In 1925, Margaret Mead set sail for American Samoa. What she claimed in her book Coming of Age in Samoa to have found there—teenagers free to explore and express their sexuality—instantly captivated her audience in the U.S. Her book became a bestseller, and Mead skyrocketed to fame.

But what were her actual methods and motivations? We trace Mead’s legendary nine-month journey in the South Pacific.

See the companion teaching units,“Margaret Mead’s Ethnographic Work in Samoa” and “Margaret Mead’s Remarkable Career.”

This episode is included in Season 6 of the SAPIENS podcast, which was made possible by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Flapper of the South Seas

[introductory music]

Voice 1: What makes us human?

Voice 2: Who you are.

Voice 3: History

Voice 4: Your function in community. That’s where we find our purpose.

Voice 5: We are profoundly connected as human beings.

Voice 6: What makes us human?

Voice 7: Let’s find out.

Voice 8: SAPIENS.

Voice 9: A Podcast for Everything Human.

Kate Ellis: The year is 1928. Margaret Mead has just published Coming of Age in Samoa. The titillating cover of a topless couple grabs everyone’s imagination. Along with its romantic opening chapter, read here by an actress playing Mead.

Voice Actress: The life of the day begins at dawn. Or if the moon has shown until daylight, the shouts of the young men may be heard before dawn from the hillside, uneasy in the night. Populous with ghosts, they shout lustily to one another as they hasten with their work.

Kate: The book became an immediate bestseller. It was one of the first anthropology books for a general audience. And it catapulted Margaret Mead to international acclaim.

But before all that, before the fame, before her career as a public intellectual, before the controversy that would threaten to undermine everything Mead had made of herself, there was that first step she took onto the islands of American Samoa in the South Pacific.

For Mead, it was an incredible opportunity to conduct research on an Indigenous community that anthropologists had yet to touch.

Kate: This is The Problems With Coming of Age. I’m your host Kate Ellis. Today our episode is: “Flappers of the South Seas.”

[music]

Paul Shankman: It’s very interesting that Mead had never visited another culture before. She was only the second American woman to work overseas because virtually all anthropologists were working with Native Americans at the time.

Kate: Paul Shankman is an emeritus professor of anthropology at the University of Colorado, Boulder. He’s written two books about Margaret Mead, and he’s worked periodically in Samoa since the mid-1960s.

Mead was aware that she didn’t fit into the boxes that society had defined for her. But going to American Samoa gave her a place to study the lives of young girls not so unlike herself. And also a place to grow into herself as a thinker, a scientist, an observer of humanity.

Paul: Fieldwork was becoming the gold standard of cultural anthropology at that time. And she’d heard from her friends and colleagues about “their people.” And Mead wanted a people of her own.

Kate: In American Samoa, she would discover answers that would pique the interest of American audiences and give them an opportunity to contrast Samoan cultures and their own.

Specifically around becoming and being a teenager. Did adolescence always have to be so hard? Were the difficult transitions to being an adult just a natural part of being human or the result of culture? By going to the South Pacific, Mead could hold a mirror up to U.S. societal norms. Maybe, she wondered, there was another way to grow up.

[music]

Kate: Margaret Mead had never been west of the Mississippi. And getting to American Samoa was an undertaking. She took a train across the U.S., then traveled by ship from San Francisco to Hawaii. To complete the final leg of her journey, she traveled almost 2,600 miles across the Pacific to Pago Pago Harbor in American Samoa.

Mead made local headlines from Philadelphia all the way to Honolulu about her study of the Samoan people.

The media said she was going to study the “flappers of the South Seas,” that is, Samoan female adolescents, says Nancy Lutkehaus, an anthropology professor at the University of Southern California. And at one point an assistant to Mead.

Nancy Lutkehaus: If you think about what was going on in the 1920s when Mead went off to do her fieldwork. People didn’t understand the flapper generation. They didn’t understand, young women wanting to cut their hair, bob their hair, and smoke cigarettes. I mean, there were societal changes that were going on particularly among women’s roles, and it was starting among adolescent girls.

