For Families of Missing Loved Ones, Forensic Investigations Don’t Always Bring Closure

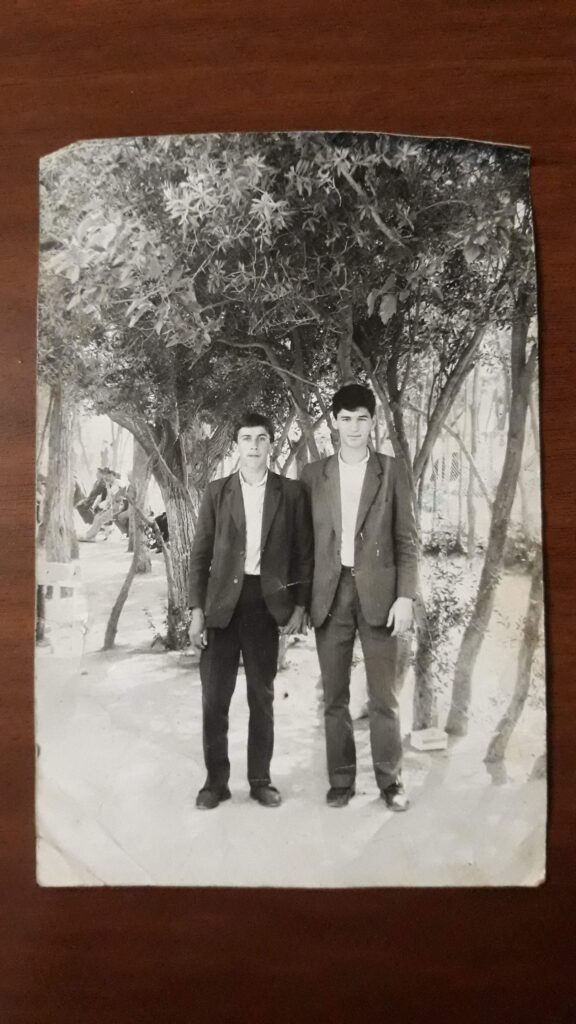

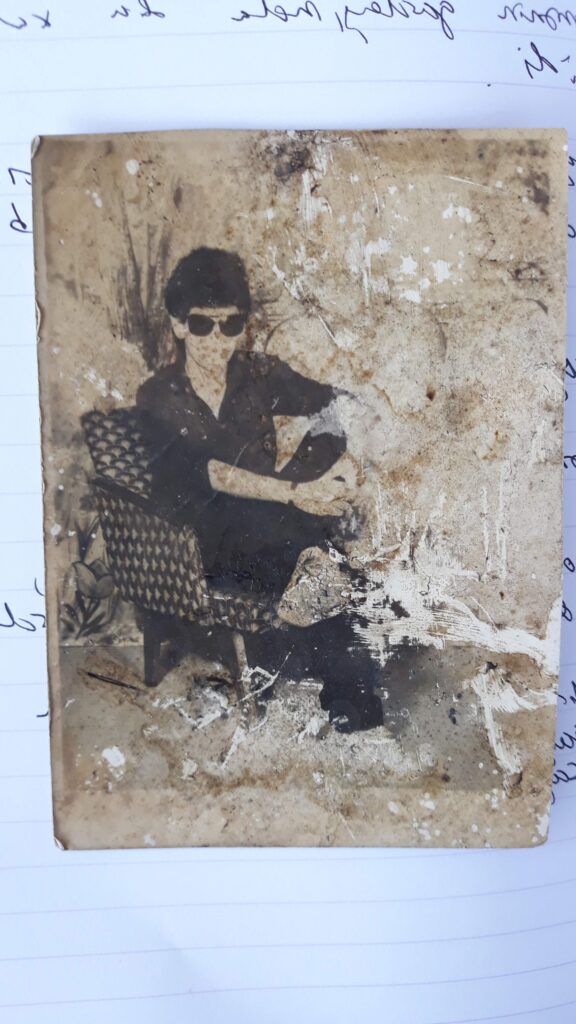

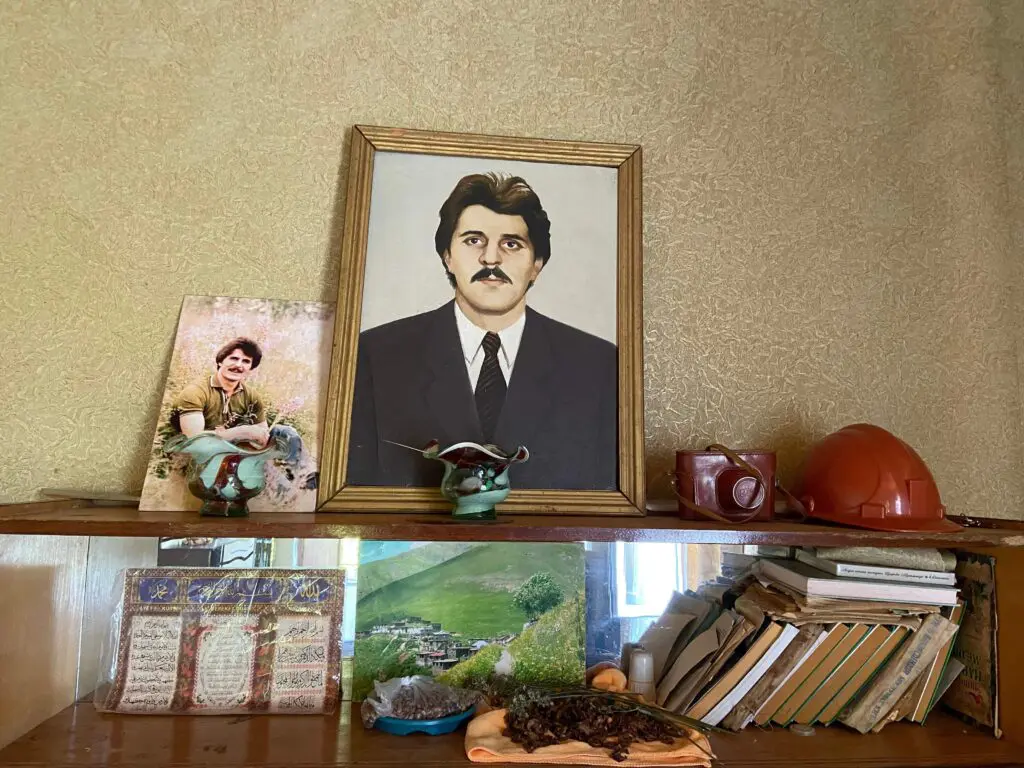

I first met Sarmaya—or Sarmaya Aunty as I called her—in the summer of 2020. [1] [1] Last names of interviewees have been left off to protect people’s identities. As we sat in her garden in a village in northern Azerbaijan, Sarmaya Aunty told me about her son Mahir, who disappeared during the First Nagorno-Karabakh War (1988–1994) between Armenia and Azerbaijan. After he disappeared, she visited a fortune teller named Malahat. Her son was alive, Malahat told her. He had married an Armenian woman and resided in Armenia with his family. Malahat even described Mahir’s appearance, including a scar on his forehead from a childhood accident. Since then, Sarmaya Aunty had held onto hope for her son’s return.

I saw Sarmaya Aunty for the last time in November 2022, when I asked her if she had received any news about her son. With the assistance of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), the government of Azerbaijan had just started the process of exhuming unmarked graves with the aim of identifying human remains. After nearly three decades of uncertainty, many hoped these forensic methods would bring clarity for loved ones of missing individuals.

Sarmaya Aunty shook her head no, then promptly added: “However, Malahat has told me that my son lives. He is not dead.” Her face lit up as she went on to recount the story once again. She passed away several weeks after our last meeting, amid ongoing exhumations in Azerbaijan.

According to ICRC offices in Azerbaijan and Armenia, around 3,890 people are registered as missing on the Azerbaijani side and around 400 individuals on the Armenian side from the First Nagorno-Karabakh War. Sarmaya Aunty was one of numerous relatives of missing people who I came to know as an ICRC humanitarian worker and later as an anthropologist.

Provisions for the respectful treatment, identification, and possible return of the remains of deceased individuals to their home countries during and after armed conflicts were first explicitly included in Article 17 of the First Geneva Convention in 1949. These have become central components of global humanitarian work. To meet international legal standards, the ICRC relies on forensic technologies and expertise when engaging with the gruesome consequences of conflicts, disasters, and migration.

