Haiti’s Blackouts Are Both Electrical and Emotional

For the past seven weeks, Haiti has been brought to a standstill by almost daily protests and a months-long energy crisis that has led to gas rationing, fuel shortages, and rolling blackouts. The majority of schools, hospitals, markets, stores, and gas stations are closed. With no gas, most streets are empty, except for burning barricades and protestors facing off against police in occasionally deadly clashes.

The protestors are railing against the high cost of living in a country where more than half the population lives on less than US$2.41 a day. They are calling for an end to rampant corruption and the removal of President Jovenel Moïse, who, ironically, campaigned in 2017 on a promise to bring 24/7 electricity to the nation.

Energy has long been a pressing matter in Haiti. The country has some of the highest energy costs in the world. It also has one of the lowest rates of access to energy. Of the 9 million people in the Caribbean who lack electricity, more than 7 million live in Haiti. This chronic situation has been compounded by an acute one: A budgetary crisis, coupled with the end of Venezuela’s subsidized fuel plan in the region, has left the Haitian government unable to pay its energy bills.

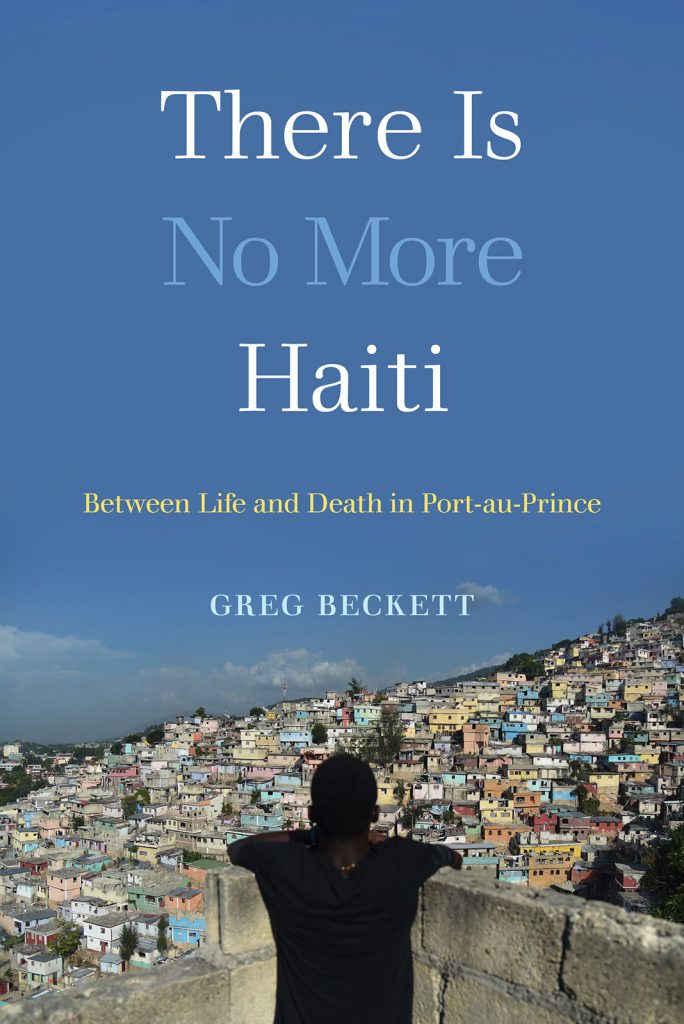

The situation is dire but far from exceptional in Haiti, where a decades-long political crisis has made it nearly impossible for many people to chache lavi—“look for life.” As an anthropologist who has worked in Haiti for more than 15 years, I explore the ways people struggle to live with and make sense of this long crisis in my new book There Is No More Haiti: Between Life and Death in Port-au-Prince.

One of the most striking concepts I have encountered is the Haitian Creole term blakawout, or “blackout.” In the past decade or so, Haitians have come to use this term as a potent image of both the lack of basic services in urban neighborhoods and the lack of a sense of security, agency, or power to shape one’s life.

One Haitian I know who used the term blakawout to describe his life is Vincent. [1] [1] Pseudonyms have been used to protect people’s privacy. When I first met him in 2002, he was an aspiring herbalist involved in a community group working to make a botanic garden in Martissant, a sprawling slum on the southwest edge of the capital, Port-au-Prince. I was struck then by his persistent joyfulness, even in the face of obvious difficulties.

But after a 2004 coup removed then-President Jean-Bertrand Aristide from power (for the second time), Haiti was flooded with a wave of violence, murder, and sexual assault by armed actors of various kinds—including gangs, the national police, and U.N. peacekeepers. Like many locals, Vincent and his neighbor Laurent* fled their homes and went into hiding in a different part of the city. After they left, someone set fire to a block of houses and destroyed Vincent’s home.

Being displaced, hiding, and losing his home and garden were particularly hard on Vincent, who had lived in Martissant all his life and had a deep relationship with the area and its community. In addition, he became very sick, suffering from persistent coughing fits and looking skinny and frail. But he had no money to buy medicine.

What follows is an excerpt† from my book describing conversations with Vincent and Laurent that took place in 2006. Their experience of “living in a blackout” offers a window into deeper cultural sensibilities that are highly relevant to the electrical and psychological blackouts of Haiti today.

“I feel weak all over,” Vincent said. “I can’t do anything. When there is a blackout in the city, you can’t do anything. For me, now, for us, we are living in a blackout [blakawout]. This is the worst time. Things in Haiti are very bad. We cannot live.”

Today’s crisis feels like a blackout, darkened by a sense of powerlessness, stuckness, and loss of agency.

