The Vibrant Worlds of Batuan Paintings in Bali

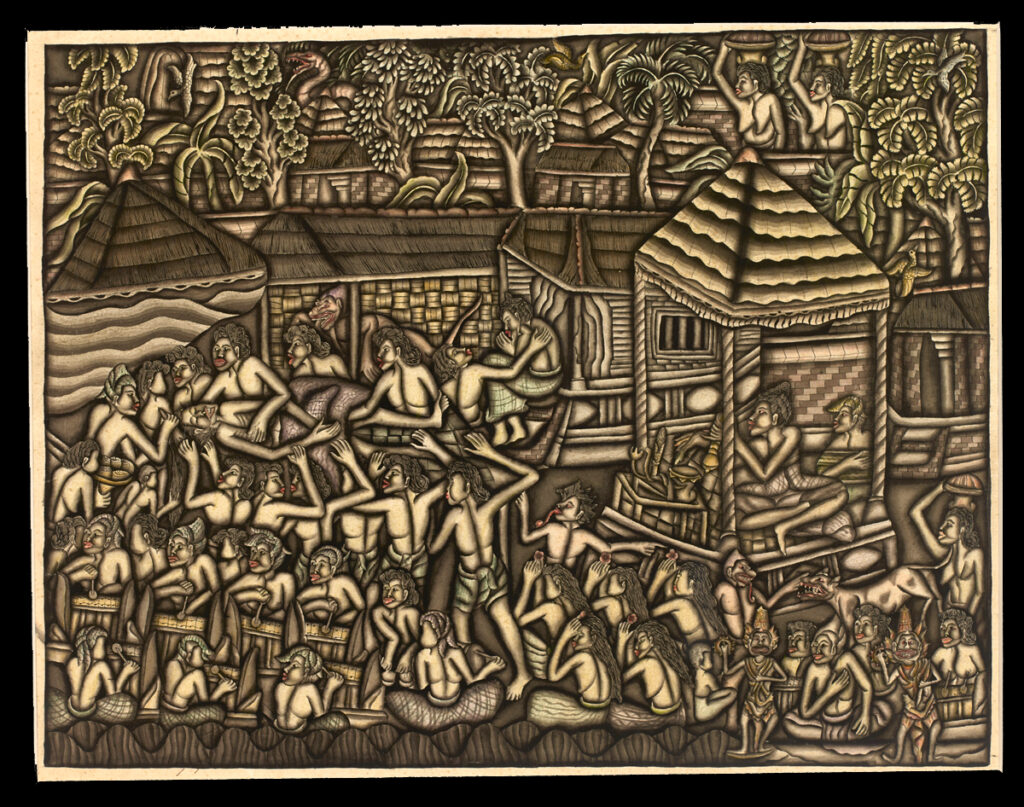

In his peaceful home studio in Pekandalan, Bali, Indonesia, I Made Tubuh swirls his brush into a small bowl of black ink. With short, delicate strokes, the painter outlines a detailed figure. When the painting is done, it will be brought to Ubud, an artistic and spiritual epicenter, and displayed at one of the many galleries in the small city. Tubuh’s work will join canvases by fellow Balinese artists, hung on the wall and stacked by the dozens, depicting local performers, landscapes, village scenes, figures of myth and legend, and more.

