Native American Children’s Historic Forced Assimilation

In May 2018, U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced that the government would begin to separate children from their families who had crossed from Mexico into the United States. More than 5,000 children were torn from their relatives. Tragically, this is not the first time the U.S. government has systematically and forcibly removed children from their loved ones.

In 1890, the U.S. government ended open warfare against Native American tribes, which had begun in the 17th century and intensified through the 19th century. The population of Native peoples—once in the millions—had plummeted to around 250,000. Many of these politically and militarily defeated communities were confined to reservations that occupied a fraction of their traditional homelands. What to do with these newly confined peoples?

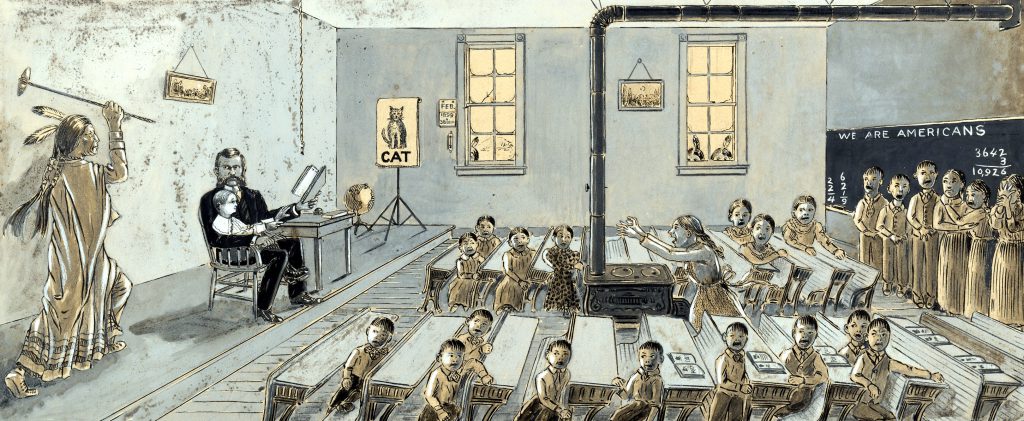

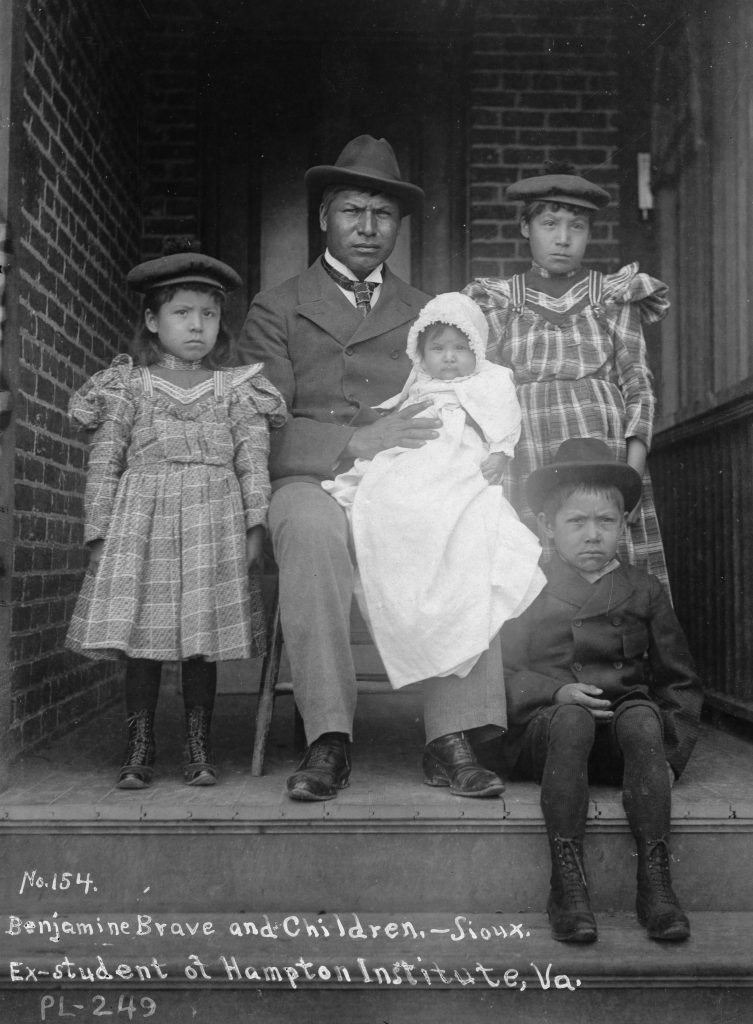

The goal became assimilation: to transform Native Americans into “good Christian citizens.” As one school founder said at the time, “Kill the Indian in him and save the man.” This was attempted by breaking up reservations and outlawing religious practices. However, many felt that Native adults would likely never change. Real change could only come by focusing efforts on their children.

In the most extreme cases, law enforcement took children at gunpoint.

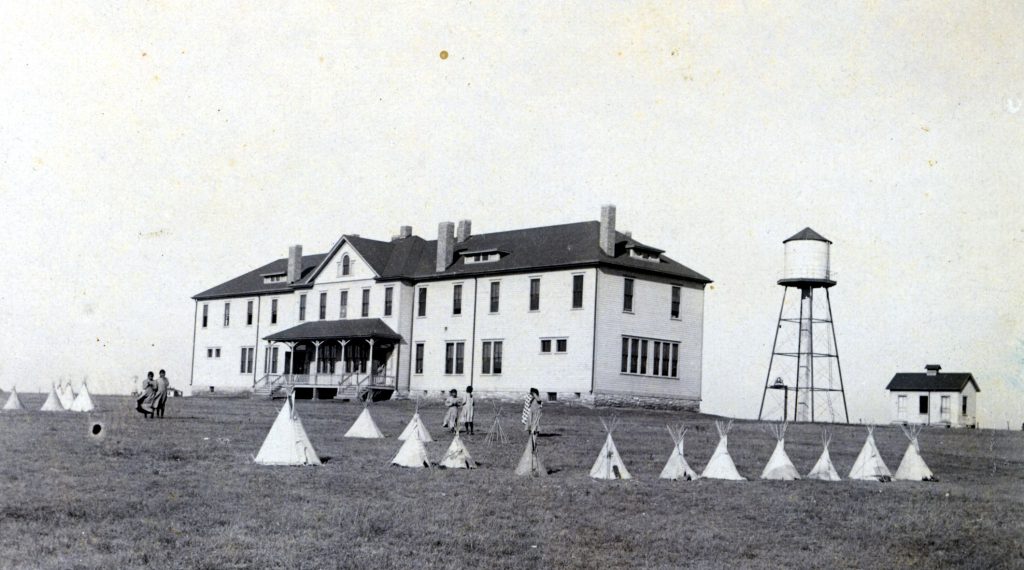

Schools had been started for Native students since the founding of the United States. However, the role of schools in assimilating children now took on new urgency. By 1900, 307 boarding schools and day schools had opened across the country, educating more than 26,000 Native students.

