Why White Kids Need Hamilton More Than Ever

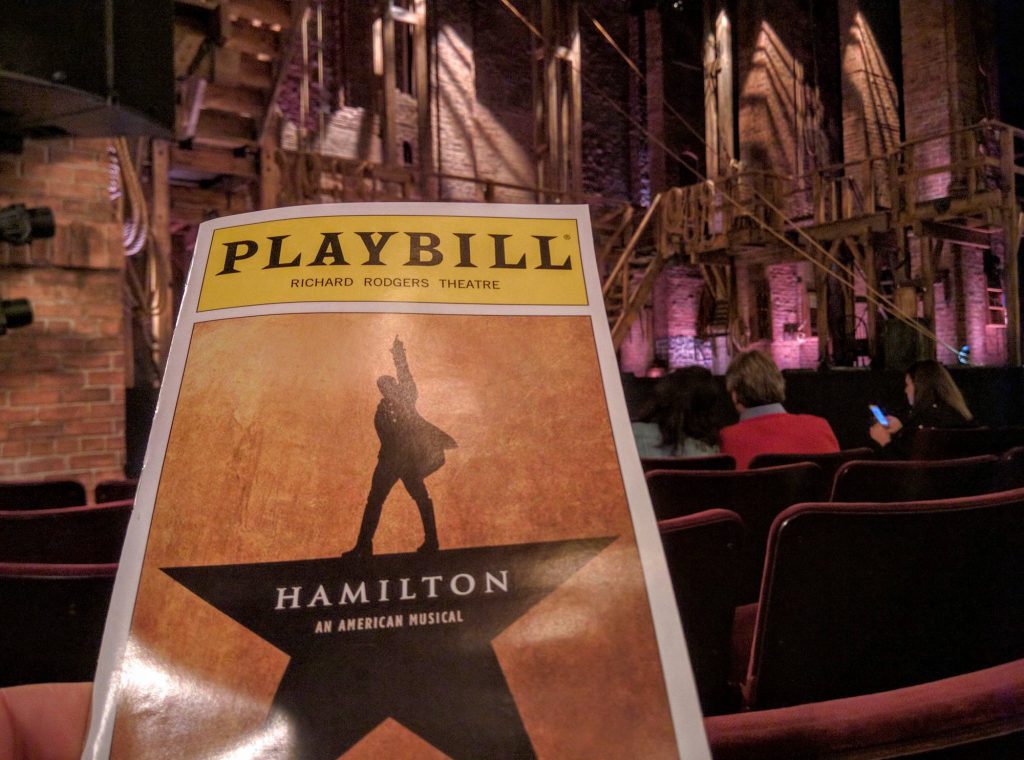

Every morning when my son opens the dishwasher for his morning chores, his daily tribute to the Broadway musical Hamilton begins in song: “How does a bastard, orphan, son of a whore and a Scotsman …” Our family will remember 2020 for three things: the COVID-19 pandemic, the intolerable killing of African American George Floyd at the hands of police, and Hamilton. My two White teenagers have memorized nearly every word of the musical, and they are not unique among their peers.

I’m not complaining. The musical, which retells the familiar story of the life of American Founding Father Alexander Hamilton with a cast of strikingly racially diverse actors, does a lot to break down damaging ideas about race. At the very least, the musical’s broad representation of people of color uproots mainstream messages in historically White societies about who’s capable of what. Hamilton goes well beyond the Hollywood trick of slapping characters of color into stories told by and for White people; it is told by and for a much wider audience. The show trains my kids to appreciate hip-hop and other predominantly Black cultural elements, sparking conversations about how to move beyond cultural appropriation to appreciating contextualized calls for racial justice.

In short, the narrative of Hamilton trains White kids to engage with people of color not with pity or disdain but by coming alongside as learners and co-conspirators.

There’s something else interesting underlying the musical that’s perhaps harder to put a finger on. As an anthropologist who has studied the ways people facing some of the world’s starkest racialized discrimination handle unemployment, I notice it. The story seems at first glance to present the usual American narrative that hard work is all that’s needed to go from rags to riches. But on closer inspection, it is clear that these characters understand their lives as more than hard work. They need to fight and struggle to rise up against their circumstances. They need to hustle.

