A Poetics of Liberation: An Imagined Archive

As a historian, poet, writer, and experimental sound practitioner based in Tanzania, I meddle in different tongues—testing which one has the least bitter aftertaste. For, I work extensively on Tanzanian heritage and human remains entrapped in Germany.

In my work, I do not try to balance the blood-tinged scales of history, nor do I write toward retribution. The time for that has passed. What has been taken can never be recovered, at least not fully.

I do not offer any answers, solutions, or words of consolation. Rather, I offer a gathering of poems, a voice reading them, and the commitment to be in communion with this troubled history. Alongside other scholars and poets, I conjure alternative realities of the violence of historical atrocities, trafficking, brutality, and defilement that do not rely on the notes of the murderer to provide an account of the murdered.

These notes are said to have begun in the late 1880s to 1919 when Germany colonized what was then Tanganyika as part of “German East Africa,” which also included present-day Burundi and Rwanda. However, the reality is that the process had started as early as the 1860s with proto-colonialists, missionary men and adventurers, geographers, and botanists.

I engaged with this history in my poetry project for SAPIENS as the 2024 digital poet-in-residence. My Imagined Archive was where I could envision what conversations with those who do not appear in official records could sound like. Here, I could take the handful of facts I had on Black African women—their lives in a footnote—and expand them to be something more. Here, I could construct something else, even if the first stone was from rubble. Here, I found poetry to be a language of liberation.

FORGING A PATH OF LIBERATION THROUGH POETRY

How can we, as artists and creative practitioners, access the past when a linguistic border separates us from human stories and speaks only of statistics and numbers? How can historians speak of people’s agency when colonial archives blur nuance into a gaping abyss? How can we, as social scientists, claim to denounce the violence of history when we use the same methodological tools that birthed it? These questions, among others, propelled me during my residency.

As a historian, my practice is defined by facts, sources, and evidence. The work centers on a persistent demand—or at the very least, consideration—for proof and “objectivity,” an end goal that is not always achieved. Despite my training and my experience with adjacent fields, such as anthropology and philosophy, I became increasingly disdainful of the sprint toward objectivity—an oasis mirage, especially as a historian of Africa.

The seeds for my 2024 project at SAPIENS were initially planted when in 2022, I was selected as one of the fellows for the Sensitive Provenances Research Project hosted at the University of Göttingen in Germany. The project saw researchers, practitioners, and museum experts unpacking the legacy of the morbid practice of collecting ancestral human remains that was popular in Euro-American circles in the 19th and 20th centuries. This pseudoscientific “research practice” resulted in the creation of a distinct field of racial science, a hierarchy of skin and bodies, a taxonomy of life.

In encountering this history so viscerally, I was repelled by the language of objectivity and the callousness of facts.

What would the past look like without “fact,” I thought, without “objectivity”?

Alternatively, poetry became a language of possibility, of recovery, of an attempt to hold what should not be held.

As I continued to encounter ethnographic collections with heritage and ancestral human remains from my home country, I became convinced that to engage this history, I could not use the language of dimensions, inventory, specifications, and fact. I turned to poet Audre Lorde’s timeless epitaph: “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.”

I also turned to other Black feminist theorists who dared dream beyond a world of “reason” and “rationality,” such as Saidiya Hartman, Dionne Brand, Katherine McKittrick, Octavia Butler, Grace Nichols, Una Marson, and Toni Cade Bambara. I wrote accompanied by these Black women who refused to be resigned to the margins, who refused the imprisonment of defeatist narratives.

I set out to merge the findings of my historical practice with the elusive language of poetry. The archive became the construction site, the playing field where I would attempt to tune into the frequency of marginalized voices—not to give them a voice but to find a way to hear them better.

