Natural Disasters Are Social Disasters

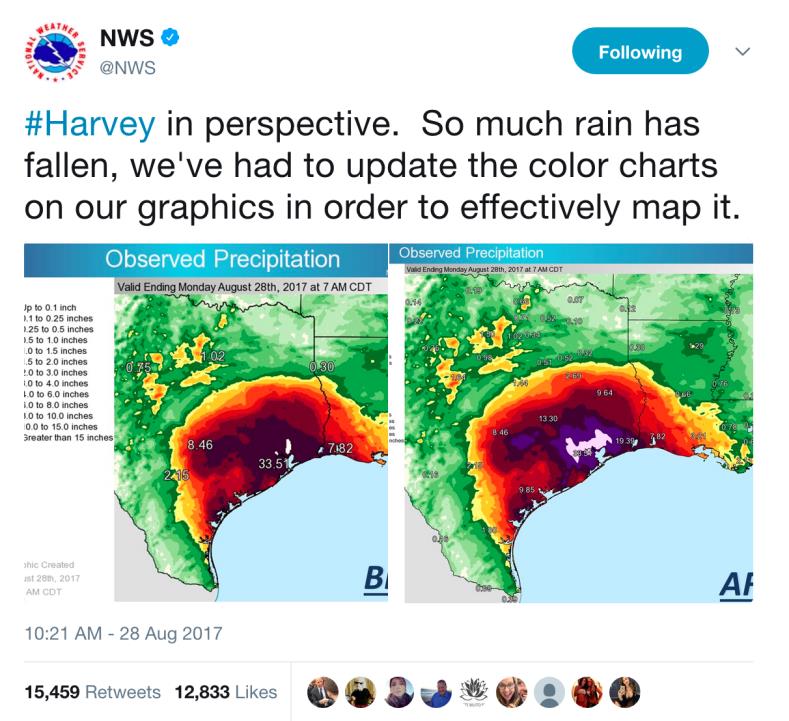

When Hurricane Harvey dumped more than 4 feet of rain over parts of Houston in August, the National Weather Service needed two new colors for their rainfall maps: Areas of dark purple and lavender now show amounts of rain from 20 to 30 inches, and above. The weather service called the storm “historic and unusual.” More than 80 people died as streets and homes were submerged in muddy, toxic water. According to the Federal Emergency Management Agency, 122,331 people and more than 5,000 pets were rescued during the storm.

In the weeks after Harvey, hurricanes Irma and Maria moved through the Caribbean as destructive Category 5 storms that engulfed many of the islands they passed over. As satellite images from NASA show, the winds of Irma tore the leaves off trees, turning the green landscapes of the Virgin Islands brown. As a result of Maria, the island nation of Dominica was decimated, and the entire electric grid in Puerto Rico lost power. Without running water, many Puerto Ricans are collecting water from brooks, springs, and streams.

The intensity of this year’s hurricane season has shown the immediacy of climate change. Previous predictions of extreme events have become a present reality: In just a few weeks, the Americas experienced rapidly intensifying storms, frightening winds, and record-breaking rainfall. Climate change “does not, by itself, cause hurricanes,” wrote meteorologist Tom Di Liberto for Climate.gov in September, “but it can certainly make a hurricane’s impacts worse.” As climate scientists explain, warmer seas and air affect the strength and intensity of storms.

Yet as Irma was headed toward Florida in September, the Environmental Protection Agency’s Administrator Scott Pruitt was not interested in discussing links between hurricanes and climate change. Pruitt, who has worked to roll back U.S. climate regulations, told CNN that such conversations were “very, very insensitive.”

Pruitt’s comments suggested that paying attention to climate change would eclipse vital human needs. But in an era when climate change is affecting people’s daily lives, these are not opposing concerns.

As Joe Evans, a Republican from Texas, said after he witnessed the widespread damage from Harvey, people whose homes were destroyed “probably don’t want to hear about climate change, but I guarantee in the back of their mind they think about it.” Evans recalled that he had similar thoughts: “I said, ‘I wonder what we’re doing to this planet to make it spiral out of control?’”

Hurricanes remind us of the impacts of human actions and industrial development, even while the timing and trajectory of storms reveal the limits of human control.

The devastation in Houston from a potent combination of toxic chemical plants, expanding urban development, and Harvey’s slow-moving path illustrates what many anthropologists have argued: Natural disasters are intimately social. Hurricanes, for example, are social because human actions have shaped the landscapes these storms flood and uproot. They are social because imbalances of power and resources influence governments’ priorities during disaster response and citizens’ abilities to access emergency assistance.

And hurricanes are social because oceans and air are warming as a result of human activity—which is making storms stronger. While national decisions about carbon emissions will affect hurricanes in the future, climate change is already affecting storms like Harvey in the present. To understand the potential social consequences of these damaging storms, we need only look to the past.

What we’ve learned from prior storms is that disaster “recovery” often does not help those who are most in need. According to environmental anthropologists Michael R. Dove and Carol Carpenter, scholars have found that “elites are consistently able to take advantage of” disasters “to further strengthen their positions at the expense of the marginal groups.”

Anthropologist Matilde Córdoba Azcárate and her colleagues describe this tendency in a 2014 article in the journal City & Society. They found that after two hurricanes in Cancún, government officials and investors directed resources to all-inclusive hotels and then to time-shares. These developments led to greater divisions between Cancún City, where Mexican residents live, and the tourist areas of the Hotel Zone.

“Before [Hurricane] Gilbert, tourists would come to the city for a walk, to dine at restaurants, to buy souvenirs at the markets,” one resident told the authors. But once all-inclusive resorts were built, many tourists saw little reason to explore beyond their perimeter. “Hotels, real estate investors, and public officials transformed the encumbrances of destruction into an opportunity,” Córdoba Azcárate and her co-authors found.

As communities struggle to recover from this season’s hurricanes, anthropologists predict that social inequalities will persist. “If history is any indication,” emergency resources that will be provided to Puerto Rico in the wake of Maria “will do little to alleviate long-standing disparities,” wrote Yarimar Bonilla, who conducts fieldwork in the Caribbean.

Likewise, after Hurricane Katrina hit the U.S. mainland in 2005, anthropologist John S. Petterson and his colleagues found that “national resources and funds intended for broad-scale ‘recovery’” actually led to a “further concentration of wealth.” Uneven recovery after hurricanes has only deepened inequalities based on race and class.

As climate change is fueling the conditions that make some hurricanes more destructive, storms lay bare social disparities. They show how quickly interconnection can become disconnection, as electric grids can be undone in a few short hours or days of wind—but, in some places, take months to rebuild. And they churn through regions without regard for political borders, even while economic and political conditions strongly influence recovery.

In the future, those lavender areas on the map may become more commonplace as storms intensify. Yet even as climate change is altering maps and human experiences, we can learn from the past as we rebuild in preparation for the future.

Communities throughout the Americas will be living with the aftermath of this year’s hurricanes for years to come. In Puerto Rico, developers have raised the possibility of expanding renewable energy. Flooding in Texas led to questions about past urban expansion into Houston’s wetlands, while Florida residents have wondered how likely it is that low-lying coastal areas will flood again, and how soon. Cities in Florida are making plans to increase the height of seawalls to prepare for sea level rise, while some people have argued that homes in the Florida Keys should not be rebuilt after they were devastated by Irma.

As communities slowly recover—and as we plan for more and more powerful storms—whose lives will change for the better and whose lives will become worse? Anthropological research suggests that some companies and government officials will continue to see storms as opportunities for development. But the new “opportunities” created by storms can conceal human suffering. Amid the destruction of hurricanes, some future possibilities are created while others are foreclosed.