So there was a lot of conflict between the generations that was attributed to hormonal changes.

Kate: Back in May, we went to Samoa to walk in Margaret Mead’s footsteps. Chip Colwell, editor of SAPIENS, was part of that group. He began a few paces from where Mead would have disembarked her ship.

Chip Colwell: This is super cool to imagine Margaret Mead arriving in August of 1925 as a young anthropologist ready to begin her fieldwork. She needed a place to stay. And so, she came here to Sadie Thompson’s. Found a room right here on the first floor.

Kate: Chip stands in front of a blue and white building. A little worn around the edges and yet graceful.

Chip: With Samoan mats on the floor and furniture. She said she was really very comfortable there, and this was her home base as she settled in and began to imagine herself pursuing fieldwork here in Samoa.

So, she began to meet different people around the island, and she began to study Samoan, and her teacher was a nurse named P.F. Pepe, and she was a graduate of the Atauloma Girls Boarding School, run by the London Missionary Society.

Kate: With her work being centered around adolescence, when Mead heard about the school, it seemed like it could be an ideal field site for her. So, that’s where she went next. We did too.

We walked along a narrow trail overgrown with brush. Poet and novelist Sia Figiel led the group looking for Atauloma, now hidden somewhere in the rainforest.

Sia Figiel: We’re going up to Atauloma, the missionary girls school in American Samoa that was built at the, you know, the early turn of the century. And Margaret Mead used to visit it. She would come from Leone to go up there. It was a mainly Samoan speaking school for young girls. [out of breath] I cannot believe they made this trek! We’re going up a hill, and it’s very slippery.

Kate: In Mead’s time, it was one of two secondary schools on the island and the first to admit girls exclusively.

Sia: And it just makes me wonder why they would put such a school up here. I mean, so far away from the coast and from everyone. It probably speaks to the importance of these girls, that they were probably all chiefs’ daughters, and they needed to be sequestered, perhaps, you know?

Kate: Atauloma was a stronghold of Christianity, and Pago Pago was overrun with missionaries. Initially, these young girls were being trained to be pastors’ wives at this school and to embody strong Christian values.

It was a school of prestige, and the nuns here closely guarded these young women’s behavior, including their sexuality.

Before Christianity arrived in Samoa, young women, primarily daughters of high-ranking chiefs, were known as taupou. Often performing specific duties, the taupou carried the honor of their family and village. A vital part of this role was to remain a “ceremonial virgin” until marriage, which aligned very well with Christian principles when the first missionaries arrived in the 1830s. By the time Mead arrived nearly a century later, Christianity had become firmly entrenched.

The question of sexual freedom would become central to Mead’s research and the controversy that would later haunt it.

After an hour of searching, the team finally found it, inside a thicket of Samoan jungle, close to that slippery hill. Here’s Chip again.

Chip: We’re now standing in the amazing ruins of the Atauloma Girls School where the forest or bush or jungle is reclaiming this building. We’re standing in a long, open portico that maybe extends 200 feet one way and maybe 50 feet another, with really tall ceilings.

So, you have these vines that are crawling up the moldy walls and tearing them down. The ceiling is collapsing in different parts. The central rooms have been completely overtaken by thick vegetation. You can’t even walk into them, it’s so dense.

Kate: In September of 1925, Margaret Mead would have stood right here. Welcomed by a feast and a series of performances by the girls of the school.

But she was unimpressed. This wasn’t the Samoa she was looking for.

Chip: The girls had very little freedom. They were just being educated mostly in how to be good Christian girls, and they would have had very few freedoms, very few opportunities to live in traditional ways.

Kate: Mead was looking for a Samoa untouched by the West and Christianity.

She wanted to explore a culture she couldn’t find in the U.S. Something she and those in anthropology would have referred to as “primitive,” a term widely used in the field during her time but considered offensive and problematic now. And here’s Margaret Mead herself explaining.