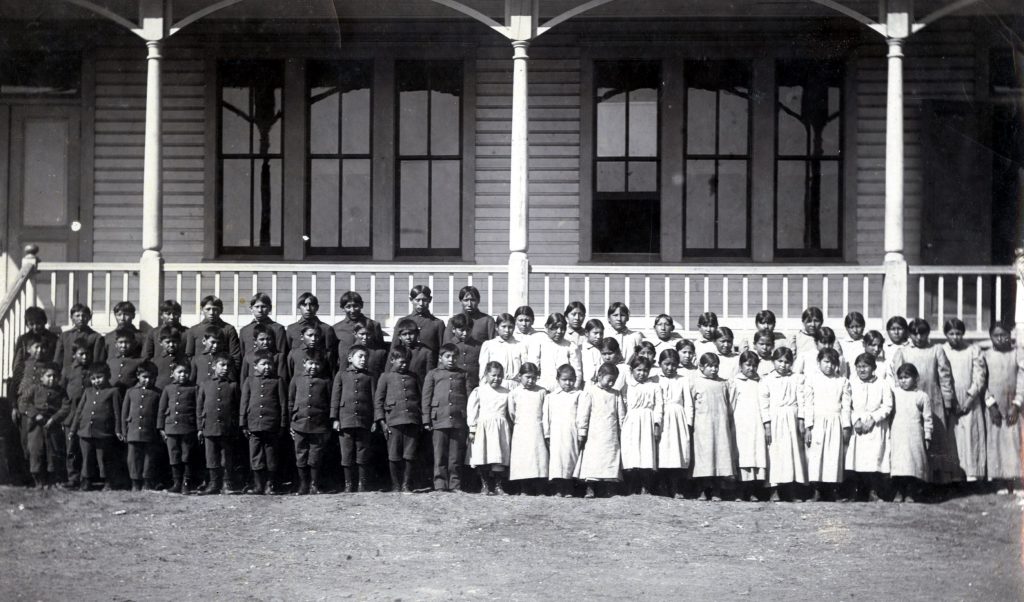

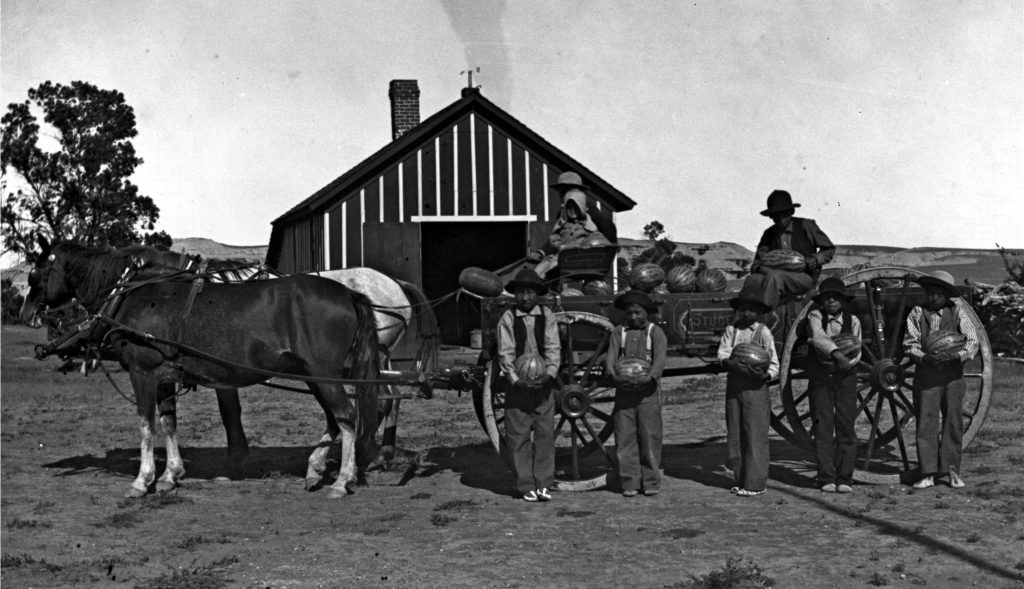

While some parents embraced the opportunity for their children to learn English and other skills, many more saw that these institutions were not really schools at all. Children were forced to cut their hair, wear uniforms, speak English, perform manual labor, suffer corporal punishment, and offer Christian prayers. At boarding schools, children had to endure a new life without any family support.

Parents who resisted sending their children to these schools were often severely punished. Government officials withheld food rations that families depended on. Fathers were sent to prison. In the most extreme cases, law enforcement took children at gunpoint.

To implement this assimilationist policy, the U.S. government needed teachers to cut children’s hair and issue uniforms, try to force them to forget their languages, and instruct boys in farming and girls in sewing. Jesse H. Bratley was one such teacher.