In 2020, as many White Americans wake up to the reality that humans are neither invincible nor handed equal odds, the online release of the movie version of Hamilton this July couldn’t come at a better time. Privileged White kids growing up in America today, in particular, need to learn who has hustled and why so they can better understand their own entitlement.

As the son of Puerto Rican parents, raised in New York City, the show’s creator and star Lin-Manuel Miranda shares in common with his protagonist a journey from lower-class Caribbean obscurity to New York American fame. In the Hamilton story, people fight seemingly insurmountable problems, from inequitable education access to political power struggles. Miranda offers an account of this nation’s founding where odds and opportunities aren’t all equal, change won’t happen without a fight, and there’s no guarantee the heroes won’t get shot in the end.

Social theorists Cheryl Mattingly, Jerome Bruner, and others have emphasized that humans make sense of their world not just through static facts and ideologies, but through narratives. Among the most influential narratives are those that tell us how people can and should achieve the good life. Parents, schools, worship communities, friends, art, advertising, and media all pass along messages about how to make life good.

And here’s the thing: The many narratives that different people are exposed to do not all agree. The view of life as being unequal and unfair is one that my own middle-class White upbringing didn’t teach me to appreciate, for example. This disparity in stories is central to much strife, from anxiety to racism to war.

At a societal level, people who control narratives control power. Political rhetoric involves masterful narrative-shaping because voters don’t just choose a candidate, they choose a narrative. Likewise, systemic racism isn’t just about people believing isolated lies, it’s about believing and reenacting entire narratives that promote and justify White superiority. Most of these narratives are so subtle or ingrained that many people don’t think to name them.

Miranda himself recognizes the power of narratives. As the closing song of the musical reminds us, it matters “who lives, who dies, who tells your story.”

What’s so revolutionary about Hamilton’s narrative? The famous opening sentence frames it: “How does a bastard, orphan, son of a whore and a Scotsman, dropped in the middle of a forgotten spot in the Caribbean by providence, impoverished in squalor, grow up to be a hero and a scholar?” The answer, as the musical narrates, is “by working a lot harder, by being a lot smarter, by being a self-starter.”

On the surface, that sounds a lot like the narrative found in many history books: the rags-to-riches, bootstraps-pulling American dream story that scholars refer to as the neoliberal metanarrative. At its core is this: If you decide to work super hard, you attain wealth and glory. If not, you lose. This “try harder” narrative isn’t just an innocent way to teach children grit, it’s a story that dishes out winners and losers, and interprets the results.

Privileged White kids are steeped in it. As sociologist Margaret Hagerman writes in White Kids, the American Dream narrative of meritocracy is a means to “justify the superior position of the wealthy by claiming that the rich worked harder than everyone else and therefore deserve their privilege and the social rewards that accompany it.” By adulthood, it’s a go-to explanation to dismiss the racial disparities that come of hardships like pandemics or unemployment.

In her book about unemployed white-collar workers, American studies scholar Carrie Lane shows that rather than question overarching systems that cause layoffs, many American workers believe they can overcome unemployment by becoming “entrepreneurial agents engaged in the constant labor of defining, improving, and marketing ‘the brand called you.’” Many White kids grow up believing that it’s their merit alone that allows them to climb corporate ladders, from kindergarten to CEO.

That narrative has tugged and punched Americans along for a long time, but the cracks have long been spreading. Even while the U.S. hit record low unemployment rates in the 2010s, Americans were becoming less likely to find jobs that they found satisfying. Then enter the events of 2020: pandemic, recession, and Floyd’s tragic death—among other unjust killings of people of color.

As families try to make sense of millions of qualified individuals filing for unemployment each week (alongside the specter of millions dying from a disease without a cure) plus video footage of a man having his life squeezed out for seemingly no reason other than his killer finding his Blackness threatening, it feels ludicrous to tell children that hardworking individuals always rise to the top.

Americans can’t keep promising young people that they can go to college, work hard, and live a long, happy life. Nor can anyone keep pretending that median household net worths in the U.S. are 10 times higher among White than Black households because Black people are lazier. The hard work narrative is not working. It’s a myth.

The Hamilton script recognizes this. The next sentence in the musical’s opening summary of Hamilton’s life says that “the brother was ready to beg, steal, borrow, or barter.”

