The Half of the World That Doesn’t Make Out

When the South African Thonga peoples first saw Europeans kissing in 1890, their reaction was disgust at such gross behavior. The same thing happened 100 years later for the Mehinaku of Amazonia. In Melanesia, the Trobriand Islanders are said to have regarded kissing as “a rather insipid and silly form of amusement.”

To go by today’s popular Western culture you would think the romantic kiss is a pleasurable human universal. Many people, including evolutionary and social psychologists, have suggested as much. It seems a natural conclusion: Even chimpanzees and bonobos kiss—including with open mouths and tongues. But clearly not everyone kisses. In fact, in our recent study, published in July 2015, less than half of the cultures we sampled engage in the romantic kiss.

We looked at 168 cultures and found couples kissing in only 46 percent of them. Societies with distinct social classes are usually kissers; societies with fewer or no social classes, like hunter-gatherer communities, are usually not. For some, kissing seems unpleasant, unclean, or just plain weird. Kissing is clearly a culturally variable display of affection.

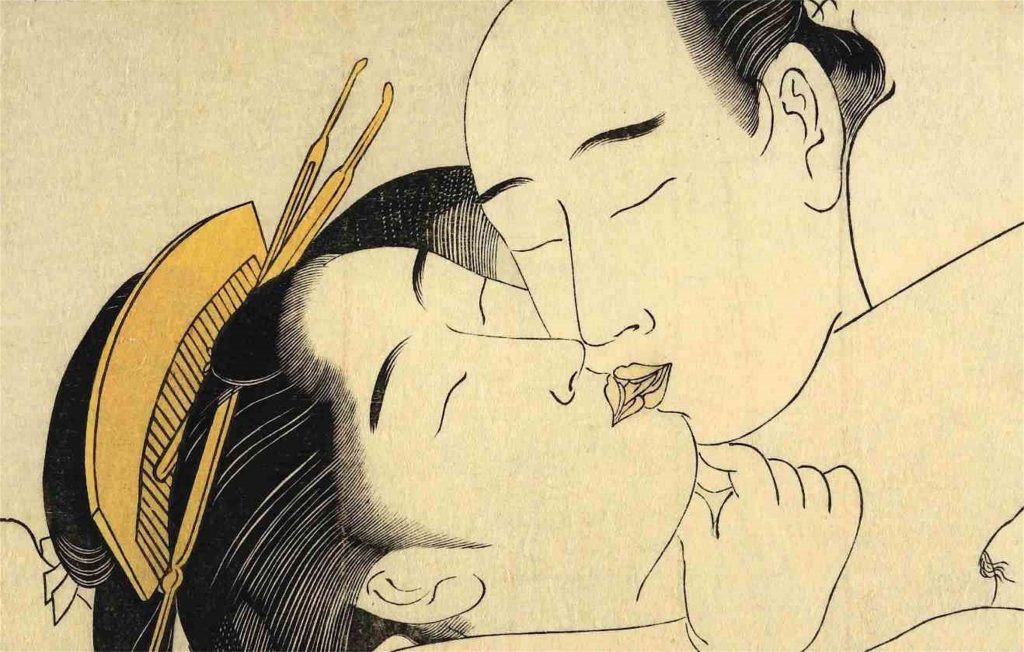

No one knows the exact origins of the romantic kiss. Some say it evolved to help test potential partners’ health through taste, their genetic compatibility through the smell of their immune system, or their romantic interest and sexual compatibility. Alternatively, it might have evolved from “kiss feeding”—the practice of a mother chewing up food and pushing it into her infant’s mouth with her tongue. The earliest known reference to kissing is in the Vedas, a 3,500-year-old Sanskrit scripture. Many classical societies, including the Romans, were passionate about kissing.

At least 90 percent of today’s cultures have kissing of one type or another, but the majority of it is parents kissing their children. Far less is known about patterns of who kisses romantically and who does not, and why.

Our study was the first to map out the culture of romantic kissing around the world (one other, a 1951 study, looked at a tiny sample of 13 societies, of which only five had romantic kissing). We trawled through databases of ethnographic studies and surveyed ethnographers to come up with a dataset of 168 cultures spread across the globe, with most studies done in the early 20th century (we included just one of 34 ethnic groups in the United States—the Amish people, who do, as it happens, kiss—to avoid swamping the data with U.S. results). Since some studies might not have mentioned kissing just because the ethnographer wasn’t interested in it, we looked particularly for studies that mentioned parent-child kissing but didn’t mention couples kissing. Some intriguing patterns emerged.

First, most egalitarian foraging communities don’t kiss sexually. Since hunter-gatherer tribes may serve as a window into societies of the distant past, it is reasonable to assume that romantic kissing has emerged recently in human history. A notable exception is that nine of the 11 such communities in the circum-Arctic region (the Inuit peoples, for example) do engage in romantic kissing. One explanation for this is that humans like to touch. So it is possible that when confronted with people dressed head-to-toe in thick furs, the face and the lips become the only, or at least the most obvious, parts of the body available to explore. In tropical regions, less clothing is worn, exposing more of the body and potentially making the face less important. In any case, the fact that these cultures don’t kiss romantically does not mean they are prudish: The Mehinaku, who live in Brazil, for example, are known to nibble at eyebrows during sex.

Second, there is a strong link between kissing and social complexity. It makes sense that romantic kissing might have come about with the growth of leisure time. Kissing is delayed eroticism; it’s a tease. It’s also possible that as societies stratify into different layers and social classes, their behavior stratifies too. If you have aristocracy and peasants, you might also have polite cheek kissing and more-intimate mouth-to-mouth for different classes or circumstances.

More industrial, modern societies might also have better oral hygiene, making kissing a more pleasing activity for some than for others. One argument against this speculation, though, is that hunter-gatherers, who eat very few carbohydrates, may have fewer dental cavities than bread-eating Europeans, yet most hunter-gatherers have not evolved romantic kissing.

To claim something is a universal, it should be in all societies. Romantic kissing is clearly not. Now the next question to answer is why.

Correction: February 15, 2016

An earlier version of this article mischaracterized one of the cultures discussed. The Mehinaku are not hunters and gatherers, but depend on fishing and slash-and-burn horticulture.