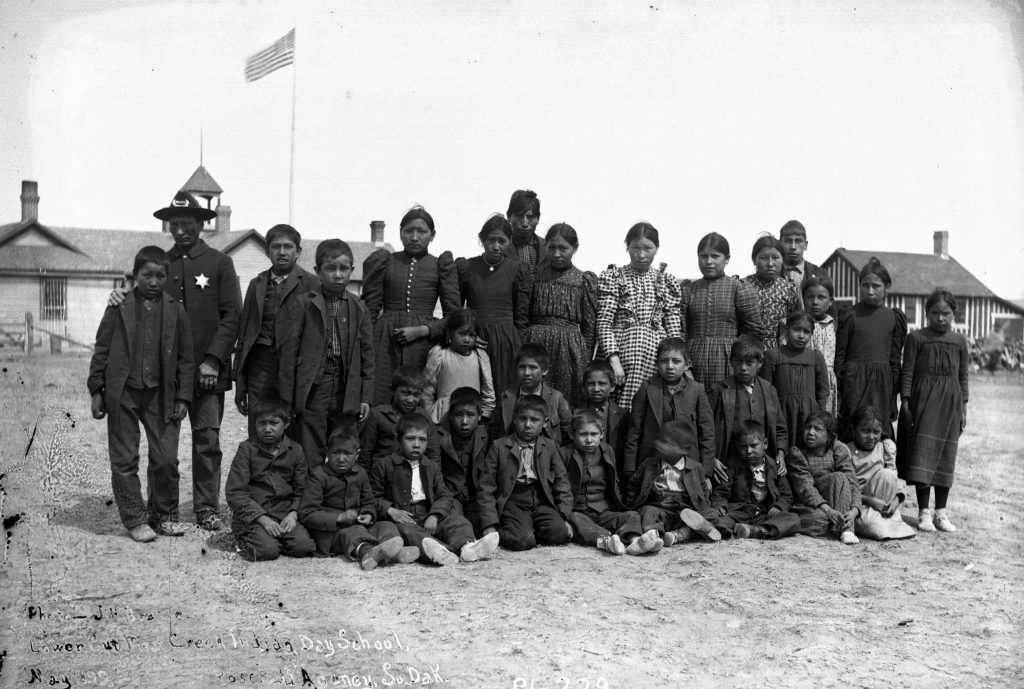

Between 1893 and 1903, Bratley worked in schools on five reservations. He also documented Native people and places through almost 500 photographs. Bratley and his images defy easy categorization. He admitted that, as a boy, he “despised” Native Americans. As a teacher, it was his job to help annihilate Indigenous peoples’ cultural identities. Yet he became enthralled by these cultures, observing ceremonies and encouraging some traditional practices. He cherished his time living among Native people and formed real friendships. Yet he had numerous conflicts with his students and their families, and there is no evidence that he advocated for Native peoples’ rights or even acknowledged the validity of their ways of life.

In our new book titled Objects of Survivance: A Material History of the American Indian School Experience, we have interpreted and analyzed Bratley’s photographs, offering an unprecedented glimpse into what the U.S. policy of separation and education wrought more than a century ago. In this photo essay, we offer a small selection of images that capture the cruelty of the U.S. government’s education system for Native Americans. They demonstrate one man’s attempt to make sense of his place in that historical moment and his new life amid Native peoples.

Even more, they show how Native peoples both persisted through and resisted the U.S. government’s commitment to erase their cultures. This is a story of loss, but it is also a story of survival.

![While teaching on the Hopi Reservation in Arizona, Bratley likely posed this image of his student Ruth Honavi having her hair made up in the butterfly style. Hopi culture likens women to gentle, life-giving butterflies, and this tradition continues today for girls participating in ceremonies. Bratley once wrote that long hair was “a part of [Indigenous peoples’] very being and religion,” yet he encouraged cutting boys’ hair.](https://www.sapiens.org/app/uploads/2020/03/Figure-09-BR61-233-1024x700.jpg)