Hunger, illness, poverty, misery, insecurity, and violence. They were everyday occurrences for Vincent and Laurent, as for so many others in the city. This is how crisis felt. Intimate. Like something that was happening to you. It felt like not being able to live.

I didn’t stay long. Vincent needed to rest, and I needed to get back across the city before the sun set. Laurent walked with me back downtown. As we walked, he told me that after the coup there had been violence every day, that everyone was in a state of constant shock. It made you tense, he said. He said that that was what Vincent had meant when he said they were living in a blackout. You knew it was coming, but you never knew when it was coming.

I listened as Laurent described his childhood in Martissant, before the coup. His father had once paid a man to hook up their house to the electrical grid. Such connections were illegal and dangerous. The people you paid to do it were experts; they knew what they were doing. Laurent said a neighbor, balking at the price for a connection, had tried to do it himself and had been shocked and badly injured.

In Haiti, chòk, or “electrical shocks,” are not the same as other kinds of shocks, the ones called sezisman or kriz (crisis). The latter are brought on by extreme emotional states, like grief or trauma. Such shocks touch you directly, they make you dizzy and weak, they make you collapse. They might make your whole body seize up. You might go rigid and then lose all energy and collapse. You might black out.

The anthropologist Paul Brodwin, in his discussion of illness categories in Haiti, says that sezisman and kriz are “unmediated bodily responses to loss” that leave your body weakened and prone to illness or even to sudden death. But they aren’t quite unmediated, even if they feel immediate and direct. Bodily responses to shock are mediated by culture and experience.

In Haiti, a person is composed of different parts. There is the body, of course, but it is only a temporary home for the soul, which has three parts. During life, when a part of the soul is weakened, the animating forces that make a person capable of acting in the world are reduced. Their blood goes bad or slows down. They grow sick and lose power.

Perhaps Vincent had all of this in mind when he spoke of the blackout. He was, after all, quite sick himself. And he was trained as an herbalist or leaf doctor; he had an intimate knowledge of health and illness, of the underlying theories of the body and the self. Whether he was conscious of it or not, his account of living in a blackout made it seem like the blackout was a kind of illness—a generalized lack of power caused by an inability to act autonomously in the world.

As I dwelt on his comment, I came to understand Vincent’s use of the image of the blackout as a phenomenology of political crisis, one that grounds the experience of the collapse of the state, the coup and the violence, and the everyday disruptions of what Haitians call ensekirite, or “insecurity,” in the bodily sensation of a loss of power and a loss of consciousness.

For Vincent and others like him, the violence after the coup came suddenly but certainly, and it created a shared sense of expectation and experience that shaped people’s lives in intimate and immediate ways. You couldn’t escape it because it was in your body, in your sense of self. Living in a blackout wasn’t just living with the lights off—it was living with the constant possibility of your own death.

Living in a blackout wasn’t just living with the lights off—it was living with the constant possibility of your own death.

The blackout means even more than this. It also brings to mind power in a general sense, the power to control one’s body, to do things in the world, to make value, to make things happen. For men like Vincent, men who were constantly looking for life, the blackout was a way of talking about their inability to find it.

Of course, Vincent was quite sick, and as his health deteriorated, his ability to work declined. But the loss of his home and his own displacement in the city were also part of what it meant to be living in a blackout. It was an unsettling condition in which you couldn’t do much of anything anymore.

This lack of capacity for action had a social sense as well. After the coup, talk of blackouts was also a coded way of talking about the loss of political power that had come with the removal of Aristide. The blackout was a concrete image that brought all of these things together at once. In Haitian oratorical practice, the blackout was a pwen (literally, “point”)—a mode of public commentary that, as anthropologist Karen McCarthy Brown described it, “signifies the essence or pith of a complex situation.”

Talk of blackouts is partly talk of the lack of something—a lack of services, of a responsible government, or of wealth to power one’s own private generators. To live in a blackout, though, was something more than a lack; it was an existential condition, a way of being in the world. And in this sense, talk of blackouts was always a way of commenting on matters of life and death, on the experience of a life shrouded in the possibility of its opposite, on the ever-present fact of darkness.

A blackout is how crisis feels when it happens to you. It is concrete and abstract, acute and chronic, anticipated and sudden. It is an individual and a shared experience. Like the Haitian concept of ensekirite for insecurity, the blakawout is both a disruption in routine and a disruption that has become routine. It is a kind of ontological insecurity in which people lose autonomy and control over the practices that anchor social life. And like ensekirite, people feel this loss of autonomy as a kind of sickness—a shock to their sense of self and to their emotional, physical, and bodily integrity.

In Haiti today, it seems the whole country is living in a blackout—literally and figuratively. The daily blackouts and roadblocks that have shut down Port-au-Prince and other areas are a potent reminder of the government’s inability to address the most pressing needs of its citizens. The energy crisis is like a blackout writ large, extended beyond the electrical grid to the country as a whole.

The situation is most acute in Port-au-Prince, where the electrical grid is predominantly located. Most of the country does not have electrical power aside from generators, but with no imported fuel, the generators are empty. Other towns and cities are also experiencing closures, blackouts, and protests.

When I read daily reports from friends in Port-au-Prince, I recall Vincent saying that when you live in a blackout “you can’t do anything.” To many people in Haiti, today’s crisis feels like a blackout, darkened by the sense of powerlessness, stuckness, and loss of agency that the word carries. I can’t think of more apt description for the political conditions Haitians must now navigate—conditions that have become, as many Haitians now put it, invivab (unlivable).

This excerpt has been edited slightly for style and length.