Are Insomniacs Overthinking Sleep?

You will likely spend about 26 years of your life sleeping. You’ll use up another seven years just falling asleep, and for many insomniacs, that doesn’t include all the doomscrolling, clock-watching, and listening to purposely boring podcasts in the small hours of the night. Insomnia rates vary widely by culture and demographics, but the consensus is that about 30 percent of adults worldwide have difficulty sleeping.

Bad sleep is bad in many respects. Those of us struggling to slumber are more likely to have worse physical and mental health. Sleep problems disproportionately affect people living in inadequate housing in low-income neighborhoods, due in part to environmental stressors like poor air quality, noise, and extremes in temperature. And sleeplessness is likely to increase with more and more anomalously warm nights on the horizon.

So, it’s little wonder that so many people toss and turn over how to improve their sleep, relying ever more on technological aids.

The sleep tech industry is worth billions of dollars (but not quite as many billions as lost sleep costs the U.S. economy). You can buy a smorgasbord of gadgets. Weighted blankets. Heated mattresses. White noise machines. Fake-sunlight lamps. Special pillows. Earplugs. Nose plugs. Smart watches and rings. And a range of masks that could belong in an ethnographic museum. And that’s before we get onto antidepressants, benzodiazepines, and other drugs.

But evidence for the effectiveness of many forms of sleep tech seems to be low or lacking.

Some techniques work, though. Treatments from the world of mental health—particularly cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)—do have scientific backing. You can now access CBT on your smartphone through apps like Sleepio (which the U.K.’s medical advisory agency recently recommended as a treatment for insomnia).

Worrying about sleep occupies a lot of our waking hours and is translating more and more into strains upon our wallets. But this might not help as much as following some very old approaches to sleep designed by the greatest engineer in the world: evolution.

Compared with other primates, humans are odd sleepers. We have the shortest sleep duration among our evolutionary kin. Some, like the wonderfully named three-striped night monkey (which conjures delightful images of a simian gallivanting in silk pajamas) spend a whopping 16-plus hours asleep each day. A variety of monkeys just nod off clinging to a tree.

In fact, sleep tech is fairly minimal across the animal kingdom. My cats actively shun all the plush sleep aids I’ve bought them. They favor splaying across my keyboard while I try to write about anthropology for you fine folk.

Among humans, in many places around the world sleep tech is simply a mat woven from leaves spread out on the floor. And how people sleep upon them varies a great deal. Anthropologist Carol Worthman gives examples of how fluid, communal, and seemingly chaotic sleep can be in forager societies such as Aché in Paraguay, Efe in Zaire, and Ju/’hoansi in Botswana. For these communities, she says, the night is full of “ritual, sociality, and information exchange.”

On the other hand, a quantitative study of sleep patterns among Ju/’hoansi people, Hadza foragers in Tanzania, and Tsimane hunter-horticulturalists in Bolivia found that sleep duration wasn’t markedly different from that in industrialized and post-industrial societies. People tended to sleep right through the night, while length of sleep varied depending on the season, with nearly an hour’s extra slumber during winter. Notably, participants experienced virtually no insomnia.

In a seminal anthropological study, Polly Wiessner found that firelight extended the days for Ju/’hoansi people, who would spend the extra hours singing, dancing, telling stories, and engaging in intimate conversations flecked with flames until the fire faded. Some would awaken for a “little day” around 2 a.m. to smoke, chat, and stoke the fire to ward off predators.

Gorgeous, flickering amber light might be just what many people need. While writing Chasing the Sun, journalist Linda Geddes spent several “dark weeks” without artificial nighttime light. She found the candlelight improved her energy levels and mood. And studies have shown that soaking up more daylight helps regulate circadian rhythms and might lead to better sleep.

