Fishing in the Shadow of Oil

We cut the engine as the sun was coming up, letting our small boat drift toward our target: a massive ship carrying liquified natural gas that was anchored a few miles offshore. My friend Abu Abdullah (a pseudonym) had brought me out that morning with his usual fishing crew: his brother, one of his sons, and a cousin. As the oil tanker loomed overhead, dwarfing our small skiff, we idly chatted as we brought in ‘ouma and sima (Indian oil sardine and scad in Gulf Arabic) by the hundreds. [1] [1] Indian oil sardines are named not for petroleum but for their oily flesh.

In the warm waters of the Persian Gulf and Gulf of Oman, the extraction of fish and oil are entwined in profound ways. For my dissertation, I’ve been researching the extraction of natural resources—fish, pearls, sponges, and oil—from these waters.

That day, I was tagging along (and trying not to get in the way) as Abu Abdullah and his crew sought to fill the boat with enough baitfish to lure in the more lucrative catch: tuna. The smaller fish have learned to shoal in the shadows of large ships to avoid predation—but fishermen have learned to find them there by venturing (often unauthorized) into the cool waters below offshore rigs and oil tankers. The tuna these men catch with the baitfish and sell at the local market serves as their primary source of income.

Before the petroleum boom of the 1960s, small-scale fishing was the largest and most important industry in the region. After the first wells were drilled, however, traditional fisheries were quickly eclipsed in importance by the global fossil fuel industry. Fishermen were met with seas darkened by oil and choked with the industrial machinery of extraction.

To fish in this region today is to fish, literally and metaphorically, in the shadow of fossil fuel.

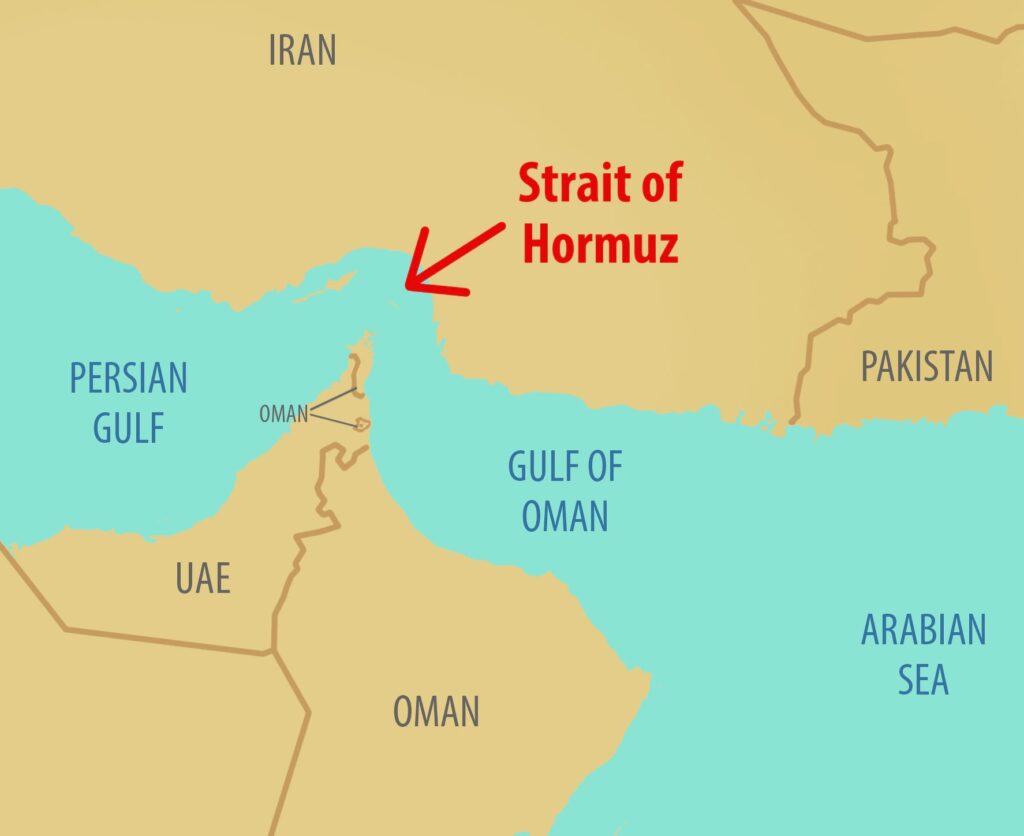

As a result of oil’s economic primacy in the region, the seascape around the Arabian Peninsula has been remade in the image of petrocapitalism. Oil rigs sit atop pearl beds that divers visited in living memory. Fishing boats must carefully weave between tankers clogging the waters near the Strait of Hormuz, where 20 percent of the world’s oil flows through each day. The rigs, tankers, terminals, and ports that circulate this oil are highly securitized spaces, which sometimes makes fishing around them a risky endeavor.