For many, forensic science has come to be seen as the only path to truth and closure for families with missing persons. But forensics can’t always provide definitive answers.

For one, these methods require considerable time, money, and political will to implement. Forensic practitioners themselves admit that the majority of unaccounted remains can’t be recovered in a timely fashion or at all. In such situations, technological interventions risk compounding family members’ experiences of uncertainty by promising closure they cannot deliver on.

Beyond these practical limitations, forensic methods simply aren’t the only way to bring truth and healing to communities facing loss. Like Sarmaya Aunty, many people I met recounted their own experiences of fortunetelling, dreams, rumors, and bodily sensations that allowed them to make sense of their experiences. Rather than dismissing these methods, my research suggests humanitarian workers concerned with providing closure to communities should give weight to these stories and see them as what they are: effective coping strategies for dealing with traumatic and unresolved losses.

FORENSIC SCIENCE IN A CONFLICT ZONE

The ICRC has been at the forefront of efforts to clarify the fates of missing individuals in the aftermath of the First Nagorno-Karabakh War both in Azerbaijan and Armenia. From 2014 to 2022, the Azerbaijan office collected DNA samples from thousands of family members of missing persons. ICRC staff combines this data with medical records, personal histories, and any other relevant information they can gather to aid in the identification of human remains. They are now assisting the government in exhuming unmarked graves. As of May 2024, 73 individuals have been retrieved and identified before being returned to their families.

However, the forensic investigation has been slow, as I saw firsthand when I worked there from 2017 to 2019. The reasons for this require an understanding of the region’s history and the protracted nature of the conflict, including contestations over Nagorno-Karabakh.

Learn more about the author’s research on this episode of the SAPIENS podcast: “Why Do We Eat at Funerals?”

Azerbaijanis and Armenians coexisted side by side in the South Caucasus for many centuries, albeit not without interethnic tensions and territorial disputes. In 1920, the territories of present-day Armenia and Azerbaijan were taken over by the Soviet Union after a brief two-year period of independence from the Russian Empire. Their diverse populations were gradually subjected to Soviet policies that accentuated ethnic divisions. When the Soviet Union began crumbling in the late 1980s, conflicts between the two states bubbled over into the First Nagorno-Karabakh War. Both Armenian and Azerbaijani forces killed and forcibly displaced members of the opposite ethnicity from their territories.

In Nagorno-Karabakh and the surrounding seven districts between 1988 and 1994, up to 600,000 Azerbaijani citizens were forced out of their homes when Armenian forces took control of these territories. Three decades of diplomatic talks yielded no results. In 2020, Azerbaijan launched a full-scale military escalation that lasted 44 days, what became known as the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War, to regain control of these territories. Some displaced Azerbaijanis have since returned to these territories, though most cannot due to the dangers posed by unexploded ordnance from decades of conflict. This situation also stalls the ongoing exhumation process. Most of the graves with unidentified human remains are presumed to be located in Nagorno Karabakh and the formerly occupied seven districts.

In September 2023, tensions erupted again. Over 100,000 Armenians were compelled to flee their homes in Nagorno-Karabakh when Azerbaijan imposed a nine-month blockade on the territory, leading to a humanitarian crisis. After a 24-hour military offensive by the Azerbaijani military, the self-declared Republic of Artsakh in Nagorno-Karabakh surrendered and disbanded its armed forces. On January 1, 2024, the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic ceased to exist, and its territory was reintegrated under Azerbaijani control.

Armenia’s stance in this conflict has been driven by the principle of self-determination. Since Armenians constitute the majority in Nagorno-Karabakh, they contend the region should fall under their administration. Conversely, the Azerbaijani government asserts a sovereign right to defend Nagorno-Karabakh, which is internationally recognized as part of Azerbaijan.

However, both arguments are destructive and perpetuate exclusionary and divisive policies. The sides are still very far from finding a solution that benefits Azerbaijanis, Armenians, and the other ethnic groups inhabiting the region in an inclusive and mutually respectful manner.

NAVIGATING UNCERTAINTY

Communities living amid such long-standing and violent conflicts often reckon with questions over how, why, and when a loved one went missing. Scholars working in various parts of the world have documented both the strengths and limits of forensic science in providing closure in the face of these unknowns.