Mead: The word “culture” in the anthropological sense was hardly known then. The new anthropological sense was that you studied the whole, shared, learned behavior of a group of people, and you called it “the culture.” The tools people used, and the lullabies they sang to their babies, the way they built houses and buried their dead, and their religious beliefs were all part of their culture.

Chip: She left here inspired to actually find a different field site. And so she went back to where she was staying and found Manu’a, where she decided that this was going to be the place she wanted to go to.

[music]

Kate: The Manu’a islands were exactly what she was looking for. They’re east of the main island of American Samoa. They were more isolated. Although there was some Christian influence, they retained more of the traditional ways of life that Mead wanted to study.

She stayed with a local family on the island of Ta’u. They ran the naval medical dispensary and were the only White family. One with local connections to Samoan families and teens.

From this network, Mead was determined to get what she was after—understanding how Samoans transitioned from childhood to adulthood. A portrait of Samoan adolescence. Paul Shankman again.

Paul: She lives in a room that opens on to three villages that are in close proximity. And she has access to a large sample of adolescent girls, and she both goes out into the villages to meet with people, but even better, they come to her back porch from early morning until late at night, and she’s seeing so many people so often.

Kate: These were the young girls she worked with to conduct her fieldwork. She wanted to know how these young girls became women. What their adolescence was like. In Coming of Age in Samoa, Mead wrote that she studied:

Voice actress: “Twenty-eight children who as yet showed no signs of puberty, 14 children who would probably mature within the next year, and 25 girls who had passed puberty within the last four years but were not yet classed by the community as adults.”

Mead gathered descriptions of their cultural practices through typical ethnographic methods—interviews, observations, extensive note taking, intelligence, and personality tests, and family trees. Nearly all this information was captured in Samoan, since according to Mead, only one American family spoke English on the island. By that point, she had a basic understanding of the language.

In her research, Mead described the importance of societal structures and hierarchies. Like high chiefs taking responsibility for the village’s well-being. And how men and women were separated by gender and age, and they had different roles, such as fishing or child-rearing.

She studied early childhood education, the different treatment of the sexes, and etiquette.

But the part of Mead’s research that would become the most controversial and electrifying to the American public was her descriptions of Samoan attitudes toward sex.

In her field notes, she described Samoans as nonmonogamous, and their sexual practices as casual and relaxed.

Of kids and teens, she wrote:

Voice actress: “They also have a vivid understanding of the nature of sex. There were only three little girls in my group who did not masturbate. Theoretically, it is discontinued at the beginning of heterosexual activity and only resumed in periods of enforced continence. Among grown boys and girls, casual homosexual practices also supplant it to a certain extent.”

“Familiarity with sex and the recognition of a need of a technique to deal with sex as an art, have produced a scheme of personal relations in which there are no neurotic pictures, no frigidity, no impotence.”

Kate: Mead wrote in Coming of Age in Samoa that her informants were honest in their discussions of sex and sexuality with her. Later, it became one of her talking points to the public in the West—that sex didn’t have to be a source of stress. Rather, it could be carefree and guilt-free. Without pressure.

After spending just over six months in Ta’u, Mead concluded that being a teenager in America was a turbulent time not because adolescence was simply “hard,” a universally difficult experience. But rather, it was due to the culture American teens were raised in, whereas Samoan culture was different. So not everyone’s experience of being a teen is the same. It depends, she argued, on where you grow up. It was largely not nature that defined you, but nurture that shaped who you became.

The take-home message to people in the U.S. was clear.

Paul: People could make choices about bringing up their kids. And this was an important general point for a popular audience. Biology was not destiny, so Americans could make better choices about bringing up their kids.

Mead proposed something called “education for choice.” The idea was to give young people a range of options around how they live their lives. To have the freedom of sexual experimentation. And to discuss puberty openly, without shame. Mead believed this approach would alleviate the stress and turmoil that seemed to define American adolescence.

That is—if only parents were less controlling, their children’s teen years would be far less turbulent.

When she returned to the U.S., Mead distilled her ideas on being an adolescent girl in Samoa into one of many National Research Council reports.

