Mourning Kin After the End of Cannibalism

Excerpted from Paletó and Me: Memories of My Indigenous Father by Aparecida Vilaça, published by Stanford University Press, © 2021 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University. All rights reserved.

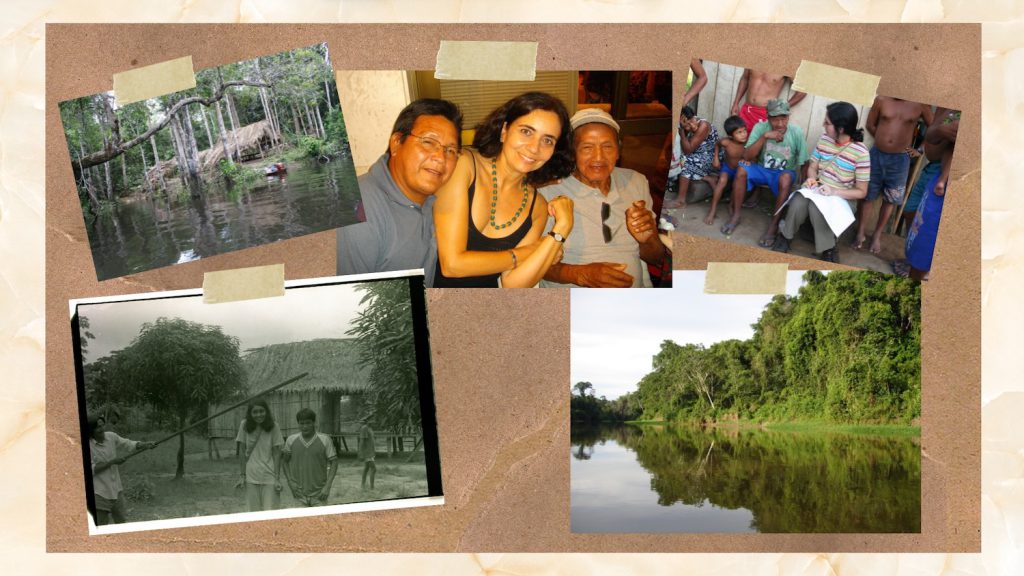

Author’s note: I started writing Paletó and Me on January 17, 2017, when I was informed through a WhatsApp message of the death of Paletó, an Indigenous man of the Wari’ people of Rondônia, Brazil, who had adopted me as a daughter. I called him Dad. I met him in 1986 in the Rio Negro-Ocaia village 20 years after his people had their first peaceful contact with White people.

At first, he and I couldn’t communicate directly, as I didn’t speak his language. But Paletó didn’t give up teaching me about the Wari’ and their ways of life; we relied on gestures and translations by his son Abrão. Paletó, then in his 50s, was considered a sage, a connoisseur of myths and rituals. He was also known for his sharp intelligence and good humor, characteristics he maintained throughout his life, even after experiencing traumatic events, including the massacre of his family in the mid-1950s by armed men sent by rubber tappers who coveted his lands.

Over time, I learned Paletó’s language, and we became closer and closer. My grief at the loss of this man who had changed my life and made me the anthropologist I am today plunged me into writing. In the excerpt below, frustrated at not being able to attend his funeral in person, I recall what I learned from Paletó about how his people grieved the loss of kin in the past. Until their encounters with Christian missionaries in the 1960s, Paletó’s community had practiced mortuary cannibalism—eating the bodies of their dead. Nowadays, they bury their dead, as they did with Paletó.

Paletó died at the hospital in Guajará-Mirim, the closest city to his village in southwestern Amazonia. His body was first carried to the city port and then transported by boat to his village to be buried.

I was told that the voadeira (a small boat with a 40-horsepower outboard motor) left the port at 10:30 a.m., the sun already high in the sky. I imagine the journey, the stops in the various villages en route for relatives to be able to see the deceased, the dramatic arrival at the destination with a crowd of people waiting and crying, including three of Paletó’s children, Abrão, Davi, and Main, who had decided not to go to the hospital. They will spend the night crying, now with the casket open and the body able to be touched and embraced. Perhaps they will take the body out of the coffin and lay it on the floor. Then someone will lie down and slide themselves under the body, and others will follow, each lying under the previous person, forming a human pile that is maintained until the last person faints and is removed. They want the smells, the liquids, everything that the body can still offer them.

In the past, when an important man died, who had himself taken part in many festivals, the body would be carried on the shoulders of a living man and offered sweetcorn chicha, a fermented, alcoholic drink, just like guests during a festival. Soon after, his double would arrive in the subaquatic world of the dead, where he would drink more chicha, offered by a man with big testicles called Towira Towira (“Testicle Testicle”). Full of chicha, the double would vomit and then be taken to the men’s house for a period of seclusion, in the same way as a warrior after a successful war expedition. And indeed, for the Wari’, the dead man had turned into a warrior, hence his young and vigorous appearance—the same as the double of Paletó who had appeared in a dream I had the night before.