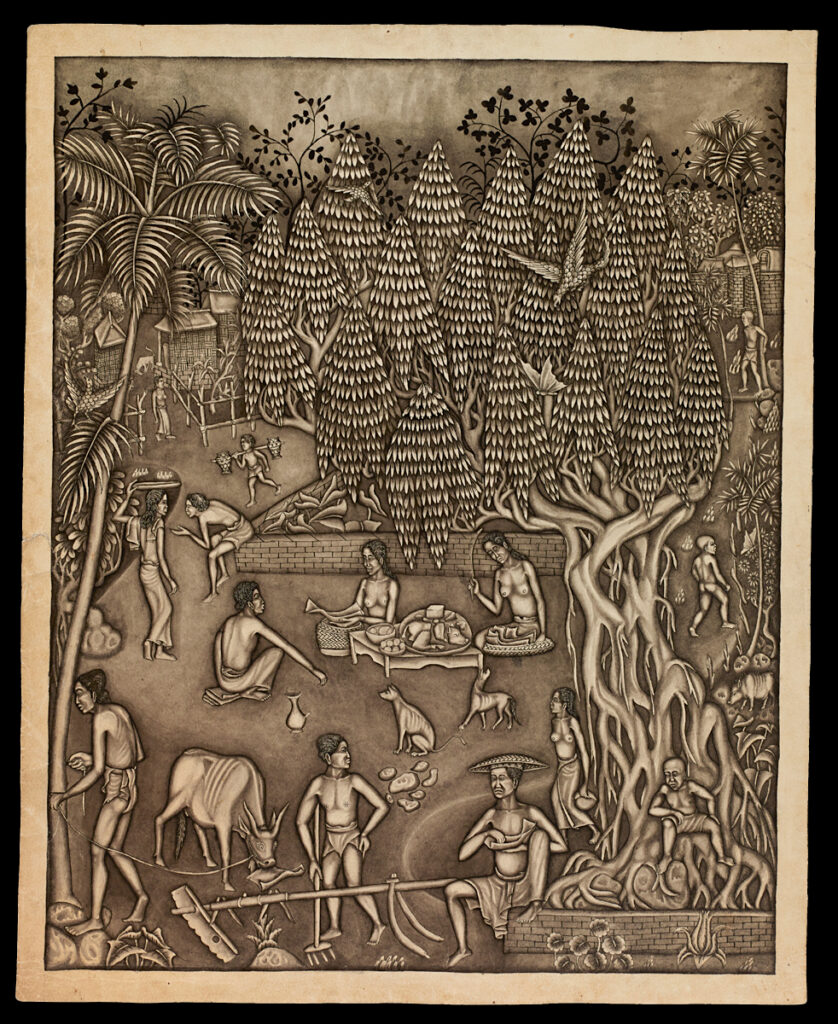

The thriving art scene in Bali today has some surprising influences: Like Tubuh, many artists from Batuan, a village near Ubud, have ties to noted anthropologists Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson. The pair saw art as a reflection of how people from a particular culture thought and felt. So, during their fieldwork in Bali in the 1930s, Mead and Bateson commissioned drawings and paintings from Batuan and the surrounding area. They invited artists to create psychological and cultural content based on folklore, dreams, fantasies, and daily experiences.