Even the price of fish is tied to the price of oil. As one Omani fisherman on TikTok noted last year, “The main reason for the soaring cost of tuna is petrol.”

Fossil fuel also looms over the region’s fisheries in other, less apparent ways. That day on the boat, I noticed how the byproducts of the oil industry saturate the work of fishing. Our small vessel was cluttered with commodities downstream from oil—nylon lines, plastic buckets, polystyrene buoys and coolers, squid-shaped lures made from rubbery plastisol—all strewn upon the fiberglass-reinforced plastic skiff. It is perhaps because of this saturation that lost and abandoned fishing gear accounts for the majority of ocean plastic worldwide, including the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

But fishermen in the Gulf region also make creative use of other byproducts of petroleum, turning objects created not just by but for the oil industry into gear. Fishermen here have always made use of whatever is at hand; previously, it was date palms and coconut coir. But since the dawn of the oil era, the materials at hand are that industry’s castoffs: plastic, nylon, Styrofoam, polyester. Across the shores of Oman and the United Arab Emirates, one frequently sees plastic oil drums (khazānāt, Arabic for “tanks”) that have been refashioned into fish traps for catching ‘ouma, the bait tuna love most because of its pungent smell.

Standing on the deck of the skiff that morning, with an oil tanker above and oil sardines below, and with oil-derived gear at our feet, we were participants in a peculiar gathering that connected disparate rhythms, things, species, and people together.

Anthropologists and other social theorists sometimes refer to these gatherings as “assemblages.” [2] [2] See anthropologist Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing’s work on mushrooms, which merges philosophical understandings of assemblages with ecologists’ use of the concept. The rhythms of ships coming in and out of port, as well as the fate of their contents (as raw material, refined fuel, or plastic), are determined by the demands of capital. The rhythm of the sardines shoaling beneath them, meanwhile, are determined by biology, the ocean’s tides, and the earth’s seasons. Anthropologist Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing has argued that assemblages like this where “nature” and “culture” converge are unique vantage points to trace the political and economic contours of our current global era and to reveal “potential histories in the making.”

One strength of assemblage thinking is that it reframes how power dynamics work, shifting our focus on who (or what) is able to shape how events unfold. As climate catastrophes increase in intensity and frequency due to anthropogenic climate change, it can feel like the fate of the planet is predestined for total ruination. Oil’s grip on the future feels unbreakable. But it’s possible to take a longer view and widen the lens. By including what happens at the “unruly edges,” in Tsing’s words, of oil extraction, even the all-powerful and securitized fossil fuel industry looks like one mere player in a story that includes other creatures and ways of life.

And in the shadows of oil, those longer histories are still unfolding.

Like the TikToker mentioned earlier, fishermen notice the many juxtapositions and convergences between the fishing and oil industries, and are keen observers and critics of the changes wrought by fossil fuel extraction.

Even young fishermen recall the time before oil, if only through stories. They know that further despoliation of the marine environment from discarded plastics, oil spills, and industrial pollution endangers the sea’s fragile ecology and threatens their livelihood.

But they also know that the boats, nets, and lines they rely on are derivative of petroleum. As such, they tend to reuse and refashion as much as they can.

The history, actions, and perspectives of Gulf fishermen are a crucial reminder that oil is fairly “new,” finite, and not invulnerable. Fishermen’s bold and sometimes irreverent tactics of carving out a living in the shadows of oil tankers points to cracks in the fossil fuel industry’s powerful veneer of untouchability and permanence.

And even if their own refashioning of the oil industry’s discards is borne out of necessity, it still reveals an important insight: The unique durability of petrochemicals can act as a double-edged sword. The same fossil fuel–derived plastics and other materials plaguing the marine environment also belie oil’s redundancy and excess. If items can be used over and over ad infinitum, the need to extract more oil to produce new products lessens, at least for fishermen.

Back on the boat, as the sun crept overhead, we pushed off the gas carrier’s immense hull to head another 50 miles offshore to where the tuna were running. While we readied the lines to use the bait we had just caught, a Filipino seafarer shouted down to us from the tanker. He asked in English for a lead weight so that he, too, could fish in the cool waters below.

“What does he want?” Abu Abdullah asked me in Arabic. When I told him, Abu Abdullah untied one of the weights from his nylon line and threw it at the enormous tanker. It bounced off the domed tank, and the seafarer plucked it off the deck, held it aloft, and disappeared to ready his own line to fish in the shadow of his own massive ship.

To the seafarer, and to us, the fossil fuel industry was but a backdrop, casting a shadow onto worlds saturated by but not erased by oil. A shadow that we would fish in together.