In the past, the dead were not buried as Paletó will be in his coffin in the cemetery upriver. The burial site was established by the U.S. evangelical missionaries of the New Tribes Mission, who arrived in the region of the Negro River in 1961 to help in what was euphemistically referred to as the “pacification” of the Wari’. Missionaries remain in some of the villages to this day. In the past, Paletó’s body would have been free of the coffin, placed on a stilt palm platform and held by kin, while other people prepared the fire that would roast it. Two or three days would pass until everyone arrived from their own village to see the body still intact, to hug it, and to place themselves under it. Some of the closest kin, driven to despair by the death and with everyone around them distracted, would suddenly throw themselves on the fire, wanting to join the loved one in the underwater world where all people eventually go. Usually, they were rescued and survived; some, however, died.

I recall Paletó often dramatizing for me the various movements related to the dead person and to those mourning the death so that I could understand the ceremony and record and film the stages of its enactment. On one occasion, Paletó, Abrão, and I were in the living room of my apartment in Rio de Janeiro. Two chairs, joined by broom handles, functioned as the funeral grill. A wadded newspaper underneath was the bonfire. A cheap plastic doll with detachable legs, arms, and head, bought by us at a downtown store, was the dead person.

Paletó insisted that I take an active part, instead of only filming, so I could learn the details of the ritual properly. He demonstrated the roles of the two groups involved in the funeral: As kin to the deceased, I should cry and walk around crouching and singing (You see? I had even rehearsed the song that I was unable to sing at the necessary moment!) and asking non-kin, one by one, to eat the deceased. When performing the role of non-kin, he taught me to take the roasted flesh, which was divided into small pieces (substituted there by bread) and, using chopsticks, place each piece in my mouth delicately, showing gentleness to the kin of the dead person who had asked me to make the body disappear by eating it.

The dead person’s kin asked others to eat the body to complete its disappearance, as its sight provoked intense longing and sadness. The kin themselves, overwhelmed by the physical presence of the deceased, which left the person still alive in their memory, were incapable of doing so. But it was not just the body’s disappearance that the Wari’ sought when asking that others eat pieces of the flesh of their dead kin; simply burning the corpse would have achieved the same objective. By eating the body, non-kin showed to the mourners that a corpse is no longer a person and thus can be eaten. Hence, they initiated the lengthy process of mourning on the part of kin, which would culminate in their own eventual capacity to adopt the perspective of non-kin, the eaters, eliminating from their memory the human embodiment of the deceased.

The dead person’s kin asked others to eat the body to complete its disappearance, as its sight provoked intense longing and sadness.

In our enactment, Abrão and I took turns performing the roles of those who cry and those who eat, and also, in this case, those who film. Abrão quickly learned to handle the camera, and the stability of the image was only lost when the three of us fell into fits of laughter, one time right at the moment when Paletó tried to throw himself in the fire-newspaper and Abrão needed to rescue him.

Paletó told me more than once that he found it difficult to eat the flesh of people, which usually had a very strong smell, better described as a stench. He told me how a dead woman’s kin once asked him, while still a young man, to eat her flesh. Paletó said that he tried, eating a small amount, but soon afterward quietly sneaked away to vomit. I assumed, since it was the corpse of an adult woman, it must have been far along in the process of decay, as they would have waited days for the arrival of all her kin before cutting up and roasting the body.

Paletó spoke a lot about this during our filming and, in one of the scenes where I feigned eating the flesh of the dead doll, he made me turn aside and pretend to vomit. He explained that this should never be done in front of the deceased’s kin, as it would be considered indelicate. But what was really indelicate, he added, was eating the flesh with the same relish that one eats game. Immediately after death, the corpse is still not animal and, though this is what it will turn into later, it was important to respect the perspective of the kin, who still saw the body as a person, as though alive, in the same way that I now see Paletó in my memories. The risk of such a faux pas—eating flesh with a display of pleasure—was greater when the flesh was roasted before it became rotten, as in the case of a dead child, whose wake was shorter.

Read more, from the archives: “An Excavation of the COVID-19 Pandemic”

In the past, everything was eaten. The body was consumed entirely, leaving nothing of the dead person’s flesh. If by chance something was left, it was thrown on the fire along with the bones, all to be burned and thus to vanish. All the deceased’s belongings were also burned, as well as their house, the plants of their garden, and even the tree trunks where the person had sat along the forest paths. The Wari’ called this act of destruction “sweeping”—sweeping up everything of the dead person, which included shaving off the hair of close kin, frequently touched fondly by the deceased.

Paletó once told me that were I to die, he would cry profusely. He would rip up the clothes that I had given him and throw them on the fire. I think about what they will do today with Paletó’s belongings, among them his suitcase, always with him, his clothes, the red scarf I gave him some years ago, blankets, and shorts. Will they destroy them? Will they give them away? Or sell them to someone, as they tend to do today with more durable items like radios or televisions? To’o Xak Wa, his wife, once told me that in the past this was never an issue, since the only durable items were clay pots, which would be smashed and thrown on the fire that roasted the deceased.

This excerpt has been edited slightly for style and length.