Peeling Back the Myth of a “White” Midwest

A desolate windswept field, bisected by a two-lane road, fills the television screen. The camera pans over a man’s dusty hat on the seat of a truck, the tip of his cowboy boot, then up to a pair of grain silos, and finally to a tiny clapboard Christian church. A gravelly masculine voice intones, “There’s a chapel in Kansas, standing on the exact center of the lower 48.” Swaying wheat stalks move through the frame, light filtering through their silhouetted branches.

The narrator of this two-minute Jeep ad, which aired to around 96 million viewers during the Super Bowl in February 2021, is none other than singer Bruce Springsteen. With few visual references to Jeep products, the ad is focused instead on reaching across political divides by identifying commonly shared U.S. values. “All are more than welcome to come meet here,” Springsteen says, pausing before adding, “in the middle.”

He continues: “It’s no secret the middle has been a hard place to get to lately, between red and blue, … between our freedom and our fear. Now, fear has never been the best of who we are.”

While Springsteen talks in a solemn, almost reverent tone, more images follow in quick succession: a shiny-coated horse, a waving American flag, a diner. Springsteen himself kneels and lets a handful of soil fall through his fingers as he reminds viewers to remember their “common ground.” A crescendo of fiddle strings sonically closes out the ad, the setting sun again visible across the rural landscape.

There is a lot going on in this ad, pointedly titled “The Middle.” Perhaps most obviously, it communicates an overriding sense of mourning or nostalgia for a certain version of the United States—a tacit understanding of the way things once were and perhaps should be. In some ways, this longing is connected to the real hardships of deindustrialization in the Midwest and beyond. What the commercial does not do, at least not in a direct way, is talk about race. And yet, it is implicitly about white folks—or, better said, about white suffering and white loss.

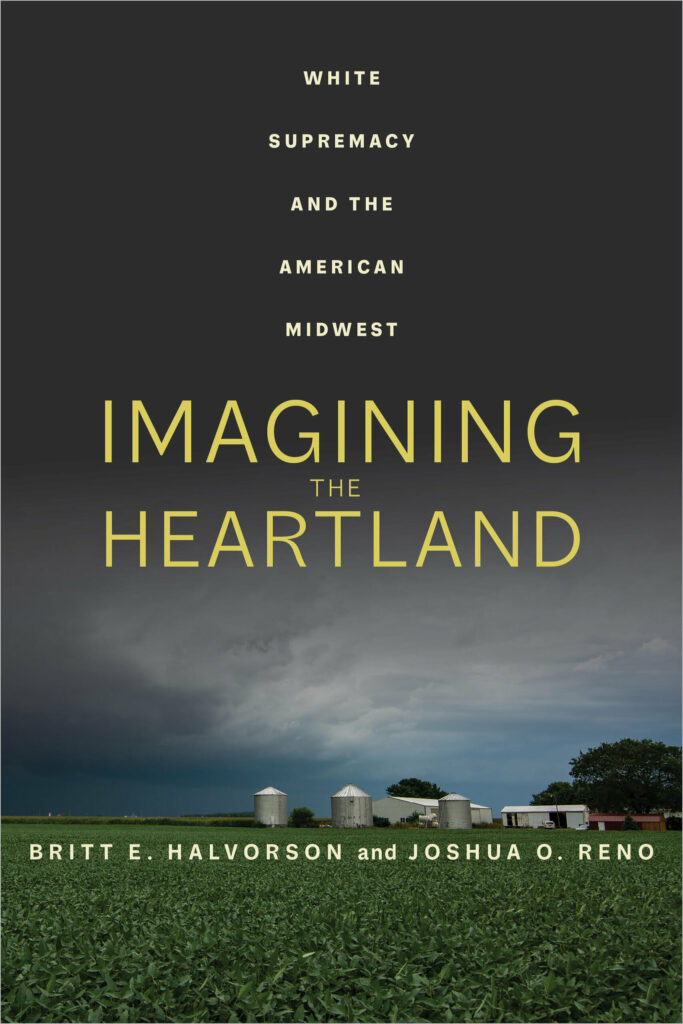

Our new book, Imagining the Heartland, is about the Midwest and its role in shaping white supremacy in U.S. culture. Whiteness, we argue, is often inchoate and hard to recognize—and that’s key to its enduring power. Not only is it a form of identity or a reference to a person’s skin color but also a cultural system of power and resources that many individuals participate in without being fully aware of it. Narratives and practices centering white individuals and families remain dominant precisely because they are so ubiquitous and seem neutral.

