Home-Carrying—A Repatriation Trip to Vanuatu 100 Years in the Making

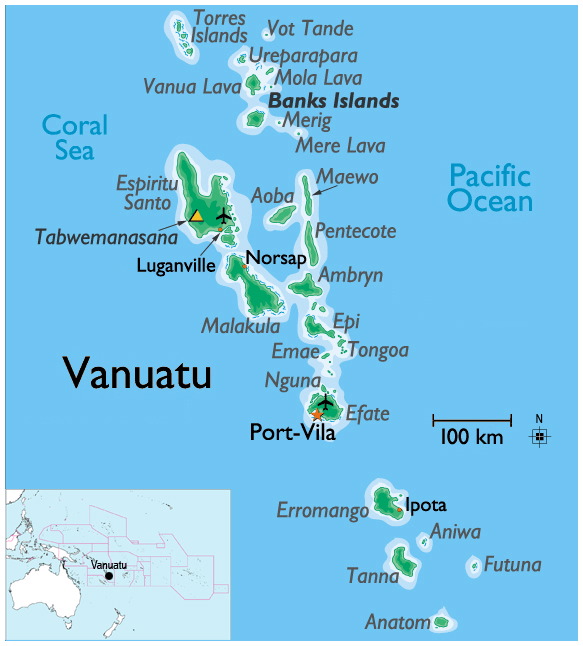

I HELD MY CARRY-ON BAG close to me apprehensively, waiting for the prearranged special security screening at O’Hare International Airport in Chicago en route to the Republic of Vanuatu, an archipelago in the South Pacific. This marked the beginning of an 11-day trip to return the remains of a man whose skull had been taken almost 100 years ago and sold for display in a museum at my university.

Many anthropologists have long framed repatriation through stories of loss to science and institutions. But I am more interested in the years between those two points—how a human was rendered into a purchasable object on the other side of the world but eventually made it back home again.

I made this trip in November 2023 on behalf of University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, as a person holding several identities and roles: I am Native American/Indigenous (a citizen of the Chickasaw Nation), an American, an anthropologist, and a poet. This is a story about human connection, acts of solidarity and care between Indigenous people and communities, and the possibility of repair within anthropology.

The field of anthropology, its practitioners, and the institutions that support it has, for centuries, taken the Ancestral remains of individuals from mostly Indigenous, Black, and/or colonial contexts without consent. Even now, the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History alone has amassed the remains of more than 33,000 individuals. Early physical anthropologists had a near-singular interest in crania over any other part of the body, with the belief the size and shape of skulls determined character and behaviors. Many researchers were specifically interested in the ways people modified crania through flattening or binding, such as through practices in some parts of Vanuatu.

Over the past two centuries, anthropologists, museum collectors, and even tourists have taken the crania of Ancestors from the islands of Vanuatu, home to numerous Melanesian groups, or ni-Vanuatu. This renders those individuals as simultaneously other and object, severing not only an individual from their burial context and community but also the wholeness of a body.

In 1924, the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, purchased the skull of a man, Atanane Elo, removed that same year from Vanuatu for US$25 to display in its Natural History Museum. The institution bought the skull, consisting of the cranium and mandible, from Ward’s Natural Science Establishment in Rochester, New York. By 2005, those remains were transferred to the anthropology department to be used in its osteology (the study of bones) teaching collection—where he remained until 2023.

IN 2023, I BEGAN the process of consultation toward repatriation on behalf of the anthropology department. We had minimal information to work with from the records of purchase. Out of the more than 900 Ancestors housed on my campus waiting to be repatriated, his is the only name we know. Working over several months with the curator of the National Museum of Vanuatu, who coordinated with a designated field guide and the individual’s family, we arranged for the return trip and reburial.

I began working in repatriation seven years ago to address lapsed compliance with the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) on my campus. This U.S. federal law was passed in 1990 to require museums and other institutions to consult with Native American Nations and lineal descendants toward the return of legal control of stolen collections.

While the U.S. does not have any repatriation or inventory processes required for individuals from non-U.S. contexts, nor those who are not Native American within the U.S., I approach all those housed in institutional collections through an ethics of care that assumes no one, living or dead, should be used for research, teaching, or exhibition without their express consent or the consent of their descendent communities: I believe everyone has the right to be returned home.

With the help of my osteologist colleagues who work in the NAGPRA office on campus, I removed the accession numbers written in ink on the cranium and mandible, and wrapped him in unbleached muslin before placing him in a padded box to protect him during travel. From there, he went into a waterproof canvas tote bag that I carried with me the entire journey. I have accompanied Ancestors within the United States, but this was my first international trip.

