Co-hosts Kate Ellis and Doris Tulifau explore the perils and possibilities of the kind of fieldwork that defined Margaret Mead as an anthropologist. They provide answers to the Mead-Freeman controversy but also ask the questions that remain.

In this season finale, we circle back to the problems with coming of age … in Samoa and everywhere.

Ari Daniel

Chip Colwell

Chip Colwell

Chip Colwell

Chip Colwell

Chip Colwell

Chip Colwell

Ari Daniel

See the companion teaching units, “Intercultural Understanding,” “Using Ethnographic Methods,” and “Looking Back at Coming of Age.”

This episode is included in Season 6 of the SAPIENS podcast, which was made possible by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Can We Understand One Another?

[introductory music]

Voice 1: What makes us human?

Voice 2: Who you are.

Voice 3: History.

Voice 4: Your function in community. That’s where we find our purpose.

Voice 5: We are profoundly connected as human beings.

Voice 6: What makes us human?

Voice 7: Let’s find out.

Voice 8: SAPIENS.

Voice 9: A Podcast for Everything Human.

Kate Ellis: Throughout this season of SAPIENS, we set out to answer some pretty big questions.

Doris Tulifau: About sex and growing up.

Kate: About nature versus nurture.

Doris: About colonialism and Christianity.

Kate: But what set this season in motion—just as it set Margaret Mead’s journey to Samoa in motion almost a century ago—was the question of whether the turbulence of adolescence is something universal. Or if it varies, depending on where one comes of age.

To produce the podcast, the SAPIENS team traveled to the Samoas, where Mead went to conduct her research, and Derek Freeman went to refute it.

Doris: And we heard teens tell us about their dilemmas and challenges.

Kate: From dating and relationships to managing family expectations.

[sounds and voices in the background]

Doris: Here at American Samoa Community College, it was a ghost town. This is late May, when the students were preparing for graduation the next day. Still, we managed to find English tutor Devon Lacambra, who’s in his 20s. Growing up, he felt like his parents were pushing him to be the best he could be and with that came the pressure to be perfect. As a teenager …

Devon Lacambra: I wanted to do something other than perfect … maybe have fun with friends, have sleepovers, play video games … all those things. But that pressure of trying to retain that perfect image … I would always look over my shoulder in fear. Am I ruining my image or not? How are the other people seeing me? I was scared of losing that image.

Doris: We spoke with a variety of teenagers in American Samoa who gave us different versions of the same idea, that adolescence in American Samoa is a turbulent time despite what Margaret Mead put forward. Molesi Tafur Mora Molesi II is a 24-year-old administrative assistant at American Samoa Community College.

Molesi Tafur Mora Molesi: Growing up as a Samoan … it’s hard sometimes because you’re being protected. When you want to experience certain things or go out into the world, it’s hard. Because our brothers protect us, and then the decisions are made for us. The community plays a big role in developing and raising Samoans within the village.

Kate: These perspectives got us thinking. What light does Mead’s research from 100 years ago shed on the tumult of adolescence today? Or is it more helpful to look instead to Freeman? Does his perspective have more to tell us now?

Doris: Or is it the voices of Samoans that matter most?

[music]

Doris: This is The Problems With Coming of Age. I’m Doris Tulifau.

Kate: And I’m Kate Ellis. Today: “Can We Understand Each Other?”

In this final episode of the season, we revisit the central question of our show: Just how common is the turbulence of adolescence? We consider who got closer to the truth: Mead or Freeman.

And we go one more step. Given that both Mead and Freeman, as outsiders, struggled to see—to really see—Samoans, can we ever really understand someone from a culture that’s not our own?

Doris: Can anthropologists, whose entire discipline is based on observing and understanding communities from the outside, ever get another culture right? And what about the rest of us, especially in a polarized world where it’s often easier to focus on what separates us?

[music]