Read on, from the archives: “Why We Need a Truth Commission on White Supremacy”

Public discussions about Black experiences in the U.S., by contrast, are often framed as inherently political. School book bans have recently surged nationwide, with many targeting titles about Black experiences—from Angie Thomas’ The Hate U Give to George M. Johnson’s All Boys Aren’t Blue, among others. As part of a broader wave of book bans and removals motivated by issues of race, gender, and sexuality, proponents of banning often use coded claims that censored titles contain “divisive” or “controversial” material, particularly if they deal with race and racism.

Meanwhile, the implications of banal cultural messaging like the Jeep ad often go unnoticed. While the ad did draw some criticism, it failed to spark widespread public conversation about race and white supremacy back in 2021, even though it was shot and aired just weeks after the January 6 insurrection. That’s because U.S. Midwestern tropes—verdant fields, small towns, flat terrain—have long been associated with whiteness and the traits that supposedly represent the best of America: white virtue and hard work, as well as white self-governance and practical reason.

Whether we realize it or not, heartland imagery is never as banal as it seems.

Among other things, white loss and white nostalgia are central but less publicly discussed dimensions of so-called replacement theory. This racist fantasy foretells of a future U.S., supposedly deliberately engineered by (usually Jewish) elites, when white people will no longer be a numerical majority. Replacement theory relies not just on fear of “others” but on imagining an ideal community, self, and world in peril.

Replacement theory moves people, at least in part, by producing an emotional state of longing: a desire for a particular way of life, one that seems worthy of protecting and fighting for. This longing incites a select few—such as the recent mass shooter who targeted Black shoppers at a supermarket in Buffalo, New York—to extreme violence.

As we see in the Jeep ad, the desire for such a mythical past is tied not only to whiteness but also, even more explicitly, to heterosexual masculinity and Christianity. That way of life might never have existed in the lives of Jeep ad viewers, but some are nevertheless sure it existed somewhere, somewhere in “the Middle” they’ve never been to but have seen depicted, painted, and conjured over and over again.