CONSTRUCTING AN ALTERNATIVE ARCHIVE

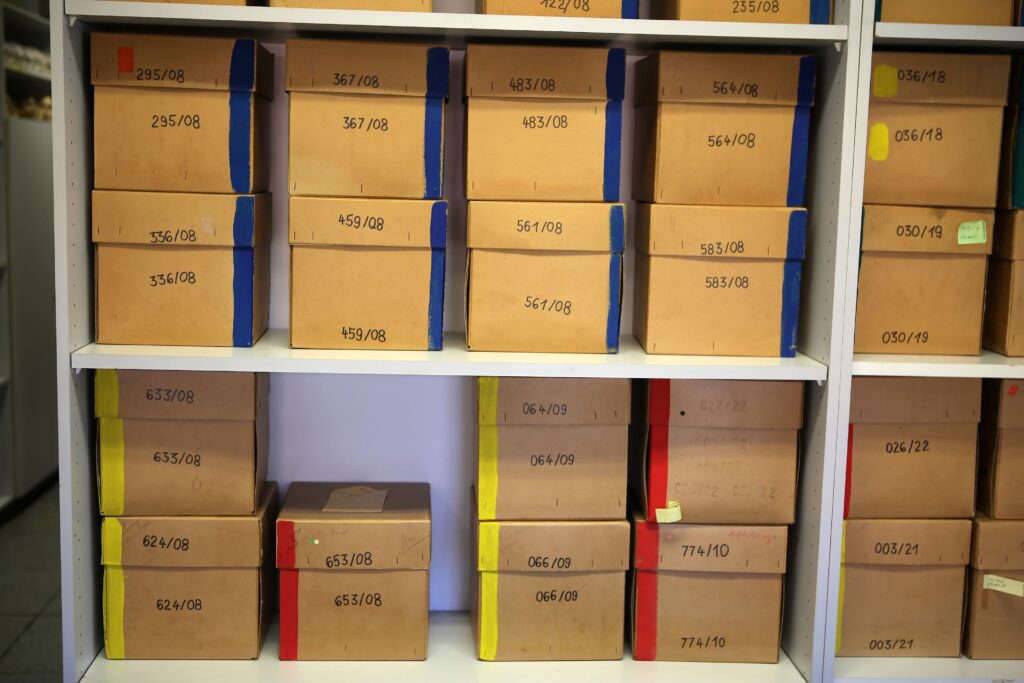

In my experiences in museum storage rooms, laboratories, and university collections, I could never find stories of people who looked like me. The archive was a burial site. I mourned the death of stories, lamented over the empty page, and plotted how to go against my historical training.

In trying my own hand at an archive, I use imagination to make up the walls, speculation to put in the flooring, and poetry to fill in the bare shelves.

Take, for example, the poem “An Imagined Monograph for Nongqawuse.” I first learned of Nongqawuse’s account in a history course on South Africa. The story of a 19th-century Xhosa prophetess who led a pivotal cattle-killing campaign amid British colonial resistance campaigns struck me. Her story is well known but shrouded in mystery, judgment, and shame. Poetry allowed me to imagine her passing through the “hall of history,” the way she “enters the archive / under the weight of shame, / soaked, she shuffles in with / endless rivulets of blood / embedded in her small palms.” Through poetry, I could imagine her human condition along with her categorization in history. In this iteration, she became more than a disgraced historical figure.

In “Coastal Eden,” I interrogate Creationist narratives and the blame often assigned to “First Women.” I imagined Eve’s internal thoughts amid this blame, how she may have resided in the garden, “in tears, / wanting to know why her / and not the tree.” Poetry gives these historical women voices, as well as counterarguments to the accusations hurled against them.

Not all my experiments have distinct historical figures. In some, I listen for and try to sense unknown women. “The Visit” and “Nameless Woman” both use the conceit of a blurred, shapeless figure to try to capture the experience of working in archives and museums. In “The Visit,” I imagine how this figure “sits in the corner, / outlined faintly by the soft glare of the moon. / she does not wear clothes, no nightrobe, no plush slippers. / there is no spine to turn, no torso to twist, only the / sobbing.” Similarly, in “Nameless Woman,” the unknown speaker uses direct address to describe how her “body has folded into itself / sprouted brown mold, like rotting fruit / dropped almond, fermented sugarcane.” The poetic voices of uncertainty show what researchers, descendants, activists, practitioners, and mourners face when looking for African women in historical records.

I have found a poetics of liberation, a language that does not conform but dreams of new possibilities.

This methodological reality can also be seen in “Archived Haints” with spirits “whose skin / has turned to thin yellowed paper. / their hollowed faces discernible / only by the ruthless curves and / lines of numbers and catalogues.” “Her Dirge” personifies this act of historical research by characterization. The opening line, “memory is a washerwoman,” shows the emotional cost of doing historical research, especially when histories of women are frequently sidelined.

My poems are a call to action. In “Survival Notes,” I recognize the tradition that so many women before me started. My poem offers a rallying cry to survive despite the calculated assault, “the Maangamizi.” I urge others to make something out of the debris, to “find a surface to etch your name / onto, into, even when paper / becomes flesh. [to] trust that despite / the deluge, they will find you.” I acknowledge Black women who are trying to access their heritage. That they may have to hold onto the jagged knife of history but can find something else to write of it beyond the broken body.

This Imagined Archive has become a project that perhaps can never be finished.

I write into the abyss, into the cracks where many have fallen. Poet Dionne Brand’s pledge to write “towards liberation” guides my work. She speaks of the impossibility of justice, an impossibility I agree can never be attained. Her poetic philosophy is to move beyond the “state of tyranny” where those who have faced historic violence may be tempted to reverse the timeline of history but in the process, they may legitimize the violence of tyranny itself. As such, she rejects the idea of “justice” and moves toward liberation instead, beyond the constraining parameters of structures and the past.

I resonate with this idea, as my historical practice is defined by borders, resources, and labor of nation-states and their creation. My poetry allows me to throw these notions into the air—to question the infallibility of cartography, the dominance of the colonial project. Poetic language allows for meandering, for opacity, for freedom from categorization and classification. It allows because it cannot be pinned down. I have found a poetics of liberation, a language that does not conform but dreams of new possibilities.

I return where I began, asking questions, mourning people robbed of an afterlife, calling out names where there are none listed on paper. I do not demand the burning of the archive, that would mean destroying the few scraps where these individuals do appear. I continue to offer this language and hope that is something to hold onto. I construct in territory that has long been marked conquered by others. I continue meddling in different tongues—with poetry a space to speculate, to fill. A language whose aftertaste I can withstand and not spit out.