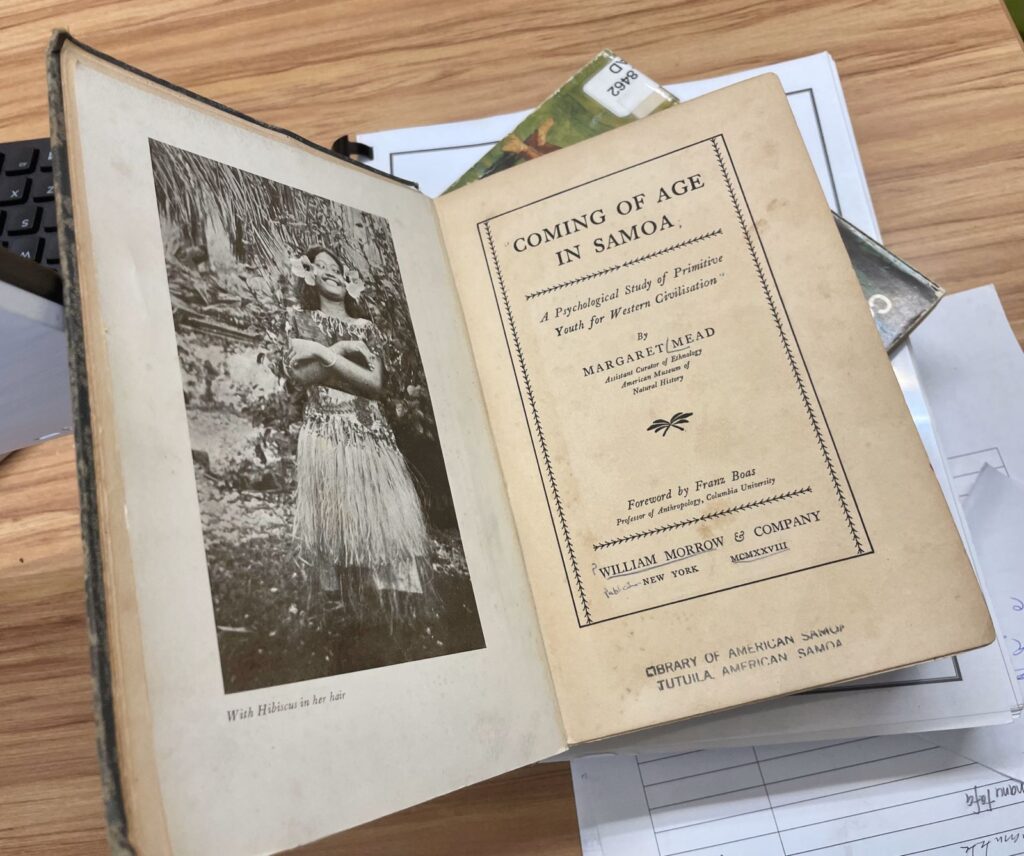

Kate: Margaret Mead spent nine months in Samoa doing ethnography to explore what she described as the easygoing and relaxed approach of Samoans to adolescence, whereas Derek Freeman spent a good portion of his career trying to dismantle her research, criticizing and undermining her thesis.

Mead emphasized culture. Freeman took the side of biology.

Bradd Shore: It did cause a stir within the field, particularly in the United States, and it tended to set biological anthropologists off against cultural anthropologists.

Kate: Remember Bradd Shore? He’s a professor of anthropology at Emory University, who faced off against Freeman on The Phil Donahue Show.

Bradd: The whole debate was like a Rorschach test. People saw in it what they needed to see for their purposes. Cultural anthropologists tended to see it as an attack on the study of culture and the importance of culture by somebody who was a biological reductionist and wanted to reduce human behavior to endocrine functions.

Margaret Mead gave a report that sex was relatively free and that young people could explore their sexuality in a relatively easy and free manner.

Derek Freeman said Samoa has this cult of virginity, and a girl will be punished or stoned if she’s found to not be a virgin. In other words, he gave exactly the opposite report.

Kate: Freeman put Mead’s contributions at risk of being discredited. And, moreover, the argument prompted further confusion and misunderstanding of Samoan culture.

People on the outside tended to see what they wanted to see, depending on which camp they were in: biology or culture. But in reality, Freeman and Mead were asking two different questions, says Shore.

Bradd: Derek Freeman is asking the question, what causes human behavior? What explains human behavior? And his answer is, it’s a bit of culture but a lot of biology. Margaret Mead probably would not have disagreed with that if she had been asking the question, what causes human behavior. In her book, Male and Female, she essentially says that. But Margaret Mead’s question was not what causes human behavior.

Kate: Rather, her question was, what explains the differences between Samoan adolescents and American adolescents? Not, how do we account for behavior? But rather, how do we account for the differences?

Bradd: And if you were to say that biology accounts for the differences between the behavior, you would have to say that Samoans were racially or biologically different, and that’s not true, and it’s not consistent with what we know.

The differences in behavior between groups are largely caused by cultural differences, and that was Margaret Mead’s only point. So Derek Freeman reframed it to make it look as if he was disproving Margaret Mead. But he did it by distorting the question.

Kate: As it turns out, both academia and the general public struggled to understand the difference between what Mead and Freeman were asking.