NADI INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT

11/26/2023

Three Fijian men

in floral shirts and sulus

played songs on stringed

instruments to welcome

arriving passengers,

creating a discordantly cheerful

soundtrack as I flagged

down a security and customs

officer to explain that

my bag would require

special screening.

There is a human skull in my carry-on.

I am transporting it for repatriation.

He nodded, eyeing me sideways,

as he read the paperwork provided,

Oh, so it’s going back to

the country of origin?

Yes, I said, he’s going home.

And just like that we were

through to the duty-free shops.

As I went to rezip the canvas bag,

I noticed how strongly

my hands were shaking.

The mode of transportation got incrementally smaller at each stage of the journey—the large planes from Chicago to Los Angeles to Fiji, to a slightly smaller one to Port Vila (the capital of Vanuatu), where the curator met me. From there we traveled together via open-air taxi in the back of a pickup truck across the width of the island before taking a final small biplane to the island of Malekula.

A small boat took us down the length of the island to a small village, where I settled into one of the two bungalows set aside for guests. Early the next morning, we took the boat around the bottom of Malekula to a much smaller island off its southeastern shore. During that last leg of the trip, pilot whales, dolphins, and flying fish provided an enthusiastic escort, leaping in front of and alongside the boat.

At the shore, a regional field guide and the community welcomed us and led us inside a building where the curator, field guide, and local leaders all made speeches, or toktok, in both their local language and Bislama, an English-based Creole that serves as the lingua franca of the country. Referred to as the “Woman who brings the skull in,” I also gave a brief speech in English that the curator translated into Bislama. While I didn’t understand everything that was said, the speakers clearly conveyed their joy at having him returned to them.

From there, we walked inland about a mile to a smaller village that included the ceremonial grounds and the prepared site for (re)burial. About 50 people attended, gathering in the shade of an enormous banyan tree.

After the ceremonies and dances for both his return and burial were performed, I was invited to place him on the intricate handwoven mat inside the hole that had been pre-dug for him. A few people made additional speeches before everyone present—children, elders, ceremonial leaders, and dancers—covered him with handfuls of sandy soil. After over 100 hours of travel, and just shy of a century of being gone, he was home.

It was striking how different his resting place—his culturally, linguistically, and ecologically diverse and rich home—was from the cold, isolated display and storage shelving where he had been for the past century, as well as the difference between how he was viewed by the community, who referred to him as “uncle” and “brother” during their speeches. One of Vanuatu’s most prominent poets and anticolonial thinkers, Grace Mera Molisa, whose poetry collection Black Stone I brought with me on the trip, wrote in her poem:

NEWSPAPER MANIA

What truth

is there

in the definitions

and descriptions

by an Outsider

who has never met

nor seen us

and is totally

ignorant

of our habitat

and environment?

This feels very true for the ways this individual and others from similar contexts have been represented within our field and in our institutions. Short catalogue entries and exhibit descriptions offer extremely limited information about these individuals and in most cases, no information at all. There is more truth to humanity—his and ours—in valuing the whole body and acknowledging enduring connections to community and place.

REWRITING THE CATALOG DESCRIPTION

Catalog description for A-1438, Museum of Natural History, University of Illinois: “Atanane Elo. Male. 25–35 years of age, of Embase tribe. Died October, 1921. Skull removed March, 1924.”

____________________

Atanane Elo of ni-Vanuatu

of fan palm, banyan, mango, nembukolit, cocoa trees

of mangroves, monsteras, bamboo, crotons

of freesia, hibiscus, mountain flowers

of clam, conch, cowrie, nautilus, tricus shells

of coconut, coconut, coconut

of swallow, pigeon, kingfisher, dove, honeyeater, white-eye, fantail, mountain starling

of blue-tailed skink, gecko, iguana, snake eels, sea snakes

of humpback, orca, blue, sperm, pilot, melon-headed whales,

of spinner, spotted, striped, Fraser’s, rough-toothed dolphins,

of barracuda, coral trout, sea bass, red snapper, grouper, parrot, flying fish

of leatherback, green, hawksbill turtles

of dugong, dugong, dugong

of yam, taro, kava

of papayas, pineapples, mangoes, plantains, bananas

of Red Emperor, parrotfish, cod, trevally, tuna, shellfish

of boar, game hen, crayfish, lobster

of mountains, volcanoes, waterfalls, rivers, black sand beaches

of azure, turquoise, denim, lapis, sapphire sea

of coral, coral, coral

During my return trip to the U.S., I was reminded about the ways in which repatriation is not just an act of losing something—we never had the right to presume to own in the first place—or missing out on some future research opportunity; this work is about reconnecting, and maybe even rebuilding—when invited—relationships severed by the behaviors of our fields, institutions, and nations.

It is not enough for anthropologists to study humans and humanity; we have to care about them too.