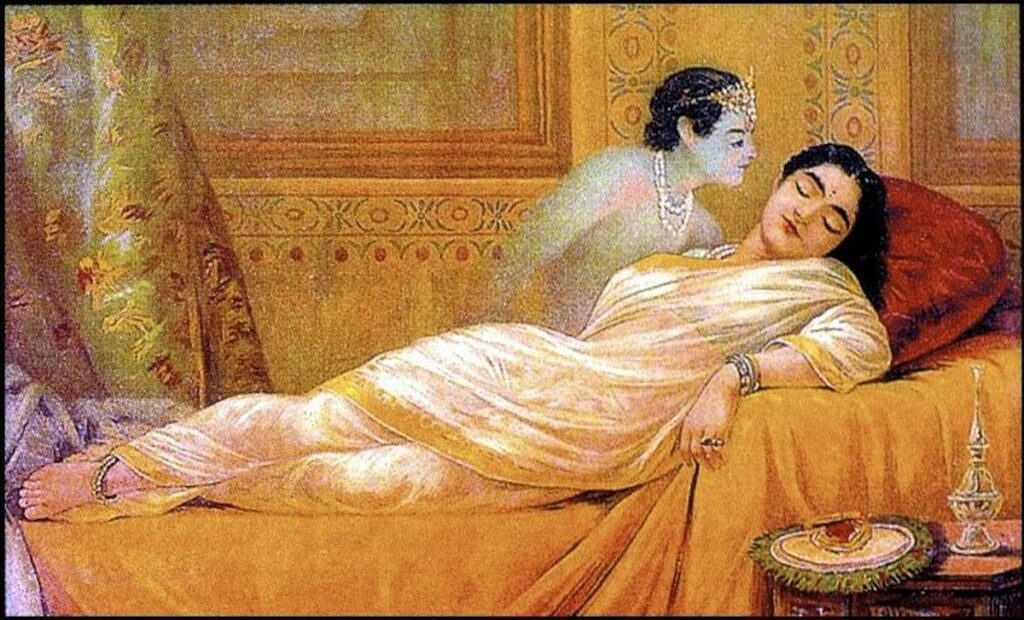

Yet anxieties around sleep are not solely a phenomenon of Western, industrialized cultures. In some places, sleeping is never something you should do alone. People living in Manggarai, on the Indonesian island of Flores, believe you’re vulnerable to being visited by spirits while asleep. Friends and relatives will turn up to sleep alongside you if you live alone.

In addition, anyone can suffer from insomnia when experiencing major life transitions or being thrust into unfamiliarity. A recent ethnographic study shared how a young Gaddi woman in Himalayan India, for example, was unable to sleep in a bed after getting married. Instead, she preferred to curl up by the hearth.

Perhaps many people would value sleep differently if we put greater stock in our dreams.

Our dreams may serve many purposes. Some of the more mechanistic explanations explored through scientific methods suggest dreams help our brains to fine-tune their function as squidgy prediction engines. Dreams could do this—and so much more.

As anyone who remembers a nightmare will tell you, people perceive the beings and temptations and dangers in dreams as real, no matter how nebulous and shifting. And in the dream, you interact with them as if they are real.

What if dreamworlds and dreamscapes were seen as a different kind of reality, not something altogether unreal? These are places where dead ancestors return to advise you, where gods offer divination from divine places, where ghosts become visible, where solutions to today’s problems arise, or the location of tomorrow’s prey is revealed. For Asabano people in Papua New Guinea, dreams offer evidence for supernatural beings and help dreamers contend with religious ideas; they are considered the “real experiences of the soul.”

Mehinaku people in Brazil share and interpret dreams as a means of understanding themselves and their world. Perhaps people in many industrialized Western cultures should learn from this and spend more time together collaboratively exploring the experiences attained in our dreamworlds, much as more and more people in post-Enlightenment nations are beginning to value other states of consciousness, such as visions, trances, meditations, and psychedelic journeys.

Those of us living in supposedly “modern” yet highly unequal societies spend a lot of time and money over-medicalizing and over-engineering sleep. Until nations get serious about tackling inequalities—along with other issues such as light pollution and increasingly warm nights—too many people will be trapped in environments not conducive to slumber.

But examples from anthropology suggest that the solution to sleepless woes might be social and societal, not technological. Even the most effective sleep tech, like Sleepio, is fundamentally social. Cognitive behavioral therapy is a talking therapy, after all.

So maybe the key to restful nights lies less in gadgets than in communal activities like sharing dreams and seeing out the dying embers of the day together with stories and song.