Do Guns Possess the Power to Change Us?

“Whoever touches that gun, he’ll die at some point … because it acts on you,” explained a 37-year-old man who lives in the poor neighborhood of Bel Air in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, where I have worked as an anthropologist since 2008. Kal was talking about a specific Smith & Wesson .38 special caliber revolver, long the standard issue gun of U.S. police and U.S.-trained security forces in Haiti. [1] [1] All names except the author’s have been changed to protect people’s privacy. After being purchased for US$75 from a former army soldier, this gun passed through the hands of three men: a young father, Frantz; Papapa, a young man; and Henri, another new father.

All three were shot and killed in their community between December 2012 and February 2013. Although the trant-uit (.38), as residents called the gun, did not fire all the lethal bullets, all died while in possession of it.

When I asked Belairians why these deaths occurred, they often surmised that the gunmen fell victim to maji, or “magic.” In Haiti, magic refers to an unethical use of spiritual power, distinct from ceremonial forms of Vodou, which call on ancestors to heal and protect the family. (Vodou is the preferred spelling, rather than Voodoo, which some practitioners view as derogatory.) This form of magic entails engaging with secret powers that allow a person to advance at the expense of another. To many, the men died because the occult forces they had been using for unethical gain had ultimately turned against them—opening them up to conflict and failing to protect them.

Yet when neighbors relayed how the deaths happened, they offered explanations involving a different kind of occult transformation: the supernatural potency of the .38 to change people into unethical agents. With each subsequent death, lore intensified around the gun, with people surmising that “touching” this gun could portend death. “Ever since they touched the gun, those poor young boys were not the same,” said one community member. Residents spoke about the gun as if it were an amulet that could change otherwise good people and what they did in the world.

It would be shortsighted to dismiss these claims as the misguided logic of a “superstitious people.” That racially inflected trope, long used to marginalize and demonize Haitians, among others, blinds observers to the way in which guns do exhibit a power akin to magic: the power to create a change in someone’s state of mind.

Taking seriously the supernatural effects of guns has broad relevance for understanding and addressing gun violence globally. In the United States, gun advocates tend to view the gun as a value-neutral tool. As they say, “Guns don’t kill people. People kill people.” On the other side are gun control advocates who argue that guns do indeed kill people: Without their lethal power easily at hand, as in other countries, far fewer deaths occur. But the anthropological lesson from Haiti is that the truth is more complex. It isn’t just the technological lethality of guns that makes them dangerous: They also exert a power on human agency. They change us. It is both the technology and the symbolism of a gun that can encourage someone to shoot.

Such power means that in contemporary urban Haiti, guns are both revered and reviled.

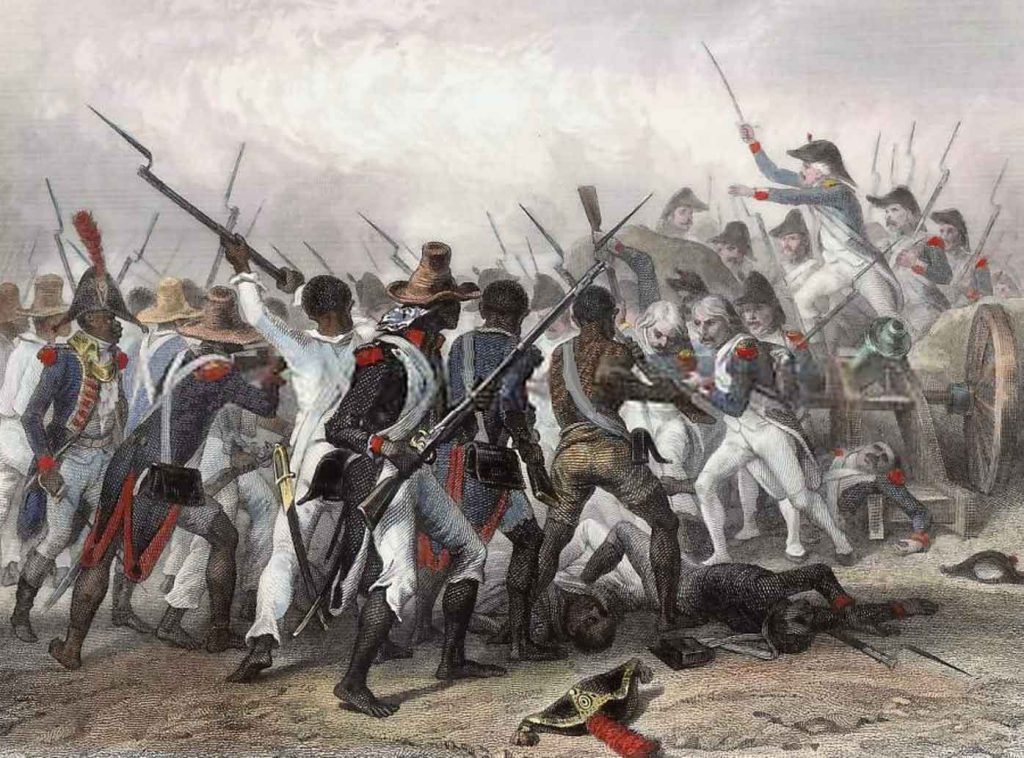

On one hand, gun possession stands for popular sovereignty. It was, after all, the courage of enslaved people to take up arms against a colonial power that secured Haiti’s independence in 1804. After the Haitian Revolution, generals distributed rifles to veterans as they transitioned to civilian life. For many years afterward, peasant armies were able to use their weapons to control regional territories and wage coups. As part of an effort to centralize power, the Duvalier family dictatorship, which lasted from 1957–1986, restricted gun ownership to the regime’s paramilitary network.