One report caught the attention of publisher William Morrow and Company. And they wanted Mead to turn it into a book for an American audience.

Paul: Mead and her publisher realized that adolescence was a popular concern in America. When Mead talked about “storm and stress,” American parents could relate because young Americans in the 1920s were experiencing a lot of problems including, quote, juvenile delinquency.

Mead agreed to expand her technical report. She wrote “A Day in Samoa,” an alluring opening chapter. And she wrote two additional concluding chapters that compared Samoan and American young people.

Paul: So people were looking for answers. And Mead provided those answers using Samoa. And she thought of Samoa as a positive counterpoint to America. So Samoan adolescence was less stressful, less full of conflict than America.

Kate: And that idea: It spread like wildfire.

[overlapping voices reading headlines]

Voice 1: “Samoa Is the Place for Women Where Neuroses Cease”

Voice 2: “Mead Is One of Anthropology’s Most Creative and Brilliant Personalities”

Voice 3: “Miss Mead’s Graphic Picture of Polynesian Free Love Is Convincing”

Kate: Coming of Age in Samoa was reviewed within a few years of its publication by Reader’s Digest, The New York Times Book Review, Vanity Fair, The Journal of Juvenile Delinquency, and more.

Mead’s depiction of “free love” within Samoan society was especially exciting in the U.S.

She wrote:

Voice actress: “Sex is a natural, pleasurable thing; the freedom with which it may be indulged in is limited by just one consideration: social status.”

“All of this means that casual sex relations carry no onus of strong attachment and casually broken without strong emotion.”

Paul: And this particular chapter in Coming of Age in Samoa was the focus of a great deal of attention, even though it’s only a small part of the actual book, but the American Legion at the time, for example, labeled Coming of Age in Samoa a “sex book,” and many people found it a little bit shocking, although it’s very tame by current standards.

Kate: There were many who responded positively.

Paul: Morrow had initiated a publicity campaign for the book. He sought endorsements from [anthropologist] Bronisław Malinowski and Havelock Ellis, noted sex researcher.

Kate: Coming of Age became a bestseller. And Margaret Mead rose to worldwide fame.

Paul: It put anthropology on the public radar, and Mead herself became a public figure.