There’s an element of solidarity in this story—this individual is not just struggling alone, he is struggling within a group. In the word “brother,” it’s implied that that this group has been brought together by the same discrimination, disenfranchisement, inequity, and fight to rise above. Hamilton isn’t a lone ranger, he’s “another immigrant comin’ up from the bottom.” The path to the good life isn’t about one person making it at the expense of others; it’s about making it for and with your people.

There’s something else noteworthy in the opening phrase—the -er suffix. Hamilton wasn’t just working hard and smart; he was working harder, smarter. Than whom? The implied answer is than the people with more privileges than he’ll never have. In the musical, Hamilton’s struggles as a lower-class immigrant are portrayed as relatable to people marginalized by class, citizenship, race, or ethnicity today.

The hard work narrative is not working. It’s a myth.

In the famous words passed down across generations of Black Americans, “You’ll have to work twice as hard to get half as far.” Racism is real, and so is classism, sexism, ableism, and heterosexism.

The narrative in Hamilton takes the neoliberal narrative and fires it back at itself, saying: We’ve been told to work hard and then been denied the fruits of our labor, but watch us fight together in our way and get there anyway. In her study of working-class people of color in New York City, anthropologist Katherine Newman explains that Black youth adopt “an intensified version” of the American middle- and upper-class fixation on hard work because “forces of inequality, racism, and birthright have interfered with pure merit.”

This try harder narrative shows up all around the world where people face discrimination and obstacles at a societal scale.

For much of my children’s life, we lived in South Africa, where I studied South African responses to unemployment, described in my forthcoming book The Laziness Myth (due to be released December 2020). South Africa ranks among the highest in the world for unemployment, inequality, and entrenched racism. In 2020, amid pandemic unemployment, a recession, and a jolting national awareness of racial injustice, America has a lot in common with the South African situation.

In my research, Black South Africans often described their path to the good life as “hustling.” As one young man explained, a hustler “tries to make change for a living” and “keeps up the struggle.” Hustling means being, like Hamilton, “young, scrappy, and hungry” and never throwing away a shot. Hustlers are more creative, more subversive, less likely to take the system for granted, and more willing to rip it open at the cracks. Hustlers can spot when “there will be a revolution in this century,” and they respond with Hamilton, “Enter: me!”

Hustling also means learning to face death, a skill dominant culture doesn’t teach most privileged White kids. Many Americans freeze in terror of COVID-19 in part because they have accepted the modern biomedical narratives promising that technology makes them invincible. Hamilton’s narrative is honest: “Death doesn’t discriminate between the sinners and the saints.” With Hamilton’s awareness that “where I come from,” some don’t “live past 20” comes a readiness to “make this moment last” and “gladly join the fight.”

The musical’s plot turns on the tension between Hamilton’s scrappy hustler narrative and Burr’s preference to “wait for it.” Mid-musical, Burr’s transformation begins when he realizes that he’s “got to be in the room where it happens.” In the next scene, he’s openly campaigning, “chasing what I want.”

Burr admits to Hamilton, “I learned that from you.”

Shifting from waiting to chasing is central to Black Lives Matter and other civil rights movements. Malcom X’s motto, “by any means necessary,” was a call to chase after justice. Likewise, Martin Luther King Jr., from a jail in Birmingham, Alabama, chastised White people for their waiting narrative. He penned, “Freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed.” Like Burr, listeners might well learn from Hamilton’s chase-after-it drive.

No single work of art, even if kids memorize its every word, is going to override a lifetime of comprehensive racial learning. As Hagerman notes in White Kids, the foundation of kids’ racial understanding is often set through their parents’ “bundled” decisions like school, neighborhood, and extracurricular activities. As this year throws more hardships at American society than many of us have any idea how to handle, we should think consciously about the narratives we’ll use to guide children.

As children come of age in America 2020, White families would be wise to look to narratives told among those who have long been aware of the unequal playing field of systemic injustice and those who never took for granted easy employment or a long life. They need to regard Hamilton not just as a night of entertainment, a cultural curiosity, or a display of genius. It is a guidebook to join alongside the creative energy of hustlers, immigrants, and all those ready to “get the job done.”