In an effort to shift power to the people in 1987, the democratic constitution adopted after the fall of the dictatorship granted citizens the right to armed self-defense. In a similar vein, the U.S. constitution, drafted on the heels of imperial rule and the War of Independence, enshrines the right to bear arms.

However, guns in Haiti, as elsewhere, can also symbolize the abuse of power. Although a general term for leader, the Haitian Creole chèf, when used in reference to an armed person, invokes the chèf seksyon (section chief)—the term formerly used for the dictatorship’s henchmen. Beyond a uniform and an ID card, it was the government-issued .38-caliber revolver that gave the chèf seksyon impunity to do anything in the name of their leader.

Today the term chèf is used both as an honorific for and a vituperation of the armed actors who protect the people and those that abuse them. These contradictory meanings are particularly at play when the term is applied to the heads of urban bazes—neighborhood organizations that have, since the fall of the dictatorship, taken on political and economic leadership of marginal urban zones. To wield a gun, and a .38 in particular, can signal a claim to urban chiefdom.

Residents foregrounded this symbolism in the story they told about the deaths of Frantz, Papapa, and Henri. As this story circulated and became standardized among neighbors, I began to understand it as less a factual account of what happened than a framing device for how to understand the pivotal role of the .38 in what occurred.

“You want to know the story of Henri’s death?” Kal asked me once. “It’s a story of three deaths, maybe more. OK, here is the story.”

According to Kal, it all started because baz leader Frantz brought his gun to his birthday party, a big affair thrown in the street, complete with a DJ. At the time, a rival baz led by Papapa was competing for control of the neighborhood, and the group made this clear by coming to the party uninvited and armed. Papapa was not happy to see that Frantz had his gun on him and was waving it in the air. “When they saw the .38, they wanted to ruin the party,” Kal told me. “Then Papapa shot at him. It happened quickly. Boom! He was lying on the ground. Everyone ran.”

“So now Papapa has the .38,” continued Kal. A few weeks later, Papapa and his friends went to another party hosted by a baz on a different block. Papapa’s group felt in control and at ease, drinking beer, dancing, and shooting into the air. A member of the host baz, Boss Henri, took offense to the brazen display and told Papapa that his guys can’t just come into their party and start shooting. Papapa saw things differently: “We’ll shoot if we want to. If the man has the .38, it’s shooting he’ll do.” To which Boss Henri responded, “If you keep shooting, I’m going to get my weapon.” When Henri confronted Papapa, it was, as Kal recalled, “bam bam bam!” Papapa was killed.

After the shooting, everyone ran—everyone except Henri, who found the .38 and claimed it. Kal surmised he did so because he knew that “that gun has a lot of power.” With the .38 in his hand, Henri began to act differently. To many, he appeared to have gone crazy with power, ordering people around, inciting fights, and even stealing from neighbors. As Kal told it, Henri was acting as anyone with a gun like that would. “You become a hothead. You feel force inside the body, and you think you can do anything. … He’ll go hustle. Rob people. … And the [police] guy finds him and fires many bullets.” And that’s how Henri met his end.

This is the story as it was told to me by Kal, and so it might not represent exactly how things happened or even how others saw it. But Kal’s story was also not unique. It aligned with the crime reports, and it resonated with what I heard from many others, most importantly in how they saw the role of the gun.

Although the gun had a potent effect on all three men, it did not act on them in the same way. For Frantz and Papapa, the gun enabled and epitomized their doomed claims to sovereign control of the block. For Henri, the gun pushed him into a trajectory of criminal action that could only have one outcome. Echoing Kal, Henri’s friend explained, “He saw the weapon, and he saw the road before him.” Yet another said, “Before, he was a nice young man. But the .38 showed him another way. He wanted to carry a bad name like Papapa.”

The gun in these accounts served not just as a tool that enabled preexisting intentions but as a catalyst for the development of previously inconceivable ones. The supernatural potency of the gun is its power to lay out new possibilities.

A gun is not just an inanimate object that can be separated from its user’s intentions. A gun held by a person is a human-technology composite that transforms what both can do in the world. As the philosopher and anthropologist Bruno Latour has argued, “You are another subject because you hold the gun; the gun is another object because it has entered into a relationship with you. … A bad guy becomes a worse guy; a silent gun becomes a fired gun.” The crux of this view is that people are needed to activate technology, and technology is necessary to activate and augment human capacities.

Yet Belairians’ accounts push this idea even further. Guns and people work together not only to fire a gun but also to imbue that technology with social meanings of power and violence. The potency of the .38 results from the way in which material objects and people must co-participate in creating lethal actors and actions in the world.

In the United States, the AR-15 assault rifle is the gun that has this power. It was an AR-15 that was used, sometimes with other weapons, to shoot and kill at a Pittsburgh synagogue; the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida; a Baptist church in Sutherland Springs, Texas; a concert in Las Vegas; and the Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, among others. The AR-15 is easy to use and extremely lethal, and, since the end of the assault rifle ban in 2004, abundant and accessible. Yet its availability and technology are only part of the story. It is also “America’s Rifle,” used by video game avatars and military heroes, in addition to mass shooters. It is an icon of popular entertainment and national defense—and now tragedy.

Frantz, Papapa, and Henri died untimely, unnecessary deaths, as did the 142 people (139 victims and 3 gunmen) in the five mass shootings listed above. There is a lesson to be gleaned from understanding the supernatural potency of guns. We cannot think about guns and people as separate entities, debating gun restrictions on one hand and mental health policy on the other. The target of intervention must be the gun-person composite. If we are to truly understand and control gun violence, we need to accept that guns have potent technological and psychological effects on people—effects that inspire violent ways of being and acting in the world.