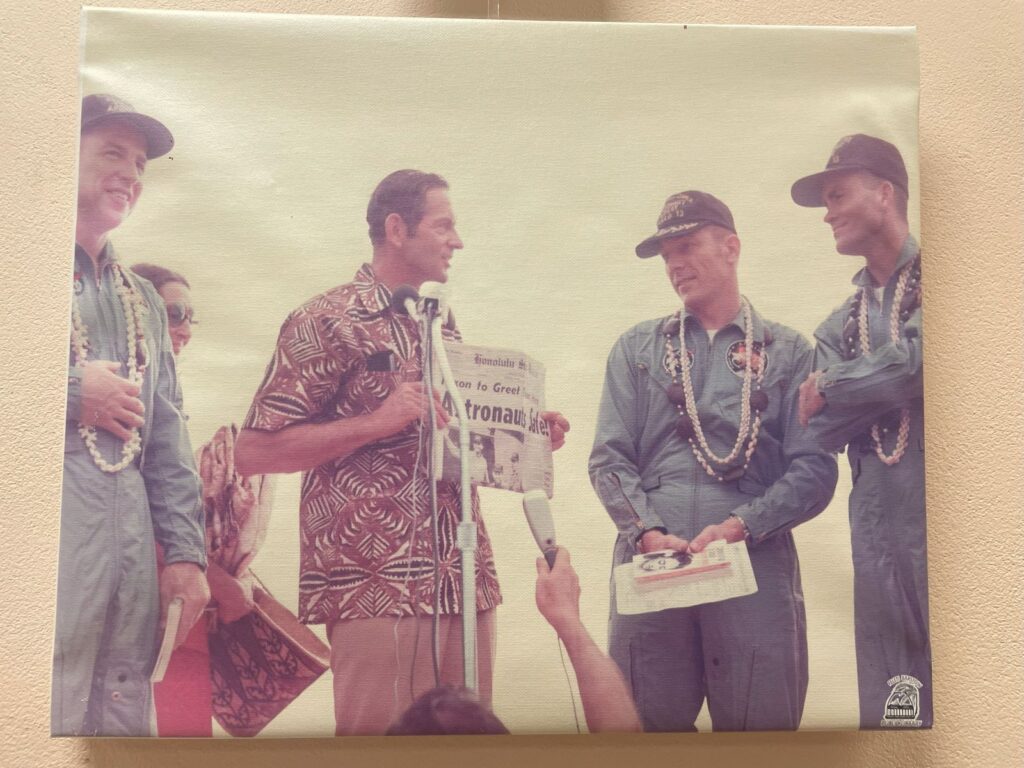

Kate: She was invited to give lectures all over the world, wrote hundreds of popular articles, and regularly appeared on TV. In the decades that followed, Mead’s work in Samoa shaped Dr. Spock’s influential philosophy on permissive childrearing, fueled the sexual revolution and Second Wave Feminism in the 1960s, and laid the foundation for her critique on race with the celebrated social critic and author James Baldwin. She received 28 honorary doctorates and the U.S. Presidential Medal of Freedom. One American astronaut coming back to Earth from space—who splashed down near the Samoan islands—even received her book as a welcome home present.

Coming of Age in Samoa and Mead’s research also stimulated a bigger debate within the social sciences and humanities—the idea of nature versus nurture. If adolescence was cultural, then what about race, intelligence, gender, sexual orientation, and so much more about the human experience?

This debate would echo throughout the academic world—and the public—for years to come, parts of which are relevant even up to this day. But in the midst of all this acclaim and attention, winds of discontent began to stir. Some were skeptical about the very foundations of Mead’s research, especially Samoans themselves.

Voice 1: I was affronted by the used of the word “primitive.”

Voice 2: Did that really happen? Or didn’t it happen? Who’s telling the truth here?

Voice 3: I think old Margaret got taken a little bit, yeah [laughing]. Poor lady. [laughing]

Kate: That’s next time, on “The Problems With Coming of Age.”

[music]

Kate: “The Problems With Coming of Age” is a co-production of SAPIENS and PRX Productions.

Be sure to check out the season’s college curriculum, historic photographs, and so much more on our website: SAPIENS.org/podcast.

Doris: This episode was written and produced by Rithu Jagannath, Ashraya Gupta, and Ari Daniel. This season was hosted by Kate Ellis and me, Doris Tulifau.

Kate: From SAPIENS, we were supported by Chip Colwell, Tanya Volentras, Esteban Gómez, Sia Figiel, Salamasina Figiel, Sophie Muro, and Christine Weeber. The season’s humanities advisers were: Danilyn Rutherford, Lisa Uperesa, Nancy Kates, David M. Lipset, Nancy Lutkehaus, Agustín Fuentes, Don Kulick, and Paul Shankman.

Doris: And fa‘afetai to the more than three dozen people we interviewed in American Samoa and Samoa for helping to shape our understanding of this story.

Kate: The executive producer of PRX Productions is Jocelyn Gonzales. The project manager of PRX Productions is Edwin Ochoa. The business manager is Morgan Church.

Doris: Dan Taulapapa McMullin created the season’s cover art. Celina T. Zhao was the fact checker.

Kate: Audio mastering by Terence Bernardo.

Doris: Music by APM, with additional tracks by Malō Fa’amausili recorded at Apaula Studio, as well as songs kindly provided by Bobby Alu.

Kate: Nancy Madden was our voice actor playing Margaret Mead.

SAPIENS is part of the American Anthropological Association Podcast Library.

Doris: SAPIENS is an editorially independent podcast funded by the Wenner-Gren Foundation, which has provided vital support. Our thanks to the foundation’s entire staff, board, and advisory council. Season 6 of the SAPIENS podcast was made possible by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

I’m Doris Tulifau.

Kate: I’m Kate Ellis.