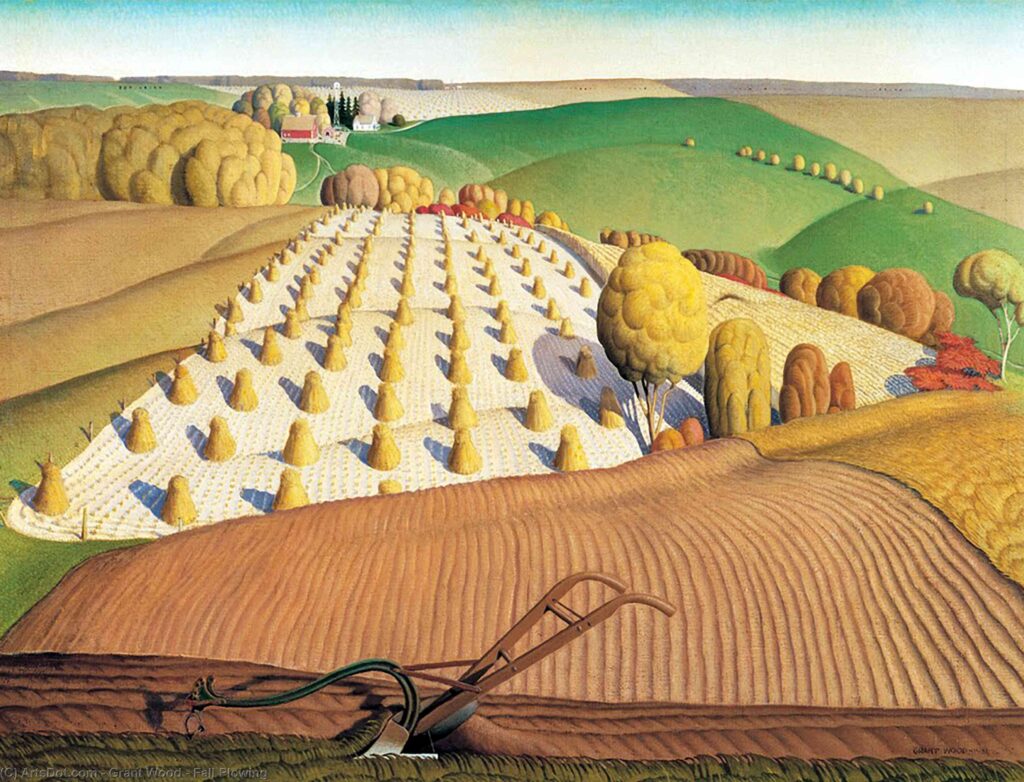

In our book, we show how widespread imagery of the Midwest, from the 2021 Super Bowl’s “The Middle” ad to Grant Wood’s mid-century paintings of farm fields, shares an often-unexamined relationship with shifting forms of white supremacy in U.S. history. National narratives about white settler economic and political interests have long deployed images of boring, plain, and ordinary white folks and rural landscapes of the Midwest—regardless of how accurately those images represented or spoke to those who chose to self-identify as “Midwesterners.”

So, where did this idea of “the Middle” come from? As early as the late 18th century, Thomas Jefferson saw the small-scale farmer as the heart of democracy. But the broader cultural investment in the idea of the rural heartland started taking shape about a century later. The “Middle West” came to be nationally and globally recognized as a distinct region in the post–Civil War era—a time when industrialization was creating new forms of economic and political authority, labor, and social inequality.

This impulse to associate ordinary geographic centers with a kind of golden age of rural life was not limited to the U.S. in the early 20th century. Other industrializing nations, including Japan and Germany, began promoting rural heartlands as a nationalist ideal around this time, in contrast to the allegedly cosmopolitan and corrupt values and populations of the growing cities. The regional identities of “rural” and “urban” began to stand in as phantom cultural figures expressing opposed political sentiments and sensibilities in all three countries—a division that has come to be taken for granted today.

However, this romanticized view of the rural heartland in the U.S. was never accurate. In reality, much of the Midwest has long been industrialized and tied into global markets. Today when paintings, films, commercials, news reporting, and television shows repeatedly depict the Midwest as filled with rural landscapes of wheat and corn, they help conceal the actual economic history of the region—both the industrialization of agriculture and the presence of many other kinds of industry.

As historian James Belich describes in his book Replenishing the Earth, mercantile trade, finance, grain milling, and skilled trades like blacksmithing were a central part of the division of labor in the Midwest from the early 1800s on. In a survey conducted in 1850, only 53 percent of the workforce in settlement boom-time Wisconsin described themselves as farmers. And even those who answered the survey in this way were not merely describing what they did for a living when asked, “Are you a farmer?” This job description was also an aspirational category tied to landholding, not always an economically viable full-time livelihood.

The Midwest’s long-ignored industrial past—including mining, forestry, and the work of constructing new farms, railways, and roads—has elicited ire from scholars keen to set the record straight. As geographers Brian Page and Richard Walker write, with a hint of frustration, “No historian of the Industrial Revolution in Britain imagines that it involved trade, information, or division of labor alone; every account of British industrialization (or that of New England) emphasizes the development of machinery, the factory, new metallurgy, the steam engine, labor skills, and management. Why is it that in discussions of the Midwest all this appears to be forgotten?”

Page and Walker point out that this association with industrial manufacturing can be completely left out of the picture of the Midwest whenever one chooses. By performing a sleight of hand, the region is represented as traditional, agricultural, bucolic, and old-fashioned. As just one example among many, they go on to argue that, contrary to this pastoral image, the steel industry came to deeply shape the economies of northeast Ohio, northern Indiana, and Illinois.

All of this points to an important insight: By the early 20th century, small-scale rural farming was an ideological construct with national and global significance, rather than an image that accurately reflected the economic diversity of the Midwest region.

To be clear, the Midwest region does, of course, include bucolic landscapes of corn and wheat fields in some places, and more than a small number of Midwestern rural areas have relied on farming as their main livelihood. But that alone does not account for the longevity and homogeneity, one might even term it the cultural monocropping, of rural heartland tropes.

So, why has the homogenous image of the rural, farming Midwest, so persuasively mobilized in “The Middle” commercial, persisted for so long? And why has it gained heightened significance at certain times, even in the face of substantial, widely available evidence that challenges or complicates it?

Answering this question requires understanding how these heartland narratives support ingrained systems and ideas of white supremacy. The iconic white Midwestern farmer, like the idea of “The Middle,” was invented.