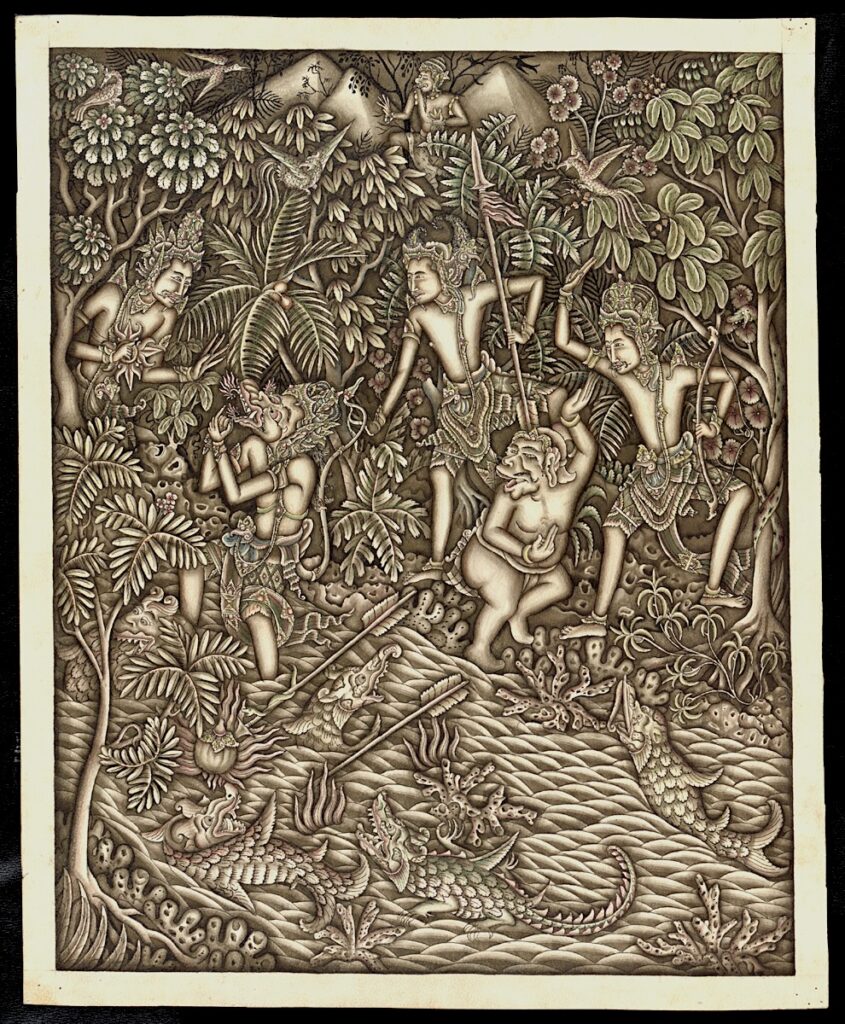

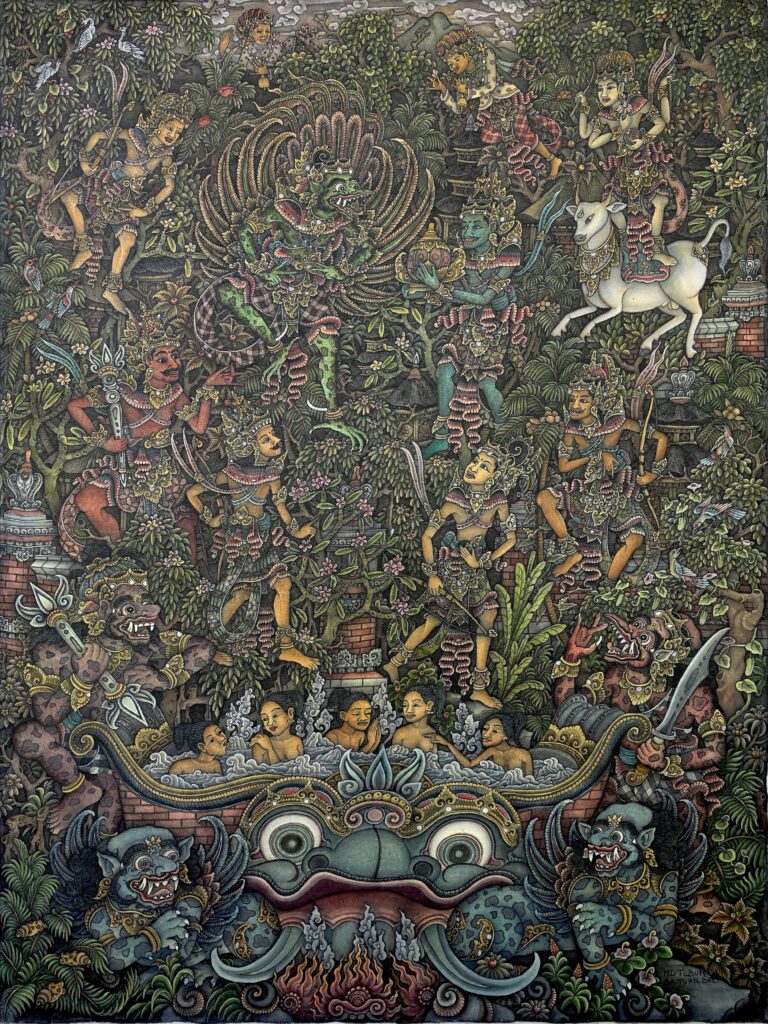

Balinese artists didn’t typically portray that kind of subject matter. Painting at that time mainly centered on religious, communal, and mythical themes and, in many cases, was made for palaces and temples. But the artists were willing to experiment.

Mead and Bateson ultimately commissioned and collected more than 1,200 works by over 80 individuals, including novices and recognized masters in genres such as mask-making, shadow puppetry, and costumery. Their Balinese research assistant, I Madé Kalér, took notes on the works and interviewed some of the artists about their lives. This data, along with the paintings, informed Mead and Bateson’s 1942 ethnographic book, Balinese Character.

To learn more about I Madé Kalér, read on from our archives: “Unsung Native Collaborators in Anthropology.”

The artworks were then archived at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. They remained unseen for decades, until anthropologist Hildred Geertz took renewed interest in the collection. Geertz began researching and writing on how economic development and tourism had changed Balinese art forms over the decades. [1] [1] Many of the paintings in the collection compiled by Bateson and Mead can now be viewed at The Virtual Museum of Balinese Painting, a Balinese art archive by Southeast Asian historian Adrian Vickers and Indonesian studies scholar Peter Worsley and colleagues. Note: Titles for artworks in the collection were added by Geertz.