Bradd: Derek Freeman had the advantage in that because he was giving a flat portrait, which allowed him to make bold, simple statements about the importance of puberty and the endocrine functions and that behavior … all teenagers all over the world are influenced by this. And so the simple statements that he’s making are easily picked up by the press and are easily conveyed.

Kate: In addition, various factors contributed to making Mead’s and Freeman’s field experiences unique.

Mead began her research on adolescence in American Samoa in 1925. She ended up in Manu’a, a spot somewhat removed from the rest of Samoa, where she could observe cultural practices a bit isolated from the influence of colonization.

Bradd: She said about half the girls had had sex. That’s about what I would guess. But she failed to contextualize that and say that this sex was taking place in a society that had, in fact, a cult of virginity for high-born women, and therefore it was not something that you talked about. And Samoans would say to me, “Margaret Mead lied about our culture when she said that our girls were having sex before marriage.”

[music]

Kate: Freeman first arrived in Western Samoa in the 1940s, nearly two decades later. He began as a teacher, and he became integrated into Samoan society, to the point where he was given a chief’s title. In many ways, he had a solid understanding of Samoan culture. But he also had inherent and undeniable biases.

Bradd: Now the Samoan view of sex that Derek Freeman talks about is the official church view of sexuality in Samoa, and the Samoans defend it. The description that Freeman was giving was of the proper style of behavior for young women. And so it tended to meet with the approval of chiefs, who thought, “Yes, this is our Samoa that we like.”

Kate: Mead and Freeman both described different aspects of Samoan behavior based on each of their rather different lived experiences and contexts. That was bound to produce divergent findings.

Mead was an outsider. So she described and reported what she observed in Manu’a. Many Samoans have disputed her findings, but she claimed it was out there in plain sight for anyone to see: the cat-calling, the bawdy humor, the casual love affairs that came with what she perceived as the carefree Samoan way of life.

Freeman countered with his observations from inside the Western Samoan community. He sought out information that disproved Mead’s findings. While she said Samoans were carefree, he reported on how traditional customs were rigid and strict because of what was regarded as “chiefly,” or morally acceptable, behavior. While she claimed Samoans were consensually free-loving, he claimed rape within Samoan communities was common.

Mead described how Samoans behaved behind closed doors. Freeman laid out how they ought to behave according to cultural expectations.

Brad: How do you describe it when it alternates between incredible respect, incredible gentleness of people, and then all of a sudden, boom [claps], right? And so this is what drove me to do research there because I experienced a lot of that, and I said I wanted to make sense of this paradox of a place that has a history of being described as tranquil and as peaceful and as gentle and beautiful and then is capable of a lot of stress and violence.

And so what you’re seeing in terms of Derek Freeman and Margaret Mead is that both of them were right. And in flattening out each side of the picture and not explaining the paradox, both of them were wrong.

Kate: So here are two non-Samoans, an American and a New Zealander, who spent a lot of time—months for Mead, years for Freeman—trying to understand Samoa and Samoans.

But they still weren’t able to capture the full picture. Was it even possible?

Doris: The field of anthropology was born in the 1800s, and it’s notorious for its colonial roots, where mostly White folks went off and studied the Other.

Many notable anthropologists did what Mead did and romanticized the idea of the “professional stranger”: someone who shows up at one point in time within a community before leaving again—a person unrelated to their history. During their brief stay, this person studies a new culture, ultimately translating their observations for an at-home audience.

But this way of understanding another culture … it’s got issues.

Tapa’au Dan Aga is the executive director of the Office of Political Status and Constitutional Review in American Samoa. He says the way that American and Samoan cultural attitudes and identities were compared was problematic.

Tapa’au Dan Aga: It started off with light and dark: the West seeing themselves as being in the light and the natives as being in the dark. And Mead comes in and looks at us when we’re in the dark.

Doris: This is the issue with the professional stranger. They can’t help but bring their own biases and backgrounds to their ethnographies.

Numerous variables affected how much Mead and Freeman truly understood about Samoan culture. Yet, according to Aga, they fell victim to the same issues. He believes that Mead and Freeman, despite all of their education, or maybe because of it, still thought Samoans lived in the dark.

But Samoans—my people—weren’t living in ignorance.

Dan: Maybe we weren’t covered in the same way, but in some ways, the Samoans were more sanitary than the sailors who had been on a boat for seven months. And when the sailors first came, they didn’t find unkempt savages scrounging for food on the ground. When they came, there were actually people living here with social structures and families. And they knew love, and they knew respect. We had a spiritual consciousness, evident in our poetry and our dance and our music.

We did have a lot of problems, too. I’m not trying to make light of any of that.

