan, Australia, Canada, South Korea, and the Philippines.

The U.S. Defense Department describes this operation, which began in 1952, as “the world’s longest-running humanitarian mission.” But scratching beneath the surface, it becomes clear that the true meaning of Operation Christmas Drop isn’t about humanitarian aid.

The holiday ritual is more about militarism, exceptionalism—and what it means to be an American.

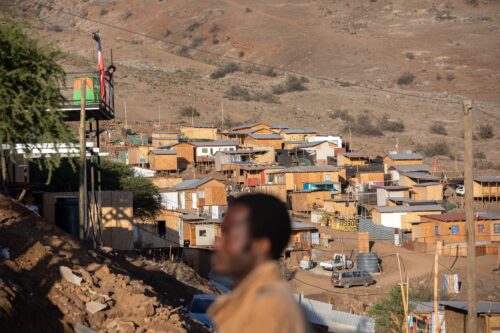

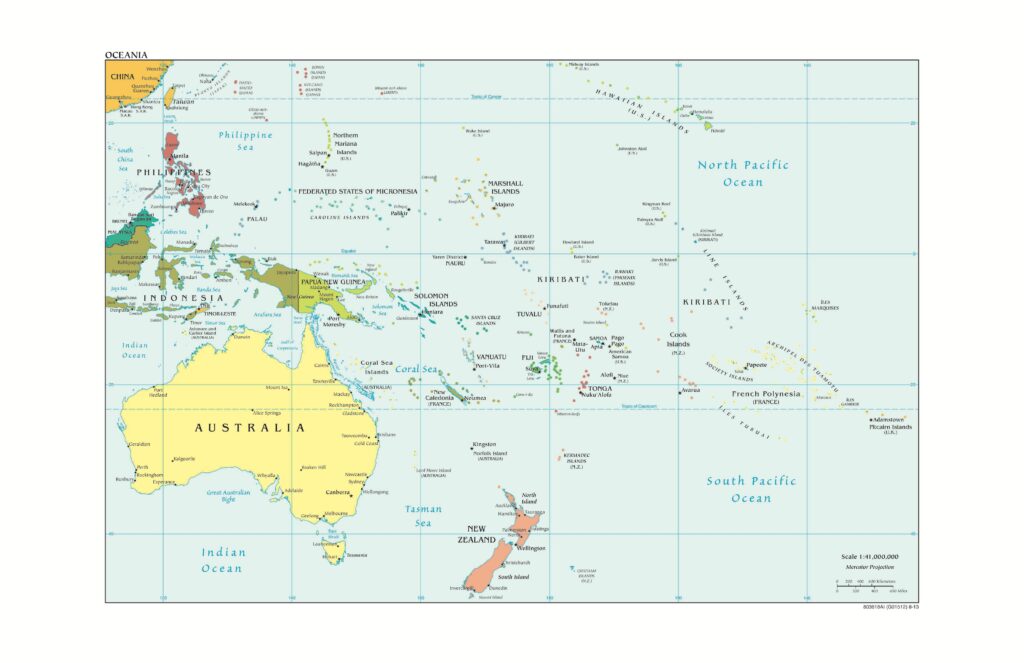

To understand Operation Christmas Drop, it helps to have some history and geography. Micronesia as a region spans hundreds of islands and includes five sovereign nations: Palau, Federated States of Micronesia (FSM), Marshall Islands, Kiribati, and Nauru. [1] [1] After World War II, Palau, FSM, and the Marshall Islands were put under a United Nations trusteeship, known as the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands (TTPI), along with Polynesian islands Kapingamarangi and Nukuoro. This arrangement effectively transformed the islands into U.S. protectorates for several decades. Today the three countries continue to receive U.S. assistance in exchange for military access to their territories through international agreements known as the Compacts of Free Association. Micronesia also includes three U.S. territories—Guam, Northern Mariana Islands, and Wake Island, a small atoll inhabited by several dozen air force personnel and civilian contractors.