Mead and Bateson’s time in Bali, it turned out, had dovetailed with an influx of cultural tourists, some of whom settled on the island. Bali had resisted Dutch occupation for much longer than other parts of Indonesia, but by 1908, the island was under Dutch rule. Dutch colonists—struck by the intricate beauty of Balinese rituals, offerings, and performances—imagined the island as a “living museum.”

Intercultural artist collectives formed during this period. Such groups were not free of exploitative colonialist dynamics; like the settler colonists, foreign artists often exoticized and commodified Balinese culture. But these often-fraught exchanges ushered in a century of creative experimentation on both sides. For expatriate artists from Europe and North America, exposure to local arts offered an opportunity to break with their conventions. Meanwhile, the introduction of new art materials and approaches from Euro-American traditions, combined with the eager anthropologist buyers ready to pay a good price for so many works, led Balinese artists to pursue a novel style of painting.

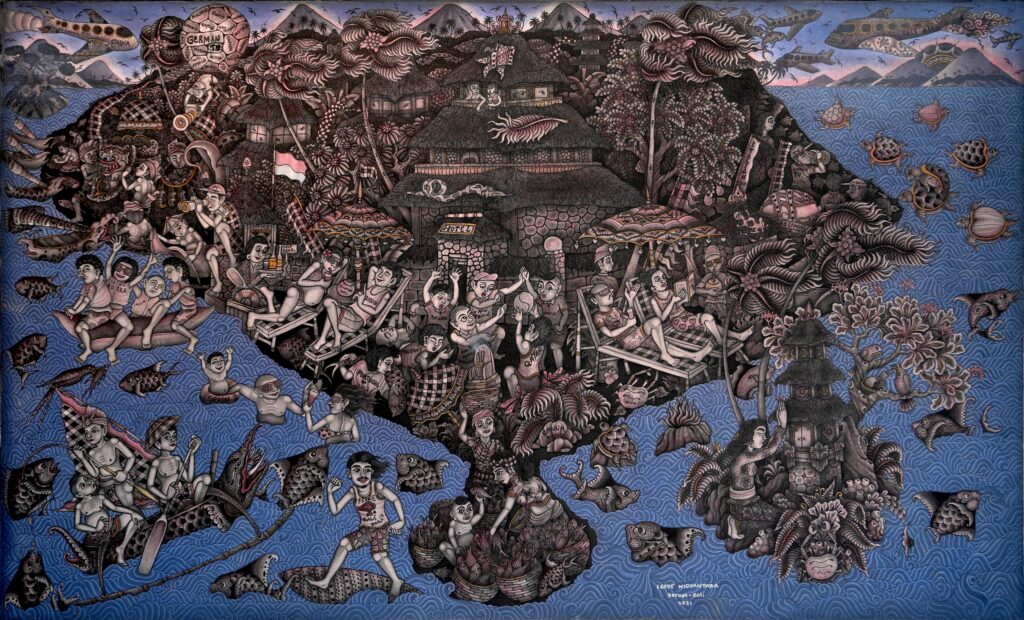

The genre of Batuan contemporary painting that emerged in the early 20th century depicted Balinese culture for an international audience. Yet it remained deeply rooted in local life and personal expression. The artists of this original style balanced innovation with attention to enduring cultural concerns. They were particularly interested in exploring the invisible powers that threaten to disturb and destabilize human activity, and people’s attempts to uphold individual and collective harmony through aesthetic ritual practice. The elements of this genre remain evident in many Batuan paintings today.

A core group of about 20 skilled and prolific painters joined the intercultural artist collectives and were represented in Mead and Bateson’s collection. These included I Made Jata, I Ketut Tombelos, and Ida Bagus Ketut Diding, who continued to make work combining Balinese and Euro-American themes and approaches. Over the following decades, they saw commercial success and became leaders, teachers, and mentors in the Batuan art world.

Tubuh, who came from this tradition, has seen his paintings purchased by visitors from all over the world and sold at international art auctions. His style of painting has become a valued part of Batuan cultural heritage—and a pillar in Bali’s tourism industry.

In a recent effort to bring this history, archive, and legacy of Batuan painting to a wider audience, anthropologist and co-author Robert Lemelson partnered with curator Rebecca Hall to create the 2022 exhibition Bali: Agency and Power in Southeast Asia for the University of Southern California Pacific Asia Museum. An affiliated multimodal website, Batuan Interactive, seeks to further amplify Balinese voices in telling the story of the collection Bateson and Mead made, and highlight Balinese efforts to keep this tradition of painting alive.