Doris: The reality is that understanding a group of people takes time. And all communities have their nuances and complexities and secrets that take time to shake loose.

Dan: And we’re all guilty of it, right? I guess we take the hand down, right? And we open our eyes, and we see that there’s light and dark. The other way of looking at it and trying to understand it is sound and silence. Maybe that’s what you’re trying to do. We’ve been silent, and yet we do have voices.

Doris: Aga says the Samoan concept of va can help us connect to one another, regardless of the differences that may separate us.

Va is the notion within Oceania that refers to the context within which relationships form or exist. It makes room for them to grow and transform. Va can be between people, places, and things. Sometimes it’s a set of unspoken expectations and obligations. Va is a crucial way to nurture relationships while showing mutual respect and compassion. It’s fundamental to Samoan culture. And it’s not exclusive. Palagis, or non-Samoans, can also share va.

Dan: I have to be willing to not look at you as a Palagi for me to bridge this space between us, right? I think va can be universal. Is va only for real Samoans or can it be universally applied? [It can be] as long as we’re willing to be open to each other and share with each other and be honest with each other. And sometimes you have to struggle with each other before you really get to know a culture. It doesn’t mean you need to agree with everything about who we are. But you all seem like good people. You know, I think we can connect.

If someone tells you there’s only one way to look at this concept of va, that there’s only one way you and I can have a relationship, someone different from me and a totally different history … you know, it makes me sad.

It takes a long time to get to know another person’s culture and whether you can enter at a very personal level is not easy.

Doris: So I guess the question is, can we extend va—this centuries-old Oceanic principle—to our broader world today?

That’s after the break.

[break]

Kate: Welcome back to The Problems With Coming of Age.

Professor Alex Golub of the University of Hawaii walks through the halls of the Bishop Museum in Honolulu. He points to various artifacts.

Alex Golub: It’s now all organized by theme on the bottom floor. So you get a sense of how Pacific Islanders across the Pacific did things like honor their ancestors, get their food, trade, rule, and organize themselves.

Kate: He says the Bishop Museum has tried to reverse an outdated mindset around the cultures of the Pacific, or what it is being called today the vast Blue Pacific.

Alex: They’re trying to move out of that “islands” focus, where each island is a separate laboratory, the way that Mead imagined it was, and try to understand the islands as interconnected, which they really are.

It’s not a bunch of different, bounded islands separated by the ocean. People now think about the Pacific as being an oceanic space that connects people. People talk about themselves being from the Blue Pacific or Oceania and being part of a broader cultural realm.

[music]

Kate: As anthropology evolves and updates, it has prioritized raising up marginalized voices. Golub says that perhaps the key to deeper mutual understanding is choosing to learn from people within a community rather than from an outside observer.

That’s why, when he teaches about Samoa, he doesn’t even consider assigning Margaret Mead’s Coming of Age in Samoa to his anthropology students. He thinks she’s yesterday’s news.

Alex: She’s been dead for half a decade, and it’s from the last century, and we have better work since then. The only people who want to read Margaret Mead are my Samoan students. And they want to read it to trash it.

But critically engaging with it and learning how to critically engage with it is important, but young people who are fired up don’t really always have the patience to learn that lesson when it’s a topic that’s so close to home. So it’s just like, “God, can we move on? I’d rather teach Lisa Uperesa’s new book.”

Kate: Golub’s got a point. But in my view, it’s not the full story.

Mead and her work in Samoa contributed to anthropology’s evolution: It’s becoming more nuanced and reflexive over time. Mead’s career shaped the movements that helped empower advocacy for less visible and marginalized groups: women, children, Indigenous peoples.

Because of Mead—and even the controversy with Freeman that her work fostered—anthropology has developed new methods. Anthropology now views culture not as fixed, rigid, or permanent but rather as flexible and fluid. Ethnographers today do not see communities as static cultural laboratories as Mead did but as interconnected nodes in a globalized world.

Alex: One of the things that we need to get past is the idea that there is a culture, which is like a giant circle with a bright, clear line around it, and some people are inside the circle, and some people are outside of it. We’re much more interested in having people from all kinds of subject positions, all kinds of walks of life, doing studies of all kinds of other different people. And that line between their culture and our culture was never theoretically sufficient. It was never empirically adequate, and we have to move past that.

Culture is not externally bounded and internally homogenous. That was the fundamental Boasian insight. Cultures change. They move. Culture traits cross borders.

Kate: And this means including more “insider” anthropologists.

Doris: Like me!