Some families may be reluctant to live through yet another period of uncertainty—years of not knowing whether forensic technology will be able to deliver on its promise of locating, exhuming, and identifying the remains of loved ones through a DNA match. This uncertainty is compounded when people receive only partial remains of those who are missing—a common result of forensic investigations—making it difficult to create a complete story of the loss.

At other times, as anthropologists have found, search teams and families may have various reasons for turning to other sources for support, particularly when the circumstances surrounding the losses are scientifically unverifiable or otherwise disputed. For example, Heonik Kwon documents how forensic teams searching for unmarked burial sites of missing soldiers from the Vietnam War have turned to dreams and spirit mediums for assistance. Similarly, Alexa Hagerty recounts how forensic scientists conducting exhumations in Guatemala couldn’t differentiate between the recovered bodies of two brothers killed by the military in a massacre. The family concluded through a dream, however, that the younger brother’s body had been found, leading to a funeral for him. In Uganda, Jaymelee Kim observes that the inability of forensic interventions to deliver on its promises have at times exacerbated psychological and spiritual distress among surviving kin in the aftermath of the Lord’s Resistance Army conflict.

In my research in Azerbaijan, I found that Sarmaya Aunty was not alone in looking beyond forensic methods to help navigate extreme uncertainty. One woman, Reyhan, repeatedly recounted to me a dream she had about her husband Salim, who also disappeared in the war in the 1990s. A year after his disappearance, Reyhan dreamed he had come home, and they were holding hands and speaking together. She felt his hand warm in hers. When she woke up, no one was there—but the hand he held in the dream was warm. “Since that day, I have lost hope,” she told me. “It means his soul came to visit me. Perhaps it was the day he died. At that moment, he perished.”

Reyhan’s dream about her missing husband shaped her understanding of his fate. She started referring to him as “my late husband.” The dream also offered her a mechanism to process complex emotions and meaningfully interpret her life experiences. Her feeling of certainty didn’t bring a definite resolution to her ambiguous situation, but it empowered her to take control of how she interpreted her life.

In the face of such profound uncertainty, whether one accepts the personal truths of Sarmaya Aunty or Reyhan is not the point; what matters is holding a space for meaningfully engaging with one’s loved ones.

BEYOND FORENSIC SCIENCE

All this does not suggest that forensic science should be disregarded. In some parts of the world, forensic exhumations have played and continue to play a significant role in documenting political atrocities and addressing human rights violations.

In Guatemala, for instance, such investigations have unearthed evidence of state-sponsored mass killings during the civil war, contributing to ongoing efforts for justice and reconciliation. Similarly, in Argentina, forensic efforts have been crucial in uncovering the truth about the “Dirty War” atrocities, although challenges remain in the pursuit of accountability. Recently, international bodies have rightly called for independent forensic investigations in Gaza, as evidence mounts of Israeli forces committing human rights violations and war crimes against Palestinians. In Ukraine, forensic efforts have increased to meet the current demands to identify missing people and document and prove war crimes, primarily by Russian forces.

Countless family members of missing persons with whom I have interacted in Azerbaijan also yearn to “have a site to mourn” for their missing loved ones, where they can receive their remains and lay them to rest. Forensic technologies can and do play a crucial role in making that happen. One woman told me, “I am so envious of those who can visit the graves [of their loved ones]. I have never been an envious person in life. I am only envious that I don’t have a grave to visit.”

But some families remain split on whether to pursue or put weight on forensic investigations.

In one family I know, a brother is actively searching for the remains of Vugar, his missing sibling. His sister, however, opposes the search and becomes distressed at television reports of newly uncovered unidentified skeletal remains. The brother had a dream in which Vugar asked, “Why are you searching for me in cemeteries?” The sister views this dream as evidence that she should maintain hope for his eventual safe return.

To best serve the nuanced needs of all those impacted by forced disappearances, humanitarian workers must go beyond a narrow focus on scientific truth and forensic technologies. They must recognize the value of incorporating personal histories, shared beliefs, and broader political circumstances into their work.

This holistic approach, which can be enhanced through the involvement of sociocultural anthropologists throughout all stages of humanitarian work, may enable more attuned forms of care for affected communities—and open the door to other ways of healing.