The earliest Micronesians were intrepid maritime navigators who migrated from Southeast Asia more than 4,000 years ago for reasons researchers don’t fully understand. Their descendants enjoyed a hearty diet of fish, taro, yams, breadfruit, and coconuts, and developed a thriving inter-island economy. The region had, and still has, a rich cultural heritage: For instance, today eight Native languages are spoken in FSM alone.

Spanish explorers started establishing outposts in Micronesia five centuries ago. In Guam, Spanish colonization ramped up with the arrival of Jesuit missionaries in the 1660s. Within a few years, the Indigenous CHamoru (also spelled Chamorro) people began resisting the Spanish Crown’s brutal efforts to subdue and Catholicize them. Their rebellion, known today as the Spanish-Chamorro Wars, lasted for 30 years. By 1700, war and disease had killed up to 90 percent of the CHamoru population.

In 1898, the U.S. went to war with Spain, quickly defeating its forces and seizing Guam and its other colonies. Guam has remained a U.S. territory ever since, except for 31 months during World War II when Japanese troops invaded the island. U.S. military personnel and their dependents were evacuated, but Japanese troops subjected the remaining CHamoru residents to forced labor, torture, and executions. After the war, some residents viewed the U.S. not as a returning colonizer but as a liberator who freed them from a violent occupation. Other CHamoru critiqued the U.S. military’s post-“liberation” appropriation of their lands and waterways.

Today Guam is among the most militarized places on Earth. As U.S. citizens, Guamanians have access to social services but do not have political representation in Congress and cannot vote in national elections. U.S. military installations, which already cover nearly one-third of Guam’s terrain, are expanding—with damaging consequences for the island’s habitats, waters, and CHamoru ancestral sites. What is more, weapons testing in the region—which is ongoing—has introduced toxic, and radioactive, materials into local ecosystems, increasing rates of cancer and birth defects in humans and other living organisms.

In the face of these political and environmental realities, some CHamoro people demand an end to U.S. occupation of the island and continue to struggle for Guamanian independence and self-determination.

Yet pro-military sentiment in Guam (and some other parts of Micronesia) remains strong overall, partly because U.S. military dollars provide the country’s greatest revenue stream. This contributes to making Guam’s per-capita income less than that of the mainland U.S. but significantly higher than other parts of Micronesia. Many Guamanians also support the military for personal reasons: Over 15 percent are active-duty military personnel or their dependents, and another 8 percent are veterans. Guam’s per-capita enlistment rate is higher than any U.S. state.

For these and other complex reasons, many residents consider themselves beneficiaries of U.S. power rather than politically disenfranchised colonial subjects.

Operation Christmas Drop relies heavily on local Guamanian volunteers and donors. Civilians and military personnel enthusiastically participate in the main staging event. Schoolteachers organize toy collections; church groups mobilize volunteers; and families spend “Bundle Build Day” in a cavernous airplane hangar, decorating crates alongside troops who are often of Asian or Pacific Islander descent. They work under a huge banner bearing the slogan: “Love from above.”

I would never criticize these well-meaning volunteers—their commitment is admirable. But I agree with Guamanian political scientist Kenneth Gofigan Kuper and his colleagues, who describe the operation as “window-dressing for a romanticized, fossilized view of U.S. assistance. …. [that] masks nearly a century of U.S. underdevelopment in Micronesia.”

Despite good intentions, Operation Christmas Drop doesn’t substantially change islanders’ material conditions. The airlifts do not transform Micronesia in any meaningful way or address the serious threats islanders face in an era marked by climate change–induced extreme weather and rising sea levels. Given these existential threats, perhaps it’s not surprising that many islanders are opting to leave their homes; tens of thousands of residents from Micronesian islands most threatened by climate change have already migrated to larger islands or to the U.S. mainland. These migration patterns are a crucial indicator of the real struggles facing Micronesians that aren’t addressed by annual “humanitarian” missions.