Kate: Yes, exactly. We need to look to Samoan academics, writers, researchers, and, yes, Samoan anthropologists for their perspectives and stories to better understand their culture, their authentic portraits, each one telling a different part of the broader Samoan story—giving those of us on the outside a better sense of what Samoa is all about.

[music]

Doris: That’s why I wanted to be on this podcast, to make sure that if we talk about Margaret Mead and what she did, and Derek Freeman, I’m going to make sure that I’m a part of a team that allows our voices to be heard this time around. This is the chance for me to make other young Samoan anthropologists come out. I’m not saying that we need to write a book against it, but our voices need to be heard.

Kate: It was interesting to learn more about Margaret Mead and to dive into the controversy between her and Derek Freeman and to think about some of those larger issues around nature versus nurture and the nature of sexuality and also to dive into some of those questions of how do we ever know another person or another community.

Where do you come down on that?

Doris: I think that we always have to make sure that if we’re talking about another culture we have the right people in the room; that if we have a platform that’s going to speak on a community, there’s a seat available for that community, to make sure they’re telling their story, and that we figure out a way to amplify that—not someone else that’s not part of that culture to tell their story.

And I’m seeing that more as I’m doing a lot of work now, in 2023. We get it. I think the world gets it. I see that everyone’s making seats available. I see White people taking the back seat way more … not trying to be written by them but making sure that you see the names of all these Indigenous people first and people taking a step back.

You know, one day there’ll be movies about my Pacific community in Polynesia, and I have to make sure that they can reference books that are not Margaret Mead or Derek Freeman that actually talk about our history and positivity and all the great things—and the bad things—but not in a way where it’s this huge debate on who knew Samoans more.

Kate: To the extent that this podcast centered voices of Samoans and your voice and others around you, to me that was my favorite part of this series.

Yeah, I think that this kind of work takes a ton of humility. I don’t want to say we can’t ever know another. I don’t think that to me personally makes complete sense, but I do think it takes humility. I can’t totally know what your experience was like. I didn’t walk in your shoes. But I can have empathy. I can have imagination. I can be curious. I can listen.

I was in anthropology. I’m now in journalism. My whole profession is about talking and going into other communities that we’re not a part of and writing about, and asking people about, what’s happening to them right now. I think we can do that in thoughtful, credible ways because part of the larger project for me is actually to advance understanding and to, through writing and interviewing and talking, actually try to help people understand one another.

That’s actually what my mission is about, in a sense. I think there will always be people who will say, “Kate, you don’t have a place here. Step back.” And other peoples who say, “Pull up a chair. I am so glad you asked.”

Doris: I think that’s the same thing for me. And I think that’s why I say, “I’m learning as I go,” and I keep taking people with me that are part of my community and that should be the experts. And I think that’s what we learn as we go. Culture evolves, and things change. There isn’t any books. There’s just a gap, and how do we fill that gap?

[theme music]

Kate: The Problems With Coming of Age is a co-production of SAPIENS and PRX Productions.

Be sure to check out the season’s college curriculum, historic photographs, and so much more on our website: SAPIENS.org/podcast.

Doris: This episode was written and produced by Rithu Jagannath, Ashraya Gupta, and Ari Daniel. This season was hosted by Kate Ellis and me, Doris Tulifau.

Kate: From SAPIENS, we were supported by Chip Colwell, Tanya Volentras, Esteban Gomez, Sia Figiel, Salamasina Figiel, Sophie Muro, and Christine Weeber. The season’s humanities advisers were Danilyn Rutherford, Lisa Uperesa, Nancy Kates, David M. Lipset, Nancy Lutkehaus, Agustín Fuentes, Don Kulick, and Paul Shankman.

Doris: And fa’afetai to the more than three dozen people we interviewed in American Samoa and Samoa for helping to shape our understanding of this story.

Kate: The executive producer of PRX Productions is Jocelyn Gonzales. The project manager of PRX Productions is Edwin Ochoa. The business manager is Morgan Church.

Doris: Dan Taulapapa McMullin created the season’s cover art. Celina T. Zhao was the fact checker.

Kate: Audio mastering by Terence Bernardo.

Doris: Music by APM with additional tracks by Malō Fa’amausili recorded at Apaula Studio as well as songs kindly provided by Bobby Alu.

Kate: SAPIENS is part of the American Anthropological Association Podcast Library.

Doris: And SAPIENS is an editorially independent podcast funded by the Wenner-Gren Foundation, which has provided vital support. Our thanks to the foundation’s entire staff, board, and advisory council. Season 6 of the SAPIENS podcast was made possible by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

I’m Doris Tulifau.

Kate: And I’m Kate Ellis.