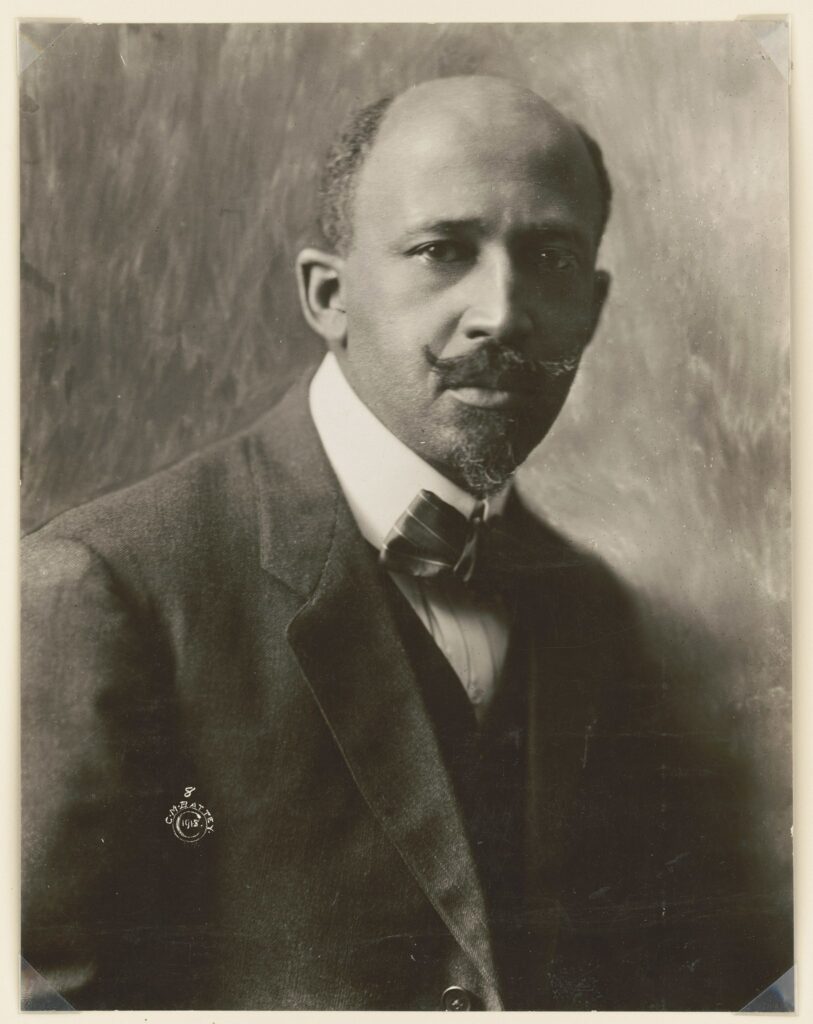

The white rural citizen was imagined to be humble, hardworking, and productive in cultivating the land. This contrasted sharply to Indigenous communities who were stripped of property rights to ancestral land in order to pave the way for white settlement—all on the incorrect basis that they did not farm or “improve” the land. As sociologist W.E.B. Du Bois noted in 1920, this virtuous, usually male laborer, literally making things from the ground up, was the white moral center of an increasingly divisive set of arguments about race, belonging, and nativism in the U.S. beginning in the Reconstruction period.

Historians Marilyn Lake and Henry Reynolds build on Du Bois’ work to demonstrate the global reach of these racialized identities. They show how the racial binary of white/color was formed in ongoing dialogue not only with the aftermath of the U.S. Civil War but also with global projects of empire and colonization. European and American policies justifying colonialism depended on this heroic version of the white rural farmer. The idea of the “white man’s burden” presented imperialism as a duty—claiming that only white men could be trusted to properly steward the land and people in places like the Philippines, Australia, and South Africa.

Public images of white progress and power were part of claims to retain land and political authority, sometimes in direct response to anti-colonial uprisings around the world. Writing in 1910, Du Bois strikingly observed, “Wave on wave, each with increasing virulence, is dashing this new religion of whiteness on the shores of our time.”

So, today whenever a Super Bowl commercial or commentary by an election pollster represents the Midwest and its people as more or less uniformly white, rural, and salt-of-the-earth, they are partaking in an old and established tradition. Whether we realize it or not, heartland imagery is never as banal as it seems.

White supremacy’s violence is not maintained solely through physical attacks. Much of the work that white supremacist discourse performs, culturally, happens beneath our notice, during commercial breaks, and in between plays on the field. Romanticized images of the heartland quietly seed the field of white nostalgia and white resentment that racial violence mobilizes, row by row, planting an imagined way of life that never was.

Editors’ note: Portions of this essay have been drawn from the authors’ book Imagining the Heartland.