According to the U.S. Air Force’s PR team, many Micronesians who receive packages are delighted to get them. A school principal from Woleai (an FSM island) noted that when “drop day” arrives, “the island just has this pure feeling of excitement … like a child just waiting to see what’s under the tree.”

Another Woleaian waxed nostalgic: “We all have our own memories. … I got my first pair of shoes in one of my first Christmas drops, and it’s something I will always remember and cherish. I wore them until I had completely outgrown them. … they were so special to me I didn’t want to let go of them.”

By these official military accounts, many islanders appreciate the gifts, even if they don’t solve long-standing economic problems.

From a critical perspective, Operation Christmas Drop can be interpreted as “humanitarian performance.” This concept, developed by theater scholar James Thompson, suggests that some nominally “humanitarian” missions are a “mix of iconic images, compassion economics,” and high drama. Thompson doesn’t deny the need for coordinated responses to catastrophes, but he is critical of efforts that disproportionately reward those who organize humanitarian aid missions rather than the recipients.

In my view, Operation Christmas Drop is a textbook case of militarized humanitarian performance. But it is also a social ritual, reinforcing deeply held values. Operation Christmas Drop embodies what many in the U.S. believe about their country’s exceptional place in the world: that it is unique in its capacity to share material abundance, practice benevolent generosity, and harness military power for humanity’s betterment.

Read on, from the SAPIENS archives: “Requiem for a War Robot.”

Ultimately, the ritual isn’t really about Micronesians; it’s about people in the U.S. Here, finally, is a military operation that makes U.S. taxpayers feel good.

Seen from this perspective, Operation Christmas Drop reproduces cherished U.S. values as a visual spectacle that is ready-made for global media distribution. Civilian volunteers, military personnel, and Micronesian islanders who receive gifts are all simultaneously subjected to what anthropologist Laura Nader calls “controlling processes”—an arrangement in which “individuals and groups are influenced and persuaded to participate in their own domination.”

With each subsequent year, Operation Christmas Drop has become more of a media spectacle. The Pentagon reaps positive publicity—locally, nationally, and globally. The U.S. military appears as an unequivocal force for good.

In late 2020, Netflix released Operation Christmas Drop, a holiday love story with Guam’s breathtaking beaches as backdrops. The rom-com is based on the real “humanitarian” mission and represents the full culmination of performative militarism. Like some other American films, it was a collaboration between the Pentagon and Hollywood, with the U.S. Defense Department providing filmmakers with free access to military planes and Andersen Air Force Base—provided that movie scripts were approved by government officials.

Many Guamanians and other Micronesians criticized Operation Christmas Drop after its debut. To some, the movie’s oversimplification of island life was offensive. For example, the film portrays CHamoru Village—a vibrant weekly celebration with food stands, live music, and locally made products—as the island’s main market. (In reality, much of Guam is heavily urbanized, with large department stores and shopping malls.)

Others considered the film to be exploitative: One scholar noted that it made Guam a “prop to someone else’s story”—a point that is consistent with broader critiques of U.S. empire in Micronesia, such as those passionately articulated by CHamoru lawyer, activist, and poet Julian Aguon.

Some had more pointed critiques. For instance, Palauan songwriter Shannon Sengebau McManus referenced the damaging consequences of decades of U.S. military intervention in Micronesia, saying, “I wish they would have told the fuller story of how there is deep trauma that our people are dealing with.” From 1946 to 1958, the U.S. military detonated 67 atomic bombs in the waters surrounding the Marshall Islands—with grave consequences for Micronesian islanders. In ignoring this history, she says, “They made [a] mockery of us as happy natives.”

Such criticisms of Operation Christmas Drop may someday develop into a broader movement against the “humanitarian” operation itself. As the U.S. military transforms Micronesia into a beachhead and frontline in a prospective war with China, discontent among residents may be reaching a tipping point.

Time will tell whether the growing number of activists seeking the demilitarization of Guam and greater Micronesia will eventually become a rising chorus of voices challenging U.S. hegemony in this captivating, but ecologically fragile, expanse of the Western Pacific.